What happens when you have a good idea, but it relies on other good ideas which haven’t been invented yet? You work around with the tech you do have. That’s what happened with the steam locomotive.

The steam locomotive first appears around 1802 or 1804 depending on your sources. It’s not too important which year is absolutely correct in the context of this topic. But what happened when it was test run is. Trevithick’s locomotive, although absolutely tiny by locomotive standards proved too heavy for the cast iron rails then in use. It crushed them under its wheels as it moved along. It couldn’t be made lighter, because then it wouldn’t be heavy enough to haul wagons behind it. It couldn’t be put on springs because there was no way to build springs strong enough for the weight of such a locomotive yet.

So engineers waited for improvements in iron and steel production, to make stronger wrought iron rails, and sturdy steel springs, and the concept of a locomotive was filed away for a couple of decades. Except that’s not what happened at all.

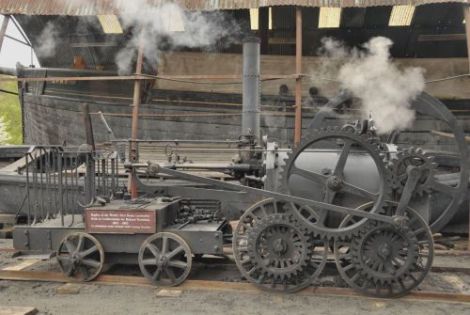

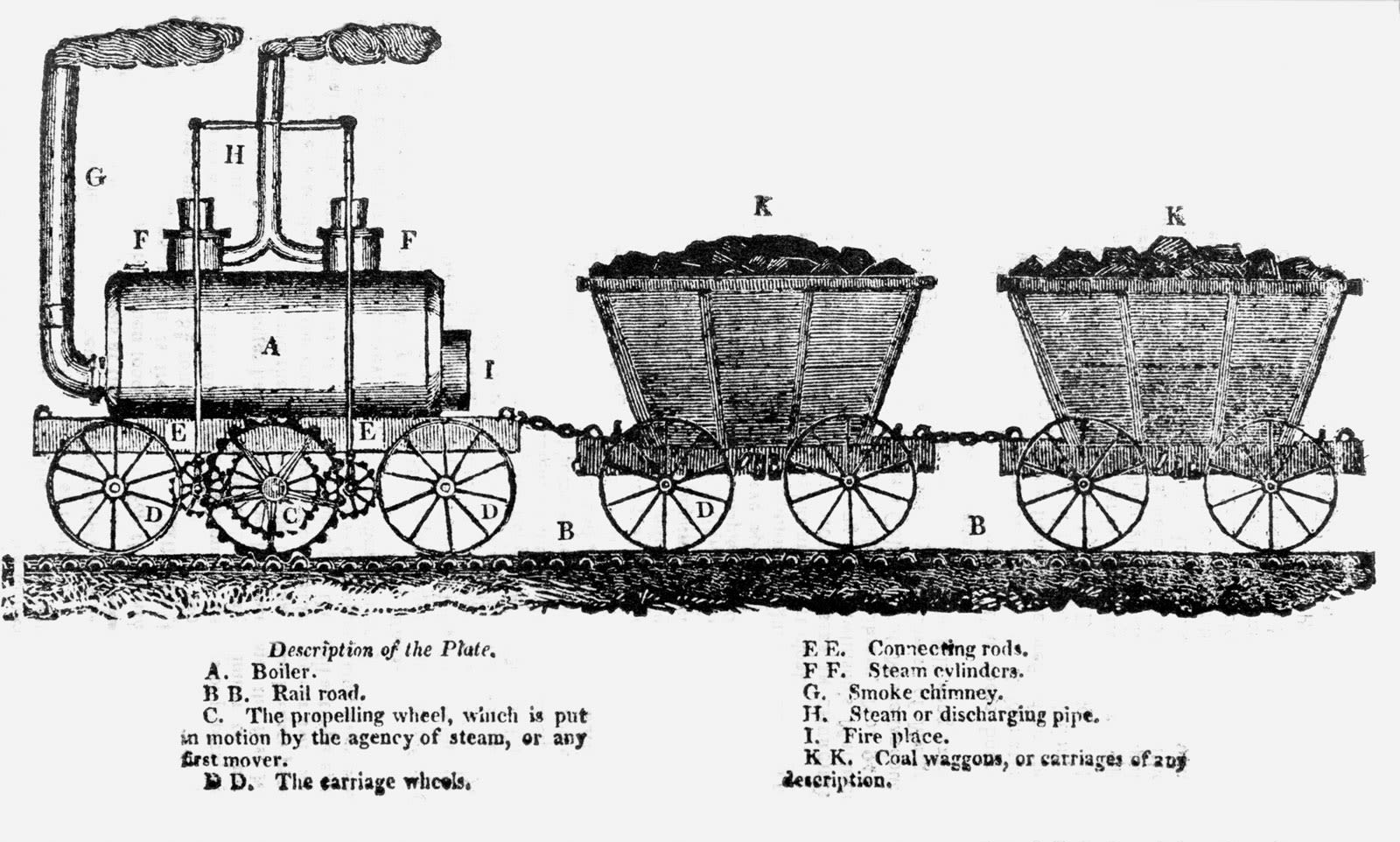

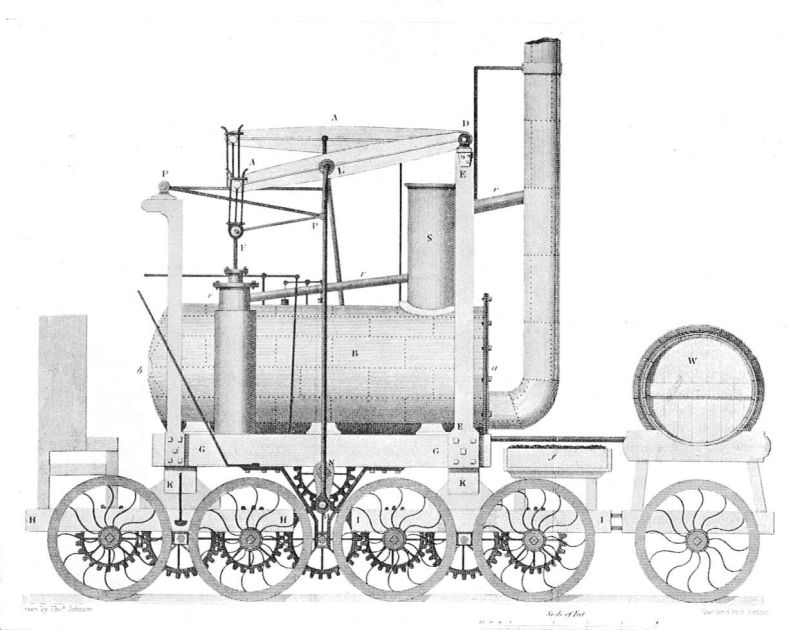

While the idea was shelved for a few years after Trevithick’s attempt, the Napoleonic wars raised the prices of horses and feed to the point that developing some sort of mechanical alternative became economically feasible. Blenkinsop came up with a solution for building a workable locomotive without the rails and springs that were needed to support the weight of a machine like Trevithick’s (or those of the 1820's and beyond). The locomotive had to be light weight so as not to break the cast iron rails. But it still had to pull tons of wagons, and lacked the necessary adhesion to do so now that it wasn’t as heavy. The solution was obvious to Blenkinsop: equip the rails with a rack, and the locomotive with a drive cog. The cog engaged the rack and pulled the train along the tracks. The wheels of the locomotive only had to provide support, not drive, so the machine could be much lighter. It was built into a substantial wooden frame that added some shock absorption without the use of springs.

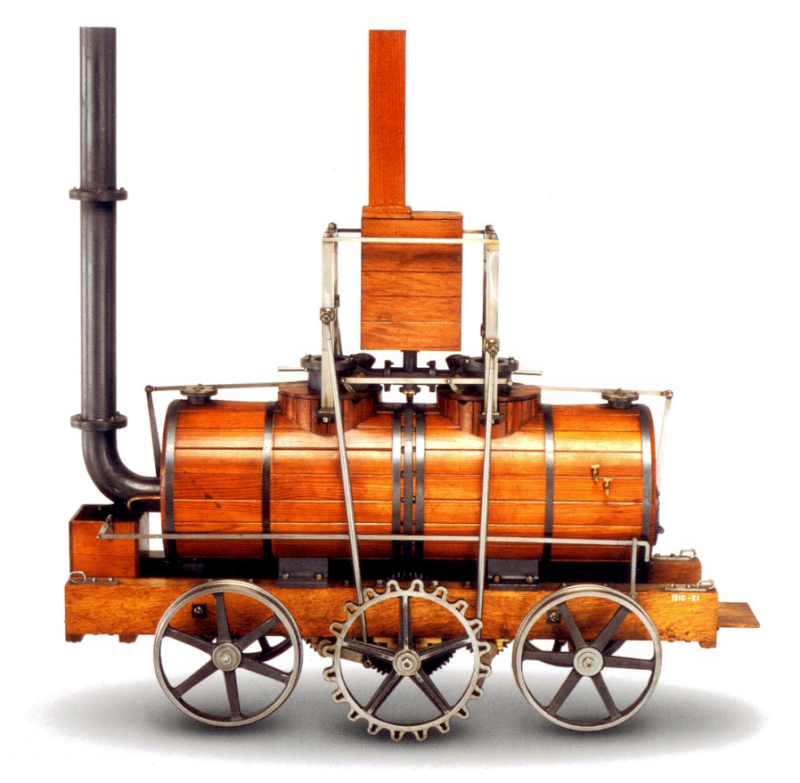

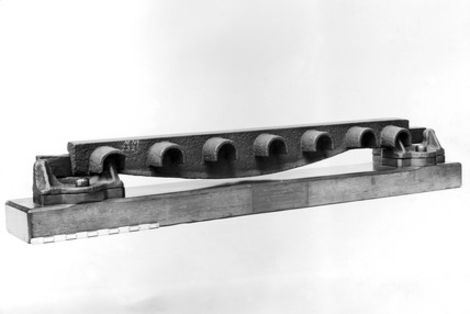

To save construction costs, the rack was cast directly into the side of the rails, and surprisingly enough some rails and a set of wheels from one of these earliest successful locomotives still exist.

There are obvious mechanical issues with this set up, but some of the engines worked for over a decade, and there were even attempts to build systems of this nature outside of England (although I don’t think any of them ran successfully, as building a locomotive in 1812 required machining precision that was difficult if not impossible to obtain outside of England at the time).

It was only a year or too later that another, a more obvious idea was tried: just add more axles to lower the axle loads:

This locomotive, the Puffing Billy was built with eight wheels to spread the weight of the locomotive over more sections of rail. It worked. But as soon as the railway it ran on was relaid with wrought iron rails, it was rebuilt on four wheels. It still exists, and is the oldest complete locomotive preserved today.

So there you have it. The steam locomotive was invented before spring and rail technology was there to (literally) support it. But there were clever workarounds.