Prior to WWII, the Soviet Union and, earlier, the Russian Empire, mostly stayed out of the competition on transatlantic passenger routes. Which is understandable, since the country certainly had other, more pressing priorities. However, the Soviets exited WWII as one of the world’s two preeminent superpowers, and, one of the things they wanted to do as part of signaling to the world their arrival as a leading force on the geopolitical stages was to develop a modern merchant shipping fleet that would carry the Soviet red banner to every major port in the world. In the immediate postwar years, the Soviets concentrated on salvaging sunken German ocean liners from waters they now controlled, rebuilding them at expense of time and effort (but not so much in money, given labor rates), but, eventually, they came to realize that rebuilt 1920s ships were not really the way to demonstrate their technological and economic resurgence to the West, so new builds eventually became the order of the day.

The 1960s saw the largest and most luxurious class of Soviet passenger ships ever built, the famed Five Poets sisters, as they were each named after a famous author. As no Soviet shipyard had ever built a passenger ship as big and complex, construction was outsourced to VEB Matthias-Thesen Werft in Wismar, East Germany. I have heard from more than one maritime historian that the ships’ construction was done as part of East Germany’s war reparations to the Soviet Union, but I have never found any official confirmation of that, so it might just be an urban legend. Certainly, the Soviets did extract considerable reparations from East German industry after the war, and West Germany did build some ocean liners for Israel as reparations, but that was mostly over by the 1960s. I expect if it was true, there would be a written source somewhere, likely the Soviets did pay for these ships.

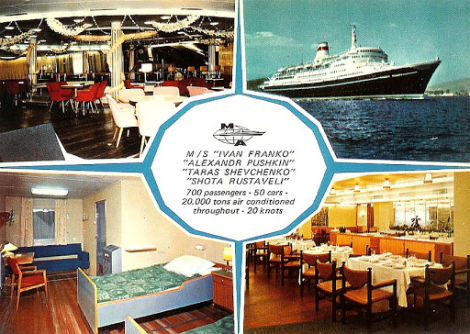

Originally, 4 vessels were ordered, but, late in the process, a 5th was added. They were:

Ivan Franko – delivered 1964 to the Black Sea Shipping Company (BLASCO) of Odessa, Ukrainian SSR, used initially in service on domestic and international routes between ports along the Black Sea and Eastern Mediterranean from Odessa

Aleksandr Pushkin – delivered 1965 to the Baltic Shipping Company of Leningrad, Russian SFSR, for transatlantic service between Leningrad and Montreal.

Taras Shevchenko – delivered 1966 to BLASCO

Shota Rustaveli – delivered 1968 to BLASCO

Mikhail Lermontov – delivered 1972 to Baltic Shipping for Leningrad-New York service. Soviet passenger ships had largely been barred from US ports, but thawing relations under Richard Nixon made New York service a possibility for the first time, and Mikhail Lermontov was added to the class. Incidentally, this was the last new transatlantic ocean liner service ever introduced to New York, since all the major companies were failing in the face of jet airliner competition and cutting their services as quickly as possible, with 1971 being the biggest year for shipping companies ending transatlantic services. But, the Soviets were not concerned with the economics, only showing the flag for PR purposes, and were happy to run Mikhail Lermontov nearly empty if they needed to.

All ships were built to largely identical plans, with modern, streamlined superstructures and funnels and elegantly raked bows. Their hulls were unusually strong, built to cope with Arctic sea ice, and featured a high level of compartmentalization for damage control, allowed ready adaptability to military use. The interiors were described as modern and comfortable, but not exactly luxurious – pleasant enough, but clearly built to a price. They had an unusually high percentage of inside cabins and cabins without private bathrooms for the era, as well as saltwater taps and the availability of 6 berth rooms (both features that disappeared on Western liners after WWII) – but, they were fully air conditioned throughout and featured swimming pools with retractable glass roofs for all weather comfort, things that would become common on cruise ships a decade later.

The ships featured a cruising range of 10,000 nm without refueling or re-provisioning, which aided in use as military sea lift vessels if required, and were fitted with fuel efficient twin Polish-built Sulzer-Cegielski diesel engines, delivering 20,700hp and a top speed of 20.5 knots.

As built, the ships measured about 19,900 gross tons and 578 ft. long, carrying 650 passengers in 2 classes. BLASCO’s vessels could carry another 500 “deck” passengers without cabins for port-to-port service in the Black Sea.

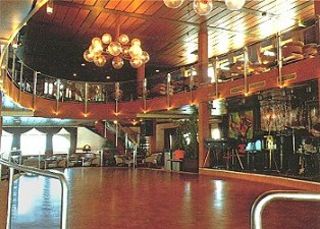

Between 1972-1977, all five ships returned to their builder’s yard for considerable rebuilding, with the forward superstructure enlarged and the bridge moved forward, pushing their size to just over 20,000 tons, and adding the first discotheques on Soviet-registerd vessels. By the 1970s, the ships spent most of their time on cruise service – principally for the Charter Travel Club – also known as CTC Cruises or CTC Lines. CTC was a British-based company, headquartered in London, but entirely owned by the Soviet state and managed through their embassy, but operated as a for-profit corporation. CTC marketed cruise packages on Soviet registered ships to British, Australian, and New Zealand customers as a means of earning foreign hard currency.

As best as can be figured, Mikhail Lermontov ended service to New York in 1979, when US-Soviet relations became strained over the Afghan invasion, and switched to full-time cruise use at that point. By the end, Mikhail Lermontov was the only other liner besides Cunard Line’s Queen Elizabeth 2 still offering scheduled service to the United States. Aleksandr Pushkin ended service to Montreal in 1980, leaving Polish Ocean Lines’ Stefan Batory as the only remaining vessel on that route, for a few more years. BLASCO’s intercity coastal and ferry-like services were more insulated from airline competition, and their ships continued to alternate liner voyages with cruises through the 1980s.

Aleksandr Pushkin was transferred from Baltic Shipping to the Far East Shipping Company (FESCO) of Vladivostok, Russian SFSR in 1985 and began focusing more heavily on charter cruises for Australian and New Zealand travel agencies.

All 5 ships underwent additional refurbishment work between 1980-1982, adding private bathroom facilities to all cabins, extending the aft superstructure for more open deck terrace space, and modernizing the interiors, all to improve their appeal to Western cruise passengers.

Disaster struck on February 16, 1986, when Mikhail Lermontov hit rocks in shallow waters off Cape Jackson, outside Picton, New Zealand, while under the control of the harbor master. There were allegations that the pilot was overworked and not properly rested, and he apparently believed the channel to be twice as wide as it actually was. The ship was operating a 14-night cruise of the South Pacific for CTC, loaded with 372 passengers (mostly Australian, but also 36 Britons, 6 Americans, 2 West Germans, and 1 from New Zealand). The harbor pilot, Captain Jamison, believed the channel was much wider than it was, and also decided to sail in closer to the shore to give the passengers a better view of the cape. The Soviet captain immediately took command and ordered the ship beached , but the water rushing through the 40-foot gash caused an almost immediate failure of all electrical and mechanical systems, leaving the ship completely powerless. Within a little less than 5 hours, Mikhail Lermontov slipped beneath the waves. A civilian ferry and several fishing boats, along with the Royal New Zealand Navy, responded rapidly, resulting in the rescue of 742 out of the 743 passengers and crew on board. A Russian crew member trapped below decks in the flooding was the only fatality. Responsibility for the loss became the subject of a lengthy diplomatic dispute between the Soviet, and later Russian, governments and New Zealand that wasn’t resolved until some 20 years later.

As far as the other vessels, BLASCO wound up under the control of the now independent Ukrainian government in 1991, was partially privatized, but collapsed in bankruptcy in 1996. Taras Shevchenko was sold to Odessa-based Ocean Agencies Ltd. in 1997 and resumed operations in 1998, but was quickly laid up due to financial difficulties. She underwent a through refurbishment and refitting in 2003 for expedition cruises to Antarctica for Russian-based Antarktika JSC, but the venture was not successful and she was laid up again in 2004, and finally scrapped in Alang, India in 2005 under the name Tara.

Shota Rustaveli was also acquired by Ocean Agencies in 1997, but laid up again in 1998. In 2000, she was sold to St. Vincent and the Grenadines-based Kaalby Shipping and resumed service as the charter cruise ship Assedo (Odessa backwards). Although well maintained and reasonably successful in charter work, high scrap metal prices and stiff competition sent Assedo to the breakers yard in Alang in 2003.

Ivan Franko was laid up in 1997, sold to a metals trading company who renamed her Frank, then quickly resold her to Indian ship breakers in Alang for demolition.

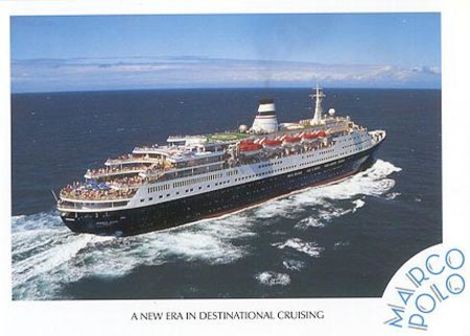

The lone survivor (till now, anyway) is the second ship of the class. Aleksandr Pushkin was laid up in 1990 and offered for sale. British businessman Gerry Herrod bought her from the Soviets in February 1991 and sent her to a shipyard in Greece for an extensive rebuilding. The ship emerged in 1993 as the fashionable Marco Polo for Herrod’s new UK-based Orient Lines venture. Now measuring over 22,000 tons and carrying 848 passengers in fully modernized interiors, Orient took advantage of the rugged, ice-strengthened hull and long cruising range, utilizing Marco Polo on lengthy expedition-style cruises to remote ports around the world, with a heavy educational and cultural enrichment component.

Orient Lines was acquired by Norwegian Cruise Line in 1998, and, after initially proposing a fleet expansion and investment program, the plug was pulled in 2006 with the total wind-down of the Orient Lines brand. Marco Polo went to a Greek investment company who chartered her to Transocean Tours of Germany through 2010, when she went to UK-based Cruise & Maritime Voyages. CMV shut down operations in early 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and collapsed in bankruptcy in June. Marco Polo, the last ocean-going Soviet passenger ship afloat, currently remains laid up in a limbo state with an uncertain future.