Welcome to This Date in Aviation History, getting of you caught up on milestones, important historical events and people in aviation from August 4 through August 7.

August 4, 1954 – The first flight of the English Electric Lightning P.1A. The world entered the nuclear age on August 6, 1945 when the US dropped the first of two atomic bombs on Japan in the hopes of ending the war and avoiding a bloody invasion. Though we live today with the Damoclean sword of intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBM), it was 14 years until the Soviets fielded the world’s first operational ICBM in 1959. During those intervening years, the only method of delivering a nuclear weapon to a target was with high-flying bombers of ever-increasing speed in the hopes of outrunning defensive fighters. Therefore, it was vital to intercept the nuclear-armed bombers as early as possible, and this called for a special breed of fighter aircraft, one that could take off at a moment’s notice and fly as fast as possible to get to the bombers before the bombers could reach their target.

The idea of an interceptor was not new, and their use dates all the way back to WWI. But in the jet age, supersonic speed became the all important factor in their development. When the British Aircraft Corporation Lightning (following BAC’s merger with English Electric in 1960) entered service in 1960, it was the Royal Air Force’s only interceptor capable of Mach 2 speed. But this modern bomber hunter traces its roots all the way back to 1947, when English Electric, the maker of the Canberra bomber, was awarded a contract to develop a supersonic research aircraft. To achieve supersonic speeds, English Electric designers knew they would have to employ a swept wing, but they first had to determine the optimal amount of sweep. To do this, English Electric contracted with the Irish firm Short Brothers to create the Short SB.5, a scaled down research aircraft whose wing and tailplane could be adjusted to different angles for testing. Based on data gathered from the SB.5, English Electric chose an untapped wing with a severe 60-degrees of sweep, and the Lightning received its unique shape.

Another feature unique to the Lightning was its engine layout. Rather than place the two turbojet engines side-by-side, English Electric stacked the engines one on top of the other. This arrangement gave the Lightning the power to reach Mach 2 while also reducing drag and minimizing the frontal area of the fighter. The prototype Lightnings were powered by a pair of Armstrong Siddeley Sapphire non-afterburning (or non-reheating to the British) axial flow turbojets. While the Sapphire was not as powerful as the Rolls-Royce Avon turbojets which would be fitted on production aircraft, the Lightning still passed the sound barrier on its maiden flight. Following the successful testing of the prototypes, the P.1B, which featured the new Avon turbojet engines, took its first flight 1957 and, with the addition of a crude afterburner, allowed the Lightning to reach Mach 2.

The new interceptor entered service with the RAF in 1960 as the Lightning F1, and its primary mission was to intercept Soviet bombers and provide protection to airfields so British nuclear bombers, known as the V Force, could take off. Subsequent variants added to the Lightning’s capability with more weapons and improved radar. With so much power available to Lightning pilots, the interceptor could achieve an altitude of 36,000 feet in less than three minutes, and tests showed that the Lightning was capable of intercepting a high-flying Lockheed U-2 spyplane. But all that speed came at a cost. The Lightning burned fuel voraciously, and many of its missions were determined simply by the amount of fuel it could carry. While the RAF was the primary operator of the Lightning, it was also exported to Kuwait and Saudi Arabia. A total of 337 aircraft were produced, but in its nearly 30 years of service, the Lightning was never used in combat, and only claimed one aircraft shot down: an unmanned RAF Hawker Siddeley Harrier that was flying towards East Germany after its pilot ejected. The RAF retired their Lightnings in 1988, but a small number of aircraft still flying in the hands of private pilots.

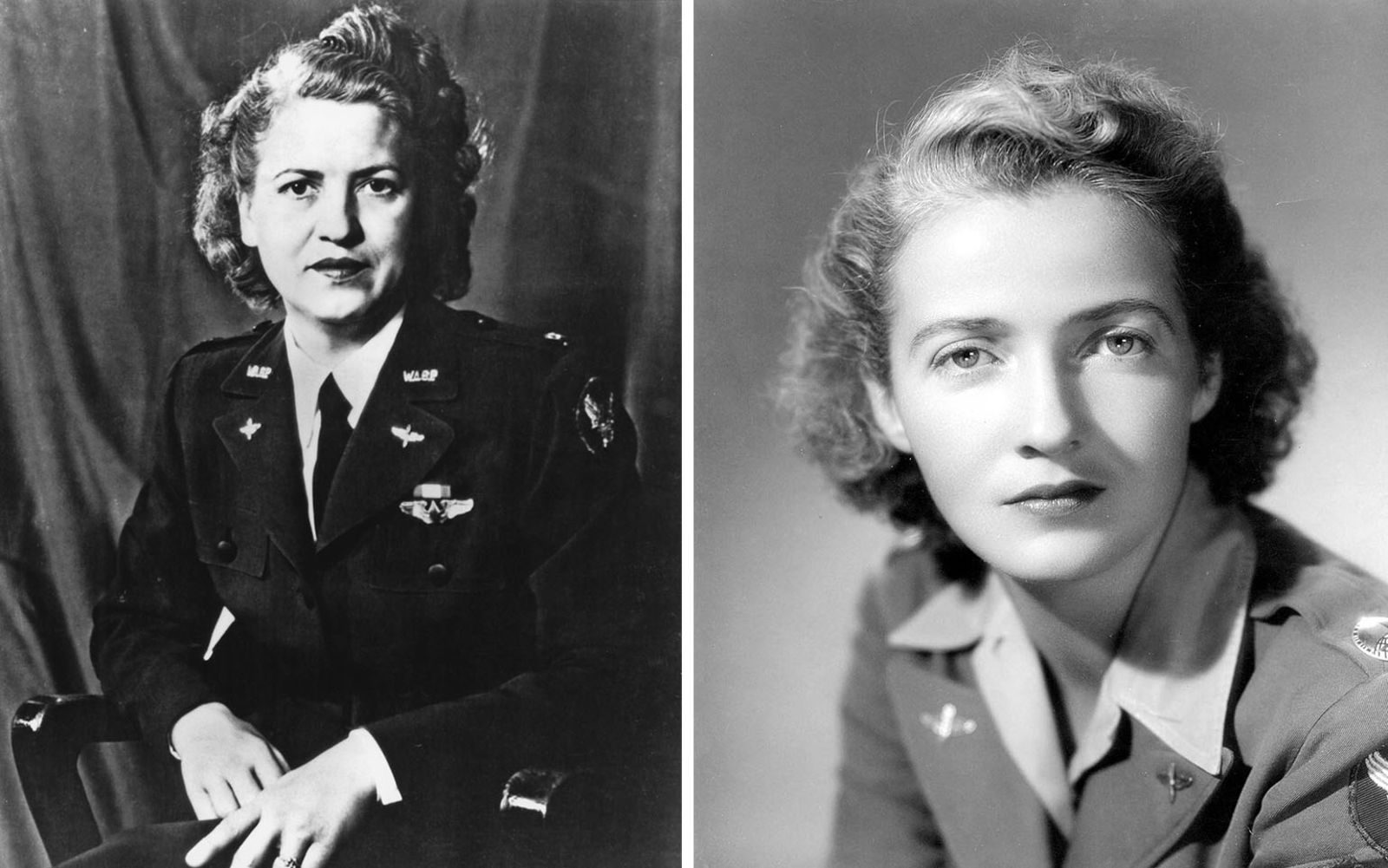

August 5, 1943 – The Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP) is formed. Prior to the enactment of the Women’s Armed Services Integration Act in 1948, which enabled women to serve as permanent, regular members of the US armed forces, most American women served in non-military support organizations such as the US Navy’s Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service (WAVES) and the US Army’s Women’s Army Corps (WAC). Before that time, the only way for a woman to serve officially in the active duty military was as an Army nurse or in other support roles. During WWII, about 400,000 American women answered their country’s call, and more than 500 died, 16 from enemy fire. But with so many American men fighting overseas or serving in the military stateside, jobs that were traditionally filled only by men were being very capably filled by women for the first time. Rosie the Riveter became a symbol of the new American workforce helping to supply Arsenal of Democracy with planes, tanks and ammunition, but for the first time, women began serving as pilots.

Before the war, pioneering aviators Jacqueline “Jackie” Cochran and Nancy Harkness Love each submitted a proposal to the Army to train women pilots to ferry aircraft from the factories where they were produced to their assigned bases or to points of embarkation overseas. They argued that every woman who flew an airplane stateside would free up one man for combat flying in Europe or the Pacific. Despite the lobbying efforts of First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, their requests were denied, so Cochran traveled to England where she joined the British Air Transport Auxiliary, becoming one of the first American women to fly a military aircraft. In 1942, Love oversaw the creation of the Women’s Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron (WAFS), which began by ferrying US Army Air Forces trainers and light aircraft, but eventually transitioned to fighters, bombers and large transports. Cochran returned to the US as the WAFS started flying and, with approval from General Henry “Hap” Arnold, she oversaw the formation of the Women’s Flying Training Detachment (WFTD) in the summer of 1942. The two groups worked independently and well, and they were merged into the Women Airforce Service Pilots in 1943 under the direction of Cochran to codify training and operational standards. Though more than 25,000 women applied for the program, only 1,074 earned their wings. Primary training took place at Avenger Field in Sweetwater, Texas, and their duties included not only ferrying aircraft but also carrying out test flights and towing targets for gunnery practice.

However, while women were doing the same work as their male military counterparts, the Army still resisted allowing them to become pilot officers. Cochran continued to put pressure on the Army Air Forces to grant the WASPs a commission into the USAAF, but Arnold resisted. Finally, Cochran issued an ultimatum: give the WASPs a commission or disband the group. The Army, faced with a glut of pilots and trainees, chose to disband the unit in December 1944 rather than create women officers. At the time the WASPs were disbanded, they had delivered 12,650 aircraft around the country and suffered 38 fatalities due to accidents. Despite giving their lives in service to their country, the Army did not afford any military honors at the funeral of a fallen WASP pilot. The pilot’s body was shipped home at family expense, and the family was not allowed to drape the American flag on the coffin. After the war, WASP veterans were barred from the honor of burial at Arlington National Cemetery until legislation was signed by President Barack Obama in 2016 allowing their interment. Though the WASPs opened the door for women military pilots, 30 more years would pass before Barbara Allen Rainey earned her wings in 1974 to become the first woman commissioned as a pilot in the US armed forces. She served in the US Navy until she lost her life in a training accident in 1982. The US Air Force followed suit in 1978 when it accepted its first female pilot, but women were still barred from official combat roles until 1993.

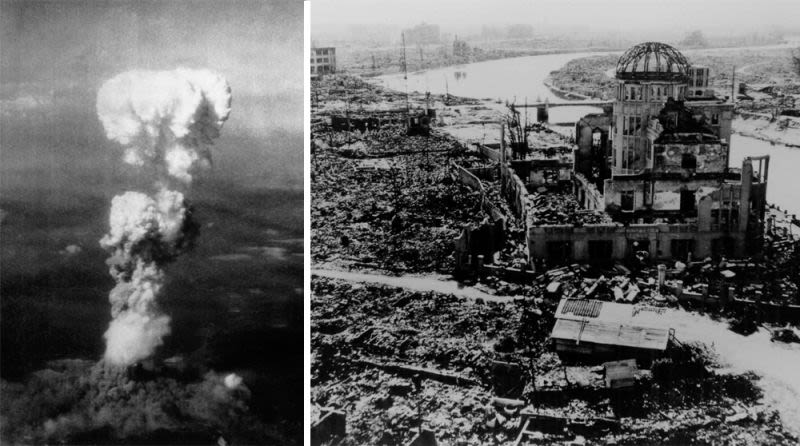

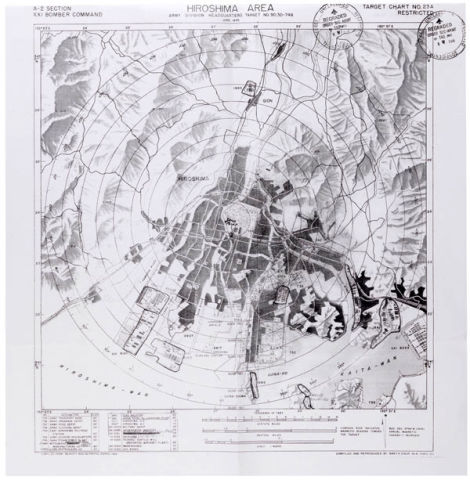

August 6, 1945 – The United States drops the Little Boy atomic bomb on the Japanese city of Hiroshima. Following the American victory in the Battle of Midway in June 1942, the tide of battle in the Pacific turned decisively to America and her allies. The methodical island hopping campaign began, as America captured strategic islands for the construction of air bases while bypassing large groups of entrenched Japanese soldiers on other islands and cutting off their flow of supplies. With the capture of Guam, Saipan and Tinian in June and August 1944, the US now had bases close enough to begin flying Boeing B-29 Superfortresses on strategic bombing missions against Japan. But even the most modern bomber in the world could only be so accurate from high altitude, and with so much of the Japanese war production spread throughout the cities and into people’s homes, the bombing wasn’t terribly effective. Even after General Curtis LeMay changed tactics in 1943 to the firebombing of Japanese cities, resulting in huge loss of life, Japan fought on. It appeared that an invasion of the island would be the only way to end the war.

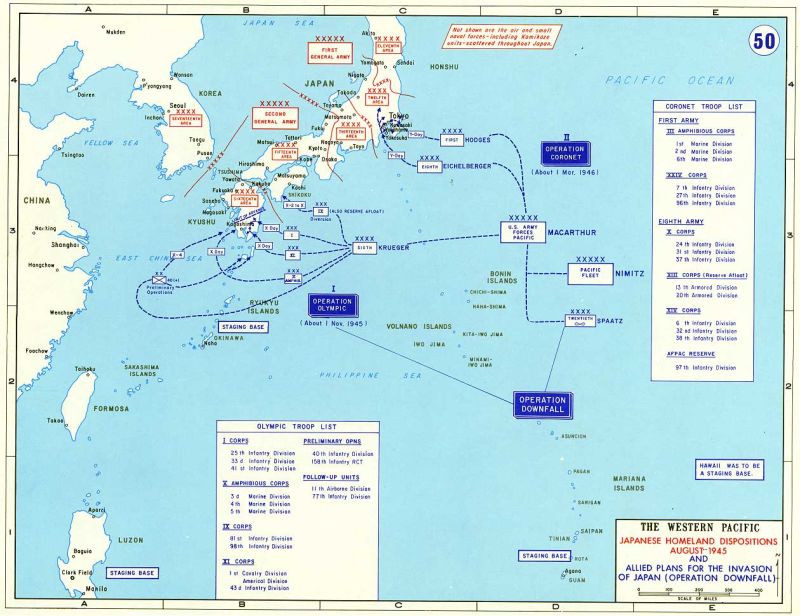

In the largest amphibious assault of WWII, the US secured the island of Okinawa on June 22, 1945 to serve as a launching point for the planned Operation Downfall, a two-part invasion of Japan that was slated to begin on November 1, 1945. American war planners knew that an invasion would be costly, with initial estimates expecting 130,000-220,000 Allied casualties. Once it became clear that the Japanese were preparing defenses at the intended landing sites, casualty estimates leapt to 1.7-4 million, with 400,000-800,000 dead. The US went so far as to produce a half million Purple Heart medals in preparation for the invasion. But could the war be ended without an invasion? Could the Americans strike such a devastating blow that the Japanese would finally capitulate?

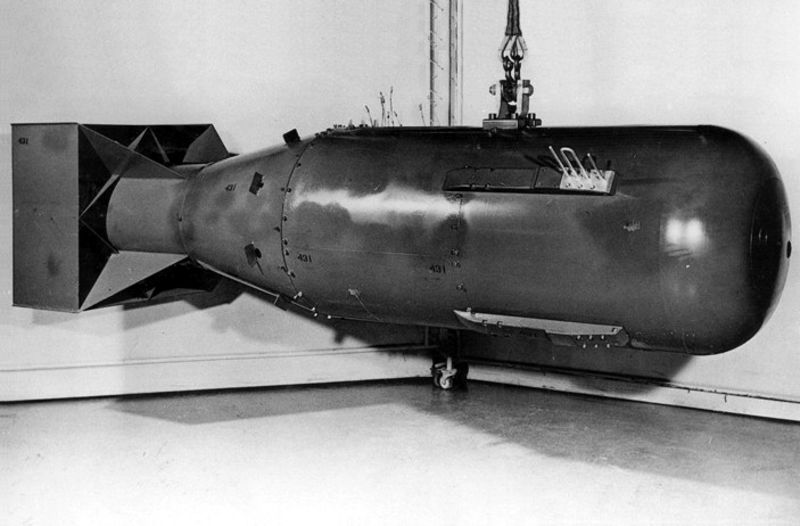

Development of a nuclear bomb in the US dates back to before the war, when scientists who had fled Nazi Germany came to America with dire warnings of German advances in atomic science. In 1939, the Americans began working on their own bomb to counter the perceived German threat, with Berlin as a potential target. But work on the bomb progressed slowly, and the first successful test was not carried out until July 1945, after the war in Europe had ended. The organizational effort to create the group of pilots and planes that would drop the new weapon had begun in 1944 with the creation of the 509th Composite Group under the command of Colonel Paul Tibbets at Wendover Army Air Field in Utah. The 509th would be flying the Silverplate B-29 Superfortress, which was specially modified to carry the new bombs and fitted with fuel injection, reversible pitch propellers, and special bomb bay doors that opened and closed quickly. To save weight and carry more fuel, all defensive armament was removed along with all armor plating.

On July 26, 1945, the Allies issued the Potsdam Declaration which called for the unconditional surrender of Japan and threatened “prompt and utter destruction” if they did not comply. The Japanese, who had already shown their fanatical desire to fight to the death time and time again throughout the Pacific campaign, rejected the Allies’ call for surrender. Faced with the specter of a costly invasion, the US decided to drop the first atomic bomb on Japan. After consideration of numerous cities, Hiroshima was chosen as the first target because of its large military base, but also chosen the Americans wanted a target that was visible enough to have a psychological impact on the Japanese.

Tibbets and his crew departed Tinian in their B-29, named Enola Gay after Tibbets’ mother, for the six-hour flight to Hiroshima. Over Iwo Jima, Enola Gay was joined by two other B-29s. The first was named Great Artiste and was loaded with instruments to measure the explosion. The second, an unnamed B-29, served as a photo ship. Thirty minutes from the target, mission commander Captain William Parsons armed the Little Boy atomic bomb. Tibbets started the bombing run completely unopposed over the unsuspecting city, and released the bomb at 8:15 am (Hiroshima time). The massive explosion killed 70,000-80,000 people in the city, both soldiers and civilians, roughly 30% of the population. More than 70,000 were injured, and 4.7 square miles of the city were destroyed as massive fires engulfed the wooden buildings in the city. Those residents who survived the blast suffered horrifying burns, radiation sickness, and a host of other maladies. The next day, President Harry S. Truman gave an address to the nation, and offered Japan a grave warning:

We are now prepared to obliterate more rapidly and completely every productive enterprise the Japanese have above ground in any city. We shall destroy their docks, their factories, and their communications. Let there be no mistake; we shall completely destroy Japan’s power to make war. . . . If they do not now accept our terms they may expect a rain of ruin from the air, the like of which has never been seen on this earth. Behind this air attack will follow sea and land forces in such numbers and power as they have not yet seen and with the fighting skill of which they are already well aware.

Despite Truman’s promise of more nuclear attacks, the Japanese government remained silent, and did not surrender. So Truman made good on his word. The bombing of Hiroshima was followed three days later by a second atomic attack, this time on the city of Nagasaki carried out by a Silverplate B-29 nicknamed Bockscar. It was only after this second attack that the Japanese government finally agreed to an unconditional surrender on August 15, 1945, bringing an end to the Second World War.

Short Takeoff

August 4, 1971 – The first flight of the AgustaWestland AW109, a twin-engine lightweight helicopter and the first all-Italian helicopter to enter mass production. Agusta (now AgustaWestland, a subsidiary of Leonardo-Finmeccanica) originally designed the A109 in the late 1960s with a single engine, but it was soon evident that a second engine was necessary to provide the necessary lifting power. Today, the AW109 is powered by a pair of Pratt & Whitney Canada PW200 turbine engines and can accommodate up to seven passengers at a top speed of just under 200 mph. The AW109 entered service in 1976 and is flown by military and government agencies all over the world, and commonly serves as an air ambulance or for corporate transportation.

August 6, 1996 – The first flight of the Kawasaki OH-1, a military scout and observation helicopter developed for the Japan Ground Self-Defense Force and the first helicopter entirely produced in Japan. Nicknamed Ninja, the OH-1 was created as a replacement for the Hughes OH-6 Cayuse light observation helicopter (LOH or “Loach”) and entered service in 2000. The OH-1 is powered by two Mitsubishi TS1 turboshaft engines which provide a maximum speed of 173 mph, and is fitted with an asymmetric Fenestron tail rotor that reduces noise and vibration. Development included an attack variant that was rejected in favor of the Boeing AH-64 Apache. A total of 38 helicopters have been produced and the Ninja remains in production.

August 6, 1945 – The death of Richard Bong, one of the United States’ most decorated fighter pilots and the highest-scoring American ace of WWII. Bong was born in Superior, Wisconsin on September 24, 1920, and received his wings in January 1942. During the war, Bong flew the Lockheed P-38 Lightning exclusively, and made the first of his 40 total victories on December 27, 1942. For his service, Bong was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor in 1944 and was sent home to help sell war bonds. Following the war, Bong became a test pilot for Lockheed, but was killed when the fuel pump of his Lockheed P-80 Shooting Star malfunctioned during takeoff. Bong ejected, but was too close to the ground for his parachute to open fully.

August 7, 1990 – Operation Desert Shield begins. Following the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait on August 2, 1990, US President George HW Bush deployed US forces to Saudi Arabia to protect America’s strategic ally from further aggression by Iraqi President Saddam Hussein. Air assets of the US Air Force and US Navy teamed with aircraft from Saudi Arabia, Great Britain and France, eventually forming a coalition of 48 nations resolved to oust Saddam from Kuwait. Five months of air operations to protect the buildup of 120,000 soldiers saw Operation Desert Shield become Operation Desert Storm, with the Coalition invasion to liberate Kuwait beginning on January 17, 1991 in what would come to be known as the First Gulf War.

August 7, 1963 – The first flight of the Lockheed YF-12, a two-seat interceptor variant of the Lockheed A-12 reconnaissance aircraft. The YF-12 was developed in response to an Air Force requirement for an interceptor to replace the Convair F-106 Delta Dart that would be capable of speeds up to Mach 3. Following the cancelation of the North American XF-108 Rapier, Lockheed’s Kelly Johnson proposed version of the A-12 that would be fitted with the Hughes AN/ASG-18 fire control system and armed with Hughes AIM-47 Falcon missiles, specially modified to be fired by the YF-12 from internal missile bays. The Air Force ordered three prototypes and, during flight testing, the YF-12 set speed and altitude records for an interceptor of 2,070 mph and 80,257 feet. The YF-12 program was canceled in 1968, though the prototypes served as NASA test aircraft until 1979.

August 7, 1951 – The first flight of the McDonnell F3H (F-3) Demon, a single-seat fighter and interceptor developed for the US Navy as the successor to the McDonnell F2H Banshee. Unlike other fighters that were swept-wing variants of earlier sraight-winged aircraft, the Banshee was designed from the start with swept wings in an effort to counter Soviet fighter aircraft, though it was not capable of supersonic flight. Problems with engines plagued the Demon throughout its service life, and it was retired before it could serve in the Vietnam War. Despite difficulties with the Demon’s development, it ultimately served as the basis for the design of the McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom II, which replaced the Demon in Navy service.

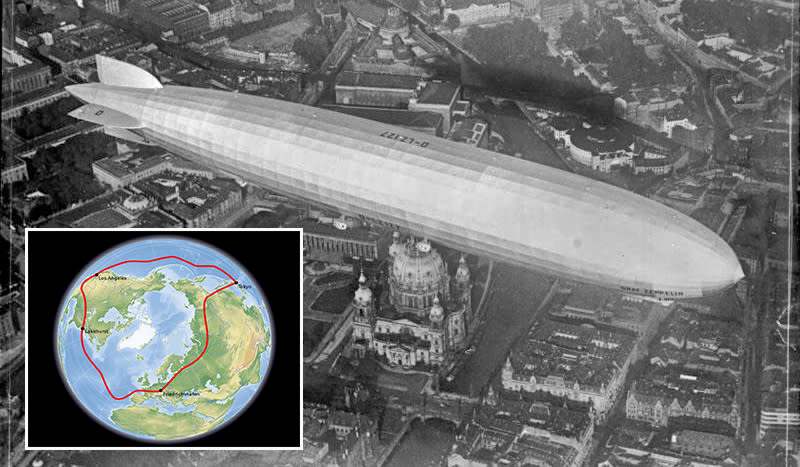

August 7, 1929 – The Graf Zeppelin (LZ-127) begins the first circumnavigation of the world by air. Before the great ocean-spanning airliners, Zeppelins were the primary means of intercontinental travel. The Graf Zeppelin took its maiden flight on September 18, 1928, and completed its first flight to the United States the following month. At the urging of US newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst, the Graf Zeppelin began its eastward flight around the world by leaving Lakehurst, New Jersey and flying for Friedrichshafen in Germany before heading across the Soviet Union, Siberia, Japan, and then across the Pacific Ocean and back to New Jersey. The circumnavigation took 12 days to complete and covered 21,000 miles. On board was Hearst reporter Lady Grace Drummond-Hay who became the first woman to travel around the world.

Connecting Flights

If you enjoy these Aviation History posts, please let me know in the comments. And if you missed any of the past articles, you can find them all at Planelopnik History. You can also find more stories about aviation, aviators and airplane oddities at Wingspan.