Welcome to This Date in Aviation History, getting of you caught up on milestones, important historical events and people in aviation from March 6 through March 8.

March 8, 2014 – The disappearance of Malaysian Airlines Flight 370. With the arrival of the airplane, and later the commercial airliner, passengers were able to travel to far flung corners of the globe, and geographical barriers such as mountain ranges and oceans no longer barred passage for travelers. But flying over some of the more remote parts of the world is not without risk. In the earliest days of flight, it was not uncommon for an intrepid pilot trying to find the shortest route over a mountain or trying to cross open water never arrived at his destination and was never heard from again. Hundreds of aircraft remain missing to this day, with no trace of either bodies or wreckage. Back in the days before satellites and cell phones, disappearances such as these were easily understood. But in our modern world of hyper-connectivity, it seems almost unfathomable that a huge airliner full of passengers could go missing without a trace or without explanation. But that is exactly what happened to Malaysian Airlines Flight 370.

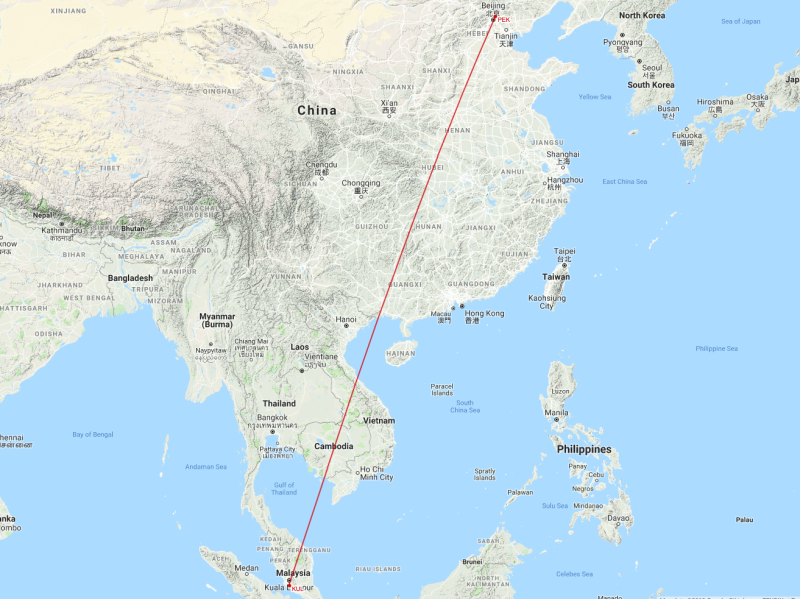

MH370 was regularly scheduled Boeing 777 (9M-MRO) service from Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia to Beijing China. On board the flight were 12 Malaysian crew members and 277 passengers hailing from 14 different nations. Captain Zaharie Ahmad Shah, an experienced pilot with over 18,000 hours of flying time, was in command, with First Officer Fariq Abdul Hamid at his side. The scheduled flight time to Beijing was 5.5 hours, and the 777 carried enough fuel for 7.5 hours of flight, enough to safely divert should any troubles arise. MH370 took off on schedule at 00:42 local time and reached its planned cruising altitude of 35,000 feet. Thirty-eight minutes after takeoff, Captain Shah acknowledged instructions from the ground to contact Vietnamese air traffic controllers. It was the last time anybody was heard from onboard MH370.

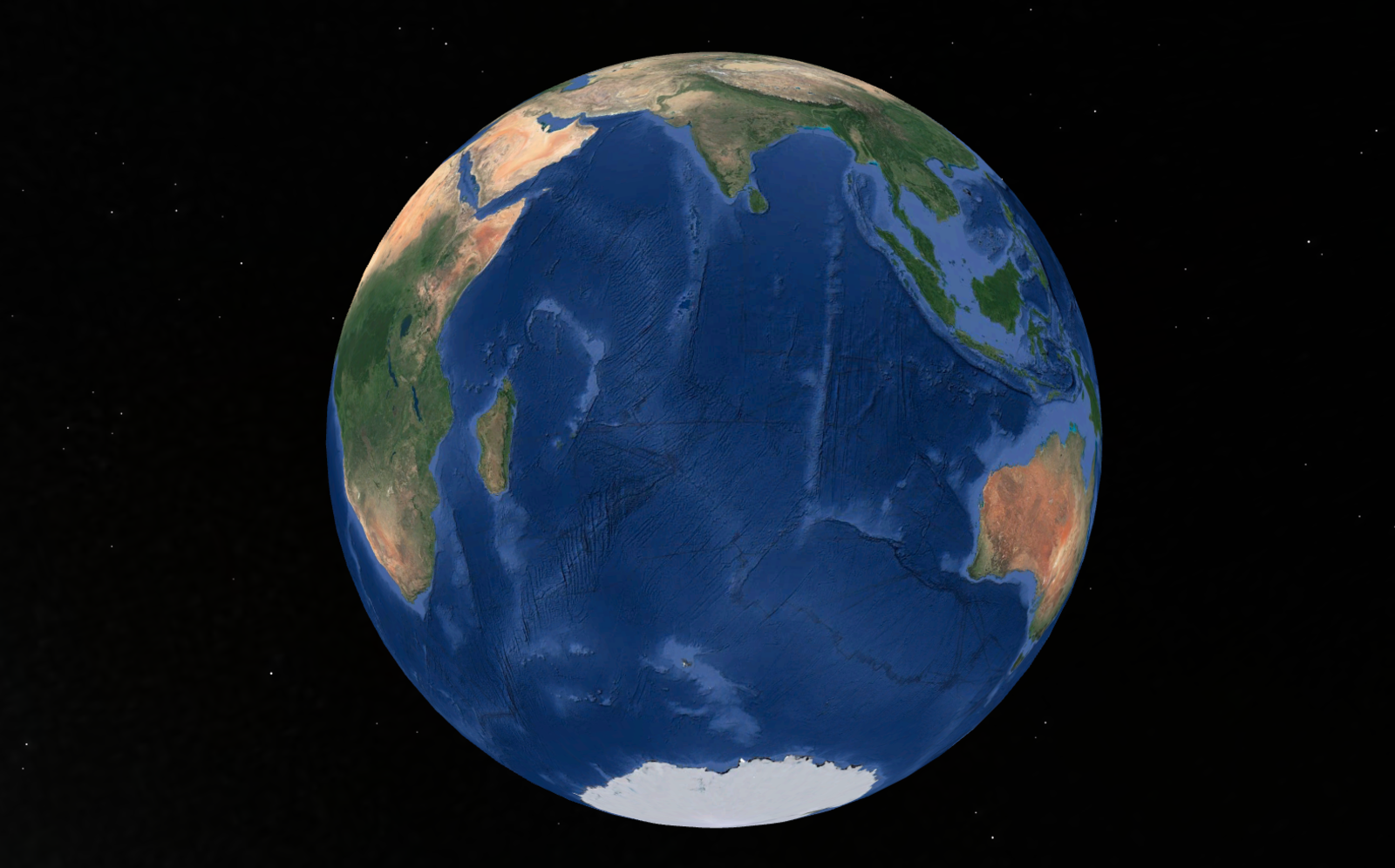

Two minutes later the Shah’s final transmission, the transponder stopped sending signals to the ground, and the aircraft, tracked by ground radar, changed course and headed westward, back across Malaysia, and then out over the Adaman Sea. Military radar tracked the airliner as it headed toward the Nicobar Islands before all primary radar contact was lost. Though MH370 no longer showed up on radar scopes, that didn’t necessarily mean that the airliner was completely undetectable. Though the transponder, which identifies an aircraft and its altitude, had been turned off, the aircraft communications addressing and reporting system, or ACARS, continued making attempts to contact the ground. This system automatically sends various types of messages, such as when an aircraft takes off or lands, when the doors are opened, or when events happen with the engines. Though the ACARS had been turned off, the satellite data unit, or SDU, continued to make attempts to contact the ground. While these attempts at contact didn’t provide specific positional information, they did allow searchers to determine the distance from the satellite, and thus calculate a likely path for the aircraft. One path was over land, while the other traced a course out over the southern Indian Ocean. These signals finally stopped 7.5 hours after takeoff, presumably when MH370 ran out of fuel and crashed into the ocean.

The search for the airliner initially focused on its last known location, but soon shifted to the waters west of Australia. In the most expensive search and rescue operation in history, 1.8 million square miles of the Indian Ocean were searched along the suspected flight path of MH370, yet not a single piece of debris was found, let alone any sizable wreckage. The flight data recorders had long since stopped sending locator signals, and any wreckage that sank could be as much as 15,000 feet under water. More than two years later, some pieces of wreckage, including a wing flap that was positively identified as belonging to MH370, washed up on beaches in the western Indian Ocean. But the bulk of the aircraft has yet to be found, despite another search mission that was started in January 2018.

With no wreckage to scrutinize and no flight data to analyze, investigators are left with only assumptions as to what happened to the flight. Two Iranian passengers, who were flying on one-way tickets using stolen passports, were later deemed to be refugees and not considered as possible terrorists. MH370 was also carrying a load of potentially dangerous lithium-ion batteries, but those were shown to have been packaged and loaded according to strict safety guidelines. Scrutiny then turned to Captain Shah. Though he did not show any motive for purposefully flying the plane into the ocean, American investigators did discover simulated flight paths that matched those of MH370's doomed flight on Shah’s home computer.

Even if the wreckage is eventually found, it still may not provide the final answers to what caused the airliner to fly so far off course and continue until its fuel was exhausted. Did the pilot purposefully reprogram the autopilot? Did a catastrophic event cause all on board to lose consciousness while the aircraft continued on its own? We may never know. New systems, such as the Global Aeronautical Distress and Safety System (GADSS) developed by the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), along with emerging data gathering technology called GlobalBeacon which uses data provided by existing ADS-B equipment, will soon be able to update an aircraft’s position anywhere on the globe every minute. But until those new systems become operational, Malaysian Flight 370 will serve as a reminder that, no matter how small the world has become, it remains a vast place, and that no matter how connected we are, it is still possible to become utterly lost.

Short Takeoff

March 6, 2003 – The first flight of the AgustaWestland AW609, a twin-engine tiltrotor VTOL aircraft being developed for the civilian market. Similar to the Boeing V-22 Osprey, the AW609 is capable of vertical takeoff and landing, with transition to forward flight provided by turboprop engines mounted in swiveling nacelles on the end of the wings. AgustaWestland plans to market the AW609 to VIP customers and the offshore oil and gas industry. Development was slowed after the crash of the second prototype in October 2015 which killed two test pilots. For still unknown reasons, the aircraft broke up in midair during high speed testing. Certification of the AW609 is currently scheduled for the end of 2019, and AgustaWestland is considering a site in the US for production.

March 6, 2003 – The launch of Hooters Air. Hooters Air was founded by Robert Brooks, the owner of Hooters of America, a restaurant perhaps better known for the revealing attire worn by its waitresses than for its food. Brooks acquired Pace Airlines in 2002, and rebranded the jets in Hooters Air livery. The airline focused on the golfing set, hoping to drum up business with passengers, particularly men, who wanted to take flyaway golf trips. Each flight was staffed by two Hooters waitresses in standard Hooters attire in addition to a required complement of flight attendants who wore traditional uniforms. Faced with increased fuel costs following Hurricanes Rita and Katrina, Hooters Air ceased operations on April 17, 2006 after an estimated cost of $40 million was spent on the venture.

March 7, 1975 – The first flight of the Yakovlev Yak-42, a medium-range trijet airliner and the first Soviet airliner to be powered by high-bypass turbofan engines. Developed from the Yakovlov Yak-40, the world’s first commuter trijet, the Yak-42 was primarily intended as a replacement for the Tupolev Tu-134, as well as other older turboprop-powered airliners. The airliner is powered by three Lotarev D-36 high bypass turbofans, has a cursing speed of 460 mph with a maximum range of 2,458 miles, and can accommodate up to 120 passengers. The Yak-24 entered service with Aeroflot in December 1980 and remains in service, flying primarily on routes out of Moscow, with international service to Helsinki and Prague. The Yak-42 was produced from 1979-2003, and a total of 140 were built.

March 7, 1964 – The first flight of the Hawker Siddeley Kestrel. The Kestrel was the second experimental aircraft, following the Hawker P.1127, that explored vertical/short take-off and landing (V/STOL) and ultimately led to the development of the Hawker Siddeley Harrier. Development of both the P.1227 and Kestrel began in 1957 following the introduction of the Rolls-Royce Pegasus vectored-thrust engine. The Kestrel (FGA.1) was an improved version of the P.1227, with fully swept wings, larger tail, and enlarged fuselage to accommodate the larger Pegasus 5 engine. Nine Kestrels were built and flown by the Tripartite Evaluation Squadron comprised of pilots from England, Germany and the United States (where it was known as the XV-6A), and it served as the prototype for pre-production Harriers.

March 7, 1945 – The first flight of the Piasecki HRP Rescuer, a tandem rotor helicopter designed by Frank Piasecki, who was a pioneer in the development of tandem rotor helicopters. To keep the two rotors from colliding, the rear of the fuselage curved upward, giving the Rescuer the nickname “Flying Banana.” It featured a tricycle landing gear, and the fuselage was built of steel tubing covered with doped fabric. The Rescuer was the first US military helicopter with the capacity for a significant number of passengers, and it served the US Navy, US Marine Corps, and US Coast Guard as a transport and cargo helicopter and for air-sea rescue. Piasecki built 28 Rescuers, and it was later developed into the H-21 Shawnee which served extensively in Korea and Vietnam.

March 8, 1954 – The first flight of the Sikorsky H-34. A development of the H-19 Chickasaw, the H-34 was originally designed by Sikorsky as an anti-submarine (ASW) platform for the US Navy. The H-34 was powered by a Wright R-1820 radial engine in the nose that drove the main rotor by a drive shaft that passed up through the cockpit which gave it a maximum speed of 173 mph and capability to carry up to 18 troops or 8 stretchers. The Army chose not to fly the H-34 in Vietnam, but the Marine Corps converted theirs into the first helicopter gunships by adding machine guns and rocket pods. The H-34 served the US until the mid-1960s, but also flew for numerous export countries around the world, as well as in a civilian version called the S-58. A total of 2,108 H-34/S-58s were built.

March 8, 1917 – The death of Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin. Count Zeppelin was born on July 8, 1838 in modern-day Baden Würtemberg and served as a general in the army of Würtemberg before turning his interest to aviation. During the American Civil War, Zeppelin traveled to the United States and observed the use of observation balloons in battle, then returned to Europe to develop first dirigibles and rigid airships. His first airship, LZ 1, took its maiden flight in July 1900, and he followed it with ever larger airships that would eventually be capable of transatlantic flight. Zeppelins were used in combat during WWI and for intercontinental air travel during the interwar period, but their heyday ended in 1937 with the crash of the Hindenburg (LZ 129) and the advent of transatlantic airliners.

March 8, 1910 – Raymonde de Laroche becomes the world’s first woman to earn a pilot license. Born in 1882, de Laroche decided to become a pilot after seeing Wilbur Wright’s flying demonstration in 1908. The following year she convinced her friend and airplane manufacturer Charles Voisin to teach her to fly. Since Voisin’s aircraft had only one seat, her first flight was a solo covering some 300 yards and, one year later, de Laroche received license #36 from the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale. She made numerous flying demonstrations around Europe and Egypt and, despite serious injuries she sustained in a crash, she returned to the air and was awarded the Aero-Club of France’s Femina Cup for a four-hour nonstop flight. She also set two altitude records for women pilots in 1919. De Laroche died on July 18, 1919 in a crash that also killed her co-pilot.

March 8, 1909 – The birth of Beatrice “Tilly” Shilling, a British aeronautical engineer, motorcycle racer, and auto racer. Shilling is best known for her invention of the R.A.E. Restrictor, known to pilots as “Miss Shilling’s Orifice,” which helped eliminate the problem of engine flooding in the early Rolls-Royce Merlin engines used on the Hawker Hurricane and Supermarine Spitfire. Following the war, Shilling worked on the Blue Streak missile and investigated the effects of wet runways on aircraft braking. As a racer, she was awarded the Gold Star for lapping the Brooklands circuit at an average of 106 mph on her Norton M30 motorcycle, and refused to marry her fiancé until he matched the feat and earned a Gold Star of his own. Shilling died on November 18, 1990 at age 81.

Connecting Flights

If you enjoy these Aviation History posts, please let me know in the comments. And if you missed any of the past articles, you can find them all at Planelopnik History. You can also find more stories about aviation, aviators and airplane oddities at Wingspan.