Welcome to This Date in Aviation History, getting of you caught up on milestones, important historical events and people in aviation from June 17 through June 19.

June 17, 1959 – The first flight of the Dassault Mirage IV. The world entered the atomic age in 1945 when the United States dropped nuclear bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in the hopes that it would hasten the end of WWII. For a time, the US had a monopoly on nuclear weapons, but it wasn’t long before the Russians fielded an operational bomb of their own in 1949. The Soviets were quickly followed by England. But in the days before the first intercontinental ballistic missile, the only way to deliver a nuclear bomb to an enemy target was with a deep penetration bomber, one that could fly high and fast into enemy territory in the hopes of evading enemy interceptors and antiaircraft fire.

In 1954, French Prime Minister Pierre Mendès France decided that his country needed its own nuclear arsenal to put it on par with the United States, the Soviet Union, and Great Britain. France initiated development of a three-pronged nuclear deterrence (Force de frappe, later called Force de dissuasion) that would include land, sea, and air assets each capable of carrying out nuclear attacks. In 1957, work began on a supersonic bomber capable of carrying a nuclear weapon, and Dassault offered the Mirage IV, which was a substantially enlarged version of their single-engine Mirage IIIA fighter. Where the Mirage III was powered by a single engine, the Mirage IV was powered by two SNECMA Atar afterburning turbojets capable of pushing the bomber to a top speed of Mach 2.2. The wing surface was doubled over that of the fighter, and the wing was also made much thinner than the Mirage III for high-speed performance. It could be armed with either a single free-fall nuclear bomb, a single nuclear missile, or 16 conventional bombs. Though the Mirage IV carried three times more fuel than its predecessor, its armed range of 670 miles was still less than the Mirage III, and would have required multiple refuelings in the event that it had to reach deep inside the Soviet Union. And, if the nuclear mission had to be carried out, it would have been a one-way trip. The aircraft would not have had sufficient fuel to return, and even if it could, its home bases would likely have been annihilated.

The Mirage IV entered service in October 1964 as the first element of France’s nuclear triad, with 36 aircraft forming nine squadrons of four aircraft each. To carry out their missions, the Mirages worked in pairs, with one aircraft carrying a nuclear weapon while the other served as a tanker to refuel the attack aircraft. At the height of operations, there were always at least 12 aircraft in the air, with 12 more on the ground ready to deploy in four minutes should the need arise. The other twelve could be readied within 45 minutes. For seven years, the Mirage IV was France’s only means of delivering a nuclear weapon, as the land and sea components of the Force de dissuassion were not available until 1971. Dassault produced a total of 62 aircraft, and the Mirage IV served in the nuclear deterrence role until it was superseded by strategic nuclear missiles. The bomber variants were retired in 1996, though the reconnaissance versions served until 2005.

June 18, 1981 – The first flight of the Lockheed F-117 Nighthawk. Though the Nighthawk is very much a product of 20th century technology, the radar detection it was meant to avoid traces its history back to a time 100 years earlier. In 1886, German physicist Heinrich Hertz (for whom the eponymous measure of frequency is named) discovered that radio waves could be reflected back from solid objects. In 1904, another German, the inventor Christian Hülsmeyer, found a way to use radio waves to detect metal objects. By WWII, radar (which is actually an acronym for radio detection and ranging) was used by the British Royal Air Force to detect incoming German bombers, and radars were installed on aircraft to direct bombers to targets and to create the first night fighters. Following the war, development of radar technology made the sets ever more powerful, with increased range and the ability to track ever smaller targets. But what if you could make an aircraft that was invisible to radar, or at least one that had a radar cross-section (RCS) so small that a large aircraft appeared the size of a small bird? While not truly invisible, it would be impossible to detect the aircraft out of all the other normal clutter on a radar screen.

The idea that an aircraft might be made nearly invisible to radar was first proposed by Russian mathematician Pyotr Ufimtsev in 1964, though the shapes necessary rendered the concept impossible at the time because the aircraft would be unflyable. It wasn’t until fly-by-wire flight control computers became more sophisticated that the idea could finally become a reality. The Nighthawk program began with work led by engineer Ben Rich at Lockheed’s Skunk Works on a technology demonstrator known as the Hopeless Diamond, a nickname derived from the shape of the aircraft because nobody believed it would ever fly. On paper, Lockheed engineers believed that the new design would be 1,000 times less visible than any other aircraft ever created at Lockheed, and would show up on a radar screen as an object about the size of a marble. In 1976, the Air Force awarded a contract to develop the Have Blue project, the stealth demonstrator that proved the concept and eventually led to development of the F-117 Nighthawk.

The Nighthawk is instantly recognizable by its faceted shape, a series of flat surfaces that never join at a right angle. This myriad of differently angled flat surfaces works to reflect radar energy away from, rather than back to, the radar receiver. Special radar-absorbent coatings are also used to keep the radar signals from bouncing off the aircraft. But radar isn’t the only way to track an aircraft. The heat signature from jet engines is also easily detectable, so the Nighthawk’s engines are buried deep within the aircraft. This placement, however, ruled out the use of afterburners and limited the Nighthhawk to subsonic speeds. The F-117 also relied on redundant, fly-by-wire flight controls that make thousands of corrections per second. Without this system, the aircraft would simply tumble out of control.

Though given the “F” designation for fighter, the Nighthawk was strictly an attack platform for dropping guided bombs or missiles, and has no gun, either internal or external. After being revealed to the public in 1988, the F-117 made its combat debut in 1989 during the US invasion of Panama. Nighthawks saw extensive action in the 1991 Gulf War, where they flew the first missions of the war to knock out Iraqi radar sites and eventually took part in nearly 1,400 sorties. Though a number of Nighthawks have been lost to accidents, only one was ever lost in combat when it was shot down in 1999 during NATO operations over Serbia. Despite the F-117's stealthy design, Russian radar operators, using modified radars, discovered they could detect the Nighthawk when its landing gear or bomb bay doors were open. The plane came down relatively intact, and the Serbians invited the Russians and Chinese to inspect the wreckage and gain valuable information on American stealth technology.

Lockheed produced a total of 64 Nighthawks, and the F-117 was officially retired in 2008. However, observers have reported continuing flights of F-117s over the US Air Force’s super-secret testing site at Groom Lake in Nevada, popularly known as Area 51, and even more public sightings have occurred over the West Coast of the US. No official explanation has been given for the flights, but it is likely that the Nighthawks are playing the role of stealthy adversaries for Air Force and/or Navy flight training.

June 19-20, 1944 – The Battle of the Philippine Sea. The use of the airplane in warfare began in WWI, and by WWII it had become a formidable weapon. The Japanese demonstrated the enormous power of carrier-based warplanes with the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, and the ensuing Battle of the Coral Sea and Battle of Midway showed that the airplane had replaced the battleship as the center of power in the modern naval battle group. In both battles, no two surface ships ever fired a shot at each other, and Midway proved to be a turning point in the Pacific War, with a decisive American victory finally putting the brakes on what had been a relentless Japanese advance. Though they lost four carriers at Midway, Japanese naval aviation wasn’t utterly destroyed, though it was severely hobbled. There remained one more epic carrier battle to be fought. Coming two years after the pivotal Battle of Midway, the Battle of the Philippine Sea, the largest carrier battle in history, proved to be the last gasp for Japanese naval air power in WWII.

In the summer of 1944, American forces launched their island hopping campaign to take the Japanese-held islands of Tinian, Saipan, and Guam in the Mariana Islands. The Japanese, despite their losses at Midway, were still able to assemble a fleet that included five heavy carriers, four light carriers, five battleships, 11 heavy cruisers, two light cruisers, and 28 destroyers to contest the American advance toward the Japanese homeland. To counter the Japanese fleet, the Americans had Task Force 58, one of the most powerful armadas ever assembled. Under the command of Admiral Marc Mitscher, TF 58 included seven heavy carriers, eight escort carriers, seven battleships, eight heavy cruisers, 13 light cruisers and 69 destroyers. On June 16, a US submarine discovered the Japanese fleet off the coast of the Philippines as they turned to face the Americans. Mitscher divided his fleet into four carrier task groups and one battleship task group, while the Japanese divided their fleet into four groups based around their carriers.

Japanese scout planes spotted the American fleet on the morning of June 19 and launched the first attack. However, American radar detected the planes 50 miles away from the fleet, and American fighters were waiting for them when they arrived. In the ensuing battle, more than 200 Japanese planes were shot down against the loss of only 23 US aircraft. Meanwhile, US submarines had located the main body of the Japanese fleet. First, the carrier Taihō was struck with torpedoes, and then the carrier Shōkaku, which sank four hours later. The Japanese attacked again, but the planes flew in the wrong direction. Nevertheless, the attackers were detected and annihilated by American fighters.

By the end of the battle on June 20, roughly 600 Japanese aircraft had been destroyed, earning the battle the nickname “The Great Marianas Turkey Shoot.” Along with the huge loss of aircraft, the Japanese Navy lost three carriers and an estimated 3,000 dead. The Americans suffered one damaged battleship, 123 aircraft lost, and 109 dead. Though it might have been possible for the Japanese to replace their aircraft, the losses in experienced pilots was a blow from which they would never recover. Even though Japan still had carriers, they no longer had the men or planes to operate effectively from their decks, and the once-proud ships were reduced to the role of a diversionary force four months later in the Battle of Leyte Gulf, which resulted in another decisive victory for the US and her allies.

Short Takeoff

June 17, 1986 – The final flight of the Boeing B-47 Stratojet. When the final Boeing B-47 Stratojet (52-0166) was restored to flying status for a one-time ferry flight from Naval Weapons Center China Lake to Castle Air Force Base in California for museum display, it marked the end of one of the most influential designs of the early jet era. Following a 1944 US Air Force request for a new jet-powered bomber, the B-47 entered service with the Strategic Air Command in 1951. By 1956, there were 28 wings of B-47 bombers and five wings of RB-47 reconnaissance variants, with many staged at forward bases as part of America’s nuclear deterrence policy. Though the Stratojet never saw combat, it remained the mainstay of SAC’s bomber force into the 1960s. Over 2,000 were produced, and the EB-47E electronic countermeasures variant served until 1977.

June 17, 1961 – The first flight of the HAL HF-24 Marut (Spirit of the Tempest), a twin-engine fighter bomber designed by former Focke-Wulf designer Kurt Tank and the first jet aircraft developed and built in India. Though designed for Mach 2 flight, the lack of a sufficiently powerful engine meant that the Marut could barely reach Mach 1, and following the successful detonation of India’s first nuclear bomb, import restrictions prevented more powerful engines from being fitted. The Marut did see some action as a ground attack aircraft, and during the Indo-Pakistan War of 1971, an Indian pilot flying an HF-24 claimed a victory over a Pakistani North American F-86 Sabre. A total of 147 Maruts were built, and the type was retired in 1985.

June 17, 1955 – The first flight of the Tupolev Tu-104, (NATO reporting name Camel), the world’s first successful jet-powered airliner. Though the de Havilland Comet had flown first, the Comet was withdrawn from service in 1954 due to a series of fatal crashes and did not return to service until 1958. Tupolev based the Tu-1o4 on the Tu-16 bomber, and when the Tu-104 arrived in London in 1956 it caused much consternation in the West because nobody believed that the Soviets had the technology to produce a modern airliner. The Tu-104 entered service with Czechoslovak Airlines in 1957, and while it had a safety record comparable to other airliners of the time, a series of crashes led to its retirement on commercial routes in 1979, and it was removed from military service the following year.

June 17, 1928 – Amelia Earhart becomes the first woman to cross the Atlantic Ocean in an airplane. Though best known for her disappearance while attempting a circumnavigation of the globe in 1937, Earhart made headlines in 1928 as the first woman to cross the Atlantic Ocean in an airplane, though she did so as a passenger. In response to Charles Lindbergh’s famous crossing the previous year, Earhart accompanied pilot Wilmer Stutz and copilot/mechanic Louis Gordon on a 22-hour flight from Newfoundland eastward to Wales flying a Fokker F.VII trimotor. Since the flight was made on instruments, Earhart never did any flying during the trip, though on landing, she did tell an interviewer, “...maybe someday I’ll try it alone.” Earhart made her own solo Atlantic crossing in 1932.

June 18, 1983 – Sally Ride becomes the first American woman to fly in space. Ride joined NASA in 1978 and went to space in 1983 as a Mission Specialist on board Space Shuttle Challenger on STS-7, 20 years after the first woman in space, cosmonaut Valentina Tereshkova. At age 32, Ride was also the youngest American and the first LGBT astronaut to fly in space. She went to space a second time the following year, again on Challenger, as a Mission Specialist on ST-41-G. Ride left NASA in 1987, but served on the investigation committees into the Challenger and Columbia disasters. After teaching physics at the University of California, San Diego, Ride died of pancreatic cancer in 2012 at age 61.

June 18, 1928 – Explorer Roald Amundsen and his crew disappear in the Arctic. Roald Amundsen was a famed explorer of the Earth’s polar regions and became the first to reach the South Pole in 1911. On May 25, 1928 the airship Italia crashed in the Arctic Ocean while flying around the North Pole, and Amundsen and his crew of five left Tromsø, Norway in a Latham 47 floatplane to search for survivors. Flying across the Barents Sea, the aircraft disappeared without a trace. Two months later a piece of a float was found washed ashore, then three months later a gas tank washed ashore. The bodies of Amundsen and his crew were never found.

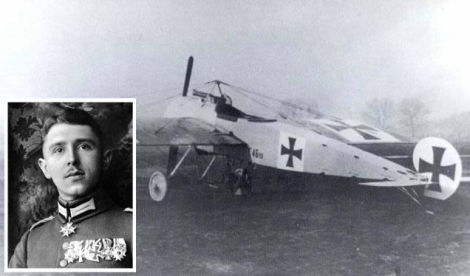

June 18, 1916 – The death of Max Immelmann. Immelmann was the first German ace of WWI, and the first to be awarded the Pour le Mérite, one of the highest awards of the Kingdom of Prussia. He is credited with the creation of the turning maneuver that bears his name, and had scored 15 victories by the time of his death. Immelmann was one of the first to make use of the interrupter gear developed by Anthony Fokker which allowed the pilot to fire directly through the arc of the fighter’s propeller. Ironically, Immelmann’s death resulted from a malfunction of the device, when he shot away the propeller of his Fokker E.III Eindecker monoplane and crashed.

June 19, 2002 – Adventurer Steve Fossett takes off on the first solo balloon circumnavigation of the Earth. Fossett departed from Northam, Western Australia on June 19 in a balloon named Spirit of Freedom, and flew eastward across the Pacific Ocean, over Chile and Argentina, then across the southern Atlantic Ocean to South Africa and then across the southern Indian Ocean, arriving back in Australia on July 4. The flight covered 20,626 miles and set numerous distance and flight longevity records. Fossett made other world record flights, including the first solo, nonstop circumnavigation of the Earth in the Virgin Atlantic GlobalFlyer. Fossett died in the crash of his private plane on September 3, 2007.

Connecting Flights

If you enjoy these Aviation History posts, please let me know in the comments. You can find more posts about aviation history, aviators, and aviation oddities at Wingspan.