Welcome to This Date in Aviation History, getting of you caught up on milestones, important historical events and people in aviation from October 14 through October 16.

October 14, 1964 – The first flight of the Sikorsky CH-53 Sea Stallion. When the operational jet engined debuted during the Second World War, it not only revolutionized fixed wing aviation, but also had a profound effect on the development of helicopters after the war, as the turbine engine offered greater power and speed over its piston-powered predecessors. In 1960, both the US Army and US Marine Corps began searching for a heavy lift helicopter to replace the CH-37 Mojave/HR2S, and the Army eventually settled on the tandem-rotor, turbine-powered Boeing CH-47 Chinook. In 1962, the US Navy issued a request for a Heavy Helicopter Experimental (HHX), a helicopter that could lift up to 8,000 pounds, have an operational radius of 100 nautical miles, and a speed of 170 mph. In order to save money, Defense Secretary Robert McNamara, who had built a reputation for trying to get different branches of the military to adopt the same aircraft to reduce costs, pressured the Marine Corps to adopt the Chinook. But the Marines argued that their requirements were significantly different from those of the Army. In particular, they expressed the need for a watertight hull, and they preferred to accept the offering from Sikorsky, which was basically an enlarged version of the S-61R.

After an intense competition, the Marines selected the YCH-53 over the Chinook, announcing in 1962 that it would procure two prototypes for further testing. (The US Air Force later adopted the CH-53 as the HH-53 Super Jolly Green Giant for combat search and rescue). The CH-53 had a six-bladed main rotor that was borrowed from the Sikorsky S-64 Skycrane (CH-54 Tarhe), a watertight hull that, while not intended for amphibious operations, allowed emergency landings on water, and was powered by a pair of General Electric T64 turboshaft engines mounted on pods outside the aircraft. Successively more powerful engines were added as development of the helicopter continued. The Sea Stallion had a crew of four and, depending on the mission, could carry 38 troops, or 24 stretchers with attendants, or an internal cargo payload of 8,000 pounds. An external load of 13,000 pounds could be slung underneath the aircraft.

The CH-53 saw immediate action in the Vietnam War, where it played a vital role in troop and materiel transport, as well as search and rescue. At the end of America’s involvement in the war, the size of the Sea Stallion aided tremendously in the evacuation of troops and civilians from Saigon as part of Operation Frequent Wind. The Sea Stallion continued to prove its mettle in every conflict since Vietnam, but was finally retired in 2012 after service in Afghanistan in favor of the CH-53E Super Stallion, a significantly upgraded and modernized version of the heavy lifter that benefits from the addition of a third turboshaft engine.

October 14, 1947 – Chuck Yeager breaks the sound barrier in the Bell X-1. On December 17, 1903, the Wright Brothers made their historic First Flight. Taking off from the dunes of Kitty Hawk, NC, the Wright Flyer covered a distance 120 feet at a speed of 6.8 mph, and since that momentous date, aircraft development has been driven largely by a quest for ever greater speed. But when the world entered the age of jet- and rocket-powered flight during WWII, the last great achievement of speed, Mach 1, about 765 mph depending on altitude and conditions, had yet to be reached.

Flying beyond the speed of sound is commonplace today, but supersonic flight in the mid-1940s was entirely uncharted territory. During the war, rocket planes and airplanes in a steep dive had come close, entering the realm of transonic flight, where they discovered that shockwaves along the wings severely inhibited the ability of the control surfaces to move, and could even cause control inputs to reverse. Some German pilots laid claim to breaking the sound barrier in the Messerschmitt Me 163 Komet rocket plane, but it was the British who made the first dedicated attempts at supersonic flight with the turbojet-powered Miles M.52. An extremely advanced aircraft for its time, the M.52 attempted to solve the controllability problems by pioneering the use of a powered stabilator, or flying tail, in which the entire horizontal tailplane moved, rather than just the elevators on the trailing edge of the tail of the horizontal stabilizer. Though the project was ultimately canceled before any aircraft were built, much of the Miles’ groundbreaking research in supersonic aerodynamics found its way to Bell as part of an agreement to share technical data on high-speed flight.

Bell had already begun work on a supersonic rocket plane, but the conventional tail they used suffered from the problems of compressibility at transonic speeds. With the data from the M.52 in their hands, Bell adopted the all-moving powered stabilator and the thorny control problem was solved. Unlike the M.52, was powered by a turbojet, the X-1 was powered by a four-chamber Reaction Motors liquid fuel rocket. Each chamber provided 1,500 lbf of thrust, and the chambers were lit in succession to accelerate the aircraft.

The X-1's maiden flight, a gliding test in Florida, took place on January 25, 1946. After more successful glide tests, the X-1 was taken to Muroc Army Air Field in California, modern day Edwards Air Force Base, for powered tests. Bell chief test pilot Jack Woolams, who flew all the glide tests, had died on August 30, 1946 while practicing for the National Air Races in Cleveland, and another Bell test pilot, Chalmers “Slick” Goodlin, demanded $150,000, the equivalent of about $1.6 million today, to make the flight. So the controls passed to Chuck Yeager.

Yeager had begun his military career as an enlisted aircraft mechanic before training as a pilot, and he became an ace while flying the North American P-51 Mustang in WWII. Yeager continued his career after the war as a test pilot. Two days before the historic flight, Yeager broke two ribs in a horse riding accident, but he hid the injury from the Air Force so he wouldn’t be barred from flying. The pain from the injury made it impossible for him to close the hatch on the X-1, so fellow pilot Jack Ridley rigged a broom handle to the door to allow Yeager to close it. Yeager nicknamed the bright orange X-1 Glamorous Glennis after his wife, the same name he had given his Mustang.

On October 14, 1947, Yeager and the X-1 were taken aloft by a modified Boeing B-29 Superfortress and dropped over the dry lake bed. Yeager fired the rocket engine after falling clear of the B-29 and accelerated the X-1 to a speed of Mach 1.07 at 45,000 feet, thus becoming the first plane and pilot to break the speed of sound in level flight. After the rocket fuel was expended, the X-1 glided to a soft landing on Muroc’s the lake bed. For his historic flight, Yeager was awarded both the Mackay and Collier Trophies in 1948, and he received the Harmon International Trophy in 1954. After his historic flight, Yeager continued to set more speed records, and held various Air Force commands before retiring at the rank of brigadier general. The Glamorous Glennis now resides at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington DC.

Not only was the data gleaned from the X-1 flights used in future X planes and supersonic aircraft, the entire test and evaluation program served as a model for all future X plane projects. The pioneering work done by Bell and NACA (the precursor to NASA) has led to aircraft such as the Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird which routinely flew at three times the speed of sound, and the experimental NASA X-43 hypersonic aircraft, which has reached speeds approaching Mach 10.

When Chuck Yeager pushed the X-1 past the sound barrier, a mere 44 years had passed since the Wright Brothers’ historic flight in the dunes of North Carolina. Orville Wright was still alive, though he died two months later. In a stunning testament to the rapid technological advances of the airplane in the quest for speed, the world had gone from the first flight to Mach 1 in the span of one man’s life.

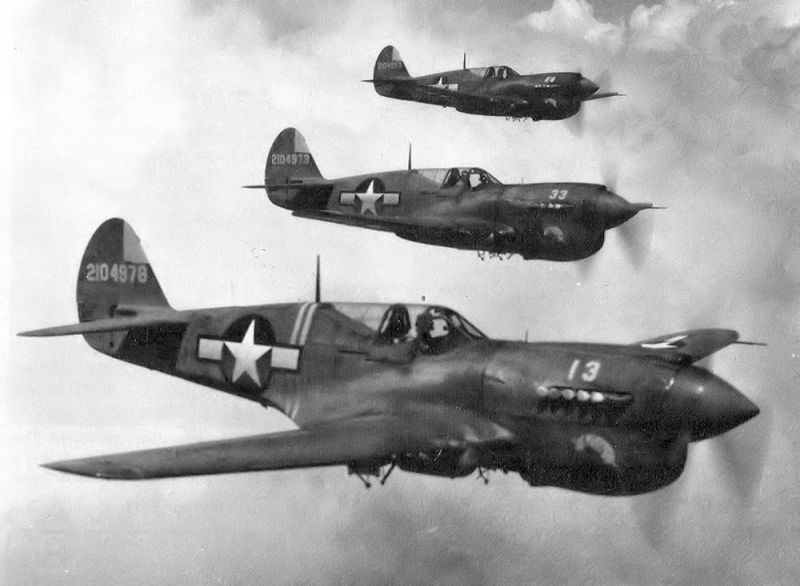

October 14, 1938 – The first flight of the Curtiss P-40 Warhawk. The Curtiss P-40 Warhawk has become one of the iconic aircraft of WWII, perhaps best known for its service with the 1st American Volunteer Group, popularly known as the Flying Tigers, fighting in China. Fighting to defend the Chinese Nationalist government from Japanese invasion, the Flying Tigers, in their classic shark-mouthed P-4os, outnumbered and outgunned, fought doggedly against more maneuverable Japanese aircraft. While the P-40 was neither the fastest nor the most nimble fighter of the war, it was one of the most numerous, and was available to America and her allies in large numbers before more powerful fighters could be brought to bear.

The Warhawk traces its roots back to the Curtiss P-36 Hawk, a fighter that was designed at the same time as the Messerschmitt Bf 109 and Hawker Hurricane. It proved popular with pilots, and though it saw limited action at the outbreak of WWII, the P-36 fought well for the French in the early years of the war. But while pilots appreciated good handling of the P-36, the fighter suffered from a serious lack of power. To address this deficiency, Curtiss began work on a more powerful fighter, and they started by modifying the tenth P-36A Hawk airframe. Rather than use the Pratt & Whitney R-1830 Twin Wasp radial of the P-36, Curtiss gave the Warhawk an Allison V-1710 V-12 engine, the only operational American-designed V-12 liquid-cooled engine developed by the US during the war, and the same engine found in the Lockheed P-38 Lightning and Bell P-39 Airacobra. At first, the original P-40 design called for the radiator to be placed behind the pilot, but the Curtiss-Wright sales department asked that it be moved to the front, perhaps in an attempt to make the P-40 look more like its P-36 predecessor in hopes of making it more appealing to the Army. The radiator placement gave the P-40 its iconic shark mouth silhouette, and the rear-mounted radiator later became the trademark of another famous fighter, the North American P-51 Mustang.

A major drawback for the new fighter, however, was its single-stage, single-speed supercharger. But what the Warhawk gave up in performance it made up for in ruggedness and firepower. The lack of engine power limited the Warhawk’s performance against more powerful German aircraft at high altitudes, but it more than held its own under 16,000 feet. And while more nimble aircraft, such as the Japanese Mitsubishi A6M Zero, could outmaneuver the Warhawk, the development of effective hit-and-run combat tactics gave it an edge against the more fragile Japanese designs.

The P-40 was developed into a myriad of variants, including the P-40F and P-40L, both of which mounted a Packard V-1650 Merlin V-12 in place of the Allison. But with the majority of the Merlin engines going to the P-51, Curtiss reverted to the Allison engine, and it was the P-40N that became the definitive model and was produced in the greatest numbers, with 5,220 of the nearly 14,000 fighters built as the P-40N. The N retained the stretched fuselage that was introduced with the F, and attempts were made to further lighten the aircraft by removing two of the six wing-mounted .50 caliber machine guns. But in practice, the added firepower was preferable to the increase in speed and the guns were replaced. The fuselage behind the pilot was opened up and covered with plexiglass to improve rearward visibility, and the rugged, powerful fighter was used primarily for ground attack from 1944 onward. The P-40 was the third most-produced American WWII fighter behind Republic P-47 Thunderbolt (15,660) and the P-51 Mustang (15,586). It was also exported to almost every Allied combatant in WWII, and found great success with the Royal Air Force and Royal Australian Air Force, where it was known as the Tomahawk and the Kittyhawk. Though built in large numbers, only about 28 Warhawks remain flying today, while many others are displayed in aviation museums around the world.

October 15, 1933 – The Rolls-Royce Merlin engine is started for the first time. Hurricane. Spitfire. Lancaster. Mosquito. Mustang. These are the names of some of the greatest aircraft to come out of WWII, and they all share one thing in common: the mighty Rolls-Royce Merlin 12-cylinder engine, one of the most successful aircraft piston engines ever produced. Work began on the the Merlin in the early 1930s when Rolls-Royce determined that they needed an engine that could provide more power than the 21-liter Kestrel engine then in production. The Kestrel had provided power for a great number of British and even German aircraft, though most of those types were obsolete by the outbreak of WWII.

The new 1,100 hp engine was called the PV-12, as it was a private venture that received no government funding for its development. At first, Rolls-Royce chose an evaporative cooling system for their new engine, but that arrangement was abandoned in favor of a more traditional liquid cooling system when the former proved to be unreliable, and ethylene glycol, which helps with the liquid cooling process, became available from the US. While the PV-12 was under development, the Air Ministry issued requirements for two new fighters, and both the Hawker Hurricane and Supermarine Spitfire were built around the new PV-12 rather than the older Kestrel.

In keeping with the tradition of naming their engines after birds of prey, the PV-12 was renamed for the Merlin, a small falcon known for its speed and agility. The Merlin was first mated to a Hawker Hart biplane for testing, but the first run of production engines was fraught with unreliability, such as cylinder head cracking, coolant leaks, and excessive wear to the camshafts and crankshaft main bearings. These problems were ironed out in the development process, and the Merlin II and Merlin III became the standard production engines. Development of a centrifugal supercharger progressed alongside engine development, and water injection further improved the engine’s high altitude performance. The Merlin was produced in England as well as under license by Packard in the US as the V-1650 Merlin. It would eventually be used to power 43 different aircraft, from single-engine fighters like the Spitfire and North American P-51 Mustang to large four-engine bombers such as the Avro Lancaster. Nearly 150,000 Merlins were built by the time production ended in 1950.

Short Takeoff

October 14, 2012 – Felix Baumgartner sets a new altitude record for a parachute jump. The jump was part of the Red Bull Stratos project which set out to break the existing parachute altitude record of 102,8oo ft set by US Air Force Capt. Joseph Kittinger during the US Air Force Excelsior project in 1960. Stepping out of a capsule suspended from a balloon, Baumgartner dove from an altitude of 128,097 feet and reached a speed of 1,357.64 mph in free fall, becoming the first person to break the speed of sound without a vehicle. Baumgartner’s record stood for just two years before it was broken by Google executive Alan Eustace, who jumped from 135,890 feet.

October 14, 1962 – A US Air Force Lockheed U-2 reconnaissance flight over Cuba discovers Russian-built ballistic missile launching facilities, triggering the Cuban Missile Crisis. Following the failed Bay of Pigs Invasion in 1961 and the installation of American missiles in Italy and Turkey, the Cuban Revolutionary government requested that the Soviets place missiles in Cuba to deter any more American action against the Communist island nation. The US demanded that the R-14 Chusovaya medium-range nuclear missiles be removed and, after a tense 13-day stand off highlighted by low-level US reconnaissance flights over Cuba and an American naval blockade of the island that put the world on the brink of nuclear war, the Russians backed down and agreed to dismantle the sites and remove the missiles.

October 14, 1953 – The first flight of the North American X-10, an unmanned aircraft powered by two Westinghouse J40 turbojets and designed to investigate the feasibility of long-range cruise missiles. Though essentially a flying missile, the X-10 was fitted with landing gear which made the aircraft reusable. It had a delta wing and forward canard, and was controlled in flight by an onboard computer. When the X-10 entered service for testing, it was the fastest turbojet-powered aircraft of its day. With a maximum speed of Mach 2, the X-10 could reach an altitude of 49,000 feet and had a range of 627 miles. Thirteen research aircraft were built, though only one survives, and it is housed at the National Museum of the United States Air Force in Ohio.

October 14, 1949 – The first flight of the Fairchild C-123 Provider, a transport and cargo aircraft designed by Chase Aircraft and built by Fairchild Aircraft. The C-123 was originally designed by Chase as an airborne assault glider before the addition of two Pratt & Whitney R-2800 radial engines which were later augmented by two General Electric J85 turbojets. The C-123 primarily served the US Air Force before being transferred to the US Coast Guard, Air Force Reserve and Air National Guard, and saw extensive use in the Vietnam War, most famously—or notoriously—as the platform used to spray Agent Orange defoliant. Just over 300 were built, and the type was retired in 1980.

October 14, 1943 – Bombers of the US Eighth Air Force attack the ball bearing factories at Schweinfurt for a second time, suffering heavy losses. Strategic bombing in WWII was seen as a way to destroy both enemy war production and morale, and the ball bearing factories at Schweinfurt were seen as a “panacea target” whose destruction might cripple the German war machine. Following an unsuccessful raid on the factories in August 1943, 291 Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses tried again, but more than 1,000 Luftwaffe fighters rose to meet them. The ensuing carnage came to be known as Black Thursday. Republic P-47 Thunderbolt escort planes ran short of fuel, leaving the bombers to continue to the target unescorted. By the end of the mission, 198 of the 291 bombers were either damaged or destroyed, and 650 airmen had been killed, wounded, or listed as missing in action. The raid was ultimately a failure, as ball bearing production was not halted, and it would be four months before the Allies tried again, but with more effective long-range escort provided by the North American P-51 Mustang.

October 15, 1985 – The first flight of the Fairchild T-46 Eaglet, a proposed primary jet trainer developed in response to the US Air Force’s Next Generation Trainer program in 1981 to find a replacement for the Cessna T-37 Tweet. After construction by Burt Rutan of a 62% scale aircraft, the Air Force accepted the Eaglet and placed an order for 650 aircraft. However, despite the successful flight of the T-46, the cost of production had almost doubled, and budget cuts mandated by the Gramm-Rudman-Hollings Balanced Budget Act of 1985 led to the cancellation of the program after only three aircraft were built. The cancellation also meant the end of the storied Fairchild Aircraft company.

October 15, 1952 – The first flight of the Douglas X-3 Stiletto, an experimental aircraft that was designed to investigate sustained flight at supersonic speeds. It was hoped that the Stiletto would maintain speeds of Mach 2, but its Westinghouse J34 afterburning turbojets were so underpowered that it was unable to achieve Mach 1 in level flight, though it did go supersonic in a dive. Despite not reaching its goals, the program was still considered a success, as it provided significant data on fuselage strength necessary for high-speed flight over the course of 51 test flights, and data gleaned from the short, trapezoidal wings was used by Lockheed in their design of the F-104 Starfighter.

October 15, 1946 – The death of Hermann Göring. Born on January 12, 1893, Göring began his military career as a fighter pilot in WWI, where he became a fighter ace and was awarded the Pour le Mérite, also known as the Blue Max, one of the highest honors of the Kingdom of Prussia. Göring assisted Adolph Hitler in his rise to to power in 1933, formed the feared Geheime Staatspolizei (Gestapo) secret police, and became the second most powerful man in Germany. In 1935, Göring became commander-in-chief of the Luftwaffe, though his lack of success caused him to lose favor with Hitler. Göring eventually withdrew from positions of leadership to focus on looting artwork, and was tried after the war as a war criminal. Convicted and facing death by hanging, Göring committed suicide the night before the prosecution of his sentence by ingesting a cyanide capsule that had been smuggled to him by an American guard whom Göring had bribed.

October 16, 1956 – Pan Am Flight 6 ditches in the Pacific Ocean. Pan Am Flight 6 was a scheduled round-the-world flight that departed Philadelphia in a Douglas DC-6 flying eastward with stops in Europe and Asia. After a change of planes in Honolulu, Flight 6 then departed for San Francisco in a Boeing 377 Stratocruiser (N90943). Upon reaching 21,000 feet, the No. 1 engine entered an overspeed condition, followed by problems with engine No. 4. The captain decided that he would have to ditch in the Pacific Ocean, and rendezvoused with the USCGC Pontchartrain (WHEC-70) that was on station between Hawaii and California for just such an eventuality. The airliner circled the cutter until dawn to burn off fuel and make the ditching as safe as possible, then landed on a foam path laid out by the cutter. The tail of the aircraft broke off, but all 31 passengers and crew had moved to the front of the plane prior to ditching and were promptly rescued with only minor injuries. However, 44 cases of live canaries were lost in the cargo hold.

October 16, 1937 – The first flight of the Short Sunderland. One of the great flying boats to come out of the 1930s, the Short Sunderland was partially based on the Short Empire commercial airliner. The Sunderland was upgraded extensively for military service and became one of the most powerful and widely used flying boats of WWII. In wartime service, Sunderlands were primarily responsible for tracking and attacking enemy submarines, as well as rescuing victims of submarine attacks. It reportedly earned the nickname Fliegendes Stachelschwein (“Flying Porcupine”) from the Germans who faced her bristling defensive armament. After the war, Sunderlands saw service in the Korean War and the Berlin Airlift before the type was retired from military service in 1959. Remaining Sunderlands were converted to civilian use as the Short Sandringham, and flew into the 1970s. A total of 777 Sunderlands were produced between 1938 and 1946.

Connecting Flights

If you enjoy these Aviation History posts, please let me know in the comments. You can find more posts about aviation history, aviators, and aviation oddities at Wingspan.