The A stands for “alternate”.

US89A is a meandering, shoulderless, shimmering ribbon of indifferently maintained tarmac that traverses some of the most striking country in the Lower 48.

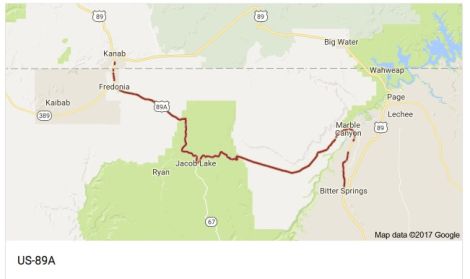

Rolling south from Kanab, Utah, and ending 92 miles later at Bitter Springs on the Navajo Nation, US89A used to be the primary highway linking Flagstaff and Page, Arizona to southern Utah. In many places, US89A feels like it has no destination at all. It encourages you to see the road for itself, not for where it is taking you, which is a wonderful thing.

In 1960, a new section of highway, which would become US89, was completed further north - wider, faster, straighter, more efficient. The original road was relegated to “alternate” status. To me this is a very distinctly American thing to do. Having a perfectly serviceable and very nice highway, somebody looked at the map and said, “Well fellas, I think we need another one right next door. Get to it.”

Why? Because we could. Because nobody builds roads like Americans. Because Americans are always looking to the future. Because we can’t help it.

On the eve of my departure for Africa, I’ve been feeling nostalgic, and more than a little bit wistful about this crazy, wonderful, frustrating, incredible thing we call “America”.

I had been itching all spring to hit the road. The winter this year in Montana never seemed to end, and I hadn’t seen the desert in nearly a year. I wanted to get out, to be drawn into the sand and the hard light. To take the back roads and find the lonely places, both new and familiar. To find what the French philosopher Jean Baudrillard, in his slim travel memoir America, calls “astral America” - the America of the stars:

I went in search of astral America, not social and cultural America, but the America of the empty, absolute freedom of the freeways, not the America of mores and mentalities, but the America of desert speed, of motels and mineral surfaces.

I wanted to see astral America, an alternate America.

So the second week of May I loaded up the Jeep, queued up a few hours worth of Magnolia Electric Co., Warren Zevon, and Willie Nelson, and set the compass south for Arizona, and Overland Expo West.

This trip is documented in three parts: part one, the mad hammer-down 1000 mile dash I made in two days to get to Flagstaff, and parts two and three, the more deliberate and dusty return trip through Utah back to Montana.

(You can read more about OvEx West in my previous post, as well as Tim’s and Tyler’s. Get comfy. This may surpass even a Rufant-length trip report, and it is heavy on the photos - all taken on my phone. I had originally planned to do this in two parts, maybe three, but I managed to upload all the photos at once, so I said “screw it”, and it’s all here.

Here’s a playlist that matched my mood on this trip to accompany your read, if you’re so inclined. RIP Jason Molina.)

Part 1: Speed and Distance in America

I hit the road mid-week (and later than I wanted) on a diamond-perfect day that makes you wonder why you would ever leave Montana in the first place. But also a day that rewards your decision to take the wheel and pile on the miles.

A few things I saw as I ate up the interstate in Montana, Idaho, and Utah:

- An absolutely pristine Nissan Hardbody pickup in Rod Millen livery.

- A herd of Tibetan Yaks browsing the spring green hills near Drummond, Montana.

- A tall hitchhiker in a Stetson and a crisp snap-button shirt thumbing a ride outside Deer Lodge, Montana. I almost stopped. Almost. (This was a poor decision on his part, given that Deer Lodge is Montana’s prison town, but when you’re hitching, you have to take what you can get, I suppose.)

- A murdered-out Hummer H1 with Oregon tags on a flatbed trailer, towed by a Hummer H2.

- Two busloads of gregarious Chinese tourists in eastern Idaho, giving me a wave and the thumbs up at the gas station.

- A large Muslim family, the women in brightly colored hijabs, buying Dr. Pepper and beef jerky at the convenience store in Nephi, Utah.

- Me, yelling obscenities at Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke who was interviewed on the radio during his visit to the Utah National Monuments.

I managed to hit Salt Lake City right about rush hour due to my late start and a lot of road construction in Idaho, but the traffic wasn’t terrible, and soon I cleared the congestion and was flying south again.

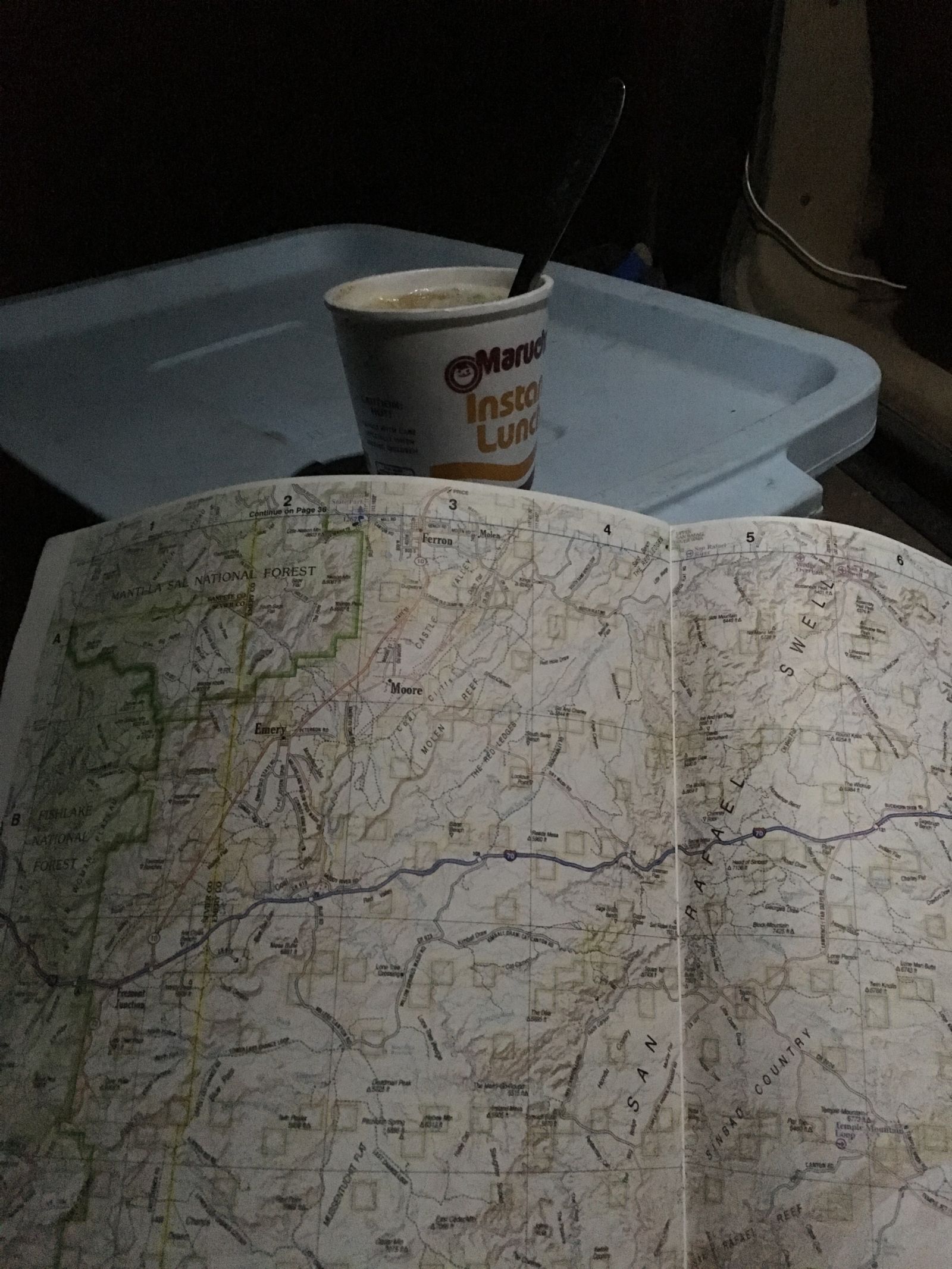

But with two-thirds of Utah dispatched, daylight was running low and I was getting road-weary, so a camping spot was in order. I pulled over to scan the atlas for public lands with promising options and zeroed in on a US Forest Service access road about 15 miles east of the highway near Kanosh, Utah.

This was the Fishlake National Forest and it felt good to put wheels to dirt after a long day on the super slab. Not wanting to spend a lot of time hunting down a good campsite with darkness closing in, I had identified a formally designated campground as my best option.

Unfortunately, the self-pay kiosk at the campground was asking $12 for a campsite, and I only had $50's (Like, three of them. That’s how I roll). I was not about to leave a $38 tip to the Forest Service no matter how much I like them, so I backtracked a few miles and found a dispersed campsite in a secluded grove of elm and cottonwood trees by the north fork of Corn Creek. I was completely alone.

I finally switched off the Jeep as night fell. The creek was running high, and it made a pleasant, soothing sound, not unlike the rumble of my A/Ts on the highway, but far more relaxing. I slurped noodles from a styrofoam cup and studied some options for my return trip that would take me to more secluded spots like this one.

I woke the next morning before the sun came up, and got to work brewing coffee and folding up the tent. As the first rays of sunlight spilled over the ridge immediately to the east, I finally got a decent look at my impromptu campsite.

Not bad.

But there wasn’t much time to linger - I needed to be in Flagstaff close to noon to register and guarantee a decent campsite at Overland Expo, so I turned south again and joined the long-haul truckers chasing the sunrise on I-15.

As I drove along, I began to see them: overlanders.

I had passed a handful the day before, all decked out in roof-top tents, off-road trailers, and Hi-Lifts, or riders leathered-up on dual-sports. But as I got closer to Arizona, they began to multiply, merging together from all directions.

They were all clearly headed to Flagstaff, but in their haste or laziness most had camped the previous night just off the highway in the barrow pits and gritty turn-outs.

I was feeling pretty smug since I had managed to find a genuinely wonderful campsite in the woods, and I was awake and on my way well before the others scattered haphazardly across the interstate exits. Amateurs.

Onward. Utah State Highway 20 connects I-15 to US89 in the Panguitch Valley - which would take me all the way to Flagstaff. It climbs steeply into the Tushar Mountains, the pass topping out at nearly 8000 feet. As I pulled into the lookout at the summit, the grand diversity of Utah landscapes stretched out far below me, and, also... some clouds that had well and truly lost their way?

The valley appeared to be completely socked in.

I laughed out loud at the absurd shift in the weather - this was genuine pea soup, where just minutes before the sun was burning a lopsided tan on my left arm dangling out the driver’s window. I dropped my speed as I wound down the thousands of feet on the far side of the pass and hoped that it would burn off soon. I hated to miss any of the scenery, but I appreciated the novelty of parting the clouds at ground level.

And burn off it did - just north of Kanab, Utah near Coral Pink Sand Dunes State Park. I idled into Kanab, filled the tank with 89 octane and the cooler with ice and beer, and had a decision to make - US89 via Glen Canyon, and Page, Arizona, or the old highway, US89A through the Vermillion Cliffs and the Navajo Nation?

Alternate America.

US89A is a mesmerizing combination of twisty, broken pavement at high altitude among Ponderosa pines and fire-scorched forests, vistas almost too far and stunning to fully comprehend, and hypnotizing straights that invite foot-to-the-floor flirtations with danger and oblivion.

The speed in particular draws you in – the 4.0 in the XJ has a sweet spot in the powerband just north of 2500 rpm, right about where it sits at 80mph in top gear. So if you’re tempted to lay on the throttle, you can produce downshifts and speeds upward of 90mph very quickly before smacking into the aerodynamic limits of the box. It’s tempting, but not really warranted, especially in a land with no shoulders and little margin for error.

Jean Baudrillard again:

Speed is the triumph of effect over cause ... Speed creates a space of initiation which may be lethal; its only rule is to leave no trace behind. ... Driving like this produces a kind of invisibility ... [i]t is a sort of slow-motion suicide. ...

Driving is a spectacular form of amnesia. Everything is to be discovered, everything to be obliterated.

Here is the conflict I grapple with on highways like this. I am torn between pure speed - which the road and the landscape invite - and taking my time to see and feel the experience more carefully.

For me, all too often, the speed wins. That interesting historical marker? Yeah, it’s history. That scenic overlook? Overlooked.

For the many abandoned Navajo craft shops that line the shoulders on US89A - dusty, ramshackle lean-tos - the speed has been too much for them, too. Most are now vacated, their proprietors and wares swept up by the gift shops and ignored by the tourists (like me) roaring by at 80mph, bent on discovery or amnesia.

But this was clearly a fat year.

The desert was green and lush, drawing stark contrasts with the high red cliffs and buff sands. Content calves, kids, and foals romped across the sage bottomlands. The cacti, creosote, and bunch grass were blooming, alive and well for that short time before the real heat arrived.

Even the strays were fat and happy.

Part 2: Paradise Canyon

A little while back, Rufant dubbed the XJ “The Golden Bullet”. I thought this was a good monicker for our Jeep, though, privately I had been calling him Hayduke for a some time. Hayduke the Golden Bullet it is.

George Hayduke famously plotted to sabotage Glen Canyon Dam in Edward Abbey’s novel The Monkey Wrench Gang, and even though Abbey is ambivalent about cars and the hordes of witless tourists they bring to the wild places in this country, he still has a soft spot for beat-up 4x4s, and I hoped the old XJ would pass muster with Rudolph the Red.

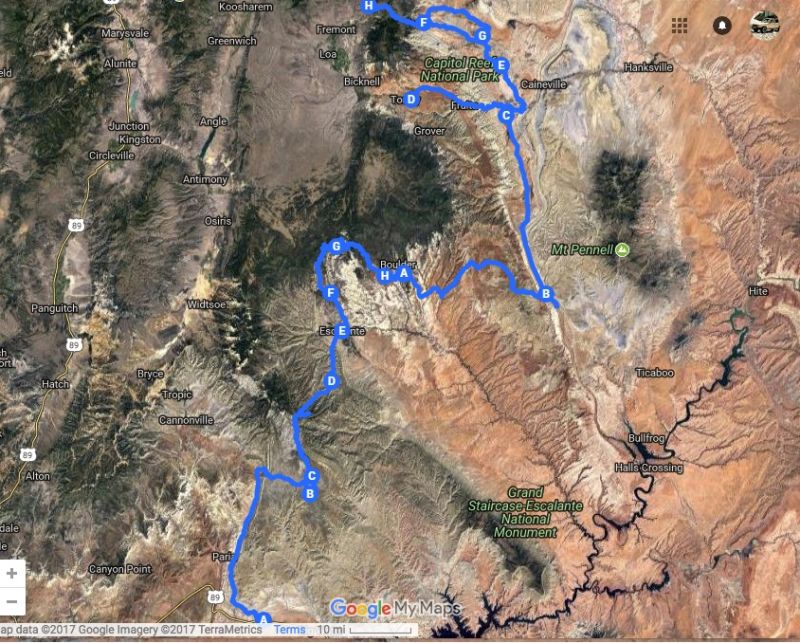

With Overland Expo winding down for me, and feeling impatient, I packed up quickly after my final class on Saturday morning. Inspired by tales of African deserts shared among my students, I felt the distinct pull of one of America’s great deserts just to the north. Keeping to US89 this time, the route would take me through Page, Arizona, west over the Colorado river at Glen Canyon, and into Utah’s Kaiparowits country.

My goal? Keep to the dirt and the solitude as much as I possibly could before I was forced home by time and obligation. I wasn’t entirely certain what the fuel situation would portend, so I stopped briefly at the Flagstaff WalMart for an $11 jerry can, filled up with fuel, restocked the cooler and laid rubber for Utah.

Here’s what I settled on with little to no information or objective other than my finger tracing the wisp-thin BLM roads on my DeLorme Atlas.

About 30 miles west of Page, and 45 minutes past some decidedly average Thai food, is a clearly marked turn-off for Cottonwood Canyon Road. This well-trod gravel two-track would take me north into Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument along the Cockscomb (where Hammerhead traveled last spring), and where I would decide my fate among the dozens of Bureau of Land Management roads that offered further adventures.

Needless to say, getting on the dirt, no matter how well maintained at first, put me in a different frame of mind. No more speed, no more amnesia - only discovery.

Nearly all the miles that lay ahead were new to me, and I had no agenda other than to find a good campsite. It was mid-afternoon, and even though the forecast called for high winds, the sun was shining and the road was empty.

As Cottonwood Canyon Road and Grand Staircase unwound under my Firestones, I paused at turn-outs along the banks of the espresso-muddy Paria River, and winced in shame when I thought I had murdered a 6-foot long rattlesnake basking in the road on a blind curve. Further inspection revealed it had been dead for some time, and a few more miles found me at the intersection for Grosvenor Arch.

The arch marked my decision point. A short drive west was Kodachrome Basin State Park, a hot shower, and a level campsite. But I had been to Kodachrome the year before, and paved roads lay that direction. So, with evening swiftly approaching I elected the dotted BLM road to the east, truly into the unknown, and I carried only the dim hope of stumbling on a decent place to rest my head.

One of the benefits of solo travel is the distinct lack of negotiation. The variables I weighed were mine and mine only, so the choice was a fast one. With the Jeep running cool and remarkably smooth, Hayduke only seemed to egg me on.

This is ridiculous anthropomorphism, but sometimes I swear this truck is happiest when we’re on the dirt in four-wheel drive and finding new adventures. It’s probably just projection.

Working my way east into more and more rough terrain, I finally turned due north onto the final leg of Paradise Canyon Road, and was greeted with stunning vistas and a discouraging sign.

Paradise Canyon Road follows the top of a hog-back ridge just west of its namesake, and the more famous Escalante Canyon and Collet Canyons. The views stretch both east and west from the ridge onto the endless sage plains.

I passed up several excellent campsites with stunning landscapes in all directions, but drawn by “around the corner fever” and with no schedule to speak of, I pressed on as the light continued to fade.

Soon, I dropped precipitously from the ridge into Paradise Canyon itself, and the going got much more tricky.

The road itself was not particularly onerous - except for some relatively steep sections, it was wide and mostly well-graded. I engaged low range only in a handful of places, mostly to take advantage of engine braking on downhills. But, the soft, silty soils that made up the road surface were clearly susceptible to erosion, and the wet spring had thrown some surprises in the mix. This road would be completely impassable in a rainstorm.

On off-camber corners, and in places where the road bottomed out across seasonal streams, the spring runoff had carved deep, narrow, and square-shaped channels across the track. Some were too deep to tackle head-on, and carefully angled approaches proved necessary. These obstacles seemed to get more difficult the further I progressed up the canyon, and the more the road narrowed and suffered from lack of maintenance.

In other words: perfect. And then:

This was clearly a problem. Maybe the sign had been right after all? In the photos above, in the upper right you can see an alternate route that someone had blazed before me on the downstream side of the bridge. But even that had been washed out below, and I didn’t feel comfortable tackling it alone, especially with the sun rapidly disappearing and my need for a decent campsite impending.

I shut off the engine, pondered my options for a moment, and backtracked on foot for a short distance. I noticed some faint tire tracks leading into the grass on the upstream side of the creek bisecting the road. Following them for a while revealed a crossing that looked doable, but would it rejoin the main road on the far side? Only one way to find out.

Having dispatched this obstacle, it was after 7:00pm and the dinner bell was ringing. But no obvious campsite revealed itself, and I resolved to put on a few more miles.

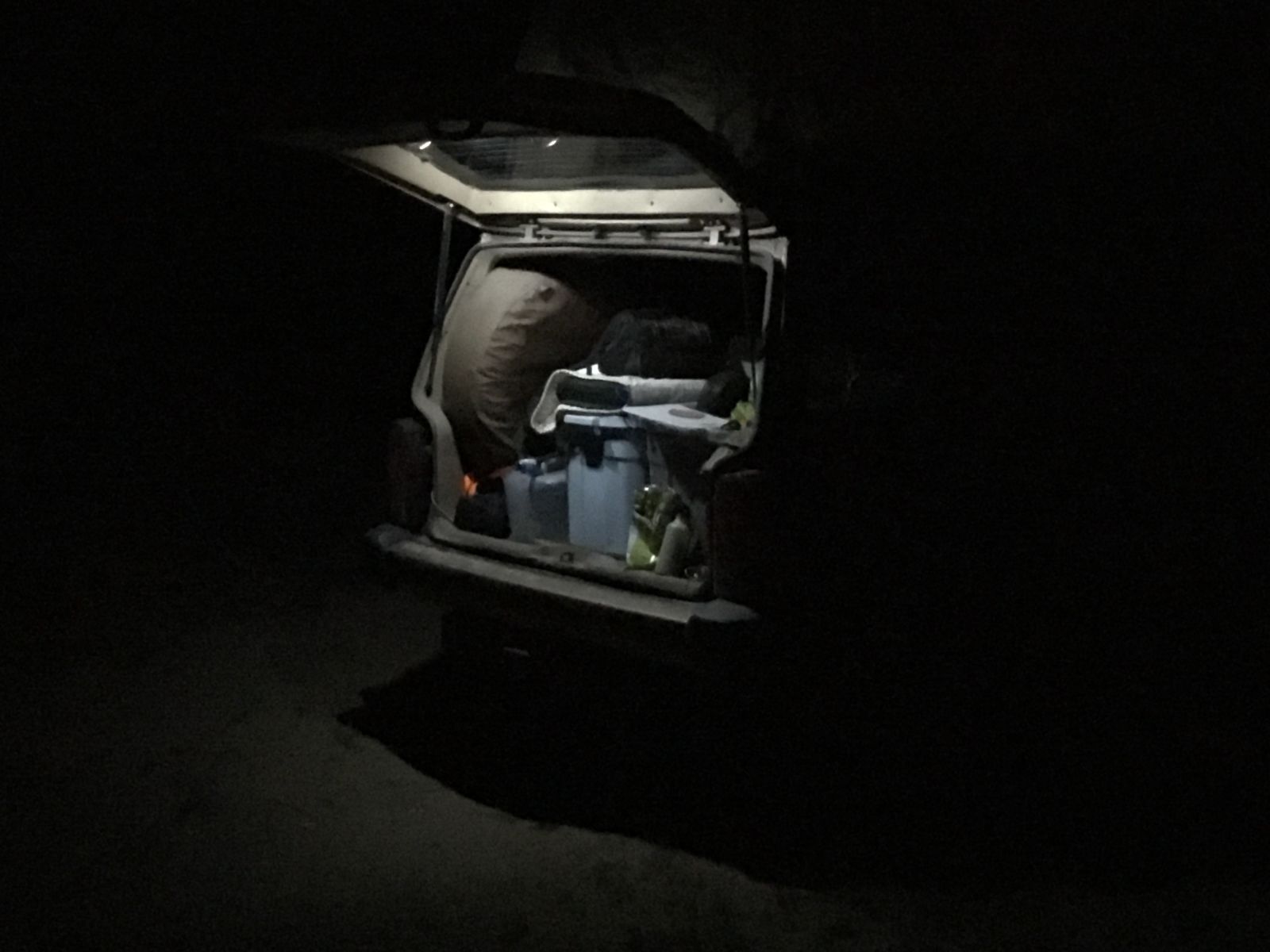

But as the road climbed slowly out of the headwaters of the canyon, it only narrowed, and convenient turn-outs were not to be found. I finally drove upon two different spur roads, but one only dead-ended in a grim, sandy wash (which nearly bogged me down as I tried to reverse out of it), and the other at a slimy stock watering tank. Neither felt “right”, so with increasing urgency I pressed on into the darkness.

Paradise Canyon Road finally descended off of Death Ridge (seriously) and intersected BLM Road #300 about 15 miles south of the town of Escalante, Utah. (Say it like the locals: “Escul-ant”.)

I was fighting cattle wandering across the road and definitely not finding my dream campsite. But it was now actually nighttime, so what did it really matter at this point? Feeling worn out and ready just to park in the flattest patch of sage I could find, I stumbled on a barely perceptible trail leading off into the pitch-black. I thought, “I’ll explore this one last track, and if it doesn’t turn out, I’ll give up.”

When a fire ring and a level parking spot materialized in my headlights, I thankfully shut down the XJ and broke out the hatchet and the firewood. A ham sandwich and two beers later, I felt much better.

Part 3: Into the Slanted Lands

My private nickname for Utah is “The Slanted Lands”. Everything seems just a little tilted, angled on a different plane.

Capitol Reef National Park is the poster child for this wonderfully disorienting axial shift, and I was headed there on my next-to-last day on the road. For the second night on this trip, I had driven myself into a situation where I was forced to grope around in the dark for a campsite; and for the second time, morning revealed a pretty magnificent result.

Again, there was little time to linger over lazy cups of coffee - I was determined to score a good campsite in Capitol Reef, and also give myself plenty of time to explore the back roads of the Park’s Cathedral Valley unit.

I rolled into sleepy Escalante just past dawn, topped off the tank, bought the first cup of joe sold that day at the gas station, and turned north toward Hell’s Backbone.

Utah State Route 12 is possibly my favorite stretch of tarmac in the world - the road connects Escalante to Torrey, Utah via the small hamlet of Boulder Town. The ecosystems and scenery it transects have no rival. If you are ever presented with the chance, you must not miss it. I put it up against any highway anywhere in the world for its sheer beauty.

But, my goal was to stick to dirt roads - so I chose Pine Creek Rd/USFS 153 up and over Hell’s Backbone. Thousands of feet of elevation change would greet me over the tracks blazed by the Civilian Conservation Corps in the 1930s. USFS 153 was the old connector between Escalante and Boulder, an alternate America.

Hell’s Backbone tops out at 9000' in elevation. The road is well-maintained, so no particular off-road challenges were expected - but this route shows off what makes Utah so spectacular. The ever-varying and diverse landscapes that you can traverse in a single morning are mind-boggling.

The single-lane bridge that links the east and west halves of Hell’s Backbone is the engineering pièce de résistance on the route. First built as a timber span by the CCC, the canyon walls plunge 1500 feet from either side into the depths of the Box-Death Hollow Wilderness.

Even now, with the bridge long replaced by asphalt and steel, the 100 foot distance still feels sketchy.

It was Mother’s Day, so if I was going to be a good son, I would need some cell service eventually, and it’s not always easy to find in this part of the country.

But I was still committed to my dirt-exclusive route planning. After reaching the end of the Hell’s Backbone road, rather than tack north on Highway 12 over the Boulder Mountains to civilization, I took the Burr Trail east across the Waterpocket Fold, onto the Notom-Bullfrog Road, and kicked dust for Torrey, Utah.

In addition to a cell phone signal, Torrey also offered a fuel top-up and a handful of snacks. After calls to my mother, grandmother, and mother-in-law, I beat tracks for my brass ring - Cathedral Valley.

Famously, the southern entrance to Cathedral Valley fords the Fremont River just west of Caineville, Utah. The river never really gets too deep (except during flash floods), but the heavy run-off from a hard winter had carved a decent channel along the north bank.

Only one way to find out:

I fully admit to running the river four times. I’m not proud.

A few miles north of the ford brought me to the Bentonite Hills - a denuded and alien landscape that geologically links the slanted sandstone lands of the Waterpocket Fold with the towering buttresses of the Cathedral Valley.

Despite having visited Capitol Reef National Park many times before, I had never traveled to this most northern part of the Park. One of its great features is how Hartnett Road and Cathedral Road - the two main paths through the Valley - intersect a dozen or so BLM roads that lead you deeper and deeper into the wilderness. The opportunities for exploration reach in all directions.

Two roads that do manage to stay within in the National Park lead you to the Gypsum Sinkhole, the Glass Mountain, and the Temples of the Sun and the Moon. If you’re not curious about those landmarks just from their names alone, you’re probably reading the wrong blog.

Around one bend I noticed a distinct slot in one of the cliff faces and stopped to investigate.

The Gypsum Sinkhole did not disappoint. It looked like something straight out of Star Wars.

Further exploration led me to the Glass Mountain and the The Temples of the Sun and Moon.

Cathedral Valley Road itself is not particularly challenging - I saw two Subaru Outbacks and one Nissan Maxima navigating it with ease (you don’t have to do the river ford to access the Valley), so it was now time to tread on lesser traveled paths.

Let’s let the pictures do the talking:

I had already staked out my claim to a campsite in the National Park’s Cathedral Valley Campground earlier in the day, and after a solid afternoon of adventure, I returned well before sunset to enjoy the silence and the solitude. I had the entire campground, it seemed like all of Utah, to myself.

I look forward to returning to Cathedral Valley to dig further into its secrets - one day was not nearly enough given all the alternate tracks spinning off its main road. I think it may be one of my favorite corners of Utah now, and that’s saying something.

I had a bit of a celebration on my last night alone in the wilderness - a decent steak grilled medium rare over the fire with cracked black pepper and butter, paired with a Lumberyard (Flagstaff, AZ) IPA. I even ate a couple of veggies.

The night was - I admit it - lonely. And strangely quiet.

There were no birds at this campsite, no jays or crows or nuthatches to share my stories with. Just me and the Utah desert unfolding below. The scrub pines, the juniper and the sage all stilled themselves after the last of the evening breeze, and I climbed into the tent.

In Scipio, Utah (population 290) I stopped for gas. The credit card readers on the pumps were out of order, so I walked into the fluorescent convenience store to pay in advance for my fuel, to pay in advance for my return home.

The clerk behind the desk was a woman whose age I could not easily guess. She might have been 25, she might have been 40. She had rings on each finger, and she muttered curses at the register. I read “Sherry” on her name tag.

My mind was back in Cathedral Valley, replaying in frame-stop motion the herd of Mule Deer that bolted across the road in front of me as I drove up and out from the valley, into the snow-bound mountain passes once again, draining inexorably down to the interstates, and to the world.

“Where are you coming from?”, she asked.

“I was just in Capitol Reef. I took an alternate route.”

Rings flashing, snagging my credit card, “By yourself?”

“Yeah. I’m all alone on this trip.”

“Boy, I love it down there,” she said. “If I could get a weekend just for me, by myself, I don’t even know what I’d do with it.”

“Why don’t you?”, I asked.

Looking into the middle distance, Sherry sighed, “Oh, we’ve got four kids, my husband wouldn’t know what to do with any of them if I left for more than a day. Still, I know that country, and I know how to drive a Jeep. Maybe I will go.”

The register drawer jumped open, and my receipt chattered in the printer.

Maybe I will go.

As a bonus for hanging in there on this image-heavy post, here’s the uncut version of my Fremont River ford. I love how the wind dislodges my phone, and then manages to bring everything back into frame just before I arrive on the scene.