In 1955 the USAF issued General Operational Requirement No. 38, calling for a new bomber merging the speed of the B-58 with the payload and range of the B-52. A nuclear-powered aircraft was considered under Weapons System 125A, while a more conventional jet was organized under Weapons System 110A. A related program, WS-110L, was established to develop a high-speed reconnaissance aircraft, but this was suspended in 1958 when the USAF took an interest in the CIA’s OXCART program. Boeing and North American Aviation both submitted proposals in 1956, with aircraft powered by JP-4 and HEF/Zip Fuel and featuring “Floating Panels”, large fuel tanks integrated into the outer wings, which would be jettisoned for supersonic flight.

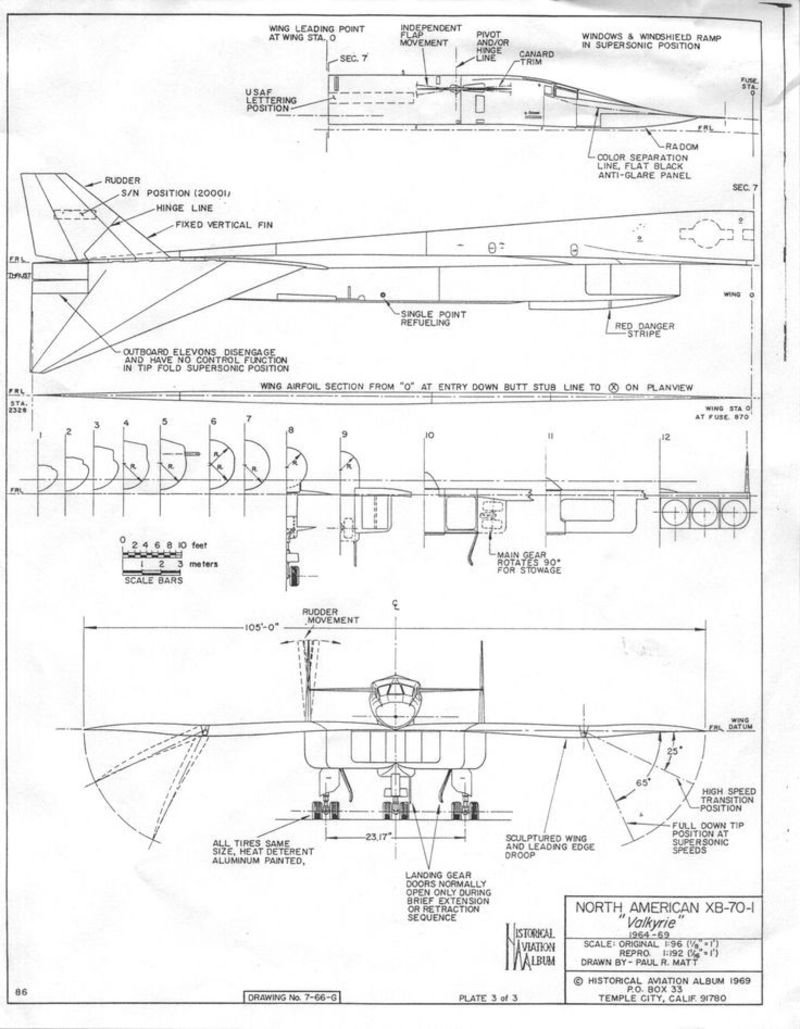

The USAF rejected both designs, deeming them too large and complex for operational deployment. Famed General Curtis LeMay was particularly dismissive, stating “This is not an airplane, it’s a three-ship formation.”. Both companies went back to the drawing boards, aided by the rapid progress of technology and copious amounts of data coming out of the various X-Plane programs. North American’s researchers came across a report titled “Aircraft Configurations Developing High Lift-Drag Ratios at High Supersonic Speeds”, and using ideas put forth in the document refined their concept to take advantage of Compression Lift. By carefully positioning the wing in relation to the bow shock created by high-speed travel, in conjunction with moving the engines into one large duct and adding movable wingtips, the shock wave could be captured and used to generate additional lift. This configuration had the additional effect of countering the rearward shift of the center of pressure at high speeds, which leads to a gradual nose-up attitude requiring downward trim of the maneuvering surfaces which causes drag.

Another issue would be friction-generated heating of the skin. North American solved the problem on their X-15 research plane by building the craft out of Inconel X-750, while Lockheed’s SkunkWorks went with a titanium alloy. For the WS-110A though, both approaches would be too expensive. The bomber would instead be constructed of laminated panels of stainless steel around a honeycomb foil core, with titanium being used in the engines, nose, and leading edges of the tails. Fuel would also be pumped around the airframe for cooling prior to burning in the engines. In order to fit the main landing gear around the engines, bomb bays and fuel tank, the bogies and oleos were designed to fold, rotate, and fold again. This action would be completed in 30 seconds.

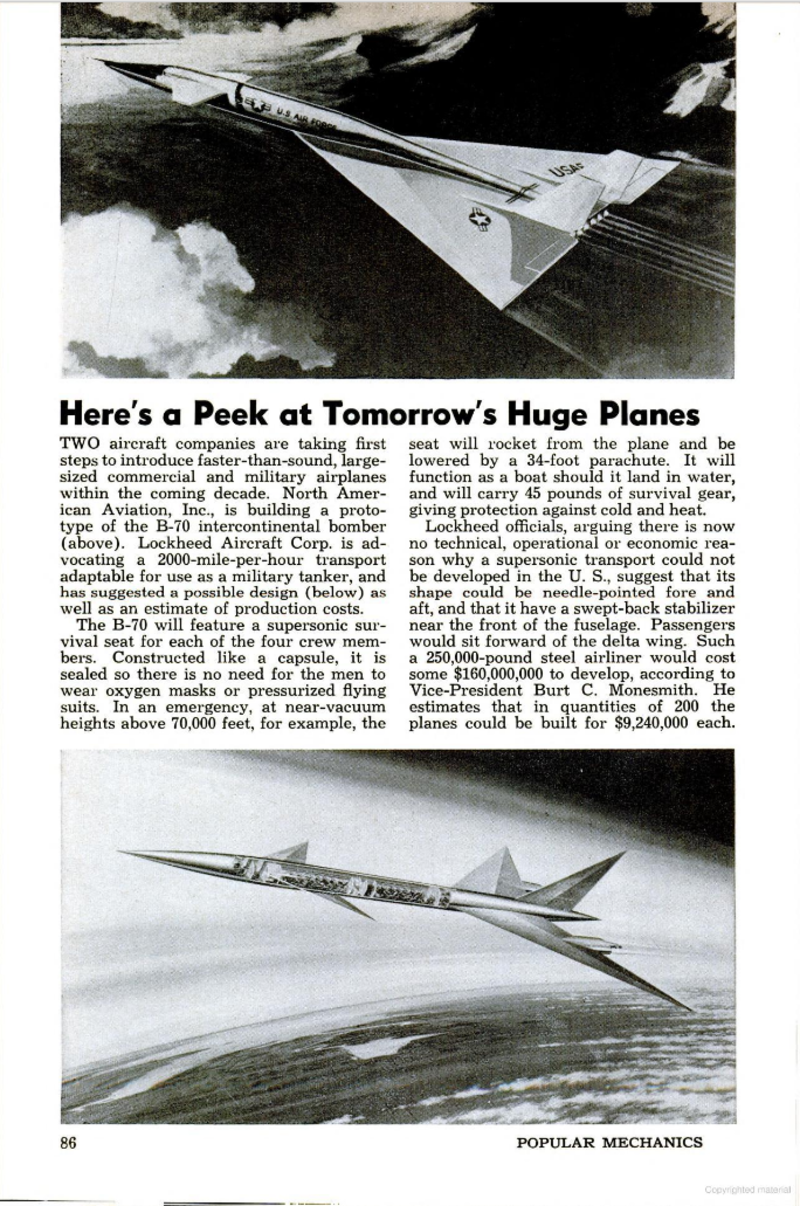

By September of 1957, the Air Force had issued final requirement of the design, calling for a cruising speed of Mach 3.0-3.2, a range of up to 10,500 miles, altitude over targets of 70,000-75,000 feet, and a gross weight of just less than 500,000 pounds. Further, the bomber would need to use the same hangars, runways and handling procedures as the B-52. By the end of the year, NAA was declared the winner over Boeing, and early the next year the plane was designated the (X)B-70, with the nickname “Valkyrie” being chosen from 20,000 entries submitted by USAF personnel. In order to cut costs, development of the engines, escape capsules and other systems were shared with North American’s (X)F-108 Rapier interceptor. In March of 1959, a mockup of the B-70 was reviewed by the USAF, after which provisions for air-to-surface missiles and external fuel tanks were requested. In April of 1960, a simplified drawing of the plane was shown to the world in Popular Mechanics.

Problems soon arose however, with the rapid development of surface-to-air missiles threatening any attack on the USSR, as well as ICBMs becoming the favored delivery system of nuclear weapons by both camps. President Eisenhower in particular was dismissive of the B-70, likening it to “ talking about bows and arrows at a time of gunpowder when we spoke of bombers in the missile age.” Further issues arose when the Zip Fuel and F-108 programs were both terminated, hampering technologies needed by the Valkyrie as well. In December of 1959, development was restricted to a single prototype. In the run-up to the 1960 presidential election, Eisenhower was painted as soft on defense by JFK, who had publicly endorsed the B-52, B-58 and B-70. Congress stepped in and appropriated first $155 million ($1.3 billion today), then a further $265 million ($2.3 B today). After taking office in 1961, and upon learning that the “Missile Gap” wasn’t, Kennedy canceled the XB-70 as unnecessary and economically unjustifiable”, and ordered it “be carried forward essentially to explore the problem of flying at three times the speed of sound with an airframe potentially useful as a bomber.” Curtis LeMay, now Air Force Chief of Staff, stepped back in, arguing for the B-70 in front of both House and Senate subcommittees. SecDef McNamara chastised LeMay, but the House Armed Services Committee stepped up with an appropriations bill directing the Executive branch to use $500 million ($4.2 today) to keep the Valkyrie, now redesignated the RS (Reconnaissance/Strike)-70. An agreement in March of 1962 between Kennedy and Carl Vinson removed the language, however, and the Valkyrie remained consigned to a limited test program.

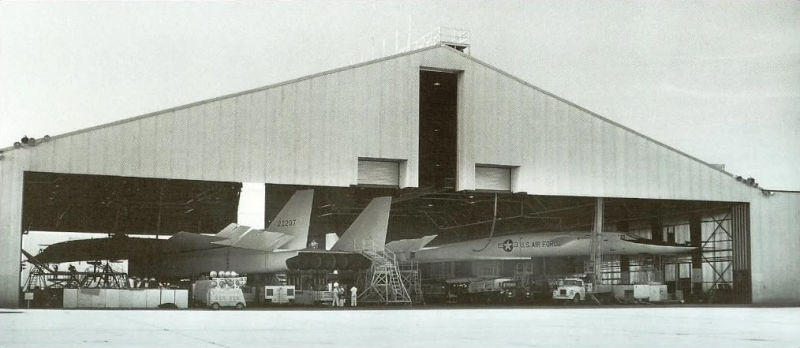

In May of 1964 the first XB-70 (AV-1, 62-0001) was completed, with AV-2 (62-0207) following in October. A third prototype was under construction, but was incomplete when funding was cut. The first flight was on 21 September 1964, from Palmdale to Edwards AFB, and was anything but trouble free. One engine was shut down after takeoff, and an issue with the XB-70's complex main landing gear prevented full retraction, limiting speed to just under 400mph. Upon landing at Edwards, the rear tires on the left bogie locked, causing the tires to rupture and a fire in the brakes. AV-1 broke the sound barrier on 12 October, and maintained speeds above Mach 1 for 40 minutes on the next flight on 24 October, which also saw the massive wingtips, each the size of a B-58's wing, to be partially lowered. These early flights revealed issues with the honeycomb panels, resulting in several leaving the airplane on two occasions and a limit of Mach 2.5 being placed on AV-1 for a time. Another issue that cropped up was that the anti-flash paint was less flexible than the airframe, which caused the paint to peel off.

These issues were solved with AV-2, which also featured a five degree dihedral in its wings to improve stability. AV-2 attained the highest speed of the two planes, Mach 3.08 for 20 minutes, and held Mach speeds for the longest, 3.06 for 32 minutes. After completing initial flight testing, the XB-70s began a joint USAF/NASA test program to measure the properties of sonic booms and their effects on the ground in preparation of the American SST program. It was at this time that AV-2 was destroyed in a mid-air collision.

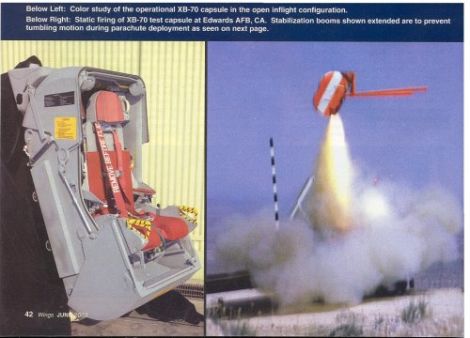

XB-70 AV-2 was to be the centerpiece of a formation flight also featuring an F-4, F-5. F-104 and a T-38, which General Electric (manufacturer of the engines for all five aircraft) organized for a photoshoot. Test pilot Joe Walker, in the F-104, was holding position off the right wing of the Valkyrie when the Starfighter drifted into the wingtip of the B-70 and was flung across both tail fins and the left wingtip before bursting into flames and breaking up. AV-2, crippled by the damage, entered a flat spin. Co-pilot Al White triggered the ejection capsules for himself and pilot Carl Cross, but found his elbow was caught between the halves of the clamshell.

The inability of the capsule to close completely prevented the hotmike from triggering, and Al found himself unable to talk with Carl or the ground. As the Valkyrie plummeted closer to the ground, White managed to free his arm and eject, though for reasons unknown Carl did not eject and died when the plane impacted the desert floor. A USAF investigation of the incident determined that Joe Walker in the F-104 could not see the XB-70's wing, and was thus unable to visualize his position relative to the plane. As a result, he had drifted too close and was drawn into the wingtip vortex, which pushed the smaller plane into the Valkyrie.

After the accident, AV-1 was fitted with sensors to complete the XB-70's part in the National Sonic Boom Program. After that sequence was concluded, the XB-70 also investigated a tendency of high-speed aircraft to see unwanted changes of altitude. Small vanes were fitted to the nose to measure the response of the B-70's stability augmentation system.

North American tried several times to save the project, pushing, with varying degrees of commitment, turning the bomber into a reconnaissance platform, a launch platform for the proposed X-15 Delta, or as an SST (possibly even as Air Force One). The SST program went the furthest, with Congressional representatives being invited to view one of the aircraft with mock windows painted on the fuselage.

None of these possibilities came to fruition, though, and on 4 February 1969 AV-1 was flown to Wright-Patterson and ensconced in the the USAF Museum.