In 1977, the Aircraft and Shipbuilding Industries Act was passed in the UK, which called for the merger and nationalization of the remaining British aircraft manufacturers: British Aircraft Corporation, Hawker Siddeley Aviation, Hawker Siddeley Dynamics and Scottish Aviation. The resulting firm was called British Aerospace (BAe), which in addition to continuing to service legacy systems like the Tornado, Concorde, Nimrod, Jaguar and Hawk, developed its own aircraft like the Harrier family and the Eurofighter Typhoon.

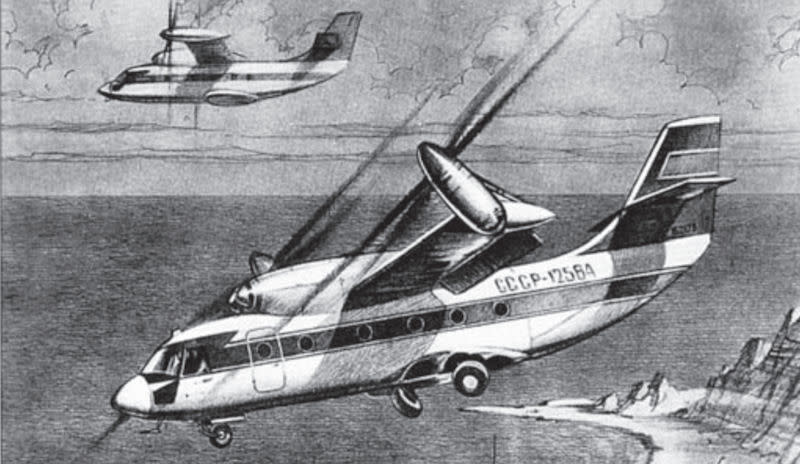

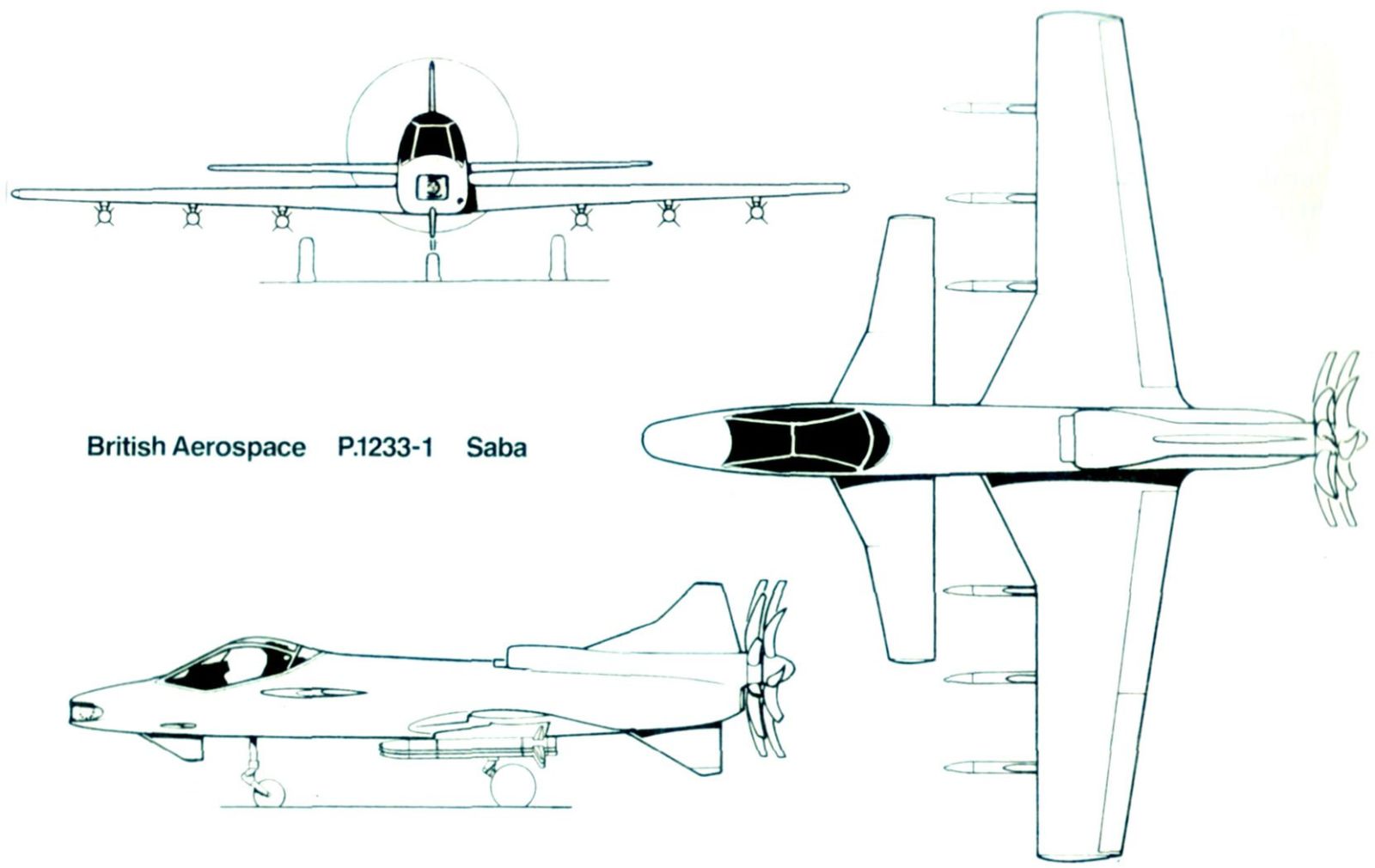

One of the projects BAe was also working on was Saba (Small Agile Battlefield Aircraft), which was intended to hunt down Soviet helicopters like the Mi-24 “Hind”, as well as emerging threats like the Mi-28 “Havoc” and Mi-30/32 Vintoplan tiltrotor.

BAe’s Future Projects team, known as ‘Kingston’, began designing a new aircraft that could out maneuver helicopters as well as provide close-air support. The new plane would be able to operated day or night, from rough short fields, with a long loiter time as well as sufficient speed to reach targets quickly. The model P.1233-1 incorporated a canard, unswept wings, dorsal and ventral tail surfaces and propfan propulsion.

Development of propfans, also known as unducted fans or open rotor engines, began in the 1940s as research into turbojet engines and sweeping wing surfaces accumulated. Engineers reasoned that a jet engine coupled to a propeller made up of a number of highly-swept blades could match the performance of a turbojet, but maintain the fuel efficiency of piston engines. Early attempts ran into issues with materials, shaping and noise, so the idea was temporarily abandoned. Improvements in materials, especially resin-impregnated composites and the shaping thereof, as well as expanded research into aerodynamics, reignited research into propfans in the 1960s and 1970s, with Hamilton Standard and General Electric both working on designs.

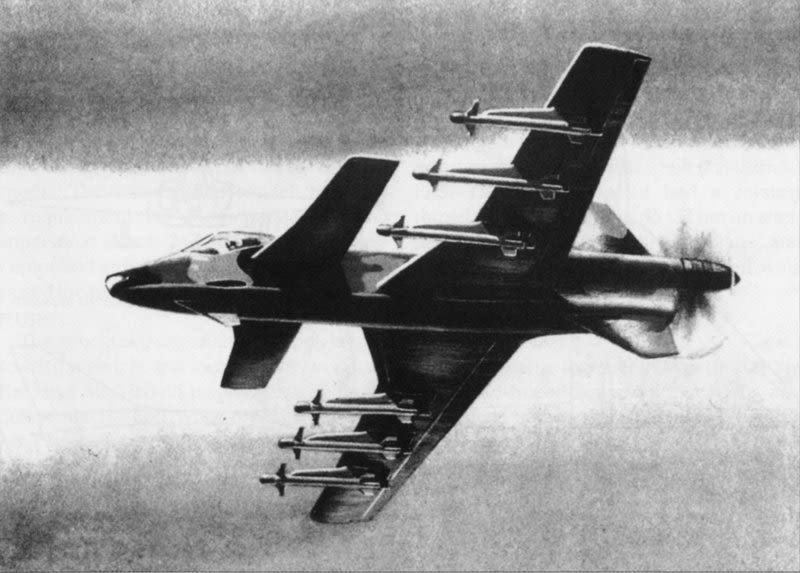

As its name implied, the P.1233 was small, with a wingspan of just 11m (36'), and light, maximum TO weight of under six tonnes (13,200lbs). This compactness allowed the P.1233 to turn 180° in 5 seconds and in a radius of just 150m (490'). The unique propfan engine, as well as the dorsal intake, would have reduced the SABA’s IR fingerprint, and its low ceiling would have granted some measure of protection against radar-guided missiles. The P.1233's own armament consisted of six AIM-132 ASRAAM air-to-air missiles as well as a 25mm canon.

Nose mounted sensors included an IR seeker and a laser designator, opening up the aircraft to carrying anti-tank weapons such as the AGM-65 Maverick, AGM-114 Hellfire, or the Brimstone missile.

BAe also pitched the SABA to the US Army and USAF as a COIN/CAS aircraft, potentially supplementing or replacing the A-10 Thunderbolt II, but after initial interest both cooled on the idea. The RAF was similarly interested in the concept, but the collapse of the USSR and the end of the Cold War ended the program before a prototype could be built.