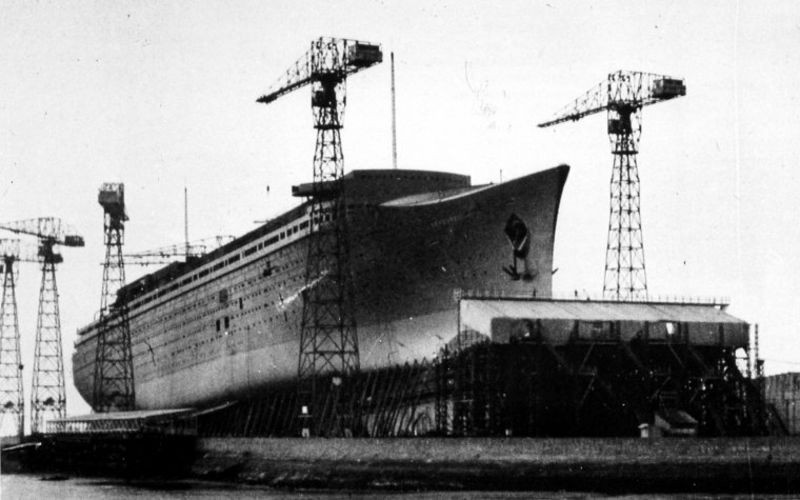

Launching of the Normandie – October 29, 1932

A day late, but whatever.

There are a few absolute statements one can make that are so uncontroversial, so inarguable, that there is virtually zero fear of any backlash. Like saying “Donald Trump is a jackass” at a Hollywood cocktail party – everyone in the room is guaranteed to agree with you, so feel free to yell it. Among maritime historians and ocean liner enthusiasts, one such statement is “The Normandie was the greatest ocean liner ever” - while such absolutes are sometimes hard to quantify, there is very little argument there, the SS Normandie certainly has a stronger claim to that than probably any other ship ever built.

Unlike the British and German firms, Compagnie Generale Transatlantique SA (CGT) – typically branded in French speaking markets as “TransAt” and in English speaking makets as “The French Line” - did not build classes of two or three or more largely identical ships, instead, they preferred to build their flagships one at a time, using operational experience to make each succeeding ship better and more refined, rather than committing to one design early on. The French Line’s series of great Atlantic liners started with the 4-funneled SS France of 1912, with her Versailles-inspired interiors, continuing with the Art Nouveau Paris of 1921, and finally, the sleek early Art Deco Ile de France of 1927. Capping it all was the supremely technologically advanced and elegant Normandie of 1935.

Despite, or perhaps in part because of, the Great Depression, the 1930s was a period of increasingly intense competition on the transatlantic trade, the United Kingdom, Italy, Germany, and the Netherlands all commissioned new generations of large, fast, modern liners, and even the United States would do likewise in 1940. France couldn’t be left behind, and CGT placed an order with Chantiers de Penhoët in Saint Nazaire (which they also controlled) in 1930, with construction commencing in January, 1931.

The new ship would have a radically modern hull shape, thanks to naval architect Vladimir Yourkevich. Yourkevich had previously worked for the Russian Imperial Navy, but had fled to France after the Bolshevik revolution and had spent the previous decade trying to interest Western navies, shipbuilders, and shipping companies in his ideas. Normandie’s hull flared out slightly at the sides under the waterline to improve stability, and featured a bulbous bow to reduce drag through the water. Extensive testing of scale models in water tanks confirmed the performance advantages of Yourkevich’s proposals, and since competing companies in Britain had deemed his designs too radical, CGT would have a unique advantage. Yourkevich was hired by CGT as their full-time in-house architect, and given virtual free reign on Normandie’s hull.

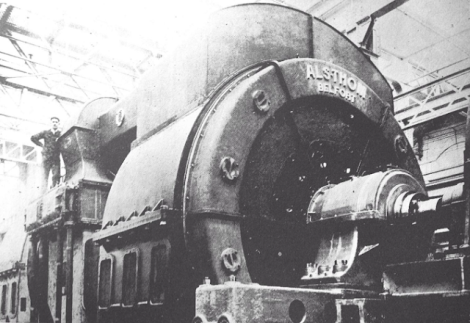

The powerplant would be equally innovative. A steam turbo-electric hybrid system, in which the propellers themselves would be directly driven by Alstom electric motors, fed by turbo generators, which, were, of course, powered by the ship’s steam turbines. In practice, this ran almost totally silent, and eliminated almost all noticeable vibration from the drivetrain. The ship achieved 32.15 knots on sea trials, and was able to execute an emergency stop from top speed in a little over a mile. At 200,000 peak horsepower (160,000 sustained), it remains the most powerful steam turbo-electric plant ever constructed.

Innovation continued topside, with Normandie becoming one of the first ships equipped with radar. The exhaust uptakes, which traditionally ran straight up from the boiler rooms to the funnels, were split in half and moved to the sides, allowing a procession of wide, open, public rooms without obstructions. Passenger cabins were equipped with radio telephones, allowing phone calls to be placed to any number in Europe or North America while underway. The bow featured a distinctive breakwater, designed to keep waves that crashed over the top in winter storms from slamming into the forward superstructure – a feature directly copied on the later France of 1962 and Queen Mary 2 of 2004.

Due to American immigration restrictions killing off the steerage trade after WWI, the majority of Normandie’s passenger space was devoted to First Class.

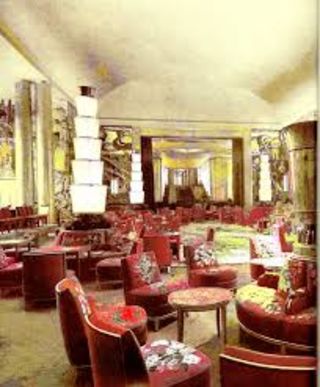

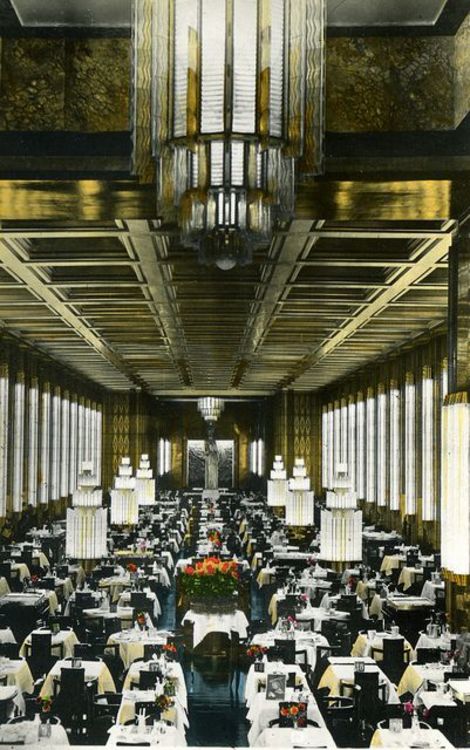

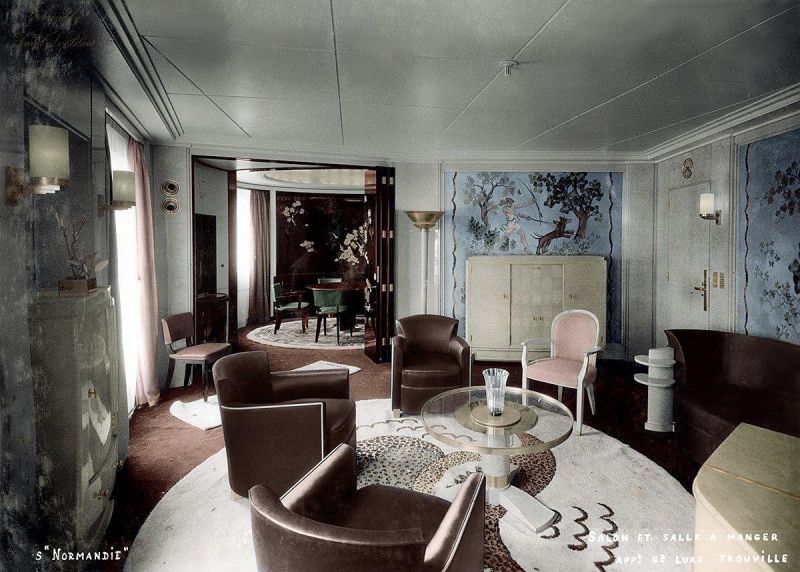

The interiors were, naturally, decorated by the finest artisans France had to offer. Chairs were upholstered in custom woven Aubusson tapestries, the First Class Dining Room was the largest room afloat in the world – 28 ft tall, 46 ft wide, and, at 305ft, longer than the Hall of Mirrors at the Palace of Versailles. It was lit with 12 Lalique glass pillar light fixtures, which reflected off 38 nearly floor-ceiling Lalique glass light columns installed on the gold leaf covered walls to bathe the windowless room in light. Passengers entered through massive 20ft tall bronze doors and processed down a sweeping grand staircase, and the cuisine was reported in contemporary reviews to be easily the finest of any shipping line in the world. The Winter Garden featured tropical plants and cages filled with live song birds, and the top of the line suites featured 3 bedrooms, a private balcony, a dining room, and a large living room complete with grand piano. The ship’s captain was provided with an equally large and well finished stateroom, and even Tourist Class (which replaced Third Class after the immigrant trade dried up) was still fairly luxurious – with their own spacious public rooms trimmed in exotic wood paneling.

Care was taken to create an uncluttered appearance on the ship’s upper decks, for style and practicality. All cargo handling equipment was carefully recessed into enclosures, and the dummy third funnel hid all the air handling equipment for the central air conditioning system. This created vast expanses of unencumbered open deck space, that allowed for the first regulation-size tennis court at sea. In an era when even one was a luxury, Normandie featured two separate swimming pools – one for First Class, one for Second, with the First Class pool featuring an artificial sand beach.

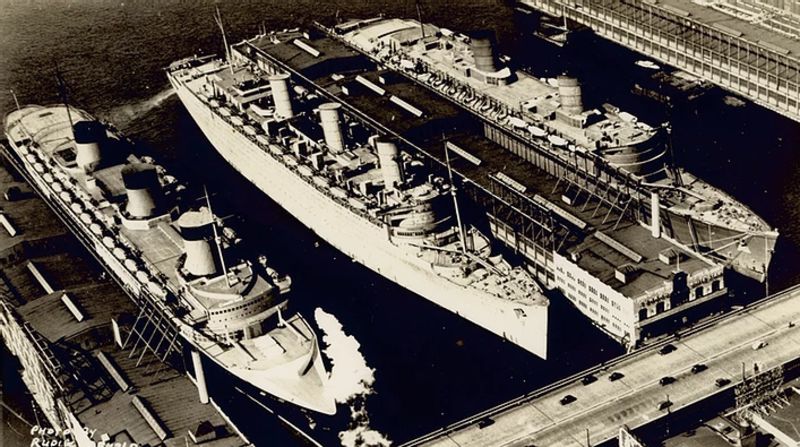

After over 2 years of work, Normandie was finally launched on October 29, 1932 in front of thousands of spectators. Three more years would be required to complete fitting out. The maiden voyage on May 29, 1935 attracted a crowd of 50,000 to see her off. At 79,280 gross tons and 1,029 ft. long, Normandie was easily the largest ship ever built at the time – over 20,000 tons larger than the Cunard White Star Line’s Majestic. She also proved to be the fastest, shattering the transatlantic speed record on her maiden voyage, averaging over 30 knots in each direction, and reaching New York in 4 days, 3 hours, 2 minutes. 100,000 spectators gathered in New York to watch her arrival, flying a 30 ft blue pennant to celebrate her achievement.

The size and speed records wouldn’t last for long, though, as Cunard White Star’s new Queen Mary entered service in 1936 at 81,000 gross tons and a slight edge on speed. Not to be outdone, during the winter of 1936, CGT had Normandie refitted with an enlarged superstructure, creating additional lounge spaces for Tourist Class, raising her gross tonnage to 83,423, making her again the largest in the world. Normandie and Queen Mary traded the speed record back and forth a few times, until the British ship took it for good in 1938. Although the Queen Mary had a comparatively old-fashioned hull and superstructure against the sleek, hydrodynamically and aerodynamically optimized Normandie, the British ship was more powerful, and brute force is what ultimately won out.

Queen Mary also proved more successful economically, too. Cunard White Star had decided not to give their new liner a First Class, instead making Cabin Class (the equivalent of 2nd) the top grade (giving 1st class accommodations at 2nd class prices), with Tourist Class bumped up to 2nd, and a new, cheaper Third Class created underneath. Queen Mary had also been designed as a commercial venture from the start, while Normandie, with her expensive construction and high manning requirements, was intended from the start to require large government subsidies to operate. In addition, it was sometimes claimed that Normandie’s interiors may have been too grand, too imposing and alienating to American passengers, who were the lifeblood of the transatlantic business. The warmer, more informal English country house style of Queen Mary may simply have been more inviting.

Upon the outbreak of WWII, Normandie was inbound to New York. She sped into port, and, with France not needing a large troop ship at the time, was laid up for safekeeping under the care of a skeleton maintenance crew. Following the fall of France, the Vichy government demanded the ship’s return, at which point the United States took her into “protective custody” to prevent her from falling into the hands of the Axis. Once the United States entered the war officially in December, 1941, Normandie was seized outright and commissioned into the US Navy as the troop transport vessel USS Lafayette. While undergoing conversion work at Pier 88 in Manhattan, Lafayette caught fire on February 9, 1942, when sparks from a welding torch ignited a nearby pile of life jackets. Most of the ship’s systems had been deactivated during the conversion process, so firefighting had to occur from FDNY firetrucks parked on the pier and fireboats pulled alongside. The boats pumped more water on board than the trucks, creating a balance problem, which caused Lafayette to capsize the next day.

The true cause of the fire wasn’t officially disclosed for some time, and rumors circulated that it may have been sabotage by German agents, which is referenced in Alfred Hitchcock’s 1942 film Saboteur, in which the villain, a German spy, arrives in New York for a clandestine meeting and pauses before the hulk of Lafayette, giving a knowing glance toward the camera.

Although badly damaged, the urgent need for ships, and the fact that Lafayette was blocking two large slips lead the Navy to decide on salvage at a cost of $5 million, which required the entire superstructure to be demolished before the parbuckling process could begin. The ship was righted and towed away on August 7, 1943.

At the time, a suggestion was made that she be rebuilt as an aircraft carrier, but the thirsty high speed engines and unarmored hull made that impractical. Furthermore, drydock inspection revealed significant structural damage to the hull, which, along with the fire damage, water damage, and removal of the entire superstructure, made rebuilding uneconomical. The hulk of Lafayette was laid up in New York harbor for the duration of the war. When hostilities ended, the US Government offered to return the ship to the French Line, and her original designer, Vladimir Yourkevich, suggested that the hull could be cut down in size with the removal of several central sections to make rebuilding more cost effective, but the high cost of repairs and the need to replace almost their entire fleet lost in the war caused CGT to refuse. The former Normandie was sold to Lipsett Inc., a scrap metal yard in New Jersey and demolished in 1946.