From the Planes You’ve (Probably) Never Heard Of Department of Wingspan, we bring you the Curtiss XP/YP-37.

Before the outbreak of WWII, the US military had developed a penchant for radial engines. Not only were they powerful, they were also air-cooled, which meant there was no need for the complicated radiators required for liquid cooling and, as a result, radial engine technology in the US became highly advanced. But on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, European designers had a preference for sleek inline engines. While the inline engine can be a bit more complex, it has the benefit of being more aerodynamic, though the radiator remained an Achilles heel in combat.

In the early 1930s, Curtiss was working on the latest in their series of Hawk fighters, the P-36 Hawk and, like many other fighters of its day, the P-36 was powered by a Pratt & Whitney R-1830 Twin Wasp radial engine. By all accounts, it was a fine little fighter and displayed good maneuverability. But fighters in Europe were emerging with slender inline engines that outpaced the Hawk. and the Army thought that an inline engine might make it more competitive. So the Army invested in the development of their own inline engine, and gave the Allison Engine Company, a division of General Motors, $500,000 (more than $9 million today) to develop the 12-cylinder V-1710, so-named for its 1,710 cubic inch displacement. A single Consolidated P-30 testbed, known as the XA-11A, received the first of the new engines

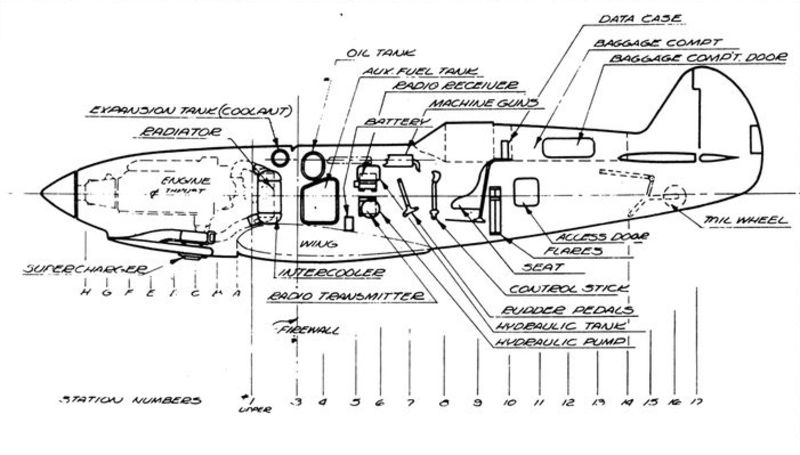

But the P-30 was designed from the start to hold an inline engine, and fitting the V-1710 into the P-36 posed a significant challenge for Curtiss. The Hawk had been designed around the comparatively compact Twin Wasp radial, so the aircraft had to be modified to fit the V-1710 and all its plumbing. In 1936, Curtiss took a single P-36, kept the wings and tail, but stretched the fuselage by four-and-a-half feet to make room for the engine, radiator and turbo-supercharger. With all the engine and associated bits up front, the cockpit had to be moved far to the rear to help balance the center of gravity. This new aircraft, dubbed the XP-37, looked more like a race plane than a fighter.

Despite the unreliable turbo-supercharger, the Army was generally pleased with the performance of the XP-37. They had wanted a fighter that could fly in excess of 300 mph, and the XP-37 managed a respectable 340 mph at 20,000 feet—when the turbo-supercharger was working properly. Pilots, however, were none too happy about the nonexistent visibility over almost comically long nose, which made it impossible to see the ground during takeoff and landing. Nevertheless, the Army placed an order for 13 pre-production aircraft which now became the YP-37.

With the YP-37, Curtiss tried to address some of the shortcomings of the XP-37. The airplane grew another 22 inches in length while also moving the cockpit forward, though only slightly. They also installed an updated V-1710 engine with an improved turbo-supercharger. But the YP-37 ended up 450 pounds heavier and actually lost nine mph of top speed. And the “improved” turbo-supercharger turned out to be just as frustratingly unreliable as the first.

Ultimately, the YP-37 did not turn into the V-12 speedster the Army was looking for, and the project went no further. Most of fighters ended up at the Army’s school for mechanics, and Curtiss turned its attention to the P-40 Warhawk of Flying Tigers fame, an Allison V-1710-powered fighter that had a significantly more successful career. And once a reliable turbo-surperchager was developed, the V-1710 found a home in the remarkable Lockheed P-38 Lightning, the Bell P-39 Airacobra, and the Bell P-63 Kingcobra.

Connecting Flights

For more stories about aviation, aviation history, and aviators, visit Wingspan. For more aircraft oddities, visit Planes You’ve (Probably) Newver Heard Of.