From the earliest days, earthbound humans have envied the birds and their effortless flight. Likely even before the work of 15th-centrury polymath Leonardo da Vinci, scientists and engineers searched for a way to slip the surly bonds of Earth and soar with the birds. Many tried—and many died. Humans first left the ground in 1783, when the Montgolfier Brothers took to the air in their hot air balloon. And while that flight, along with future balloon advancements, got aeronauts into the sky, they were still bound to the wind currents, and were unable to turn and soar or control their flight. Other inventors, like Otto Lillienthal, pioneered gliders that could carry a man from a height, but powered flight was still just a dream. It wasn’t until 400 years after Leonardo that two bicycle builders from Ohio would build and fly the world’s first heavier-than-air, powered, and controllable aircraft. Though they weren’t the first to build and fly an airplane, theirs was the first that could be fully controlled.

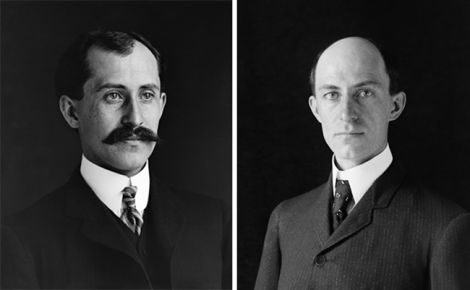

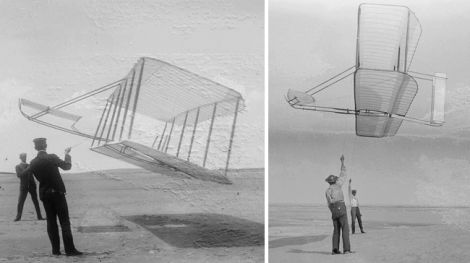

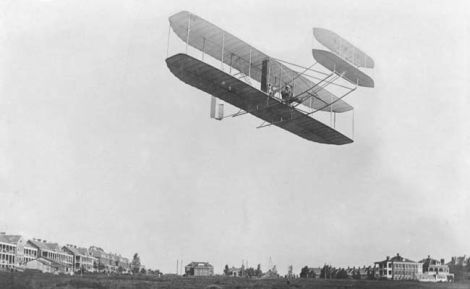

Following in the footsteps of Lillienthal, Wilbur and Orville Wright began with detailed studies involving gliders. They believed that the problems of aerodynamic wings and sufficiently powerful engines were surmountable or even already solved, and they focused on developing a system of control that would govern movement of the airplane in three axes of flight: roll, pitch and yaw. Piggybacking on the work of other designers, the Wrights built ever more complex kites and gliders. Beginning in 1900, they carried out their experiments at Kitty Hawk, on the coast of North Carolina, where they could take advantage of the ocean breezes and use the tall sand dunes as a launching point. The relatively remote location was also far away from prying eyes. The gliders used two wings, which the Brothers called “double decker,” and a single forward control surface for pitch.

Based on observations of birds, the brothers developed a system of warping the wingtips of their flyer to induce roll, a precursor to the modern aileron. At first, they didn’t feel that a rudder was necessary, that the wing warping would provide sufficient directional control. However, they soon found that this arrangement was not sufficient, and by 1902 they added a steerable rudder behind the pilot to control yaw. In over 700 test flights in September and October of 1902, the brothers developed their wing warping technique and performed longer and longer flights, with the longest lasting 26 seconds and covering 622 feet. A significant breakthrough came with their understanding of how the rudder acts to control the aircraft in a turn. Rather than initiating the turn as one might imagine it would on a boat, the rudder helps aim the aircraft while it is already turning, countering the adverse yaw caused by the lifting wing. With this problem solved, it was time to add an engine.

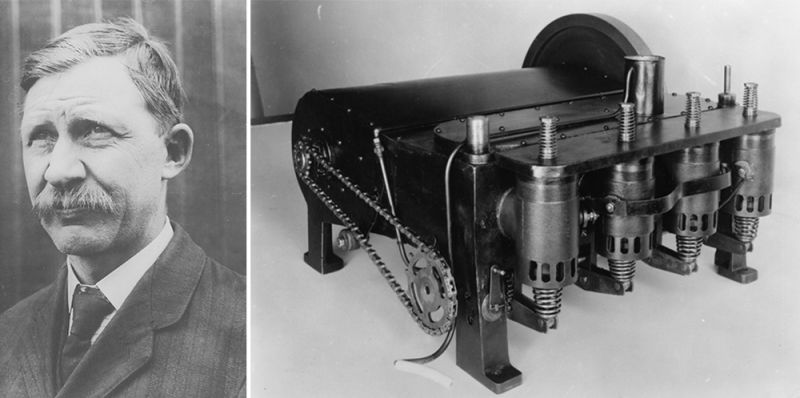

Since no suitably light powerplant could be found, the Wright Brothers decided to build their own. They called on Charlie Taylor, a mechanic in their Ohio bicycle shop. Based on drawings provided by the Wrights, Taylor constructed a simple, four-cylinder engine in just six weeks, with a block cast from aluminum to save weight, and with a rudimentary gravity-fed carburetor. The diminutive engine produced 12 horsepower and weighed 180 pounds, and turned the flyer’s two propellers through heavy-duty automobile chains. With a plane and and engine, what the brothers now needed was a propeller. Common sense dictated a design similar to a boat propeller. After all, air and water are both fluid mediums. But there was no data to support whether or not such a design would work. And here, the Wrights had another important inspiration: rather than build a propeller like one for a boat that pushes water backwards for propulsion, they constructed the propeller as a rotating wing, one that would push (or pull) the airplane through the air. Their first propellers were eight-feet in diameter, carved from wood, and would be mounted behind the pilot. Fully built, the entire Flyer weighed 605 pounds and cost less than $1,000 to build.

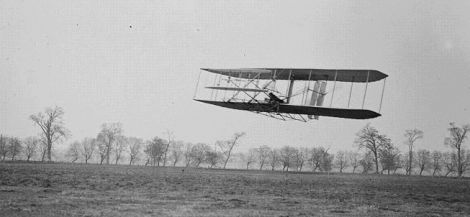

The brothers flipped a coin to see which would be the first to pilot the Flyer. Wilbur won. The first attempt at flight was made on December 14, but lasted only three seconds before the Flyer landed hard on the ground, causing minor damage. After repairs, and observing a day of rest on Sunday, they made another attempt on December 17, this time with Orville at the controls. At 10:35 am, Orville rode the flyer off of its catapult rails and into a frigid 27 mph headwind, with Wilbur running alonside. The Flyer covered a distance of 120 feet in 12 seconds. Two more flights that day covered ever increasing distances, the third approximately 200 feet. Modern aviation was born.

The first Flyer was destroyed soon after the first flight when it was flipped by a gust of wind, and the brothers returned to Ohio to continue their experiments at Huffman Prairie outside of Dayton. Their original aircraft was refined into the Wright Flyer II with a redesigned wing and a more powerful engine. With this aircraft, the brothers were able to complete full circle flights that demonstrated the success of their control system. In 1909, they provided the US Army with their first aircraft, the Wright Model A Military Flyer, which was designated “Signal Corps (S.C.) No. 1.” And the refinement and development of the airplane continues to this day at an astonishing pace. Consider this: In 1903, Orville Wright flew at 27 mph about 10 feet off the ground. A mere 44 years later, on October 14, 1947, Chuck Yeager broke the sound barrier, flying the Bell X-1 at Mach 1.07 (about 660 mph) at an altitude of 45,000 feet. Amazingly, Orville Wright was still alive (Wilbur had died of typhoid fever in 1912). The world had gone from the first hesitant leap into the air to beyond the speed of sound in the span of one man’s lifetime.

If you enjoy these Aviation History posts, please let me know in the comments. And if you missed any of the past articles, you can find them all at Planelopnik History. You can also find more stories about aviation, aviators and airplane oddities at Wingspan.