Welcome to This Date in Aviation History, getting of you caught up on milestones, important historical events and people in aviation from January 30 through February 1.

January 31, 1958 – The first flight of the North American T-2 Buckeye. If you joined the US Navy to become a Naval Aviator at any time from the late 1950s to 2004, you likely did your primary flight training on the North American T-28 Trojan. The radial-powered Trojan would have helped you master basic flying skills, but if you wanted to be a jet fighter pilot, your next ride was another North American aircraft, the T-2 Buckeye. After developing proficiency in the Buckeye, you would then transfer to fighter aircraft, if you survived the learning process.

While not as fast or as sexy as a jet fighter, the Buckeye was designed with the student pilot in mind. It featured straight wings borrowed from the North American FJ-1 Fury, the Navy’s first operational jet fighter. As opposed to swept wings, straight wings offer better low speed handling characteristics and stability while learning to land on a moving deck. The original Buckeye, the T-2A, was powered by only a single engine, but North American outfitted the T-2B and later variants with two engines, an arrangement that was more common for Naval aircraft where having a second engine acted as an insurance policy while operating over the open ocean. With the T-2C, the Buckeye received a pair of General Electric J85 turbojets that could push the trainer up to a respectable 522 mph. In order to help ease the transition from the propeller powered Trojan, North American made the cockpit of the Buckeye similar enough that it would be familiar to the new pilot, an important selling point for the Navy, with the student and teacher seated in tandem, as they were in the Trojan. And North American also made the Buckeye tough enough to endure the pounding of inexperienced pilots slamming down on the deck for the first time.

Though the original Buckeye was unarmed, it did come with strongpoints under the wings to carry bombs, rockets or gun pods for armament training. Forty Buckeyes were exported to Greece, where they served with the Hellenic Air Force. These aircraft, designated T-2E, were outfitted with six stations under the wings that could carry up to 3,500 pounds of ordnance, and also had extra armor on the fuel tanks to protect them from ground fire.

The 50-year run of the Buckeye came to an end in 2008 when the Navy retired the T-2 from its training duties and replaced it with the McDonnell Douglas T-45 Goshawk, though a handful remained in service for testing duties or to serve as a director aircraft for aerial drones. The final operational flight of the Buckeye took place on September 25, 2015.

February 1, 2003 – The loss of Space Shuttle Columbia. The Space Shuttle first went to space in 1981 and, over the course of 30 years of operation, Shuttles carried out 135 missions and spent almost 1,323 days in space. A total of 355 astronauts from 15 different countries traveled on board five different Shuttles throughout the program. Before the launch of Columbia on January 16, 2003, only one Shuttle, Challenger, had been lost, in an accident claimed the lives of seven astronauts, one of whom would have been the first teacher to fly in space. Though safety procedures were improved after the loss of Challenger, spaceflight remains an inherently dangerous undertaking, and the Shuttle program would suffer another devastating loss 17 years after Challenger when Columbia broke apart during re-entry.

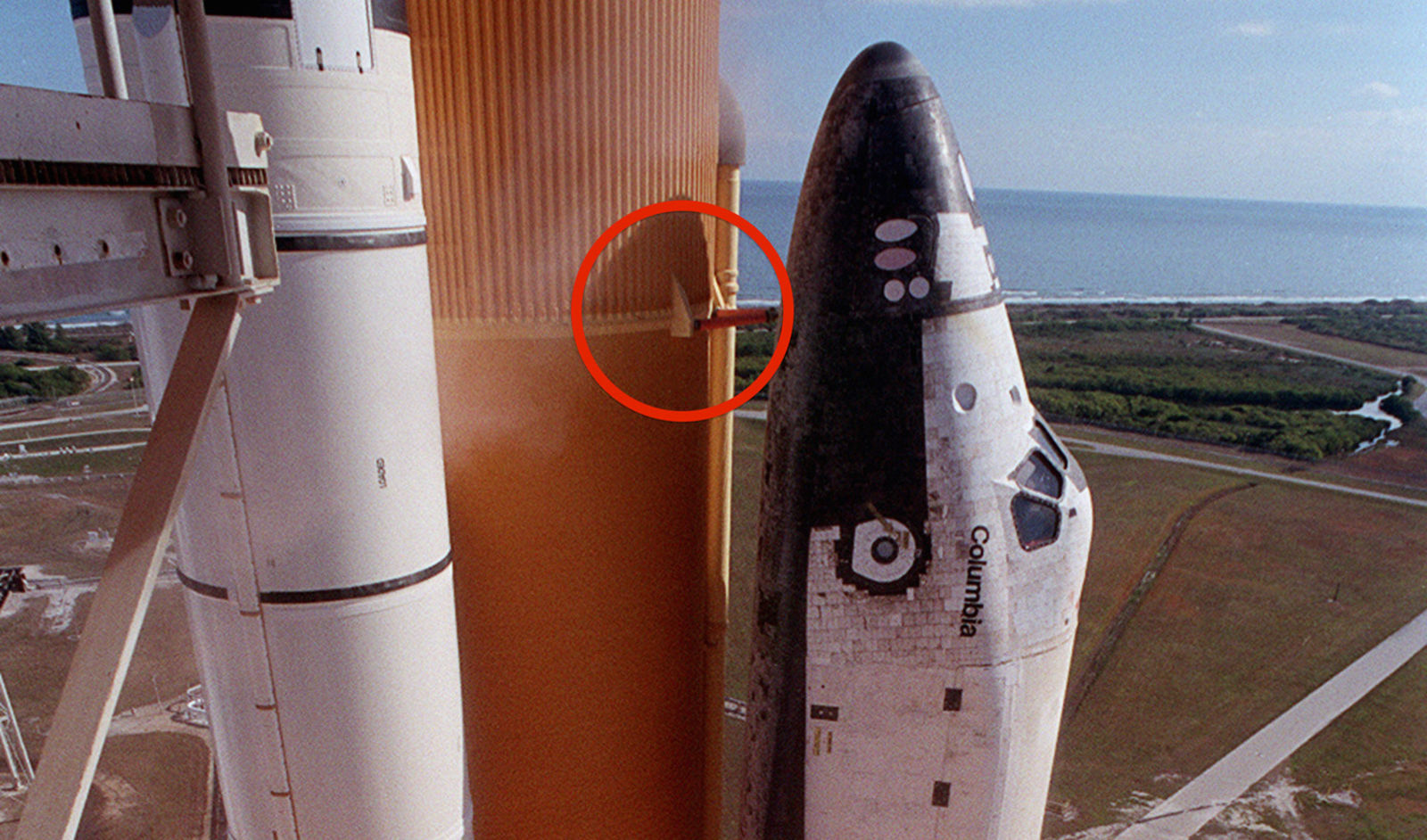

Space Shuttle Columbia launched on January 16, 2003 on STS-107, the 113th flight of the Space Shuttle program. Columbia carried a crew of seven: Shuttle Commander Rick Husband, Mission Specialist David Brown, Shuttle Commander Rick Husband, Mission Specialists Laurel Clark, Kalpana Chawla, and Michael Anderson, Pilot William McCool, and Israeli Payload Specialist Ilan Ramon. When Shuttles blasted off, it was not uncommon for pieces of the foam insulation covering the external fuel tank to break off. In some instances, the changes of insulation struck the orbiter but, in all previous launches, the foam didn’t cause significant damage to the vehicle. But when Columbia launched on that January morning, a large piece of insulation broke off the external tank and struck the the orbiter and made a hole in the leading edge of the wing. It was not until Columbia was in orbit that a routine review of launch footage revealed the foam strike, but it was impossible to ascertain the extent of the damage. Shuttle engineers on the ground requested that the Department of Defense provide imagery of the Shuttle in orbit that might have indicated the extent of the damage, but NASA managers blocked those requests.

It was also risky for the astronauts to assess the damage themselves. On this mission, Columbia did not carry the Canadarm remote manipulator arm, so assessing the wing would have required an unplanned spacewalk. And even then, the astronauts would have had to make a patch out of materials on hand, and there was no procedure for that, nor any assurance of success. Ultimately, NASA took the position that returning to Earth was the only option, and that warning the astronauts would do no good, since there was nothing that they could do to repair the damage.

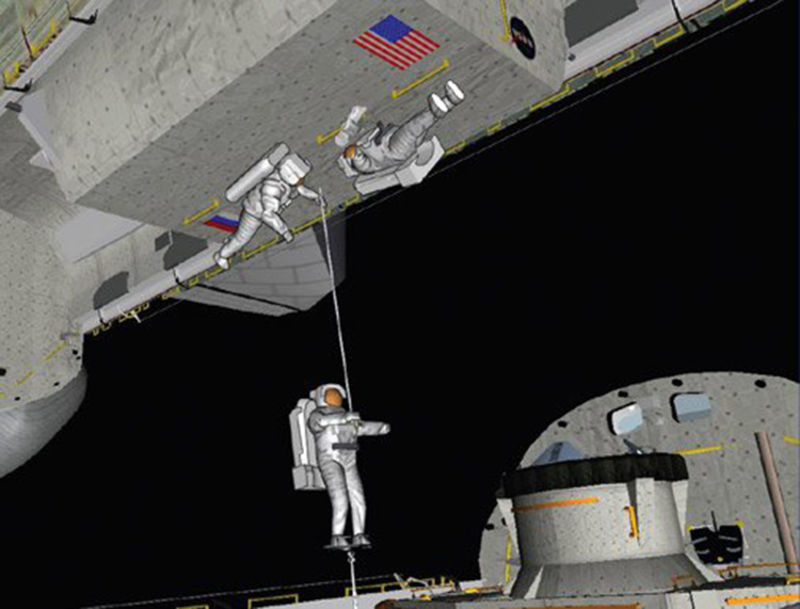

However, in the months following the disaster, investigators asked NASA engineers to report on other options that might have been carried out, either for repair of the Shuttle in space or for a rescue mission. The engineers reported that it might have been possible to use the Shuttle Atlantis, which was being prepared for a launch to the International Space Station in six week’s time for a rescue mission. But there were serious concerns about risking four more astronauts on a completely untried mission. Not only would Atlantis have to be prepped for launch in record time, the orbiter would have to rendezvous with Columbia, which had never been done before, and then the astronauts would have to perform spacewalks between the spacecraft to transfer from Columbia to Atlantis, as there was no way to physically dock the Shuttles. Two of Columbia’s astronauts had never performed a spacewalk. And all of this had to happen in less than 30 days, before Columbia’s food and water and, more importantly, its supply of lithium hydroxide, which was used to scrub carbon monoxide from the air, ran out.

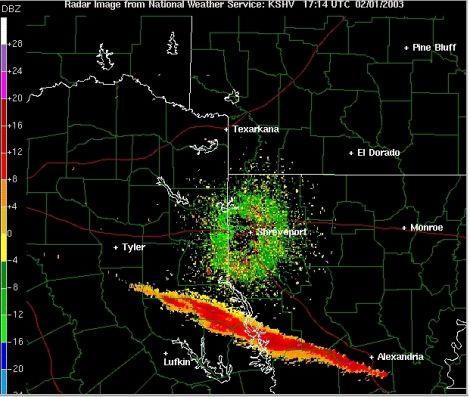

After completing its 15-day mission, Columbia and the crew began re-entry to the Earth’s atmosphere. The leading edges of the wings heated up to more than 2,800º F as the orbiter reached a speed of Mach 24.1 and, as feared, superhot atmospheric gases entered the damaged wing the orbiter began to break up. As re-entry continued over Texas and Louisiana, Columbia finally disintegrated, and pieces of the Shuttle were found over a huge swath of east Texas and west Louisiana. Recovery teams also discovered parts of the astronaut’s bodies. But, even as the Shuttle was coming apart, the investigation found that pilot William McCool, a US Naval Aviator and test pilot, was starting up the Auxiliary Power Unit in an attempt to manually fly the Shuttle to a safe landing.

Following the loss of Columbia, Shuttle missions were put on hold for two years, and construction of the International Space Station was halted. The foam insulation on the external fuel tank was redesigned, and many of the large pieces that had been prone to breaking off in the past were removed. NASA instituted inspections of the Shuttle once it reached orbit, and a designated rescue mission was made ready in the event that severe damage was found. The final 22 Shuttle missions were flown only to the ISS so the crew could wait there for rescue if damage during launch rendered the orbiter unsafe for re-entry. Only one mission was undertaken that didn’t go to the ISS, and that was flown to make repairs on the Hubble Space Telescope.

Short Takeoff

January 30, 2001 – The death of Johnnie Johnson, CB, CBE, DSO & two bars, DFC. Johnson was a fighter pilot with the Royal Air Force during WWII, and began his service in 1941 flying the Supermarine Spitfire. Over the course of 700 operational sorties Johnson scored 34 individual victories and three probable shared victories. He was also credited with damaging a further 10 Luftwaffe aircraft, as well as destroying one on the ground. His tally of victories made him the highest scoring Allied fighter ace versus the German Luftwaffe of WWII. He continued flying in Korea in the Lockheed F-80 Shooting Star, though he scored no further victories. For his service in Korea, Johnson was awarded the Air Medal and Legion of Merit from the United States.

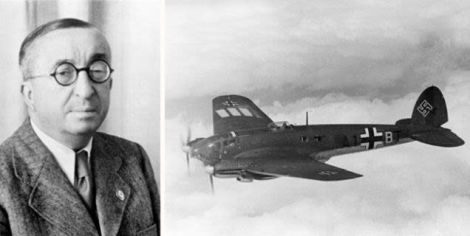

January 30, 1958 – The death of Dr. Ernst Heinkel. Born on January 14, 1888, Heinkel was a German aircraft designer and manufacturer who supplied some of the most iconic German aircraft to serve in the Spanish Civil War and WWII. He established the Heinkel Flugzeugwerke in 1922 and, after Adolf Hitler came to power in 1934, Heinkel provided many of the aircraft that Hitler used to build up the strength of the Luftwaffe, notably the He 111 medium bomber, which made its debut in the Spanish Civil War and served as the backbone of the German bomber fleet throughout WWII. Heinkel also produced the world’s first turbojet-powered aircraft in the He 178, and the world’s first rocket-powered plane in the He 176. Heinkel died in 1958.

January 30, 1948 – The death of Orville Wright. Along with his brother Wilbur, Orville Wright is credited with helping to design and construct the world’s first successful powered and controlled airplane and the first to achieve sustained heavier-than-air flight. After the toss of a coin, it was Orville who piloted the famous first flight on December 17, 1903. Following Wilbur’s death from typhoid fever in 1912, Orville took over the work of securing patents for their creation, further developing their flying machine, and marketing it to the US military, and finally sold the company in 1915. Orville continued his work in aviation by serving on the board of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA, the predecessor to NASA) for 28 years. On April 19, 1944, Orville took his last ride in an airplane, a Lockheed Constellation piloted by Howard Hughes. During the flight, Wright commented that the wingspan of the Connie was longer than his first flight. Orville’s death came soon after Chuck Yeager broke the sound barrier in the Bell X-1. The world had gone from first flight to supersonic flight in one man’s lifetime.

January 30, 1933 – The first flight of the Curtiss T-32 Condor II, a biplane airliner and bomber that was also used by the US Army as an executive transport. Production aircraft were outfitted as 12-passenger luxury night sleeper transports and served with Eastern Air Transport and American Airways. The US Army Air Corps purchased two Condors which received the designation YC-30, and one was fitted with extra fuel tanks and took part in the United States Antarctic Service Expedition, Admiral Richard Byrd’s third exploration of the Antarctic. Curtiss also produced eight armed bomber versions which were exported, and a cargo version for Argentina. Curtiss produced a total of 45 Condor IIs.

January 31, 2011 – The death of Charles Huron Kaman, an American inventor who developed a line of helicopters that are known for their use of dual, intermeshing rotors that counter-rotate, thus eliminating the need for a tail rotor. After working for Igor Sikorsky, Kaman developed his first helicopter, the K-125, and the improved K-225 became the first helicopter powered by a gas turbine engine. Kaman went on to develop more helicopters for the US military, such as the HH-43 Huskie, which flew more rescue missions in Korea than any other helicopter. The SH-2 Seasprite, a traditional helicopter design, saw extensive use with the US Navy, and the K-MAX, a medium lift utility helicopter that has also been developed for the US Marine Corps as an unmanned remote control helicopter for resupply missions into dangerous landing zones. Kaman was also a musician, and founded the Ovation guitar company.

January 31, 2002 – The death of Francis “Gabby” Gabreski. Born Franciszek Gabryszewski on January 28, 1919 in Oil City, Pennsylvania, Gabreski was the top scoring American ace in Europe in WWII, where he flew the Republic P-47 Thunderbolt and recorded 28 victories before ending the war as a German POW. After WWII, Gabreski served in the Korean War, where he scored 6.5 kills flying a North American F-86 Sabre, bringing his all-time total to 34.5 and making him one of seven US pilots to become an ace in both wars. After Korea, Gabreski served 15 more years in the USAF and commanded three different fighter wings. He retired in 1967 at the rank of colonel after 26 years of service having logged more than 5,000 hours in the air, with 4,000 of those flying jets.

January 31, 1966 – The launch of Luna 9, an unmanned spacecraft sent to the Moon as part of Russia’s Luna program to orbit and land on the lunar surface. When Luna 9 made a soft landing on the Moon on February 3, 1966, it became the first spacecraft to touch down safely on any planetary body other than Earth. Once Luna 9 became operational, it beamed back nine images of the lunar surface, including five panoramas. The Russians did not release the images immediately, but British scientists recognized and intercepted the signals being sent from the Moon and published the images around the world. While the only scientific instrument on Luna 9 was a radiation detector, the landing did demonstrate that the surface of the Moon could support a lander.

January 31, 1961 – The launch of Mercury-Redstone 2 with Ham the Chimp on board. As part of the American Mercury space program, Ham, whose name is an acronym for Holloman Aerospace Medical Center at Holloman AFB in New Mexico, was trained to do simple tasks to assess a human’s ability to function safely in space. Ham was launched from Cape Canaveral on a suborbital flight, and he performed his tasks flawlessly before splashing down in the Atlantic Ocean. After his flight, Ham lived for 17 years in the National Zoo in Washington, DC. Following Ham’s death, initial plans were to have his body stuffed and put on display as the Russians had done with their space dogs. However, Ham’s remains, minus his skeleton, were buried at the International Space Hall of Fame at Alamogordo, New Mexico.

January 31, 1958 – The launch of Explorer 1, the first satellite placed in orbit by the United States. Explorer was launched as part of the International Geophysical Year, a project that attempted to open a scientific dialogue between the East and West during the Cold War. Following the successful launch of the Russian satellites Sputnik 1 and Sputnik 2, Explorer 1 was launched from Cape Canaveral and was the first spacecraft to confirm the existence of the Van Allen radiation belt. Explorer 1 continued to return useful data for nearly four months until its batteries gave out, and it stayed in orbit until 1970. Explorer 1 was the first of more than 90 missions for the ongoing Explorers series.

Short Takeoff

If you enjoy these Aviation History posts, please let me know in the comments. And if you missed any of the past articles, you can find them all at Planelopnik History. You can also find more stories about aviation, aviators and airplane oddities at Wingspan.