Welcome to This Date in Aviation History, getting of you caught up on milestones, important historical events and people in aviation from February 23 through February 26.

February 24, 1940 – The first flight of the Hawker Typhoon. The Hawker Hurricane was one of two British fighters that beame a symbol of the Battle of Britain, a 1930s-era fighter design that fought with great effectiveness throughout the war. Though it wasn’t able to tussle with the high-flying German fighters, it proved quite effective against low-flying German bombers. The Hurricane took its maiden flight in 1935, but even before it entered production in 1937, Hawker and famed engineer Sydney Camm, who had designed the Hurricane, had already begun work on a more powerful successor.

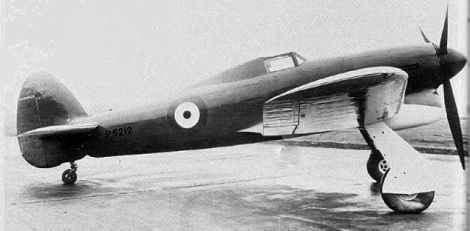

Camm worked with two basic designs, both bearing a family resemblance to the Hurricane, though somewhat larger. One reason for the increase in size was to accommodate a massive engine, the Napier Sabre. The Sabre produced up to 3,500 hp in its later versions, and would become one of the most powerful inline piston engines in the world. By 1938, Hawker was ready to proceed with the development of a prototype following the receipt of Air Ministry Specification F.18/37 which called for a fighter with a top speed of at least 400 mph at 15,000 feet using a British-built engine, and accommodations for no fewer than twelve .303 Browning machine guns.

Not only did the Typhoon bear an outward resemblance to the Hurricane, it shared many of the same construction techniques of its predecessor, as well a relatively thick wing. While the wing provided excellent strength, its thickness led to significant drag at high speeds, and also affected high altitude performance and climb rate. All of this led to a fighter that was ultimately unable to counter the high-flying German Focke-Wulf Fw 190. As a result, the mission of the Typhoon changed from that of a high-altitude interceptor to a low-level interceptor, a switch which played to the strengths of the Typhoon. Like the Hurricane before it, the Typhoon became a specialized bomber killer, flying high enough to attack the bombers from above, and having the speed and hitting power to knock them out of the sky.

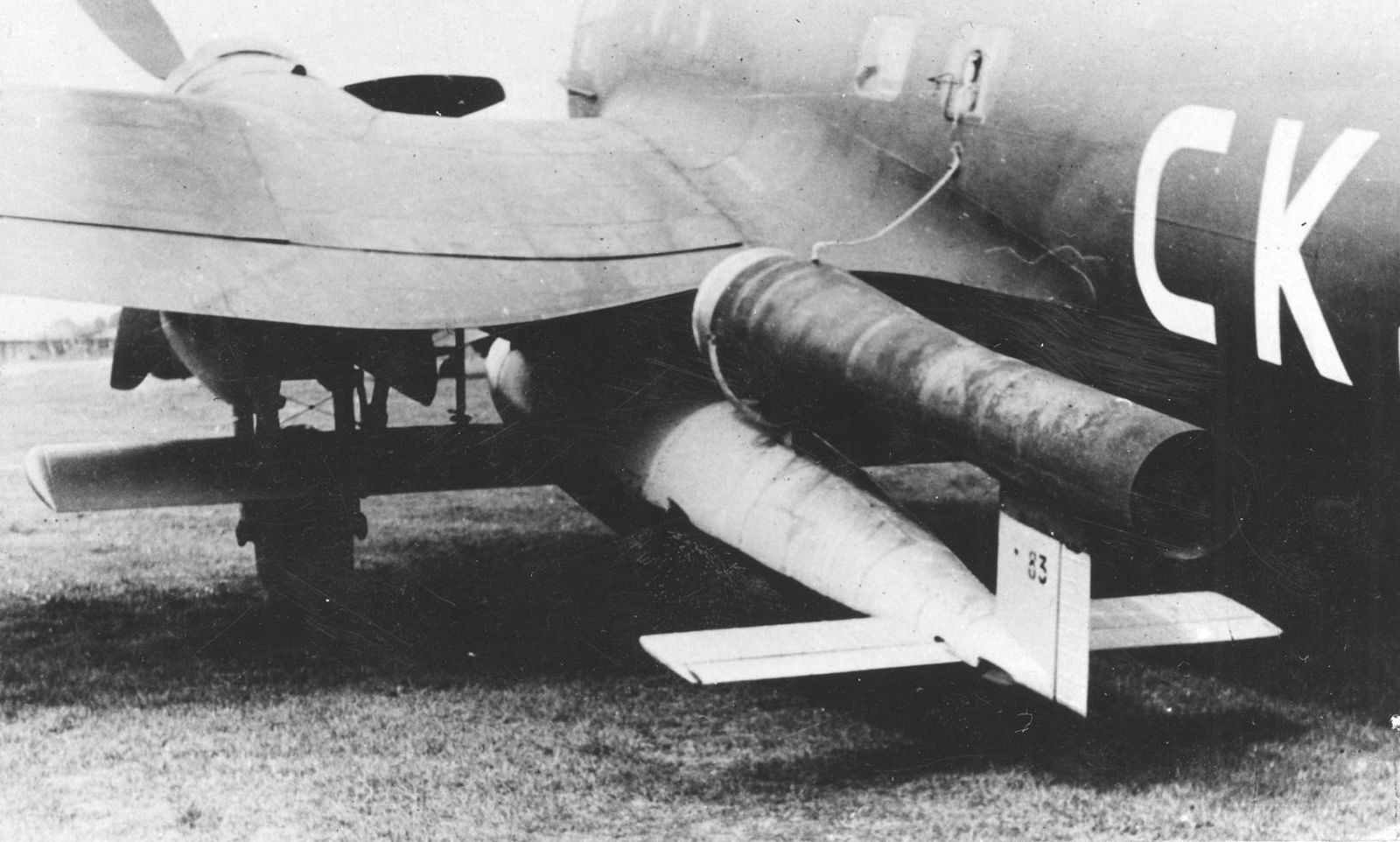

As the war in Europe progressed, the Typhoon matured as well, and truly became a work in progress. As the needs of the RAF changed, the Typhoon changed with it, and many new features and redesigns made their way into production or as retrofits in the field. The original solid cockpit with side door and cranking window gave way first to a clear canopy with added rearward visibility, then to a bubble canopy. The 12 machine guns gave way to four 20mm cannons, and provisions were made to carry greater external loads. Having proven itself an effective interceptor, the Typhoon found its true calling as a devastating ground attack aircraft, one of the most potent of WWII. Already potent with its cannons, the Typhoon was capable of carrying two 1,000 pound bombs, earning it the nickname “Bombphoon.” The addition of rockets to the Typhoon’s arsenal made it a potent tank killer in the hands of a skilled pilot, and switching between the two loads in the field was expedited by exchangeable racks. With wing-mounted drop tanks, Typhoons could 1,000 miles from bases in the Netherlands and Belgium to hit enemy targets deep in France.

Following the war, Typhoons were quickly relegated to the scrap pile, and it was thought that not a single example of the more than 3,300 aircraft produced survived the axe. However, a single aircraft was discovered in a crate in the collection of the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum. Following a trade for a Hawker Hurricane, the sole remaining Typhoon now resides in the collection of the Royal Air Force Museum London.

February 24, 1935 – The first flight of the Heinkel He 111. The Armistice of November 11, 1918 ended the First World War, and the negotiations between the victors and the vanquished resulted in numerous treaties, the most famous of which was the Treaty of Versailles, negotiated between the Allied Powers and Germany. Not only did the treaty force Germany to accept the blame for starting the war, it also contained many provisions that were intended to prevent Germany’s future capability to wage war, including a prohibition on the construction of military aircraft. But once Adolf Hitler assumed the office of German Chancellor in 1933, he immediately set about secretly rebuilding the German Luftwaffe. New pilots were trained in Russia, and new bombers were designed ostensibly as civilian airliners.

The Heinkel He 111 traces its development back to the early 1930s, when Ernst Heinkel, head of Heinkel Flugzeugwerke, was working on what he hoped would be the world’s fastest passenger plane. Two of his designers, the twin brothers Siegfried and Walter Günter, developed the Heinkel He 70 Blitz, a 4-passenger, single engine aircraft with elliptical wings, and the Blitz, as its name implies, was indeed fast and set numerous speed records. But in order to compete with American aircraft such as the Boeing 247 and Douglas DC-2, Heinkel needed a larger aircraft. So he had the Günter brothers develop a twin-engine version of the Blitz, which was called the Doppel-Blitz (Double Blitz). It was this aircraft that would serve as the basis for the wartime He 111. Development of the He 111 continued under civilian registrations, and the first prototype was recognized as “the fastest passenger aircraft in the world” when its speed exceed 250 mph. Ultimately, Lufthansa operated 12 He 111s on routes throughout Europe and even as far as South Africa.

Following the German design ethos of the time, the He 111 was powered by a pair of inverted, liquid-cooled engines, in this case the Junkers Jumo 211 V-12, which gave the bomber a top speed of 273 mph. In its military guise, defensive machine guns were mounted in the nose and in dorsal and ventral blisters, and up to 4,400 pounds of bombs could be carried internally. Using external hard points, nearly 8,000 pounds of bombs could be carried, but this made the 111 so heavy that it required rockets to assist with takeoff. Where the original doppel-blitz had a traditional stepped canopy, the later versions of the He 111 received the iconic bullet-shaped nose that made the bomber instantly recognizable.

The 111 flew its first combat missions during the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939), a conflict which served as a testing ground for Germany’s burgeoning air force and as a means of developing the tactics of combined operations of aircraft and ground troops. Flying in support of the fascist Nationalist government, the He 111 became famous (or infamous) for the bombing of the city of Guernica, one of the first times bombs were dropped on a defenseless civilian population. Based on experiences in Spain, and the ability of the He 111 to outrun all Spanish fighters of the time, Heinkel believed that the minimal defensive armament on the 111 would be sufficient in the looming war. However, during the Battle of Britain in 1940, the He 111 began to show its vulnerability. Though fast when it was first built, it was no match for the faster British fighters, nor was it very maneuverable. And its light defensive armament made it a relatively easy target for British guns.

But, with no new bomber to take its place, the He 111 soldiered on, and served throughout the war on all fronts, though it was essentially obsolete by 1942. Nevertheless, the He 111 was constantly upgraded and modified until production ended in 1944, and it proved to be an extremely versatile aircraft. The 111 served as a torpedo bomber, troop transport, reconnaissance aircraft, pathfinder (target marker), and glider tug. It was even modified to carry out aerial launches of the V-1 flying bomb. Ultimately, more than 6,500 civilian and military 111s were produced and, following the war, an upgraded version of the He 111 continued to be built under license in Spain as the CASA 2.111. Powered by Rolls-Royce Merlin engines, some of these aircraft operated into the early 1970s.

February 25, 1965 – The first flight of the McDonnell Douglas DC-9. The period following WWII was one of rapid technological development, as piston engine technology began to give way to emerging jet engine technology. In 1952, the British manufacturer De Havilland was the first to produce a jet-powered airliner with the Comet, but other manufacturers clung to the proven radial engines of WWII. Others began to implement the turboprop engine, which was, in some ways, the best of both worlds. By the 1960s, de Havilland, Boeing and Douglas had all fielded large four-engine airliners powered by either turbojets or turbofans. Douglas’ entry into that category was the DC-8, which entered service in 1959 with Delta Air Lines and United Airlines.

While the large four-engine airliners were efficient at hauling lots of passengers to far-flung destination, the growth of the hub-and-spoke system meant that airlines needed smaller planes to bring passengers from the spokes into the hub. Douglas had already begun to investigate such an airliner with their Model 2067, which was basically a smaller version of the DC-8, but the airlines were not interested and Douglas dropped the idea. In 1960, Douglas entered into an agreement with Sud Aviation of France to sell and support the twin-engine Caravelle in the US, but when orders for the Caravelle didn’t materialize, Douglas decided to forge ahead on its own. Thus, it is likely no coincidence that, when the design of the DC-9 was finalized in 1962, it bore a strong resemblance to the Caravelle. The placement of the engines on the rear of the aircraft allowed for a clean, efficient wing which was better suited to lower-speed takeoffs and landings, and it also helped limit the ingestion of debris into the engines.

With the DC-8, Douglas had been slow to offer a stretched version of the airliner, a decision that hurt sales in their competition with the Boeing 707. That mistake was not repeated with the DC-9. Douglas planned from the beginning that the airliner would be the first in a series of aircraft, and they quickly followed the initial DC-9-10 with the successively larger -20, -30 and -40 variants, with the final -50 variant taking its maiden flight in 1974. With each successive variant, the airliner gained a longer fuselage, more seats, more powerful engines, and larger wings. The initial production version of the DC-9-10 was powered by a pair of Pratt & Whitney JT8D low-bypass turbofan engines and seated 90 passengers in a one class configuration. The -30, -40 and -50 variants saw passenger capacities increase to 115, 125, and 139 passengers respectively. The maximum takeoff weight (MTOW) of 82,000 lbs for the -10 was steadily increased to 121,000 lbs for the -50. But Douglas wasn’t done yet.

Following the -50 series, continued development of the DC-9 resulted in the McDonnell Douglas MD-80 and the MD-90 series (Douglas had merged with McDonnell in 1967) and, after McDonnell Douglas and Boeing merged in 1997, the Boeing 717, a variant that was closer in size to the earlier DC-9-30. Production of the DC-9 ended in 1982 after the completion of 976 airliners, but production of the entire series that started with the DC-9 ended in 2006 after 41 years with the final Boeing 717 delivered to AirTran Airways. In addition to its commercial service, the DC-9 was also flown by the US Air Force as a medical evacuation aircraft designated the C-9A Nightingale, and with the US Navy and Marine Corps as the C-9B Skytrain II. Delta Air Lines was the last major US carrier to retire the venerable DC-9 in 2014, and only a handful remain in service today, and the MD-80 and MD-90 are starting to be phased out as well in favor of newer, more fuel-efficient airliners. Only four airlines continue to fly the 717.

For plane spotters, it can be difficult to differentiate between the major variants of the series of twinjets that began with the DC-9. But there are some specific characteristics to aid in identification.

- DC-9 series: Short fuselage, no strakes under the cockpit, pointy tail. (The last DC-9 variant, the DC-9-50, was equipped with strakes, but it retained the cone-shaped tail.)

- MD-80 series: Longer fuselage, strakes under the cockpit, pinch tail, skinny engines.

- MD-90 series: Longer fuselage, strakes under the cockpit, pinch tail, fat engines.

- Boeing 717: Shorter body, no strakes under the cockpit, pinch tail, fat engines.

Basically, you can tell the DC-9 from the B717 by the tail cone, and the MD-80 series from the MD-90 series by the size of the engines.

Short Takeoff

February 23, 2008 – A Northrop Grumman B-2 Spirit bomber crashes at Andersen Air Force Base in Guam. The B-2 Spirit belonging to the 393rd Bomb Squadron, 509th Bomb Wing based at Whiteman Air Force Base in Missouri experienced an uncommanded 30-degree nose-high pitch up during takeoff which led to the stall and crash of the $1.4 billion bomber. Both crew members ejected; the pilot was uninjured, but the co-pilot suffered a spinal compression fracture from the ejection. The cause of the crash was traced to moisture that had collected in the air data sensors following a night of heavy rain which gave the flight computer incorrect altitude and windspeed data. It remains the only crash of the B-2 bomber, and the most expensive write off in the history of the US Air Force.

February 23, 1951 – The first flight of the Dassault Mystère, a fighter-bomber built by the French firm Dassault as a swept-wing development of the earlier Dassault Ouragan. Prototypes of the Mystère were powered by an upgraded Rolls-Royce Tay centrifugal-flow turbojet in place of the Ouragan’s Rolls-Royce Nene, while production models of the Mystère were powered by a SNECMA Atar 101 axial-flow turbojet. Armed with two 30mm cannons, rocket pods, and up to 2,000 pounds of bombs, the Mystère entered service with the French Air Force in 1954, though it never saw combat. Nevertheless, the Mystère was an important step in the development of modern French jet fighters.

February 23, 1934 – The first flight of the Lockheed Model 10 Electra. Lockheed’s first twin-engine, all-metal monoplane airliner was developed from the single engine Lockheed Model 9 Orion to compete with the Boeing 247 and Douglas DC-2. The Model 10 suffered from early problems with stability which were eventually solved by a brilliant young engineer named Clarence “Kelly” Johnson, who would go on to head Lockheed’s famous Skunk Works. Following the US ban on single-engine passenger aircraft, the Electra became one of the more popular new aircraft with the budding airline industry. Many Electras were also flown by private pilots, including Amelia Earhart. Earhart was flying an Electra when she disappeared during her attempt to circumnavigate the globe. A total of 149 Model 10s were produced.

February 24, 1989 – The forward cargo door blows off of United Airlines Flight 811 in flight. UAL 811 was a regularly scheduled Boeing 747 flight that took off from Honolulu, Hawaii bound for Auckland, New Zealand. While climbing to cruising altitude and passing between 22,000 and 23,000 feet, the forward cargo hatch blew off after it closed improperly by the ground crew. As the door departed the aircraft, it took a large section of the cabin wall with it, and the ensuing explosive decompression caused the floor to buckle and sucked ten seats and eight passengers out of the aircraft. The ensuing investigation found that damaged locking pins on the door gave a false reading of the door’s being shut properly. Both United and the ground crew were faulted, and Boeing redesigned the locking mechanism.

February 24, 1955 – The first flight of the CIM-10 BOMARC missile, a long-range supersonic surface-to-air missile fielded by the United States during the Cold War for the defense of North America against attacking nuclear bombers. The BOMARC (an acronym of Boeing and Michigan Aerospace Research Center) had an operational radius of 200 miles, was designed to fly at Mach 2.5-2.8 at 60,000 feet, and could be armed with either a conventional or nuclear warhead. The USAF ultimately set up 16 BOMARC sites armed with 56 missiles each. With the arrival of the intercontinental ballistic missiles, attacking bombers were no longer perceived as a threat, and the BOMARC was retired in 1972.

February 25, 1990 – Smoking is banned on all US domestic flights. Consumer protection advocate Ralph Nader was the first to call for a smoking ban on US airlines, and United Airlines was the first to implement a separate smoking section on their airliners in 1971. By April 1988, a smoking ban was instituted on flights of two hours or less and, by 1990, smoking was banned on all domestic flights of six hours or less. Ten years later, the ban was further extended to all domestic and international flights. Smokers who violate the ban face a fine of up to $500 or 10 days in prison. Initially, pilots were allowed to continue smoking on the flight deck due to safety concerns over the effects of nicotine withdrawal in chronic smokers, though the FAA extended the smoking ban to the flight deck in 1992. The use of E-cigarettes, or “vaping,” is also prohibited.

February 25, 1978 – The death of Daniel “Chappie” James, Jr, a USAF fighter pilot and the first African American to attain the rank of four-star general. James served as a flight instructor for the 99th Pursuit Squadron of the Tuskegee Airmen, but saw no combat in WWII. In Korea, James flew 101 combat missions in the North American P-51 Mustang and Lockheed F-80 Shooting Star, and then flew 78 combat missions in Vietnam. Most of those missions were in the dangerous areas of Hanoi and Haiphong Harbor, and included one mission he led whose pilots claimed seven MiG-21 kills, the highest for a single sortie in the war. After achieving the rank of General, James was named commander in chief of NORAD, where he held operational command of all strategic aerospace defenses of the US and Canada. James died of a heart attack on February 25, 1978, just three weeks after his retirement from the US Air Force.

February 25, 1963 – The first flight of the Transall C-160, a twin-turboprop military transport and cargo aircraft developed as a joint venture between Germany and France. “Transall” is an acronym for Transporter Allianz, and the C-160 was developed to satisfy requirements that arose in the late 1950s for a new transport aircraft to replace the Nord Noratlas. The Transall consortium was formed in 1959 and, following a delay in production while Lockheed unsuccessfully marketed the Lockheed C-130 Hercules to Germany, the first production aircraft were delivered in 1967. A total of 214 were built between 1965-1985, and the C-160 has since become one of a handful of aircraft to see over 50 years of service.

February 25, 1933 – The launch of the USS Ranger (CV-4), the first US Navy ship to be designed from the keel up as an aircraft carrier. Similar to the Navy’s first carrier, USS Langley (CV 1), which had been converted from a collier, Ranger was not designed with an island superstructure, though one was added later. Since Ranger was too slow to keep pace with more modern carriers plying the Pacific Ocean, she served in the Atlantic and provided air support for the landings in North Africa during Operation Torch in November 1942. In 1943, Ranger participated in raids against German shipping in the North Atlantic as part of Operation Leader, and served as a training carrier late in the war. Ranger decommissioned in 1946 and scrapped the following year.

February 26, 1979 – Production of the Douglas A-4 Skyhawk ends. With delivery of an A-4M Skyhawk II to Marine Squadron VMA-331, Douglas closed the book on 25 years of production of one of the most versatile attack jets ever to serve the US Navy and Marine Corps. Designed as a replacement for the Douglas AD (A-1) Skyraider, the Skyhawk was a small yet powerful jet capable of delivering both conventional and nuclear weapons and, despite its diminutive size, the A-4 could carry a heavier payload than a B-17 Flying Fortress. Known to its pilots as the Bantam Bomber, Mighty Mite and Scooter, the Skyhawk was also nicknamed Heinemann’s Hot Rod after its designer Ed Heinemann and in homage to its excellent performance. The A-4 entered service in 1956 and first saw combat over Vietnam in 1964. Until the arrival of the LTV A-7 Corsair II, the Skyhawk served as the Navy’s primary ground attack aircraft, though the Marines continued to fly their Skyhawks. After retirement from fleet duty in 1991, the Skyhawk found a new lease on life as an adversary aircraft at the Navy’s Fighter Weapons School (commonly called Top Gun). The A-4 was chosen as the bandit aircraft because of its small size, excellent maneuverability and smokeless trail, often playing the role of the MiG-17. The Blue Angels also flew the Skyhawk from 1974 to 1986. The last operational A-4s were retired in 2003. When production ended, Douglas had delivered a total of 2,960 copies of the plucky attacker in a host of variants.

February 26, 1937 – The first flight of the Fiat G.50 Freccia, a single-engine fighter flown by the Italian Air Force (Regia Aeronautica) in WWII and Italy’s first single-seat all-metal monoplane. It was also the first Italian aircraft to enter production with retractable landing gear and an enclosed cockpit. The Freccia (Arrow) was powered by a 14-cylinder Fiat A.74 radial engine and, with a maximum speed of 292 mph, was considered quite fast for its day. It was also highly maneuverable, but suffered from a lack of firepower provided by its pair of 12.7mm machine guns. The Freccia first saw service in the Battle of Britain, but it was far outclassed by more modern fighters. They were somewhat more successful fighting in the Mediterranean, but the type found its greatest success in the hands of Finnish pilots, who enjoyed a 33/1 kill ratio against Russian fighters.

Connecting Flights

If you enjoy these Aviation History posts, please let me know in the comments. And if you missed any of the past articles, you can find them all at Planelopnik History. You can also find more stories about aviation, aviators and airplane oddities at Wingspan.