Welcome to This Date in Aviation History, getting of you caught up on milestones, important historical events and people in aviation from March 2 through March 5.

March 2, 1969 – The first flight of the Aérospatiale/British Aircraft Corporation Concorde. The evolution of the airplane has branched out in many directions, and the airplane has taken many forms, but perhaps one constant throughout its developmental history has been the quest for ever greater speed. In 1903, the Wright Brothers’ first flight covered the ground at a speed of 6.8 mph, but a mere 44 years later Chuck Yeager piloted the Bell X-1 past the speed of sound. In Yeager’s day, supersonic flight was mainly the purview of the world’s militaries, and it remains so to this day. Nevertheless, aircraft designers were keen to see how supersonic technology might be applied to commercial aircraft, and the English and French each worked individually on their own solutions.

In the early 1950s, the Royal Aircraft Establishment in England formed the Supersonic Transport Aircraft Committee to study the concept of a supersonic airliner. After considerable research on various design possibilities, they settled on an ogee delta planform for the wing, with a slender fuselage to reduce drag. Their work culminated in the Bristol Type 223, an airliner that would have seated about 100 passengers with a top speed of Mach 2, though it never progressed beyond the design phase. Across the English Channel, the French were also investigating a supersonic airliner, and had come to many of the same design conclusions reached by the British. However, their concept for the Super-Caravelle, while similar in shape, was significantly smaller, and was envisioned more as a replacement for the Caravelle airliner and not for transatlantic flights.

With both countries working towards much the same goal, it became clear that an international partnership would best serve their interests, and help compete against the US dominance in commercial airliner production. Boeing had already begun initial investigation of their own into building an SST. In November 1963, the United Kingdom and France signed a treaty binding the two countries to work together on the project, and the name Concorde was chosen in honor of this landmark international agreement. Construction of two prototypes began in 1965, the first in France (001) and the second in England (002). The French Concorde flew first on March 2, 1969, followed a month later by the English Concorde on April 9, 1969. Ultimately, 20 Concordes were built, six of which were prototypes and used for development and testing. Air France and British Airways each received seven aircraft.

Concorde entered service with British Airways on January 21, 1976 flying between London and Bahrain while Air France pioneered supersonic passenger service between Paris and Rio de Janeiro. British Airways flew daily between New York and London, and weekly flights to Barbados during the holiday season. They also served Dallas, Miami, Singapore, Toronto, and Washington, DC. Air France flew between Paris and New York five times a week, as well as scheduled flights to Caracas, Mexico, Rio, and Washington, DC. Concorde’s four Rolls Royce/Snecma Olympus 593 afterburning turbojets provided a maximum cruising speed of Mach 2.04, and an average flying time of three-and-a-half hours cut the time between transatlantic destinations in half when compared to traditional airliners. Concorde set a number of records, including the fastest eastward transatlantic flight when an SST departed on February 7, 1996 from New York’s JFK International and touched down at London Heathrow in just 2 hours, 52 minutes, 59 seconds. Concorde also set records for circumnavigation of the globe in both directions, though with numerous refueling stops along the way.

The 14 operational Concordes enjoyed an exceptional safety record, though there were two non-fatal accidents and a spate of tire failures throughout their service history. The only loss of a Concorde occurred on July 25, 2000 when Air France Flight 4590 (F-BTSC) crashed shortly after takeoff from Charles de Gaulle airport when debris on the runway punctured a tire and ruptured the fuel tank. The burning airliner crashed into a hotel, killing all 109 passengers and crew along with four persons on the ground. Following the crash, all Concordes were grounded until safety improvements could be made, and service resumed in November 2001. Though the crash didn’t lead directly to the end of Concorde flights, its service days were numbered. The accident led to a drop in bookings for flights on Concorde at a time when all passenger numbers were down following the September 11 terrorist attacks. Concorde’s high fuel costs and small passenger capacity meant that the SST had never been a money-maker for the airlines and, with rising maintenance costs also figuring into the balance sheet, Air France and British Airways made the decision to retire Concorde in 2003. Twelve of the original 14 operational aircraft were dispersed to display sites in Europe, the US, and Barbados. Of the remaining two, one aircraft was lost in the 2000 crash, and the other was used for spare parts and scrapped in 1994.

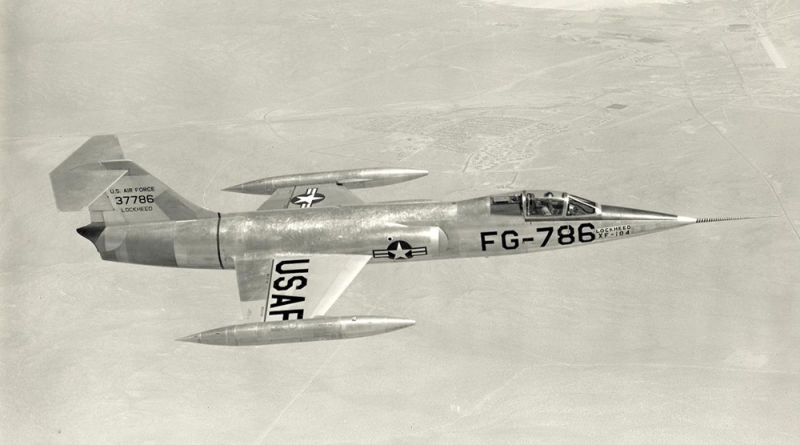

March 4, 1954 – The first flight of the Lockheed F-104 Starfighter. When the first jet fighters appeared during WWII, they were built with the prevailing technology of WWII, and that meant straight wings. But when troves of data on the benefits of swept wings were captured from the Germans near the end of the war, the swept wing quickly became a standard design element of jet fighters going forward. Delta wings, another design element pioneered by the Germans, were also adopted. But if anybody was going to buck that trend, it was Lockheed’s Clarence “Kelly” Johnson, perhaps America’s greatest aircraft engineer and one who became famous—or infamous—for doing things his way.

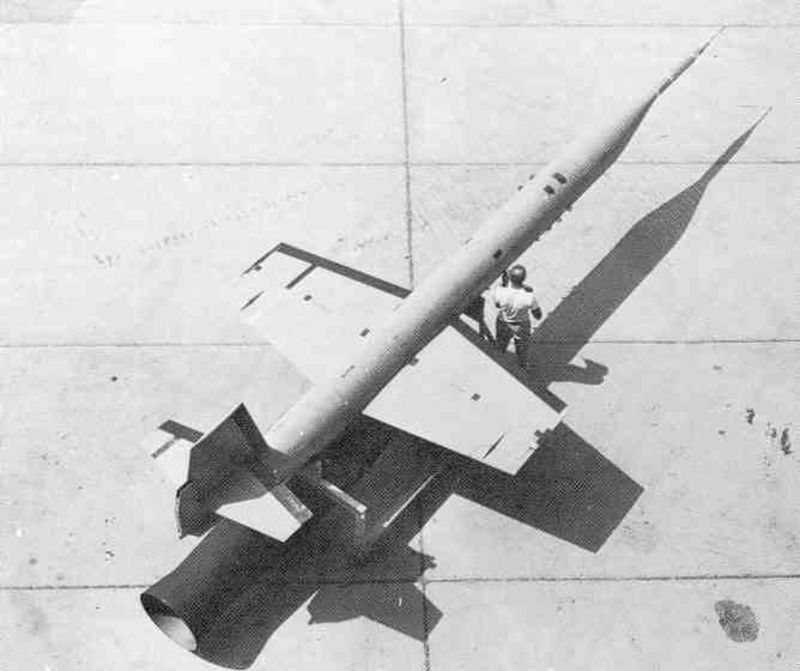

During the Korean War, American pilots came face to face with smaller, more nimble Russian fighters like the MiG-15. While the Americans ultimately prevailed, due in large part to better training and more experienced pilots, it was a much closer fight in the early part of the war. In 1951, Kelly Johnson traveled to Korea to interview US pilots and ask them directly what they wanted to see in a new fighter. Most said they wanted something smaller, faster, and more maneuverable. So Johnson, never one to do things in half measures, envisioned a very small fighter wrapped tightly around a single powerful engine that could race at Mach 2 in level flight. For the all-important wings, Johnson eschewed the traditional swept or delta wings in favor of minimal, trapezoidal wings that bore a striking resemblance to the wings of the experimental Lockheed X-7 missile under development at the time. Johnson also gave the wings a slight anhedral, or downward angle, to help counteract potentially deadly inertia coupling. High-pressure air was also blown over the flaps on landing to help decrease landing speeds. Where the wings of contemporary aircraft were used to house fuel or landing gear, the wings of the Starfighter were razor thin, so thin in fact that the leading edges were covered with a felt cap to protect the ground crews who serviced the fighter. Not all of Johnson’s ideas were winners. Early Starfighters were given a downward-firing ejection seat over concerns that pilots would not clear the T-tail, though this questionable arrangement was changed to a standard upward firing ejection seat in subsequent models.

The Starfighter moved from contract to first flight in less than one year, but development of the new fighter proved difficult, and it was four years before the first Starfighters entered service with the USAF. Then, just three months later, all F-104s were grounded because of engine problems and a series of accidents. The F-104A also suffered from a lack of all-weather capability and short range and, after only one year of frontline Air Force service, the A model was passed to units of the Air National Guard or repurposed as the unmanned QF-104 target drone. Lockheed responded to these shortcomings with the F-104C, which added an improved fire control radar and capacity for more ordnance, and the Air Force sent the Starfighter to Vietnam. Though it served two tours, F-104 pilots claimed no victories over enemy aircraft while losing 14 of their own aircraft in the process. By this time, the Air Force had lost interest in the Starfighter, and that could have been the end of the road for Johnson’s innovative little fighter.

The Starfighter won a reprieve from the scrap pile in 1959 when a group of European countries led by Germany decided to procure the F-104 as a multi-mission attack fighter to replace older aircraft in service. The selection was controversial, though, and accusations that Lockheed bribed the European officials to accept the Starfighter dogged the decision. The F-104G (G for Germany) was built under license by Canadair and by a consortium of European companies including Messerschmitt/MBB, Dornier, Fiat, Fokker, and SABCA. Dubbed the Super Starfighter, it had a strengthened fuselage and wing, increased fuel capacity, enlarged fin and redesigned flaps for combat maneuvering. And, unlike the original F-104, which sacrificed a fire control radar to save space and weight, the F-104G was fitted with a radar as well as an inertial navigation system, the first on any production fighter. Despite these improvements the F-104G service with Germany was not without problems, particularly with wing strength and pilot workload, and it was not popular. Nevertheless, the F-104G made up the bulk of all Starfighters produced, with 1,122 out of a total of 2,578 built by the European consortium. Though the US Air Force was done with the Starfighter by 1969, it served in Europe for another 10 years, with the final variant, the Aeritalia F-104S, serving until 2004.

March 4, 1936 – The first flight of the Hindenburg (LZ 129). Though the airplane gets much of the attention for helping mankind slip the surly bonds of earth, it was a balloon that first carried a man into the air on November 21, 1783, when the Montgolfier brothers flew their hot air balloon over France. Less than two months later, Jacques Charles and the Robert Brothers, again in France, flew the world’s first hydrogen balloon, not only ascending to a then unheard of altitude of nearly 10,000 feet, but also carrying aloft instruments to measure temperature and barometric pressure. By 1785, a hydrogen balloon made the first flight across the English Channel and, in 1852, the first powered and steerable dirigible took to the skies in France. This semi-rigid airship paved the way for huge rigid airships with metal frames housing bags of hydrogen or helium, culminating with the Hindenburg, the largest flying machine ever built.

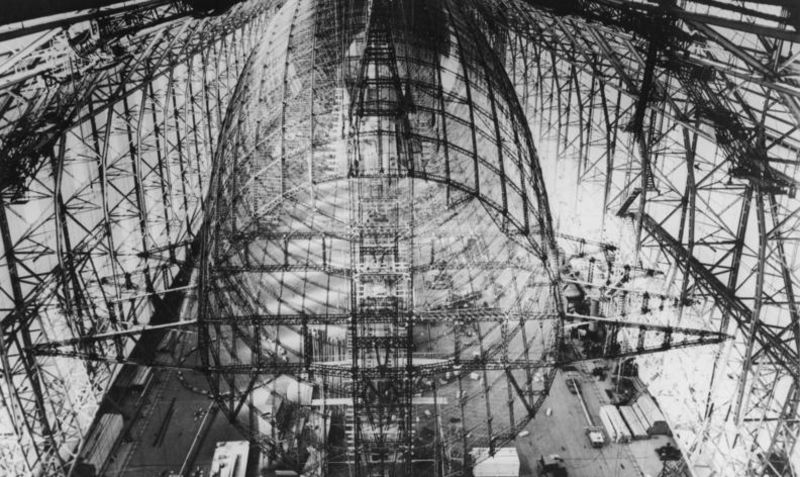

The first Zeppelin, a rigid airship named after its creator, German Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin, entered commercial service in 1910. Eventually, Zeppelins became the world’s first airliners, and transatlantic flights became commonplace. The Hindenburg, German dirigible LZ-129 (Luftschiff Zeppelin #129, registration D-LZ129), was the lead ship of the Hindenburg class. Designed and built by the Zeppelin Company (Luftschiffbau Zeppelin GmbH) and named after the late Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg, the President of Germany from 1925-1934, Hindenburg was constructed of a duralumin framework with with 16 cotton gas bags attached. The outer skin was made of cotton and doped with a reflective coating to protect the gas bags from ultraviolet and infrared radiation. Powers by four Daimler-Benz DB 602 16-cylinder engines and adorned with enormous swastikas on the tail fins, Hindenburg was as much an object of Nazi propaganda as it was a transatlantic passenger vessel.

Hindenburg was originally built to be filled with helium, but helium was rare and came at an exorbitant cost. The only source was the United States, where helium was a byproduct of natural gas mining. Construction of Hindenburg went ahead regardless, and when the US refused to lift its export ban on helium, Hindenburg’s designers made the fateful decision to switch to highly flammable hydrogen instead, even though the dangers of hydrogen were well known. Hindenburg’s first commercial flight took place on March 31, 1935, and the first of 17 transatlantic flights culminated in Lakehurst, New Jersey on May 6, 1936. Two months later, Hindenburg made a record double crossing of the Atlantic in just under six days. But despite its unparalleled speed and size, Hindenburg would become most famous not for setting records, but for the devastating crash that marked its final flight.

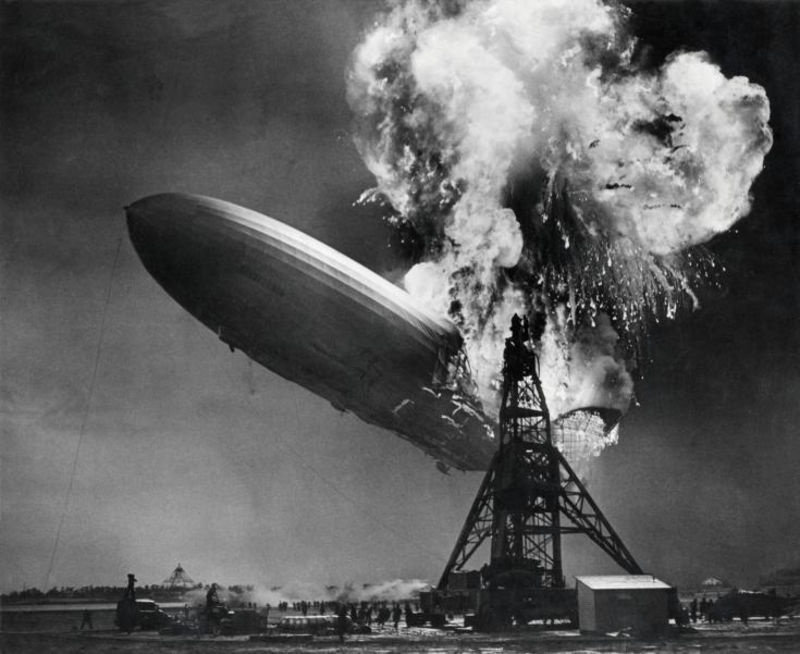

Hindenburg left Frankfurt on May 6, 1937 on a transatlantic crossing to Lakehurst. It’s arrival was initially delayed by a line of thunderstorms, but the Zeppelin was finally cleared to land at about 7:00 pm. Twenty-one minutes later, shortly after dropping mooring lines to the ground crew, Hindenburg suddenly erupted into flames and crashed. In less than thirty seconds, the massive airship was reduced to a smoldering wreck of twisted, charred metal. Thirteen of the 36 passengers died, along with 22 members of the crew of 61 along with one man on the ground. The cause of the crash remains a topic of much conjecture even to this day, and no exact cause has ever been determined. Some suspect sabotage, others suggest atmospheric conditions related to the thunderstorms in the area. One of the more plausible theories is that hydrogen gas leaking from one of the cells was ignited by static electricity. After the crash, the duralumin hulk was returned to Germany and recycled for use in the construction of Luftwaffe aircraft. Graf Zeppelin II (LZ 130), Hindenburg’s sister ship and the last great Zeppelin built by Germany, was scrapped in 1940 before its completion, and its duralumin frame was also melted down to be used for airplanes.

March 5, 1943 – The first flight of the Gloster Meteor. When the Wright Flyer took to the skies of Kitty Hawk, North Carolina in 1903, it was powered by a homebuilt 4-cylinder engine that generated 12 horsepower and turned a wooden propeller. Over the ensuing years, engines became more powerful, rotary and radial engines were introduced, and the piston-powered propeller plane reached its zenith by the late stages of WWII. But the years before the war also witnessed the development of an entirely new powerplant, one that would take the airplane from the Wright Brother’s six miles per hour to beyond the speed of sound. As England’s first operational jet fighter, the Gloster Meteor is inextricably linked to the story of the jet engine.

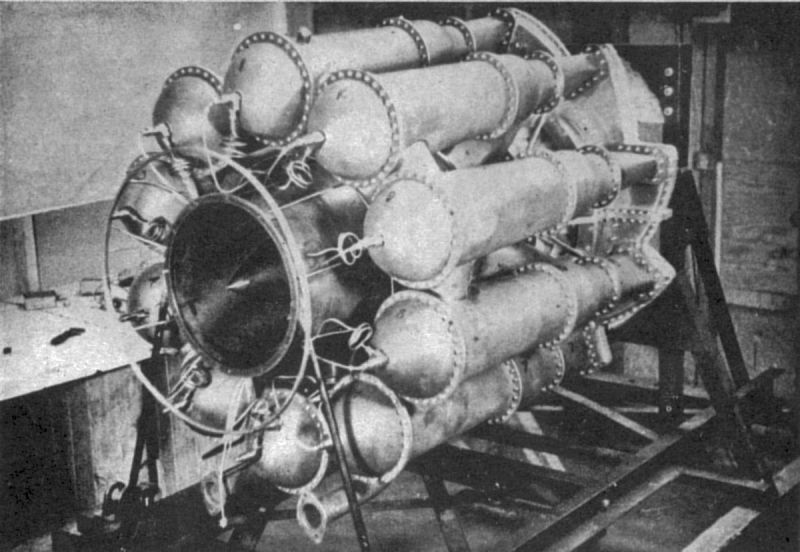

With the arrival of operational jet fighters late in WWII, the development of the turbojet engine is often associated with that conflict. However, the origins of the jet engine can be traced back to well before the war began. The Germans fielded the first operational jet fighter with the Messerschmitt Me 262, but work on a jet engine in England had begun by the late 1920s. Royal Air Force engineer Sir Frank Whittle had been working on the principle of a motorjet, where a piston engine is used to drive a compressor. Whittle’s breakthrough came when he thought of replacing the piston engine of the motorjet with a turbine, and he patented his first design in 1930. By 1936, he had formed his own company, Power Jets Ltd, to continue work on his concepts. Though he found it difficult to find financial backers for his project, and hard to find anybody to build a plane to test the new engine, Whittle eventually visited the Gloster Aircraft Company in 1939. There he met Gloster’s chief engineer, George Carter, who took an interest in Whittle’s engine and began work on an aircraft design in which to implement the turbojet. The first proof of concept aircraft was the Gloster E.28/39, a single-engine aircraft that took its maiden flight on May 15, 1941.

With proof that the turbojet worked, Gloster moved ahead with work on a production fighter, but decided to use two engines to make up for the lack of power in the early turbojet. By 1940, Carter had the first proposal for the twin-engine Meteor fighter, and within six months Gloster received an order for eight prototypes under Specification F9/40, which was written to match the fighter already in development. The Meteor was built in a modular fashion from five main sections: nose, forward fuselage, central section, rear fuselage, and tail sections. Various companies were contracted to build the modules, and this allowed production to be dispersed. It also facilitated disassembly and transport of the Meteor.

Following testing, the Meteor was introduced on July 27 1944, with the first aircraft delivered to No. 616 Squadron of the RAF. With a top speed of 600 mph, 100 mph faster than the Supermarine Spitfire, the Meteor was first flown against the German V-1 flying bombs that were terrorizing England. On August 4, 1944, Meteor pilots claimed their first victories when they shot down two V-1s, and they eventually claimed 14 “buzz bombs” by the end of the war. At first, Meteors were forbidden from flying over German-held territory for fear that one of the fighters would fall into enemy hands. But when the V-1 threat subsided, Meteors finally were sent to Europe in January of 1945. But a clash between the Meteor and the Me 262 never occurred.

Production and development of the Meteor continued after the war, with improvements made in the design, fuel capacity, radar and weapons systems, as well as the development of a two-seat trainer version. F8 Meteors flying with the Royal Australian Air Force saw significant action during the Korean War. Nearly 4,000 Meteors were built by the time production ended in 1955, and they were widely exported. Meteors also served as testbeds for engine development, and the first turboprop-powered aircraft to fly was a Meteor outfitted with turboprop engines. British Meteors ended their days with the RAF as target tugs, flying into the 1980s and, despite their retirement, Meteors are still providing useful service today. The Martin-Baker Aircraft Company, pioneers in ejection seat technology, still flies a pair of Meteors to perform flight tests of the latest ejection seats.

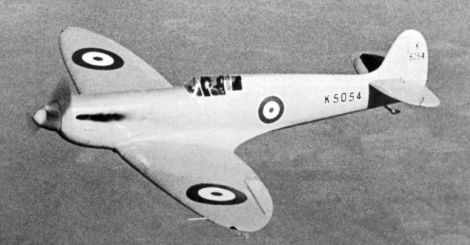

March 5, 1936 – The first flight of the Supermarine Spitfire. The years between World War I and World War II is known as the Golden Age of Aviation, a period marked by rapid advances in aircraft design and construction. Aviation grew from the sole purview of the military to include civilian pilots, air races became a world phenomenon, and prestigious trophies and prize purses became a driving force behind significant advances in speed and aerodynamic design. Supermarine had made a name for itself building racing seaplanes, and had won the Schneider Trophy three times between 1927-1931. With the prospect of war looming in Europe by the mid-1930s, the Royal Air Force turned to the Woolston-based company to develop a new fighter that could intercept and defeat faster, more advanced German aircraft.

Drawing on experience from their racing days, Supermarine first developed the Type 224, a monoplane with fixed landing gear and an open cockpit. But problems with the Rolls-Royce Goshawk engine, coupled with poor performance, led Supermarine to abandon the Type 224 for a still more modern design. What followed was the Type 300, which underwent significant subsequent development to include an enclosed cockpit, retractable landing gear, smaller wings, and an oxygen supply for the pilot. Supermarine designer R. J. Mitchell also gave the the new fighter what would become one of the Spitfire’s most recognizable features: its graceful elliptical wing, with an exceptionally thin cross section that helped increase the Spitfire’s top speed. But most importantly, Supermarine settled on the Rolls-Royce PV-12 engine, the precursor to the mighty Merlin. The Spitfire was an immediate winner. Upon landing after the first flight of the prototype, Vickers chief test pilot Capt. Joseph “Mutt” Summers reportedly said, “Don’t touch anything.”

Though the Spitfire was well-received, its Merlin engine was not without its teething problems. Unlike the fuel injected engines in use by the Luftwaffe, the Merlin had a carburetor. This made the Spitfire susceptible to flooding in a nose-over dive or inverted flight. At first, pilots learned to combat this problem by first half-rolling the aircraft before a dive. But until a permanent solution could be found with the addition of a pressurized carburetor, it was Beatrice “Tilly” Shilling who saved the day. Shilling devised a restrictor, nicknamed Miss Shilling’s Orifice, that restricted the flow of fuel to no more than the engine could use at full power. While only a stopgap measure, the restrictor kept the Spitfire flying until the new carburetors could be developed. In the final round of Spitfire production, the Merlin gave way to the Rolls-Royce Griffon which employed a pressure-injection carburetor and boasted 2,340 hp and a top speed of nearly 500 mph.

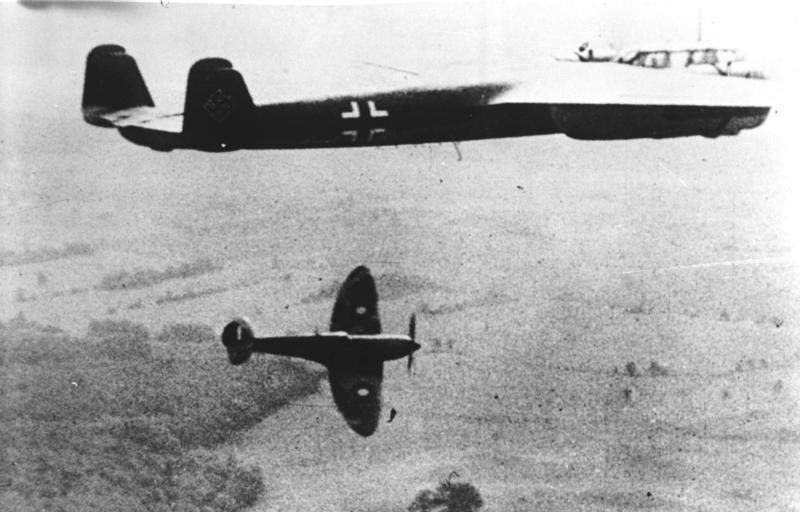

During the Battle of Britain, Spitfire pilots and their comrades flying the Hawker Hurricane faced the onslaught of the Luftwaffe. Though the less glamorous Hurricane fought in greater numbers, the Spitfire became the better known fighter of the battle, as dashing RAF fighter pilots in the “Spits” dueled with German fighters high in the sky while the “Hurrys,” which were no match for the Messerschmitt Bf 109, slugged it out with the bombers at lower altitudes. Head to head with the Me 109, the Spitfire pilot appreciated the firepower provided by eight Browning .303 machine guns. While not as powerful as the canon used by the Germans, Spitfire pilots could concentrate more firepower on the enemy.

The Spitfire was continuously improved and produced throughout the war. Supermarine developed numerous variants, including a carrier-based version which was nicknamed the Seafire, and export Spitfires were flown by 35 countries around the world. The mission of the Spitfire didn’t end with VE Day. They continued patrolling German skies after the war, Spitfire pilots flew over 1,800 sorties during the Malayan Emergency, and the final operational sortie flown by the Spitfire took place on April 1, 1954. In all, more than 20,000 Spits were produced from 1938-1948, making it the third-highest produced warplane behind the Ilyushin Il-2 Sturmovik (36,183) and the Bf 109 (34,852).

Short Takeoff

March 2, 1965 – The start of Operation Rolling Thunder, a sustained campaign of aerial bombardment against North Vietnam that lasted more than three years. US military planners hoped the bombings would boost South Vietnamese morale, stop the North Vietnamese government from its support of Communist rebels in the south, destroy the transportation system of North Vietnam, and prevent the flow of war materiel into the south. American and South Vietnamese aircraft faced dogged and sophisticated resistance to the attacks, and over 900 aircraft were lost. The US Air Force suffered the death of 255 pilots with 222 captured, while the US Navy and Marine Corps casualties totaled 454 pilots killed, captured or missing. Despite 864,000 tons of bombs dropped over the course of 300,000 sorties, Rolling Thunder was ultimately unsuccessful.

March 2, 1955 – The first flight of the Dassault Super Mystère, a French-built fighter-bomber and the first Western European supersonic aircraft to enter mass production. The Super Mystère is the ultimate evolution of the Dassault Ouragan, which had in turn been developed into the Mystère I/II/III and Mystère IV. The Super Mystère was the first in the series to achieve supersonic speeds in level flight. Following its introduction in 1957, the Super Mystère served with the French Armée de l’Air until its retirement in 1977. It was also exported to Honduras and Israel, where it saw action in the Six Day War and the Yom Kippur War. A total of 180 aircraft were built.

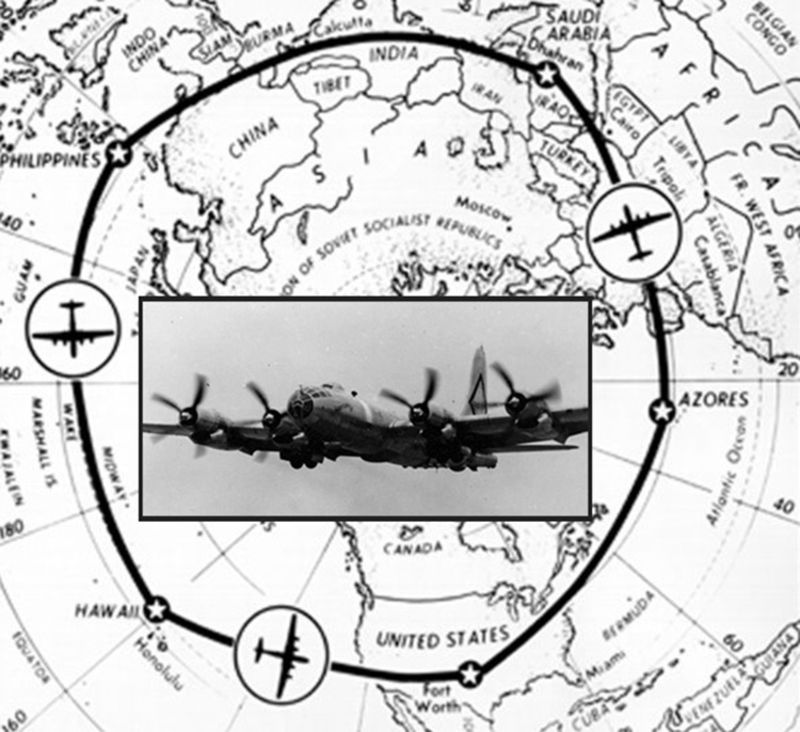

March 2, 1949 – The crew of Lucky Lady II completes the first non-stop circumnavigation of the globe. Lucky Lady II was a US Air Force Boeing B-50 Superfortress belonging to the 43rd Bombardment Group. At the time of its round-the-world flight, the strategic bomber still had all of its defensive armament, though the bomb bay had been fitted with an additional fuel tank. Lucky Lady II departed from Carswell AFB in Texas on February 26 on an easterly route and was refueled by aerial tankers four times during a 94-hour flight that covered 23,452 miles. Two crews took turns flying six-hour shifts. For their roles in the mission, each member of the crew was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross.

March 3, 2005 – Steve Fossett completes the first nonstop solo circumnavigation of the Earth. Millionaire adventurer Steve Fossett took off from Salina, Kansas on February 28, 2005 in the Virgin Atlantic GlobalFlyer, an aircraft designed by Burt Rutan and built by Rutan’s company Scaled Composites. The twin-boom aircraft was built from carbon fiber reinforced plastic and powered by a single Williams FJ44 turbofan engine. Fossett flew eastward from Kansas at an average speed of 342.2 mph and returned to his starting point slightly more than 67 hours and 22,936 miles later to claim the absolute record for “speed around the world, nonstop and non-refueled.” The following year, Fossett piloted the GlobalFlyer 25,766 miles nonstop to set the world’s record for the greatest unrefueled distance ever traveled in an aircraft.

March 3, 1974 – The crash of Turkish Airlines Flight 981. Turkish Airlines Flight 981 was regularly scheduled McDonnell Douglas DC-10 (TC-JAV) service between Istanbul to London Heathrow that crashed when an improperly closed cargo hatch blew open at approximately 23,000 feet. When the door broke free, it caused an explosive decompression of the cabin and severed the control cables to the airliner’s tail and number two engine. All 346 passengers and crew were killed when the airliner crashed into the Ermenonville Forest in France, making it the world’s deadliest aviation crash to date. Following a similar door failure two years before on an American Airlines DC-10 that landed safely, it was discovered that flaws in the design of the door could make it appear that the door was closed properly when in fact it wasn’t. Insurance company investigators also discovered that ground crew personnel in Turkey had ground locking pins down in an effort to get the door to close. After settling in court with the victims of the crash, McDonnell Douglas completely redesigned the cargo door, and the Federal Aviation Administration mandated that similar changes be made to outward-opening cargo doors on other large airliners.

March 3, 1969 – The US Navy establishes the Fighter Weapons School at NAS Miramar, popularly known as TOPGUN. In 1968, the US Navy published the Ault Report, a review of Navy air-to-air missile system capabilities from 1965-1968, a period when US pilots suffered high losses during the Rolling Thunder campaign. Rather than place the blame for American aircraft losses entirely on early air-to-air missiles or missile systems, the Ault report recommended that an Advanced Fighter Weapons School be created to re-educate pilots in air combat maneuvering (ACM, or dogfighting), skills that had languished after the US started to rely solely on guided missiles. Select Naval Aviators and flight officers are sent to train at Topgun, then return to their operational units to share what they learned. In 1996, Topgun was merged into the Naval Strike and Air Warfare Center at NAS Fallon in Nevada.

March 3, 1915 – The National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics is created to promote the technological development of aviation in the United States. NACA was at the forefront of some of the most important advances in aircraft design, such as the NACA cowling, which improved aerodynamics of radial engines and increased fuel efficiency, the NACA duct, which was an aerodynamic air intake used on jet aircraft, and the NACA airfoil, which maximized air pressure both above and below the wing. NACA took the lead in the development of advanced jet aircraft in the period immediately following WWII, and was responsible for many of the significant advances made in speed and altitude. Orville Wright served on the board for 28 years. With the beginning of the American space program, NACA was dissolved and its assets were transferred to the fledgling National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) in 1958.

March 4, 1993 – The first flight of the Dassault Falcon 2000, a business jet developed by the French company Dassault Aviation as a smaller variant of the Dassault Falcon 900. Though the 2000 has only two engines compared to the 900's three engines, it still possesses intercontinental range. Continued development of the 2000 has brought increased fuel efficiency, extended range, and short runway capability. Dassault has also proposed a maritime reconnaissance version and, in addition to its civilian operators, the 2000 is currently flown by the militaries of France, Bulgaria, Slovenia and the Republic of Korea. The 2000 is powered by two Pratt & Whitney PW308C turbofans and is capable of speeds of Mach 0.85 with a range of up to 6,000 nautical miles.

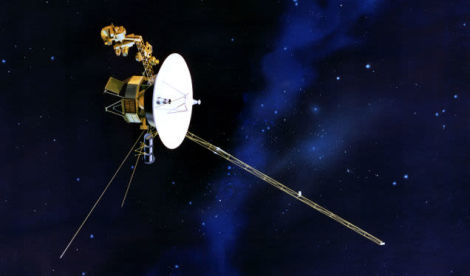

March 5, 1979 – Voyager 1 makes its closest approach to Jupiter. Voyager 1 was sent to space on September 5, 1977 on a mission to study the outer solar system. Launched 16 days after Voyager 2, Voyager 1 has operated for more than 38 years and continues to return data to Earth. After close flybys of Jupiter, Saturn and Saturn’s moon Titan, Voyager 1 continued to the boundaries of the outer heliosphere and, on August 25, 2012, it became the first spacecraft to enter interstellar space. Voyager will continue functioning until its batteries run out in 2025.

March 5, 1966 – The first free flight of the Lockheed D-21 reconnaissance drone. When Lockheed U-2 pilot Francis Gary Powers was shot down over the Soviet Union, work began on an unmanned system that could do dangerous reconnaissance work without putting a pilot at risk. The D-21 drone was inspired by the design of the Lockheed A-12, and was intended to be launched from the back of a modified A-12 known as the M-21. Captive flight tests of the drone and M-21 began in December 1964, followed by three release flights. On the fourth flight, the D-21's engine malfunctioned, and the drone struck the vertical stabilizer of the M-21 causing both aircraft to crash. One member of the M-21's two-man crew was killed. Lockheed modified the D-21 to launch from under the wing of a Boeing B-52 Stratofortress, and four reconnaissance missions were carried out over China, but all ended in failure, either with the malfunction of the D-21 or with the loss of the film that had been ejected from the drone. The D-21 project was canceled in 1973.

March 5, 1963 – A plane crash claims the life of country music singer Patsy Cline. Following a benefit concert in Kansas City, Kansas, Cline was unable to leave following the show because the local airport was fogged in. She declined an offer of a car ride to Nashville, and instead opted to fly out the next day. Cline boarded a Piper PA-24 Comanche (N-7000P) for the flight to Nashville and, after a stop for fuel in Dyersburg, Tennessee, the pilot chose to continue despite worsening weather, even though he was not qualified for instrument flying (IFR). The Comanche crashed 90 miles from Nashville, and the NTSB report cited the pilot’s loss of control in adverse conditions as the cause. Along with Cline, musicians Hawkshaw Hawkins, Cowboy Copas, and pilot Randy Hughes were killed.

March 5, 1958 – The first flight of the Yakovlev Yak-28, a Cold War era tactical bomber produced by the Soviet Union. The Yak-28 was powered by two Tumansky R-11 afterburning turbojets mounted in pods beneath 45-degree swept wings. Though designed as a tactical bomber, the Yak-28 was also used for reconnaissance, electronic warfare, as an interceptor, and as a trainer. Its NATO reporting names—Brewer (jet bomber), Fireball (jet fighter), and Maestro (miscellaneous)—reflected the mission of the particular variant. The Yak-28 had a top speed of 735 mph and was armed with one or two 30mm cannons and up to 4,410 pounds of bombs and missiles. Following its introduction in 1960, the Yak-28 served the Soviet Union, Russia, Turkmenistan and Ukraine. Nearly 1,800 were produced.

Connecting Flights

If you enjoy these Aviation History posts, please let me know in the comments. And if you missed any of the past articles, you can find them all at Planelopnik History. You can also find more stories about aviation, aviators and airplane oddities at Wingspan.