Welcome to This Date in Aviation History, getting of you caught up on milestones, important historical events and people in aviation from March 23 through March 26.

March 23, 1948 – The first flight of the Douglas F3D Skyknight. Today, modern jet fighters with powerful radars are capable of locating and destroying enemy targets day or night and in all types of weather. But in WWII, radar tracking systems were in their infancy, and specialized night fighters were developed to carry the bulky early radar sets aloft and seek out enemy aircraft. This specialization continued after the war and into the jet age, along with the designations of day fighter and night fighter.

In 1945, the US Navy issued a requirement for a jet-powered, radar-equipped night fighter that would be capable of operating from aircraft carriers. They accepted proposals from Grumman and Douglas, and the Douglas offering was awarded a development contract in April 1946. Unlike Grumman’s proposal, which featured four engines, lead designer Ed Heinemann and the team at Douglas created a twin-engine fighter built around two Westinghouse J34 engines housed in nacelles nestled along the side of the fuselage. Following standard postwar design practices, the Skyknight had straight wings and tail, and the J34 engines gave it a top speed of 565 mph. The F3D was the Navy’s first two-place jet and the pilot and radar operator sat side-by-side in a large cockpit, but they had no ejection seats. In case of emergency, the crew were required to exit through an escape chute and drop out of the bottom of the aircraft, similar to the system that would later be used on the Douglas A-3 Skywarrior. To seek out enemy targets, two radars were housed in the bulbous nose, with one acting as a search radar and the other as a tracking radar. The third radar was located in the tail to alert the crew to attacks from behind during night missions. Once the enemy target was acquired, the Skyknight crew could engage it with four 20mm cannons, rockets, and eventually Sparrow air-to-air missiles.

While the F3D (later redesignated F-10) was never designed to be a dogfighter, it’s handling capabilities were still quite good, and it could could even out turn the Soviet MiG-15. Though designed operations from US carriers, the US Marine Corps operated the upgraded F3D-2 Skyknight from land bases during the Korean War, usually in support of nighttime bombing missions. On November 2, 1952, Marine Corps pilot Maj. William Stratton and radar operator MSGT Hans Hoglind of VMF-513 Flying Nightmares claimed the first ever nighttime radar-led kill of one jet by another when they claimed to have shot down a North Korean Yak-15. Later that month, Skyknight pilots claimed the first victory over a MiG 15 and, in December 1952, a Skyknight crew claimed the first radar lock-on kill of an enemy aircraft without visual contact when USMC pilots downed a North Korean Polikarpov Po-2. Throughout the war, Marine Corps pilots flying the Skyknight were responsible for destroying more enemy aircraft than any other US Navy fighter, while only a single Skyknight was lost in air-to-air comba.

The Skyknight was gradually phased out of service following the Korean War, but it continued to serve as a test platform, most famously during the development of the radar-guided Sparrow missile. The Skyknight was the first aircraft to be fitted with an operational missile of this type. The Skyknight was also the only Korean War-era jet to see service in Vitenam, where it flew as an electronic warfare platform prior to the introduction of the Grumman A-6 Intruder. Marine Corps Skyknight pilots made history again when they carried out the first airborne radar jamming mission in support of a US Air Force raid on missile sites near Hanoi in 1965. While only 265 Skyknights were produced, they hold an outsized place in Naval aviation history, with the last Skyknight serving until 1970.

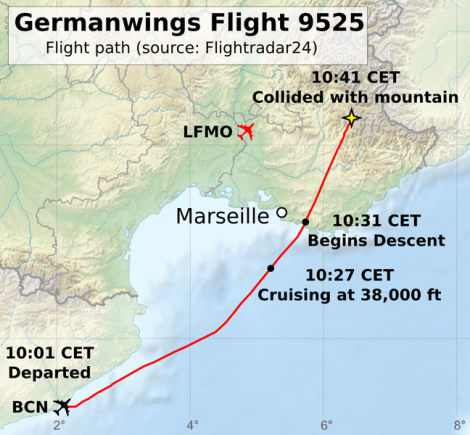

March 24, 2015 – The crash of Germanwings Flight 9525. Commercial airline passengers can usually rest assured that when they board an aircraft the pilot is in no more of a hurry to crash the plane than we as passengers are, and that the pilot in command will do everything in their power to prevent a crash. However, on a number of occasions in commercial aviation history, airline passengers and people on the ground have fallen victim to a deranged pilot who commits what is known as suicide by pilot where, for whatever reason, the pilot chooses to crash the aircraft intentionally and kill all those on board along with him. While the occurrences are certainly rare, suicide by pilot does happen. In recent history, the first officer of EgyptAir Flight 990 allegedly locked the captain out of the cockpit and flew his Boeing 767 into the Atlantic Ocean, killing 217 passengers and crew. And, it’s possible that the captain of Malaysian Airlines Flight MH 370 intentionally flew his Boeing 777 deep into the southern Indian Ocean before running out of fuel and crashing. However, may never know the truth. There can be little doubt about, though, what happened to Germanwings Flight 9525, when investigators believe that first officer Andreas Lubitz deliberately crashed into the French Alps while piloting an Airbus A320 (D-AIPX). There is ample, though circumstantial evidence for suspicion to fall on the Germanwings pilot.

Lubitz became a trainee pilot for Germanwings’ parent company Lufthansa in 2008, but suspended his training voluntarily after being hospitalized for severe depression. In 2013, he reentered the training program, this time in the United States. After a stint as a flight attendant, Lubitz joined Germanwings as a first officer in 2014. On the day of the crash, he was flying with Captain Patrick Sondenheimer, who had flown for Germanwings for 10 years and amassed 6,000 flight hours. Once the aircraft reached its cruising altitude of 38,000 feet on a flight from Barcelona to Düsseldorf, Captain Sondenheimer left the cockpit for a bathroom break. Once the captain was out of the cockpit, Lubitz locked the door and initiated a rapid descent by setting the autopilot for an altitude of 100 feet and pulling the engines back to idle.

When the captain returned from the lavatory, he found the cockpit door locked. Lubitz had also apparently disabled the keypad that allows entry from the cabin. The cockpit voice recorder (CVR) captured the sounds of Captain Sondenheimer first requesting reentry to the cockpit, then sounds of him banging on the door, followed by sounds of him trying to break the door down. The screams of passengers were also heard on the recording. All the while, Lubitz said nothing, and the only sound recorded from his was his slow and steady breathing. He ignored repeated attempts at communication from air traffic controllers, and a French Mirage fighter was scrambled to the scene. After a 10-minute descent, the airliner crashed into the Alps with such force that rescuers found no piece of the airliner larger than an automobile. All 150 passengers and crew were killed, making it the second worst suicide by pilot in history after the alleged EgyptAir crash, and the deadliest air crash in France since 1981.

The subsequent investigation immediately focused on First Officer Lubitz. A search of his apartment found no suicide note, but investigators did discover a letter addressed to Lubitz stating that a doctor had deemed him unfit for work. Though Lubitz had failed to notify Lufthansa of his status, it is also illegal in Germany for a company to access employees’ private medical records, so there was no way Lufthansa could have known of the change in Lubitz’s medical status. Investigators also found that Lubitz was taking prescription drugs, and had been diagnosed with a psychosomatic illness. Perhaps most damning, investigators found search records on Lubitz’s computer for “ways to commit suicide” and for descriptions of the security provisions of aircraft cockpit doors. They also discovered that Lubitz had been treated for suicidal tendencies and had been denied a commercial pilot license in the US. As a result of the crash and investigation, authorities in seven countries instituted a policy requiring that there be at least two crew members in the cockpit at all times, though the requirement was rescinded by the European Aviation Safety Agency in 2017. Canada followed suit, thought the rule remains in effect in the US.

The final report by the Bureau d’Enquêtes et d’Analyses pour la Sécurité de l’Aviation Civile (BEA) can be read here.

March 24, 1935 – The first flight of the Avro Anson. For a island nation such as England, keeping watch on the surrounding seas is a vital part of national security, and a task which became substantially easier with the arrival of the airplane. By the 1930s, the task of maritime patrol and reconnaissance was performed by large flying boats, but those aircraft were expensive to build and operate, and required large crews. In 1933, the British Air Ministry issued a requirement for a smaller and simpler coastal patrol and maritime reconnaissance aircraft, one that could operate from land bases and complement, though not entirely replace, the flying boats.

The de Havilland Aircraft Company responded with their DH.89 Dragon Rapide, a twin-engine biplane airliner that carried six to eight passengers, while Avro offered its Type 652A, a modified version of their Avro 652 airliner. In the ensuing competition, the Avro aircraft was deemed superior, and an initial contract for 174 aircraft was awarded in 1935. The name “Anson” was given to the project in honor of 18th-century British Admiral of the Fleet George Anson. Like many aircraft developed in the years leading up to WWII, the Anson was a low wing cantilever monoplane with the wing constructed mostly of spruce plywood, while the fuselage was a fabric-covered framework of metal tubes. The Anson was powered by a pair of Armstrong Siddeley Cheetah radial engines that provided a top speed of 188 mph with a range of just under 800 miles. The landing gear was retractable, though it required no less than 144 cranks of a handle in the cockpit to pull the wheels up. Therefore, many shorter flights were taken with the landing gear down.

The Anson was originally designed for a crew of three. The pilot was responsible for aiming the fixed, forward-firing .303 caliber machine gun, while the radio operator/gunner manned a single .303 caliber Vickers K machine gun housed in a dorsal turret. A fourth crew member was added after 1938. In addition to the machine guns, up to 360 pounds of bombs could be carried on underwing stations. The Anson entered service with the RAF in March 1936 and, though it was designed for maritime patrol, it really came into its own as a training aircraft, while it’s patrol duties were taken over by the newly-arrived Lockheed Hudson. By the time England entered WWII, the RAF had 824 Ansons, the majority of which were used to train bomber crews in multi-engine aircraft operation before they transitioned to training in large bombers. It was also used to train navigators, radio operators and bombardiers, and a powered turret was added to train defensive gunners in aerial gunnery.

After the war, production of the Anson continued for use as a small civilian airliner and executive aircraft. By the time production finally ended in 1952, just over 11,000 Ansons had been built, with nearly 3,000 of those produced by Federal Aircraft in Canada, production numbers that are second only to the Vickers Wellington bomber in total aircraft built.

March 25, 1955 – The first flight of the Vought F-8 Crusader. When the first dedicated fighter planes went to war in WWI they were armed with machine guns. By WWII, the machine guns were supplemented with or replaced by harder hitting cannons. In the period after the war, when more powerful jet fighters entered service, machine guns gave way to guided missiles and, in some cases, the guns were removed entirely in the belief that missiles alone, fired from long range, would be sufficient armament. However, battle experience in Vietnam showed that the gun was still a vital weapon for close up fighting, even in a modern fighter. But during the transition from guns to missiles, the Vought F-8 Crusader had the distinction of being the last to use guns as its primary weapon, earning it the nickname “The Last of the Gunfighters.”

Development of the Crusader began in 1952 when the Navy announced a requirement for a new supersonic fighter to replace the problematic Vought F7U Cutlass, an innovative fighter that was plagued with difficulties and only served in relatively small numbers. The requirement called for a carrier-based fighter with a top speed of Mach 1.2 at 30,000 feet, a climb rate of 25,000 feet per minute, and a landing speed not to exceed 100 mph. Though the Crusader represented much of the standard design elements of its day, such as a notched leading edge on the wing for greater yaw stability and a solid stabilator tailplane, it was unique in that its wing was mounted high on the fuselage. To reduce landing speeds and improve pilot visibility, the entire wing pivoted upward seven degrees, an innovation that earned Vought and the Navy Bureau of Aeronautics (BuAer) the Collier Trophy in 1956. Despite this innovation, high landing speeds still required the carrier to steam at full speed during landing operations. The F-8

A US Navy F-8D Crusader of Fighter Squadron VF-111 “Sundowners” fires a Zuni rocket over South Vietnam in 1965. (US Navy)The Crusader was powered by a single Pratt & Whitney J57 afterburning turbojet fed through a large intake on the fighter’s chin, and high speed soon became its calling card. On the F-8's maiden flight over the California desert, test pilot John Konrad pushed the Crusader past the sound barrier. It was the first US carrier-based fighter to exceed 1,000 mph, and won the Thompson Trophy for achieving a speed of 1,015 mph. On July 16, 1957, Maj. John Glenn, who would later become the first American to orbit the Earth, made the first non-stop transcontinental flight at an average speed of over Mach 1. Maximum speed in normal operations was Mach 1.7, and cruising speed was 570 mph with a combat radius of 450 miles. Based on experience in the Korean War, where machine guns proved to lack the hitting power to knock down enemy fighters, the Crusader was armed with four 20mm Colt Mk 12 cannons in the lower fuselage capable of firing 1,000 rounds per minute and, on earlier models, a retractable tray was installed below the fuselage that could hold air-to-air or air-to-ground rockets. In later variants, the tray was removed to provide more space for fuel. Hardpoints on the side of the fuselage or under the wing carried rockets, missiles or bombs.

The Crusader entered US Navy service with fighter squadron VF-32 in March 1957, and soon joined the rest of the fleet as a day fighter. Early F-8s were fitted with a small radar in the nose, while later models received more powerful AN/APQ radars which turned the F-8 into a true all-weather fighter. The Crusader made its operational debut during the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962 when RF-8A reconnaissance aircraft flew low-level, high-speed photo missions over the island and provided irrefutable evidence to the world that the Russians were indeed building nuclear missiles bases in Cuba. In Vietnam, Crusaders were the first to engage North Vietnamese fighters, and also took part in ground attack missions. Crusader pilots claimed 19 enemy fighters shot down, all but two being MiG-17s. Vought eventually produced 1,219 Crusaders, and the type was retired from active duty in 1976, though the reconnaissance variant served until 1987. Crusaders also flew for the Philippines and France, with France retiring the last of their Crusaders in 1999.

March 26, 1940 – The first flight of the Curtiss C-46 Commando. Frederick the Great (or perhaps Napoleon) famously said that an army, like a snake, travels on its stomach, and, since the earliest days of warfare, supplying the troops in the field has always been a critical aspect of waging war. Even as late as WWII, the horse and mule still played a vital role in logistics, and continued to do so throughout the conflict. But during the Second World War the airplane finally became a major mover of large amounts of materiel, capable of covering far greater distances than previously imagined, even across the tallest mountains in the world.

The C-46 Commando began its life as a pressurized high-altitude airliner, known as the Curtiss CW-20, that Curtiss hoped would compete with the Douglas DC-4 and Boeing 307 Stratoliner, both four-engine airliners. Unlike its competitors, however, the CW-20 was designed with two engines to keep the design simpler, and was also given a “double bubble” fuselage. Where most aircraft have a single pressurized tube for passengers and cargo, a double bubble design stacks one tube on top of another, giving the aircraft a figure-8 cross section which allows for more internal space. Unfortunately for Curtiss, the airlines’ interest in the CW-20 was tepid at best, and no firm orders were placed for the aircraft. Still, Curtiss had 25 letters of intent to purchase in hand, so they began production of the 24-34 seat airliner anyway. The first prototype was purchased by the US Army Air Forces, but they returned the aircraft to Curtiss, who then sold it to BOAC. However, General Henry “Hap” Arnold saw the CW-20's potential as a cargo aircraft, and he ordered 46 modified CW-20As adapted for cargo with the designation C-46 Commando.

The most obvious difference between the CS-20 and The C-46A was the replacement of the double tail with a single vertical stabilizer. It also had enlarged cargo doors, a strengthened floor, and a cabin that could quickly convert from cargo to passengers. The Army subsequently ordered 200 of these aircraft, and the engines were changed from the original Wright R-2600 Twin Cyclones to a pair of more powerful Pratt & Whitney R-2800 Double Wasp engines. The Commando was introduced in 1941 at the start of WWII, and earned distinction for its service in the China-Burma-India Theater. There, the Commando’s high-altitude design made it the ideal aircraft for flying supplies over the Himalayas, better known as The Hump, and provided vital materiel to the armies of the Republic of China fighting against the Japanese. The C-46 could haul more cargo than other twin-engine cargo aircraft of its day, and loads often included light artillery, fuel, ammunition, aircraft parts, and even livestock. Its powerful engines allowed the Commando to fly in the thin air over the world’s tallest mountains, and loads of up to 40,000 pounds were possible in emergency situations. It could also operate fully loaded on a single engine.

Still, the Commando was not without its faults. Despite is cargo-hauling bona fides, the Commando had a reputation for poor reliability, and many pilots nicknamed the aircraft the “flying coffin” or the “Curtiss Calamity.” It was plagued with problems with its automatic propeller pitch control, engine fires, and unexplained airborne explosions. At least 31 Commandos exploded in flight over the inhospitable Himalaya. Curtiss built nearly 3,200 Commandos during the war, and they hoped to return the C-36 to civilian airliner service once the war had ended. But high maintenance costs and poor fuel economy meant that the airlines simply weren’t interested. So the C-46 went back to what it did best, hauling cargo, and many still ply the harsh northern and arctic routes to this day.

Short Takeoff

March 23, 1998 – The first flight of the Chengdu J-10, a lightweight, all-weather, multirole fighter developed and produced by China’s Chengdu Aircraft Industry Group. The fighter features a delta wing and forward canard and bears a strong resemblance to the Eurofighter Typhoon, though it is powered by only a singe engine. With fly-by-wire controls, the J-10, NATO reporting name Firebird, is comparable in performance capability to the General Dynamics F-16 Fighting Falcon and the Dassault Rafale. Pakistan is the sole international customer for the J-10, though Iran has expressed an interest in the fighter as well. Approximately 400 J-10s have been produced to date.

March 23, 1994 – Following a midair collision, aircraft debris crashes into soldiers assembled on the ground in what is known as the Green Ramp disaster. While practicing a flame-out landing at Pope Air Force Base in North Carolina, a US Air Force F-16D Fighting Falcon collided with the tail of a C-130 Hercules landing ahead of it on the same runway. The F-16 crew ejected, but the wreckage of the fighter struck the ground and erupted in a huge fireball. The flaming wreckage struck a C-141 Starlifter waiting on the tarmac, then careened into a group of soldiers of the 82nd Airborne from adjacent Ft. Bragg assembled in a part of the base called the Green Ramp. Twenty-three soldiers were killed immediately, 80 were injured, some severely, and a twenty-fourth soldier died nine months later. The disaster is the largest single loss of life suffered by the 82nd since WWII. The C-130 landed safely, and the crew of the F-16D was unhurt. An investigation placed the majority of the blame for the midair collision on civilian and military controllers at Pope Air Force Base and, while some blame was placed on the F-16 crew, the pilot was not disciplined.

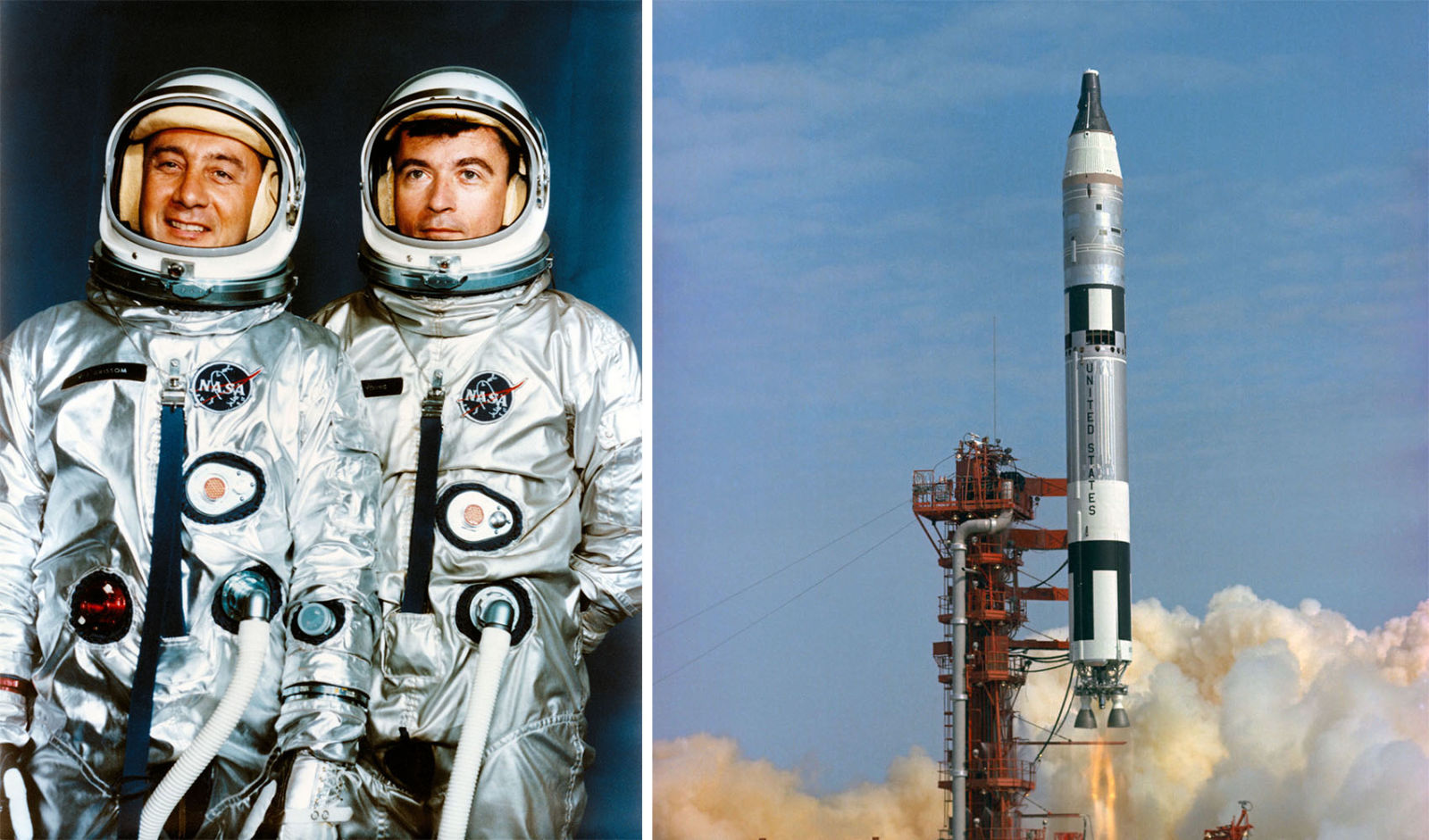

March 23, 1965 – The launch of Gemini 3. Gemini 3 was the third launch of Project Gemini, and the first to carry astronauts into space. The two-man crew of Virgil “Gus” Grissom and John Young made three orbits of the Earth and reached an altitude of 139.3 miles at apogee. The mission was designed to test the maneuverability of the new Gemini spacecraft, and the crew used onboard thrusters to alter the craft’s altitude during flight for the first time. On splashdown, an error in wind tunnel testing caused the capsule to miss its landing point by 45 miles, and the astronauts had to wait 30 minutes for pickup. Grissom died in 1967 in a launchpad fire during a test of Apollo 1, but Young went on to a long career with NASA, and served as the commander of the first two flights of the Space Shuttle.

March 24, 1971 – Boeing cancels the B2707 supersonic transport. Envisioned as a larger and faster supersonic transport to rival theAérospatiale/BAC Concorde, the B2707 arose from a competition initiated by the National Supersonic Transport program announced by President Kennedy in 1963. The B2707 project advanced as far as the construction of two prototypes, neither of which were completed, before the project was canceled. Rising environmental concerns over pollution, fuel consumption, and noise levels, as well as a lack of funding, ultimately led to the demise of the program and the loss of as many as 60,000 jobs.

March 24, 1944 – RAF Flight Sergeant Nicholas Alkemade jumps out of his burning bomber without a parachute during a raid on Germany. Alkemade was taking part in a raid on Berlin when his Avro Lancaster was attacked and shot down by a Junkers Ju 88 night fighter. With the bomber on fire and his parachute damaged, Alkemade decided it would be preferable to die from falling rather than being burned to death. So he bailed out at 18,000 feet and fell into a forest, where tree branches slowed his fall before he came to rest in a deep snowdrift. Despite the fall, Alkemede suffered only severe bruising and a sprained leg. He was captured by German troops and finished the war as a POW. Alkemade died in 1987.

March 24, 1939 – The death of Richard Halliburton. The 1930s was a wild era of barnstorming, exploration and daredevilry, and one of the more famous daredevils was Richard Halliburton. Born on January 9, 1900 in Brownsville, Texas, Halliburton initially found fame after swimming the length of the Panama Canal while paying a toll of just 39 cents, and was the first to climb Mt. Fuji in winter. His contribution to aviation history stems from an epic, round-the-world flight in a modified Stearman C3-B named Flying Carpet with pilot Moye Stephens (eventual co-founder of Northrop Aviation) at the controls. Halliburton called it “one of the most fantastic, extended air journeys ever recorded,” taking 18 months and covering 33,660 miles while visiting 34 countries. Halliburton died (presumed) in 1939 while attempting to cross the Pacific Ocean from Hong Kong to San Francisco in a Chinese junk.

March 25, 1971 – The first flight of the Ilyushin Il-76. The strategic airlifter was first developed by Ilyushin as a commercial freighter in 1967 to replace the turboprop-powered Antonov An-12, and it also saw service with the Russian military as a cargo aircraft, transport and aerial tanker. Like most Russian aircraft, the Il-76 was built to operate from unimproved or grass runways, a capability that has proven especially useful in international disaster relief. The Il-76, NATO reporting name Candid, has been developed into numerous variants and has been exported to 37 international customers. The aircraft remains in production, and 960 have been built to date.

March 25, 1958 – The first flight of the Avro Canada CF-105 Arrow, an attempt by the Canadian aviation industry to develop and produce an indigenous supersonic interceptor. The project progressed as far as five flying prototypes which displayed excellent performance and handling, and test flights reached a top speed of Mach 1.98. However, in a decision that remains controversial to this day, the Canadian government canceled the project, citing concerns of cost overruns, the emergence of intercontinental ballistic missiles, and the threat of Soviet espionage. Following the cancelation on February 20, 1959, all the finished and unfinished aircraft were destroyed along with all engineering tools and plans.

March 25, 1931 – The first flight of the Hawker Fury, a development of the earlier Hawker F.20/27 and the first RAF fighter capable of speeds in excess of 200 mph. The Fury improved on the F.20 primarily with the introduction of the Rolls-Royce Kestrel V-12 engine that was in use in the Hawker Hart light bomber. The Fury I entered service with the RAF in 1931, with the upgraded Fury II joining five years later. It remained in service until January 1939, shortly before England’s entry in to WWII. A total of 275 Furies were produced.

March 25, 1928 – The birth of James “Jim” Arthur Lovell, an American astronaut who took part in the Gemini and Apollo space programs and is best known as the commander of the ill-fated Apollo 13 mission. Prior to his NASA career, Lovell flew the McDonnell F2H Banshee for the US Navy before entering test pilot school and then applying for the Astronaut Corps. His first flight to space was on Gemini 7, where Lovell, along with Command Pilot Frank Borman, set an endurance record of 14 days in space. Later, Lovell commanded Gemini 12 with pilot Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin, and also served as the command module pilot of Apollo 8, the first Apollo mission to orbit the Moon. Following the unsuccessful Apollo 13 mission, Lovell left NASA to work in private industry.

March 26, 1956 – The first flight of the Temco TT Pinto, a two-seat, tandem jet trainer developed by Temco Aircraft for the US Air Force. The Pinto was developed in response to an Air Force requirement for a primary jet trainer, but lost the competition for a production contract to the Cessna T-47 Tweet. The Pinto was powered by a single Continental Motors J69 jet engine and had a maximum speed of 345 mph, though it proved to be underpowered, particularly for emergency maneuvering. Fifteen were built, but they were retired by the end of 1960 and sold as surplus. Seven remain registered to civilian pilots, while one resides in the Philippine Air Force Museum.

Connecting Flights

If you enjoy these Aviation History posts, please let me know in the comments. And if you missed any of the past articles, you can find them all at Planelopnik History. You can also find more stories about aviation, aviators and airplane oddities at Wingspan.