Welcome to This Date in Aviation History, getting of you caught up on milestones, important historical events and people in aviation from April 6 through April 9.

April 6, 1938 – The first flight of the Bell P-39 Airacobra. At the beginning of WWII, the Bell P-39 Airacobra was the principal fighter aircraft in US Army Air Corps service. But the Airacobra often gets criticized as ineffective when with compared with later fighters such as the North American P-51 Mustang and Republic P-47 Thunderbolt. The Airacobra’s lack of a turbo-surpercharger certainly rendered it ineffective as a high altitude interceptor or fighter, but despite the criticism, the Airacobra was still a very effective warplane, and proved its mettle against ground targets and low-flying bombers, particularly in the hands of Soviet pilots.

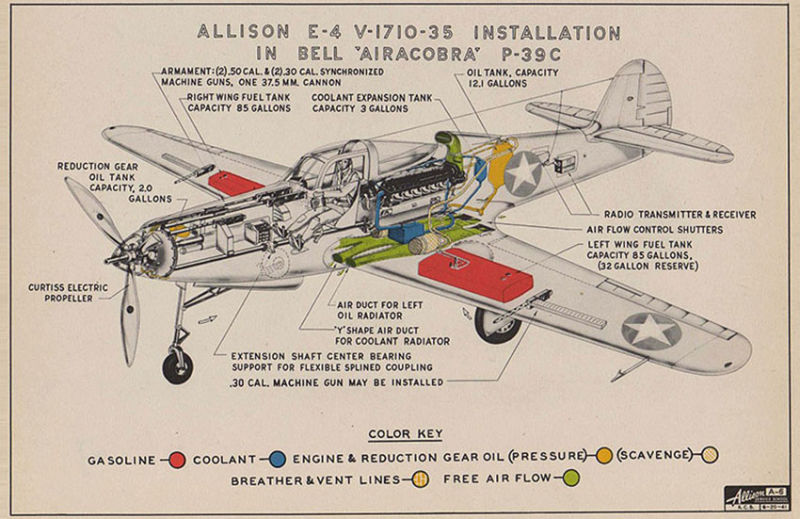

In 1937, the USAAC issued the most ambitious requirements to date for a new fighter. They called for 1,000 pounds of heavy armament including a cannon, a tricycle landing gear, a level airspeed of at least 360 mph and the ability to reach 20,000 ft in less than six minutes. The requirements also called for a turbo-supercharged Allison engine for high-altitude performance. With all the weaponry the Army requested, particularly the large cannon, Bell had to find a way to fit it all inside the airframe. So they decided on the innovative solution of placing the engine behind the pilot, with a drive shaft that passed under the cockpit and turned the propeller through a gear system. The placement of the engine helped with the fighter’s center of gravity and, though some pilots voiced concerns about the drive shaft running underneath the seat, the system proved safe and reliable.

With the engine placed behind the pilot, the nose of the Airacobra was empty. So Bell filled it with 37mm M4 cannon, a weapon specifically designed for the Airacobra and manufactured by Oldsmobile. Because of its heavy recoil, the cannon had to be placed on the aircraft’s centerline, and it fired through the center of the propeller spinner, an arrangement that was made possible by by the geared propeller and drive shaft below the center of the propeller hub. In addition to the cannon, the Airacobra was armed with two .50 caliber machine guns in each wing and two more in the nose firing through the propeller.

When testing of the XP-39 prototypes commenced, initial speed results were disappointing. The Army ordered that the aircraft be evaluated in a National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) wind tunnel to see if the fuselage shape could be made more streamlined to increase speed, and it was here that the history of the Airacobra took a significant turn. The turbo-supercharger for the Allison V-1710 V-12 engine was cooled by a scoop on the left side of the aircraft, and NACA said the ducting had to be redesigned to eliminate the scoop to reduce drag. However, there was simply no place to move the scoop in the tightly packaged fuselage. So Larry Bell made the controversial decision to continue development of the P-39 with the turbo-supercharger removed, instead using only a single-stage supercharger. While speeds did increase with the improved aerodynamics, the lack of the turbo-supercharger effectively limited the Airacobra to service below 12,000 feet, rendering it ineffective as an interceptor or high-altitude fighter. And, once armor plating was added, the weight increase put a further drag on the Airacobra’s performance.

Nevertheless, the P-39 was sent to the Pacific following the outbreak of WWII, where it proved to be a potent weapon against enemy ground targets and shipping. The Airacobra also saw service in the Mediterranean, notably with the Tuskegee Airmen of the 99th Pursuit Squadron. The British found the Airacobra almost wholly unsuited to their needs, and only outfitted a single squadron with the type. The rest they sent to Russia. And it was in Russia where the P-39 found its greatest success. The Russians appreciated the heavy firepower provided by the cannon and machine guns, as well as the Airacobra’s rugged construction. They particularly liked the Airacobra’s reliable radio. Nearly half of the 9,588 P-39s built were shipped to Russia, where Soviet pilots used the Airacobra primarily in the air-to-air role. Its heavy armament was particularly lethal against German bombers, but it could also hold its own against German fighters at lower altitudes. Russian pilot Alexander Pokryshkin scored 47 of his 59 victories in an Airacobra, making him the highest scoring P-39 pilot of the war. The Airacobra was continuously developed throughout WWII into a myriad of variants, including an attempt at a navalized version called the XFL Airabonita, and the larger, more powerful P-63 King Cobra, which was adopted by the Soviet Air Force.

April 9, 1967 – The first flight of the Boeing 737. At the start of the commercial jet era, the emphasis was on big airplanes. The four-engine de Havilland Comet was the world’s first jet airliner but, when that aircraft began suffering from an alarming string of fatal crashes, Boeing was poised to step in with its own four-engine airliner, the 707. The 707 went on to become one of the most successful airliners of the era and an icon of the early jet age. But a new trend began to develop in the airline industry, one that called for smaller airliners to operate on shorter routes. Boeing followed the 707 with the 727 tri-jet, but airlines still wanted something smaller that would complement Boeing’s other offerings.

Development of the 737 began in 1964 with plans to create an airliner that would accommodate 50-60 passengers. The German carrier Lufthansa signed on as the launch customer a year later, and requested that Boeing increase the seating capacity to 100 passengers. When United Airlines signed on to the project, they wanted an airliner with still more capacity. So the 737 was lengthened again, with the Lufthansa version becoming the 737-100 and the United version becoming the 737-200. However, Boeing found themselves lagging behind competing airliners such as the Douglas DC-9, Fokker F28 Fellowship and British Aircraft Corporation BAC One-Eleven, all of which had advanced to the point of flight certification testing.

To speed the development process, Boeing based the fuselage of their new airliner largely on the 727, using 60% of the 727's fuselage shape, particularly the upper lobe. This gave the 737 the same cross section as its predecessor and allowed for the use of the same cargo pallets as the earlier airliner. Bringing in the 727 fuselage also meant the adoption of 6-across seating in coach, which gave the 737 a distinct advantage over its rival Douglas and the 5-across seating in their DC-9. The relatively short fuselage, when mated to its swept wings, resulted in an aircraft that was just about as long as it was wide, and the 737 was dubbed the “square airplane.” Boeing also eliminated the flight engineer position, helping to set a new industry standard for only two crew members in the cockpit. The company also purposely made the airliner as close to the ground as possible to facilitate ground servicing, and even included an optional air star in the rear of the airliner. The first 737 was constructed at Boeing’s Plant 2 in Seattle, and was the last new airliner to be produced in the same building where the B-17 Flying Fortress, B-47 Stratojet and B-52 Stratofortress had been built. Despite the building’s size, the tail of the first 737 couldn’t be attached inside, so it was fitted outdoors using a crane before the airliner was rolled to the production facility known as the Thompson Site.

Though the 737 has since become the best selling airliner in history, its early days were less rosy. By 1970, Boeing had received orders for only 37 aircraft, and they were considering shutting down production and selling the 737 design to Japanese aircraft manufacturers. But, with the cancellation of the Boeing 2707 supersonic transport (along with the loss of 50,000 jobs), reduction in the production of the 747, and an order for the T-43 version of the 737 from the Air Force, Boeing was able to keep production going. They were also able to continue development of the 737 into a wider range of variants, including the convertible 737C model with accommodations for palletized freight, and the 737QC (Quick Change) variant that featured palletized seating and allowed for a rapid switch from cargo to passenger configurations.

One of the secrets of the 737s success has been the airliner’s ability to continually adapt to changing times in a volatile airliner industry. Following the production of the 737-100 and -200, the last of which was delivered in 1988, Boeing began developing the -300/-400/-500 series, which would later be known as the 737 Classic, each offering improvements in range, economy and passenger capacity. Most importantly, the Classic moved the 737 into the age of modern high-bypass turbofan engines, leaving behind the cigar-shaped Pratt & Whitney JT8D low-bypass turbofans in favor of the CFM International CFM56.

In the early 1990s, Boeing undertook further development of the 737 to compete with rival Airbus and followed the Classic with the 737 Next Generation, which encompasses models -600/-700/-800/-900ER. While much of the 737NG is essentially new, it retains enough commonality with earlier aircraft to make it attractive to airlines with older fleets of 737s. Faced with even stiffer competition from Airbus, development of the venerable 737 airframe continued into the 21st century with the arrival of the 737 MAX beginning in 2011. The MAX 7, MAX 8 and MAX 9 are basically re-engined -700, -800, and -900 airliners with a few additional aerodynamic tweaks such as a tail cone borrowed from the 787 and new split scimitar winglets. The MAX 9 seating a maximum of 220 passengers, a load that exceeds even the highest capacity of the 707. the MAX features still more efficient CFM International LEAP-1B engines for greater range and fuel economy. Deliveries of the MAX began in 2017, and Boeing has orders on the book for more than 4,300 aircraft, though two crashes late in 2018 and early 2019 have raised doubts about the safety of Boeing’s latest iteration of the 737, and the airliner’s future depends on updated software and other safety changes.

In July 2012, the 737 earned the distinction of being the first airliner to surpass 10,000 orders, and nearly 9,000 have been delivered so far. Today, two 737s are landing or departing every five seconds somewhere in the world. As for the prototype, it never entered commercial service, though it did operate as a flying laboratory for NASA for 20 years, and is now on display at the Museum of Flight in Seattle, Washington.

Short Takeoff

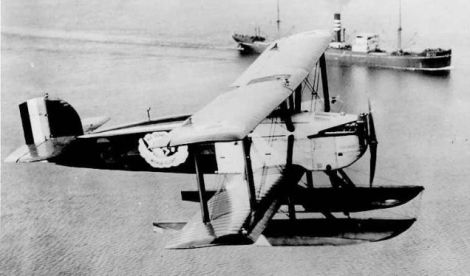

April 6, 1924 – The start of the first successful flight around the world. In 1923, the US Army Air Service requested that Douglas Aircraft Company develop an aircraft specifically for completing a circumnavigation of the globe. Douglas modified five Douglas DT torpedo bombers, and four of them departed from Sand Point, Washington flying westward. Owing to crashes along the way, only two aircraft completed the journey, which covered 27,553 miles and took 175 days to complete, landing back in Seattle on September 28 after making 58 stops along the way. The success of the flight helped establish Douglas as a major aircraft manufacturer.

April 7, 2006 – The first free flight of the Boeing X-37. Also known as the Orbital Test Vehicle (OTV), the X-37 is an unmanned, reusable spacecraft that is a 120% scale derivative of the Boeing X-40. Similar to the much larger Space Shuttle, the X-37 is boosted into orbit by a launch vehicle, then returns to Earth and lands as an unpowered glider. The X-37 is operated by the US Air Force and has completed five orbital missions carrying a classified payload. The fourth mission orbited the Earth for nearly 718 days, and the fifth mission was sent to the the X-37's highest orbit yet to carry out tests and deeply satellites. A sixth mission is slated for 2019.

April 7, 2001 – The launch of 2001 Mars Odyssey, a robotic spacecraft launched into orbit around Mars to gather data about the Martian surface. The spacecraft mapped hydrogen distribution that led to the discovery of vast amounts of ice under the surface of the planet’s polar regions, and also took readings on the amount of radiation on the surface of the planet to help determine any risks associated with a manned landing. The orbiting spacecraft also served as a communications relay for the Spirit and Opportunity rovers on the Martian surface, and handled 95% of all data transmitted to Earth from the rovers. Imagery from Mars Odyssey will also help determine suitable landing sites for future missions.

April 7, 1994 – The attempted hijacking of Federal Express Flight 705. Disgruntled Federal Express pilot Auburn Calloway boarded the cargo flight as a deadheading pilot, carrying a guitar case filled with hammers and a spear gun. He planned to kill the pilots with the hammers (using the spear gun as a last resort), then crash the McDonnell Douglas DC-10-30F (N306FE) so his family could collect a $2.5 million life insurance policy. He chose the hammers to make the crew’s injuries appear consistent with a crash. Though the pilots were seriously injured in the attack, they managed to subdue Calloway and land safely. Calloway claimed insanity, but was convicted and sentenced to two consecutive life terms.

April 7, 1967 – The first flight of the Aérospatiale Gazelle. Designed for light transport, scouting, and light attack duties, the Gazelle was the first helicopter to employ the fenestron enclosed tail rotor configuration which reduces tip vortex loss, protects the tail rotor, and also protects ground crews from the spinning rotor. The Gazelle entered service in 1973, and currently serves the air forces of 20 nations and has seen combat in Lebanon, Rwanda and the First Gulf War. More than 1,700 Gazelles were produced between 1967-1996, and it remains in service today.

April 7, 1922 – The first mid-air collision between two airliners. One of the aircraft, a de Havilland DH.18A (G-EAWO), was flying mail from Croydon in England to Le Bourget in France. On board were the pilot and a young steward. The second aircraft, a Farman F.60 Goliath (F-GEAD), was flying in the opposite direction with a pilot, mechanic, and three passengers. With low clouds and drizzle, the pilots were flying just below the clouds and following a road, but the British pilot was keeping the road to his right, while the French pilot was keeping the road to his left, putting them on a head-on collision course. The aircraft collided 60 miles north of Paris, killing all seven occupants. As a result, rules were adopted to agree on a right-side offset when following roads, and official air lanes were adopted for heavily travelled routes.

April 8, 1944 – The first flight of the Douglas BTD Destroyer. The Destroyer was designed in response to a 1941 US Navy request for a single aircraft to replace both the Douglas SBD Dauntless and the Curtiss SB2C Helldiver. Designed by noted Douglas engineer Ed Heinemann, the Destroyer featured a laminar flow wing and, in a first for a carrier aircraft, a tricycle landing gear. When the Navy changed its requirements, Douglas removed the extra crew member and the defensive armament. Still, only 28 were delivered before the war ended and production was canceled.

April 9, 1964 – The first flight of the de Havilland Canada DHC-5 Buffalo, a cargo and transport aircraft developed from the DHC-4 Caribou and designed for extremely short takeoffs from rugged or unimproved airstrips. Unlike its piston-powered predecessor, the Buffalo is powered by a pair of General Electric CT64 turboprop engines. It was originally pursued by the US Army as a replacement for the Caribou before all fixed-wing aircraft were transferred to the US Air Force. However, the Air Force wasn’t interested in adopting it and only 122 were built. The type certificates for all the de Havilland transports were purchased by Viking Air in Canada who plans to restart production of a newer, more powerful version of the Buffalo as the Buffalo NG (Next Generation).

April 9, 1959 – NASA announces the Mercury Seven, the first American astronauts who took part in the manned Project Mercury spaceflights from May 1961 to May 1963. Alan Shepard was the first Mercury astronaut to travel in space in 1961, just one month after Soviet Cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin. He was followed by Gus Grissom, then John Glenn, who was America’s first astronaut to orbit the Earth. They were followed by Scott Carpenter, Wally Schirra, and Gordon Cooper. The seventh member of the group, Deke Slayton, was grounded for health reasons, but served as NASA’s Director of Flight Crew Operations until 1972 and eventually went to space as part of the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project in 1975. The Mercury Seven formed the core of American astronauts, and members of the group played a role in all NASA space missions of the 20th century.

Connecting Flights

If you enjoy these Aviation History posts, please let me know in the comments. And if you missed any of the past articles, you can find them all at Planelopnik History. You can also find more stories about aviation, aviators and airplane oddities at Wingspan.