Welcome to This Date in Aviation History, getting of you caught up on milestones, important historical events and people in aviation from April 13 through April 16.

April 13, 1970 – An oxygen tank explodes in the Apollo 13 Service Module. Triskaidekaphobia is a word that comes to us from the Greek, and it means having an extreme superstition about, or fear of, the number 13. As a matter of tradition, many tall buildings don’t number the 13th floor, counting from 12 to 14, and Friday the 13th has become famous as a day for bad luck and ill omens. As the Apollo program progressed from the ill-fated Apollo 1, the rational scientists at NASA chose not skip the number 13 despite its ominous history, though in hindsight they may have wished that they had.

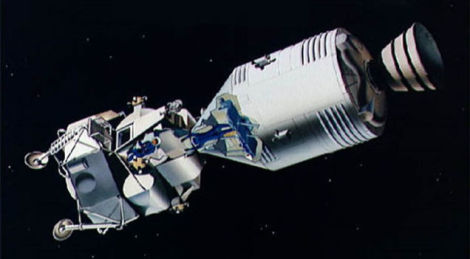

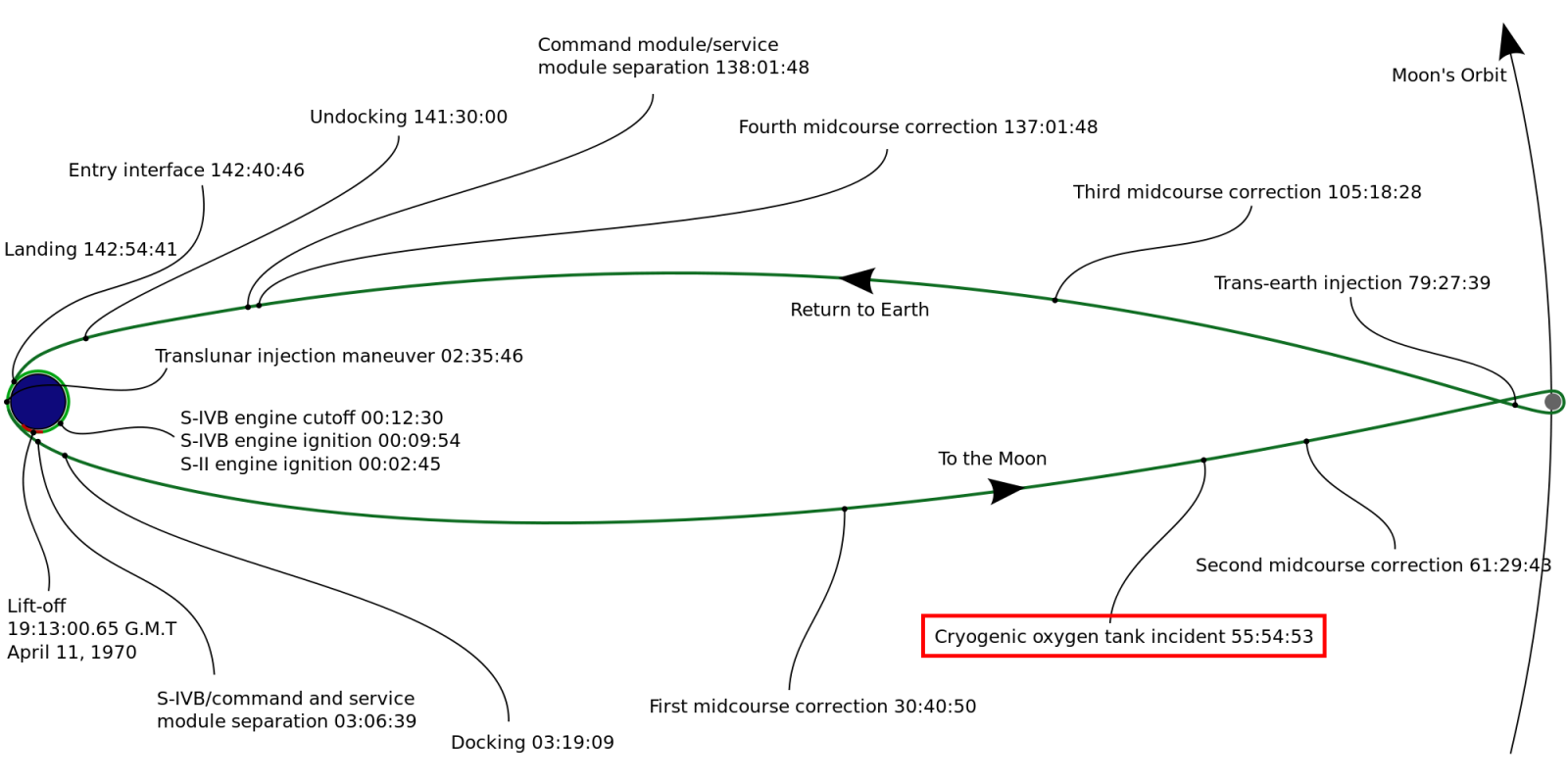

Apollo 13 was the seventh manned mission of the Apollo program and the third mission slated to land on the moon. On board were mission commander James Lovell, Command Module pilot Jack Swigert, and Lunar Module pilot Fred Haise (astronaut Ken Mattingly had originally been slated to serve as Command Module pilot, but fears that he had contracted rubella from his one of children led to his replacement by Swigert). The launch on April 11 took place without any significant problems, and the crew successfully detached the Service Module (SM) and Odyssey Command Module (CM) to perform the transposition maneuver that would attach the Aquarius Lunar Module (LM, pronounced “lem”) to the nose of the CM and allow the astronauts to pass between the CM and the LM. Once the spacecraft reached lunar orbit, the LM, with two astronauts aboard, would then separate and fly to the surface, while the third astronaut remained in orbit in the CM.

The barrel-shaped Service Module, as its name implied, was filled with various tanks and batteries and one of its duties was to supply electricity and oxygen to the CM throughout the mission. On April 13, two days after launch and about three-fourths of the way to the moon, NASA flight controllers instructed Swigert to activate the hydrogen and oxygen tank stirring fans, a routine procedure that kept the tanks functioning properly and ensured proper readings of the tanks’ levels. Two minutes later, the crew heard a loud bang, and Lovell reported the words that have since become synonymous with something going seriously wrong: “Houston, we’ve had a problem.” Looking out the window of the CM, Lovell told Mission Control that the spacecraft was venting “a gas of some sort” into space. Unknown to the crew at the time, one of the oxygen tanks had exploded, taking not only precious oxygen for the crew, but also electricity and water. Soon, the CM had only battery power and limited water, and what little electrical power that remained would be needed for re-entry. So the CM was shut down and the astronauts moved to the LM, which had its own power supply. Without Aquarius to act as a lifeboat, the accident would almost certainly have been fatal.

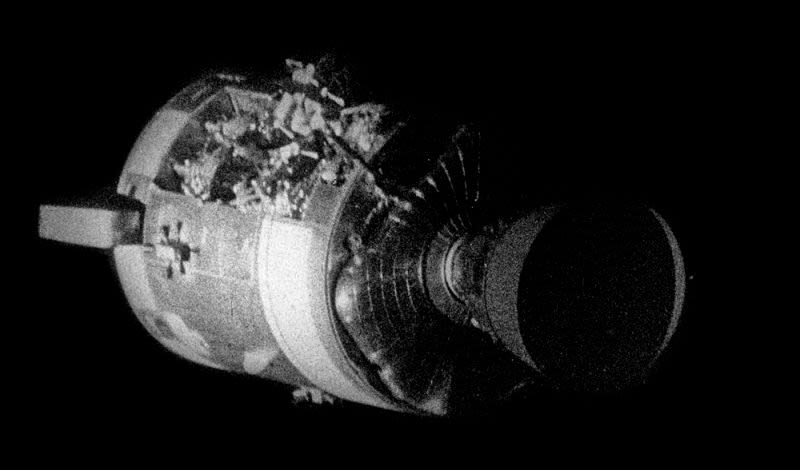

Following the official decision to abort the Moon landing, NASA was now faced with the problem of getting the astronauts home safely, a scenario for which there was no procedure. Rather than turn around and come directly back to Earth, Flight Director Gene Kranz decided it was best to allow the spacecraft to swing around the Moon and use the Moon’s gravity to slingshot the astronauts back to Earth. The astronauts had to use the LM’s landing rocket to make manual course corrections, and the four-and-half-minute burn, something the astronauts had never trained for, was so accurate that only two subsequent small course corrections were needed. Though the LM had plenty of oxygen, the removal of carbon dioxide became critical, and the astronauts had to jury-rig a system using incompatible C02 scrubbers from the CM. They also faced critical shortages of water and food. Once they were close enough to Earth, the astronauts jettisoned the Service Module and could finally get a good look at the damage and saw that an entire side panel of the module had blown off. After photographing the damaged module, they returned to the CM and jettisoned Aquarius. Despite concerns about the possibility of a damaged heat shield, Odyssey splashed down safely in the Pacific Ocean on April 17.

An analysis of the explosion determined that damaged insulation on the stirring fan caused a short-circuit and fire that ignited the tank explosion. Even though the mission to land on the Moon wasn’t successful, the unintended orbital trajectory around the Moon gave the Apollo 13 astronauts the record for the absolute distance flown from the Earth by a manned spacecraft. Apollo 13 was the last spaceflight for Commander Lovell, the only man to fly to the Moon twice without landing on its surface. Jack Swigert was slated to return to space as part of the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project in 1972, but was removed from the flight for his role in a postage stamp scandal surrounding Apollo 15. Fred Haise also never returned to space, though he did take part in the early Space Shuttle program, piloting the Enterprise to three landings as part of the Shuttle Approach and Landing Tests.

April 15, 1952 – The first flight of the Boeing B-52 Stratofortress. By the end of WWII, Boeing had earned a solid reputation for making large bombers with the rugged B-17 Flying Fortress and the state-of-the-art B-29 Superfortress. But with the coming of both the jet age and the nuclear age, the Air Force needed a new bomber with extreme range that could fly deep into enemy territory to deliver nuclear weapons. Initially, Boeing proposed the Model 462 in 1946, a straight-wing bomber that would be powered by six turboprop engines. Essentially, it would be a scaled-up version of a WWII bomber, with at least five defensive turrets and accommodations for two crews that could rotate during long-range missions. But over the next year of development, the Air Force kept changing the requirements, and Boeing kept changing the design. By the end of 1947, the program was on the verge of cancelation.

Though the turbojet engine was clearly the powerplant of the future, the Air Force wasn’t so sure, and wanted to hedge its bets by sticking with turboprops. After all, range was a primary concern, and early jet engines were notoriously thirsty. Boeing proposed yet another turboprop design in October 1948 and, when the Air Force wasn’t impressed with its capabilities, a team of Boeing engineers working in a hotel room in Dayton, Ohio came up with the preliminary design of an eight-engine turbojet bomber based on the B-47 Stratojet and its 35-degree swept wing. Similar to the B-47, the engines on the Stratofortress would be housed in pods under the wings, and the landing gear would be centered on the fuselage with outriggers on the wings. To handle crosswind landings, Boeing came up with the innovative solution of having the main landing wheels pivot up to 20-degrees to stay aligned with the runway centerline. Like the B-47, the two pilots would be seated in a tandem configuration under a greenhouse canopy, but Air Force General Curtis LeMay, a veteran of WWII bombing campaigns, insisted that the pilots be seated side by side.

Only three copies of the initial B-52A model were built, and the first production model, the B-52B, entered service with the Air Force on June 29, 1955. This aircraft featured improved avionics and engines that could achieve an extra 12,000 pounds of thrust by using water injection. As a product of the Cold War, the B-52's primary mission was to deliver nuclear weapons, and though it was never called on to carry out that mission, it still served as a powerful deterrent to Soviet aims around the world. When the advent of the surface to air missile jeopardized the B-52's high altitude mission, the bomber showed its tremendous flexibility by adapting to low level penetration missions. And, in a further testament to its flexibility, the bomber that was originally designed solely to drop nuclear munitions became one of the most powerful weapons of conventional warfare when it went into battle in Vietnam. Beginning with Operation Rolling Thunder in 1965, and following modifications to carry still more bombs, B-52 crews flew a total of 124,532 sorties throughout the war. A typical bomb load for the B-52 in Vietnam was 54,000 pounds of conventional bombs, or about the same load as ten B-17s.

Following Vietnam, many of the older B-52s were retired due to their age, though newer G and H models were kept active for nuclear standby missions. Many were relegated to the Arizona desert, then destroyed as part of arms limitation treaties with the Soviet Union. When America went to war in the Persian Gulf, B-52s took part in Operation Desert Storm, flying from bases in England, Spain, Saudi Arabia and as far away as Louisiana to attack targets in Iraq. Despite efforts to replace the B-52, first with the Rockwell B-1 Lancer, the Buff soldiers on, providing capabilities in firepower and mission flexibility that simply can’t be matched by newer designs. When the Lancer is replaced by the proposed B-21 Long Range Strike Bomber, the B-52 will still be flying. In fact, the Air Force currently plans to keep the B-52 in service until 2045, an astonishing 90 years after it first entered service, and plans are currently underway to replace the eight Pratt & Whitney TF33 low-bypass turbofans with eight similarly sized regional jet engines.

April 15, 1935 – The first flight of the Douglas TBD Devastator. The 1930s was an extraordinary decade for aircraft development. The fabric-covered metal and wooden frames of the biplane era were left behind in favor of the all-metal cantilevered monoplane, and each new aircraft brought further innovations in construction, capability, speed, or range. But with the outbreak of WWII in 1939, aircraft development revved into high gear, and aircraft that were innovative and groundbreaking when they rolled out were quickly rendered obsolete. Such was the fate of the Douglas TBD Devastator.

In 1934, the US Navy was seeking a new dive bomber to operate from its carriers, and the Devastator entered into competition for a Navy contract against the Brewster SBA, the Vought SB2U Vindicator, and the Northrop BT-1 (which would later evolve into the Douglas SBD Dauntless). The Devastator, which eventually won the competition, provided many firsts for the Navy. It was the first monoplane to enter carrier service, it was the Navy’s first all-metal aircraft, and the first with a fully enclosed cockpit. It was also the first to have hydraulically powered folding wings. The semi-retractable landing gear allowed the wheels to protrude from under the wings and protect the airframe in the event of a wheels-up landing. The Devastator could carry up to 1,200 pounds of bombs or a single torpedo, had a single forward-firing .30 or .50 caliber machine gun, and a rear-firing .30 caliber machine gun for defense against enemy fighters. Power came from a single Pratt & Whitney R-1830 Twin Wasp radial that gave the Devastator a maximum speed of 206 mph, which was relatively fast for its day. However, despite all of these innovations, by the time of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, just six years after the Devastator’s first flight, it was already almost completely obsolete.

Nevertheless, Devastator pilots fought well in the opening stages of the war in the Pacific, effectively attacking ground and shipping targets while flying from the carriers USS Enterprise (CV 6), USS Yorktown (CV 5) and USS Lexington (CV 2). But the pivotal Battle of Midway on June 3-7, 1942 showed that the Devastator’s time had completely passed. In the opening stages of the battle, 41 Devastators, nearly all the TBDs in operation at the time, were dispatched against the Japanese fleet from USS Hornet (CV 8), Enterprise and Yorktown. Due in large part to its lack of maneuverability and slow speeds, the Devastator proved to be a sitting duck for Japanese guns. On torpedo runs, the TBDs had to maintain a mere 115 mph in order to drop their torpedoes, which made them easy prey for Japanese A6M Zero fighters and antiaircraft gunners. Of the 41 aircraft that took off, only six returned from the mission, and they had scored no hits on the Japanese carriers. Part of this was due to malfunctioning Mark 13 torpedoes, but clearly, the Devastator’s days as an effective torpedo bomber were over. However, the loss of the Devastators and their crews was not entirely in vain, as the attacks left the Japanese carriers vulnerable for the follow-up attacks by Dauntless dive bombers which ultimately resulted in a lopsided victory for the US Navy and heralded a titanic shift in the balance of power in the Pacific.

After Midway, the Navy immediately removed the TBD from frontline service, and the remaining aircraft were relegated to flight training duties or served as training pieces for mechanics and firefighters. The final Devastator was scrapped in 1944, and none of the 130 production aircraft remain today. Though the Devastator’s replacement, the Grumman TBF Avenger, fared little better at first, shifting tactics and the gradual achievement of air superiority in the Pacific finally allowed the torpedo bomber to become an effective weapon later in the war.

Short Takeoff

April 13, 2019 – The first flight of the Scaled Composites Stratolaunch, a dual-fuselage heavy-lift mothership designed as a completely reusable first stage to launch payloads into space. Envisioned by the late Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen, the aircraft, nicknamed Roc after the mythical bird that could carry an elephant, takes the title of world’s largest aircraft away from the Hughes H-4 Hercules (popularly known as the Spruce Goose) with a wingspan of 385 feet and a length of 238 feet. The three-person crew flies from the right fuselage cockpit, and the other fuselage remains empty and unpressurized. The Roc is powered by six Pratt & Whitney PW4056 turbofans and is designed to carry a payload of 550,000 pounds and has a maximum takeoff weight of 1.3 million pounds. When operational, it is planned that Stratolaunch will fly to an altitude of 35,000 feet to release a Pegasus XL rocket or the rocket-powered Dream Chaser Cargo System spaceplane, and the company hopes to launch three rockets by 2022.

April 13, 1996– The death of Charles “Chief” Anderson, a pioneering African American aviator who is known as the “Father of Black Aviation.” Anderson was born on February 9, 1907 in Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania and, by age 20, he decided he wanted to fly. However, nobody would teach him because of his race. Undaunted, Anderson saved and borrowed enough money to purchase a Velie Monocoupe and taught himself to fly it, eventually earning his pilot license in 1929. Anderson found similar obstacles while trying to obtain an air transport license, but help came from Ernest Buehl, a visiting German aviator, who taught Anderson and helped him earn the license in 1932. In 1940, Anderson was recruited by the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama as Chief Civilian Flight Instructor and, in 1941, he was selected by the US Army as Ground Commander and Chief Instructor of Tuskegee’s aviation cadets for the 99th Pursuit Squadron, which became America’s first all-black fighter squadron and part of the Tuskegee Airmen. After the war, Anderson continued training both black and white pilots, operated an aircraft maintenance and sales facility, and founded Negro Airmen International, America’s first African-American pilot’s association.

April 13, 1990 – The first flight of the Sukhoi Su-34, an all-weather strike fighter based on the Sukhoi Su-27 and intended as a replacement for the Sukhoi Su-24. The Su-34, NATO reporting name Fullback, is primarily used against ground and naval targets and also carries out reconnaissance missions. The Su-34's roomy cockpit allows the pilots to move around during long missions, and includes a small galley and rudimentary toilet. It is armed with a single 30mm cannon along with 12 external hardpoints capable of carrying up to 26,500 pounds of rockets, missiles and bombs. The Su-34 entered service in early 2014, and has recently seen action in Syria during Russian intervention in the Syrian Civil War.

April 13, 1945 – Boeing delivers the final B-17 Flying Fortress. Designed in the 1930s as a four-engine heavy bomber for the United States Army Air Corps, the B-17, nicknamed “Flying Fortress” for its bristling defensive armament, was one of the most effective weapons of WWII, particularly in Europe, where it dropped 640,000 tons of ordnance on Germany and its territories, more than any other bomber. Production began in 1936 and continued almost until the end of the war in 1945, with a total of 12,731 aircraft built, two-thirds of which were the B-17G variant. Though the Flying Fortress was quickly retired by the USAAC after the war, it continued in service with other countries, flying for the Brazilian Air Force until 1968. Approximately fifteen B-17s remain flying today.

April 13, 1931 – The first flight of the Boeing YB-9, an experimental bomber funded by the Boeing Company as a development of their Model 200 Monomail mail plane. At a time when many US Army Air Corps bombers were still constructed of wood and canvas, the YB-9 was the first all-metal, stressed-skin, cantilever monoplane bomber built for the USAAC. The YB-9 was powered by two Pratt & Whitney R-1860 radial engines and had a top speed of 188 mph, equal to many contemporary fighter planes. Five YB-9s were built and entered service in September 1932, but they were phased out in just three years. Ultimately, Boeing lost out to the the Glenn L. Martin Company, which offered the much more modern Martin B-10 which entered service in 1934.

April 13, 1928 – The first non-stop flight across the Atlantic from east to west. Just one year after Charles Lindbergh’s famous west-to-east flight from New York to Paris, German aviators Hermann Köhl, Baron Gunther von Hunefeld, and Irishman James Fitzmaurice took off from Baldonnel, Ireland on April 12 in a Junkers W 33 named Bremen. The team flew westward, against the prevailing winds, and planned to land in New York. However, strong winds forced them well north of their intended course, and they landed instead at Greenly Island, Canada after a flight of 37 hours. Their W.33 has been restored and is currently displayed at the airport in Bremen, Germany.

April 13, 1910 – The first flight of the Vickers Vimy Commercial. The Vickers Vimy was a biplane heavy bomber developed for the RAF late in WWII, and while the war ended before the Vimy could see action, the aircraft continued to be the RAF’s main bomber throughout the 1920s and was converted into both an air ambulance and, with an enlarged fuselage, an airliner known as the Vimy Commercial, one of the world’s first purpose-built large airliners. The prototype Vimy Commercial took part in a race to Cape Town, South Africa in 1920, but crashed before completing the race. China, who also operated the bomber version of the Vimy, ordered 100 copies of the airliner variant, though only 43 were completed while just seven were assembled and flown. The Vimy Commercial also served as a troop transport known as the Vernon.

April 14, 1962 – The first flight of the Bristol 188. Nicknamed the “Flaming Pencil,” the Bristol 188 was a research aircraft developed to explore supersonic flight. Bristol produced three 188s in response to Operational Requirement 330, which called for a Mach 3 reconnaissance aircraft. The project was plagued with problems, most notably fuel consumption issues which did not allow the aircraft to fly supersonically long enough to test the effects on the airframe. The 188 could not reach Mach 2, and the nearly 300 mph take off speed hampered the test program. However, much of what was learned with the 188 was applied later in the development of the Concorde supersonic transport.

April 14, 1959 – The first flight of the Grumman OV-1 Mohawk. The Mohawk began as joint US Army/Marine Corps project to replace the Cessna L-19 Bird Dog for battlefield reconnaissance while also adding expanded attack capabilities. Among the missions for the two-man crew were forward air control, artillery spotting, emergency resupply, and naval target spotting. The Mohawk was also designed to operate from short, unimproved runways as well as US Navy escort carriers, and the OV-1's two Lycoming T53 turboprop engines gave the aircraft a top speed of 305 mph. The Mohawk entered service with the US Army in 1959, and saw action during the Vietnam War, where 65 were lost to accidents but only one to enemy fire. OV-1s continued flying as late as the Gulf War before retirement in 1996. A total of 380 were built.

April 14, 1947 – The first flight of the Douglas D-558-1 Skystreak, a turbojet-powered research aircraft built as a joint project between the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) and the US Navy. The Skystreak was the first in a planned series of three aircraft designed to explore the regime of supersonic flight, though the second phase was canceled in favor of the swept wing D-558-2 Skyrocket. Douglas built three examples of the Skystreak and, in just four months, it had broken the previous speed record set by the German Me 163 Komet rocket plane. Though overshadowed by the supersonic Bell X-1, the Skystreak nevertheless provided important data in the realm of transonic flight which was used in the design of future supersonic aircraft.

April 15, 1986 – United States Air Force, Navy, and Marine Corps aircraft attack Libya in Operation El Dorado Canyon. In response to the bombing that killed three and injured more than 200 others in a Berlin discotheque frequented by US soldiers, the United States launched airstrikes against Libyan president Muammar Gaddafi after Libya was suspected of orchestrating the Berlin bombing. Eighteen F-111F tactical bombers and four EF-111A Raven electronic warfare (EW) aircraft flew from bases in Britain combined with attack and EW aircraft from the carriers USS Saratoga, USS America and USS Coral Sea sailing off the Libyan coast in the Gulf of Sidra. The aircraft struck five targets at 2:00 am local time, with the hope that Libya would be deterred from future terrorist attacks. Gaddafi himself may also have been a target. Libya reported at least 40 casualties from the bombing, including one who may have been the Gaddafi’s infant daughter. Numerous aircraft and radar stations were also attacked. Gaddafi escaped injury. One American F-111 was shot down with the loss of its two-man crew.

April 15, 1965 – The first flight of the Aérospatiale SA 330 Puma, a medium transport/utility helicopter originally developed by Sud Aviation to meet a requirement by the French Army for a helicopter that could carry 20 troops or cargo in all weather conditions. After the purchase of the Puma by the Royal Air Force, France and England entered into a production partnership that eventually included Romania and South Africa. The Puma has seen action in numerous conflicts, including the Falklands War and the First Gulf War, and is also a popular civilian transport helicopter, particularly for offshore oil corporations.

April 16, 1988 – The first flight of the McDonnell Douglas T-45 Goshawk, a fully carrier-capable trainer developed from the British Aerospace Hawk Mk 60. The Goshawk entered service in 1991 and eventually replaced the older North American T-2 Buckeye and Douglas TA-4 Skyhawk for the US Navy and US Marine Corps. The T-45 provides a platform for intermediate and advanced strike pilot training, with aircraft currently based at NAS Meridian in Mississippi and NAS Kingsville in Texas. Though the US Air Force has selected the Boeing T-X as its next generation trainer, the Navy plans to keep flying the Goshawk until at least 2035.

April 16, 1972 – The launch of Apollo 16, the tenth manned mission of the Apollo program and the fifth mission to land astronauts on the Moon. Commander John Young and Lunar Module Pilot Charles Duke spent 71 hours on the lunar surface, where they conducted three moonwalks and collected over 200 pounds of lunar samples, some of which served to disprove the theories about volcanic origins for some of the Moon’s features. Young and Duke also drove the second Lunar Roving Vehicle (LRV) a total of 16.6 miles. Command Module Pilot Ken Mattingly completed 64 orbits of the Moon in the Command Module, and performed a spacewalk on the return flight to retrieve film capsules from the exterior of the Service Module. There would be just one more launch in the Apollo program, Apollo 17, eight months later. Apollo 16 returned to Earth on April 27, 1972.

April 16, 1949 – The first flight of the Lockheed F-94 Starfire. Following the failure of the Curtiss-Wright XF-87 Blackhawk, the Starfire was hastily developed from the Lockheed T-33 Shooting Star. The all-weather day/night interceptor entered service in 1950 to replace both the Northrop F-61 Black Widow and the North American F-82 Twin Mustang, and was the first operational US Air Force fighter to employ an afterburning engine and the first all-weather fighter to see service in the Korean War. Though produced in large numbers, the Starfire served for just eight years before being replaced in the interceptor role by the Northrop F-89 Scorpion and North American F-86D Sabre.

April 16, 1912 – Harriet Quimby becomes the first woman to fly across the English Channel. In 1911, Quimby became the first woman to earn a pilot’s license in the United States, and her exploits were an inspiration to many women of her day who railed against male-dominated society. Quimby’s cross-Channel flight was unfortunately overshadowed by news of the sinking of the RMS Titanic just one day after her historic flight. Quimby died on July 1, 1912 when, for unknown reasons, her Blériot XI monoplane suddenly pitched forward, ejecting both her and her passenger at an altitude of 1,500 feet. Ironically, the plane came to earth relatively undamaged.

Connecting Flights

If you enjoy these Aviation History posts, please let me know in the comments. And if you missed any of the past articles, you can find them all at Planelopnik History. You can also find more stories about aviation, aviators and airplane oddities at Wingspan.