Welcome to This Date in Aviation History, getting of you caught up on milestones, important historical events and people in aviation from May 29 through May 31.

May 29, 1940 – The first flight of the Vought F4U Corsair. In the world of a fighter pilot, speed is life. Not only does speed give a pilot an advantage over their opponent, it also gives them the ability to run to safety when outnumbered. So, when the US Navy Bureau of Aeronautics (BuAer) requested proposals for a new single-engine fighter in early 1938, they stipulated that the fighter must provide the maximum speed obtainable, which meant that it would have to be fitted with the most powerful engine available along with the largest propeller.

Following the unsuccessful Vought V-141/V-143 (which were actually developed from an aircraft originally designed by Northrop), Vought design team leader Rex Beisel took the same basic design of the earlier aircraft but made it considerably larger and gave the new XF4U-1 a prototype 18-cylinder Pratt & Whitney XR-2800 Double Wasp twin row radial engine. This marked the first time that the Double Wasp was fitted in an aircraft, and that engine would go on to power some of the most iconic military aircraft in history. In the early Corsair, the Double Wasp provided 1,805 hp and, when mated with the largest propeller ever fitted on a fighter up to that time, the Corsair became the first single-engine US fighter to exceed 400 mph in level flight. And it was that large propeller that gave the Corsair its iconic inverted gull wing. The shape of the wing actually had nothing at to all do with aerodynamics or performance; rather, the bend in the wing was to provide ground clearance for the huge propeller while using shorter landing struts. The fully retractable oleo struts were also a first for a US Navy fighter, and the anhedral center portion of the wing also housed the Corsair’s oil coolers.

By the time the F4U-1 entered production, some significant changes had taken place in the design. The original armament of two .30 caliber machine guns mounted in the engine cowling and two .50 caliber machine guns in the wings gave way to six .50 caliber guns in the wings. But with all the armament in the wings, the fuel had to be placed somewhere else. So the cockpit was moved aft and the wing fuel tanks were relocated to a larger self-sealing tank ahead of the cockpit. Thus, another practical design consideration was responsible for the Corsair’s iconic long nose which preserved the aircraft’s center of gravity. A new more powerful Double Wasp engine now provided the Corsair with 2,000 hp, while later production models added water injection for still more power, a plexiglass canopy, and a raised seat to aid visibility over the long nose.

But even with the raised seat, Corsair pilots still had trouble seeing over the nose during carrier landings, and this led to the US Navy’s initial refusal to accept the Corsair for carrier operations. It wasn’t until the British devised a turning landing procedure that allowed the pilot to see the deck until the last part of the landing pattern that the Navy accepted it as a carrier fighter. Since the Navy already had the Grumman F6F Hellcat, which was powered by the same Double Wasp engine, the Corsair became the primary weapon of land-based US Marine Corps units who flew the F4U with devastating effectiveness in the Pacific Theater, where the Japanese called it “Whistling Death.” Marine Corps pilots proved that the Corsair could be an effective ground attack platform, particularly in the close air support mission (CAS) in support of Marine landing forces.

While many WWII fighters were retired at the end of the war in favor of new turbojet fighters, the Corsair’s speed, power and range ensured its continued service with the Navy and Marine Corps. The Corsair saw extensive action in the Korean War, where it was used primarily in the CAS role and, though outclassed by the new Russian jet fighters, Marine pilot Capt. Jesse Folmar nevertheless managed to shoot down a MiG-15 while flying a Corsair. The Corsair proved to be a robust yet flexible platform, and no less than 16 variants were developed throughout its service life, including the addition of cannon armament, a wing-mounted radar pod for night fighting, and the addition of superchargers. After WWII, the Corsair also proved popular on the air race circuit. Over 12,500 Corsairs were built between 1942-1953, the longest production run for any American piston-powered fighter, so many that Vought had to enlist the aid of Goodyear and Brewster to help build the fighter during the war, though poor production quality meant that none of the Brewster-built Corsairs were sent to battle. Of that number, roughly 45 remain airworthy or are undergoing restoration.

May 29, 1935 – The first flight of the Messerschmitt Bf 109. In the years leading up to WWII, Germany was working all out to rebuild its air force following the harsh restrictions placed on the country by the Treaty of Versailles that brought an end to WWI. Though Germany was technically restricted from creating any new weapons of war, civilian designers nevertheless forged ahead with the development of new aircraft that could easily take on fighting roles. When the Bf 109 took its first flight, it heralded the end of the biplane era and the ascendancy of the monoplane fighter.

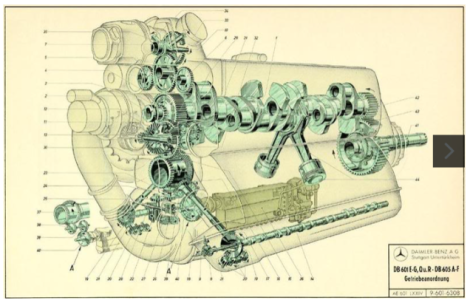

One of the first truly modern fighters of its day, the Bf 109 (often erroneously called the Me 109) featured the first operational use of all-metal monocoque construction, retractable landing gear, and an enclosed cockpit. It was developed as one part of a four-part requirement for new military aircraft put forth by the Reichsluftfahrtministerium (Ministry of Aviation) in 1933. The requirement called for a single-seat fighter with a top speed of 250 mph and a rate of climb that would allow the fighter to reach 20,000 feet in a minimum of 17 minutes. Arado, Heinkel, Focke-Wulf and the Bayerische Flugzeugwerke (Bf), led by Willy Messerschmitt, all submitted designs, with the Messerschmitt aircraft declared the winner as it offered a higher speed, better rate of climb, and superior diving characteristics. Messerschmitt’s new fighter was powered by the new Junkers Jumo 210 inverted V-12 engine but, not without a touch of irony, the prototype’s first flight was powered by a British-made Rolls-Royce Kestrel mounted upright, since the Jumo was not yet ready. The use of inverted engines provided certain benefits over the more traditional mounting, such as improved visibility over a narrower nose, greater ease of maintenance in the field, and a lower center of mass that improved handling. It also allowed for the placement of a cannon that fired through the propeller spinner, with the propeller turned by a series of gears. The Jumo was used primarily in pre-war fighters, and was replaced in wartime production by the Daimler-Benz DB 601 and DB 605.

The Bf 109 was an immediate success, setting numerous speed records in the years prior to the war, and a specially prepared Bf 109 set a speed record for piston aircraft that stood until 1969. The 109 saw its first action in the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) in support of Franco’s fascist government, which the Luftwaffe used as a dress rehearsal for the coming invasion of Poland. Development of the 109 continued throughout the war, with refinements of the design to increase handling and the installation of ever more powerful engines to increase speed. Though more advanced fighters, such as the radial-engined Focke-Wulf Fw 190, were introduced throughout the conflict, the Bf 109 remained the backbone of the Luftwaffe fighter force throughout the war, and proved very effective, particularly against more poorly trained Russian pilots on the Eastern Front. Bf 109 pilots accounted for more aerial victories than any other aircraft in the war, with the highest scoring ace in history, Erich Hartmann, claiming an astonishing 352 victories, most against Russia, and Hans-Joachim Marseille, fighting against significantly better opponents in North Africa, scoring 154 victories.

The 109 was widely exported to countries allied to Germany and, though most German aircraft were retired after the war, the 109 continued to serve foreign air forces, particularly the Swiss and Finnish air forces, into the mid-1950s. By any metric, the Bf 109 was a remarkable fighter, but perhaps most telling is the sheer number of aircraft built. By the end of production, nearly 34,000 Bf 109s of all types had been produced, making it the second-most produced combat aircraft in history behind the Russian Ilyushin Il-2 Sturmovik (36,183).

May 30, 1958 – The first flight of the Douglas DC-8. By the end of WWII, Douglas Aircraft held a commanding lead in the production of piston-powered airliners, a dominance that reached all the way back to the early 1930s with the DC-2 (DC stands for Douglas Commercial). But even though WWII heralded the dawn of the jet age, Douglas saw no need to rush headlong into the new technology. The company was still well-placed in the airliner market with their extremely successful DC-6, and the DC-7, its final piston airliner, was still in development and wouldn’t take its maiden flight until 1953. De Havilland had produced the world’s first turbojet-powered airliner with the Comet, but a series of fatal crashes led airlines to shy away from jet airliners, even though the Comet crashes were traced to metal fatigue around its large, square windows and had nothing at all to do with its turbojet engines.

But by 1950, Douglas was feeling the heat from their primary competitor. Inspired by the success of their B-47 Stratojet bomber, Boeing had begun work on their own jet powered airliner, and rolled out the 367-80 (Dash 80) in 1954. Though it was originally designed for the US Air Force as a jet-powered aerial tanker and adopted as the KC-135 Stratotanker, the implications for the commercial airline industry were clear. In 1952, Douglas had begun their own studies for the development of a four-engine jetliner, also hoping to compete for a lucrative defense contract. Ultimately left out of the tanker competition, Douglas moved ahead with their airliner design and announced the DC-8 in 1955. Following consultations with the airlines, they modified their prototype to allow for six-abreast seating and offered four different versions of the jetliner, though in a fateful decision, the variants only offered options for different engine or fuel loads. Douglas refused to offer the DC-8 in any other fuselage lengths, a decision that ultimately hampered sales when pitted against the Boeing 707. Despite the promise of the new jet airliner, airlines were still lukewarm to the idea, as the turboprop airliner used less fuel and was quieter. It wasn’t until Pan Am announced that they would buy both the Boeing and the Douglas aircraft that airlines finally went all-in on turbojet airliners.

The DC-8 entered service with Delta Air Lines and United Airlines in 1959, though Douglas’ decision to limit production to a single fuselage size led the airlines also to purchase similar but more flexible offerings from Boeing, as well as Convair, who offered their 880 airliner. It wasn’t until 1965 that Douglas finally offered a stretched DC-8, called the Super Sixty. The lengthened airliner now accommodated up to 269 passengers, a mark that was not surpassed until the arrival of the Boeing 747 in 1970. And even though the 707 is by far the most well-known airliner of the era, Douglas (now McDonnell Douglas following the merger of the two companies in 1967) would have the last laugh. While nearly twice the number of 707s and 720 variants were produced by Boeing, just 80 remained in service by 2002. The DC-8, however, which proved to be an excellent cargo aircraft after its passenger-carrying days were over, could boast 200 aircraft still in service. And by 2013, 36 DC-8s were still in service worldwide.

Short Takeoff

May 29, 1951 – Capt. Charles Blair makes the first nonstop solo flight over the North Pole. After setting a speed record flying nonstop from New York to London at an average speed of 446 mph earlier in the same year, Blair set his sights on crossing the North Pole. He departed from Bardufoss, Norway in his North American P-51C Mustang named Excalibur III and flew nonstop to Fairbanks, Alaska, a flight that covered 3,260 miles. Blair was awarded both the prestigious Harmon Trophy and the Gold Medal of the Norwegian Aero Club. Blair was killed in 1978 in the crash of a Grumman Goose he was piloting for Antilles Air Boats, and the Excalibur III is on display at the Smithsonian’s Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in Virginia.

May 29, 1944 – The aircraft carrier USS Block Island is torpedoed near the Azores. Block Island (CVE-21) was a Bogue-class escort carrier commissioned on March 8, 1943 that originally entered service as an aircraft ferry and made two trips between New York City and Belfast before WWII. During the war, she operated as part of a hunter-killer group and took part in four anti-submarine cruises that resulted in the sinking of four German U-boats. While sailing off the coast of the Azores, Block Island was struck by three torpedoes from the German submarine U-549, which was in turn sunk by American destroyers. Remarkably, only six sailors were lost in the attack, with the other 951 picked up by members of the battle group. Block Island was the only American carrier lost in the Atlantic during WWII.

May 29, 1934 – The Collier Trophy is awarded to the Hamilton Standard Propeller Company for development of the controllable-pitch propeller. The controllable-pitch propeller (or variabile-pitch) is one in which the blades can be rotated along their long axis to alter the blades’ angle of attack as they pass through the air, increasing the propeller’s efficiency. The hydraulically actuated propeller designed by Hamilton Standard allowed the pilot to have direct control over the propeller’s pitch, and was a significant advance in aircraft technology. For their work, the company received the Collier Trophy, which is awarded for “the greatest achievement in aeronautics or astronautics in America, with respect to improving the performance, efficiency, and safety of air or space vehicles, the value of which has been thoroughly demonstrated by actual use during the preceding year.”

May 30, 1972 – The first flight of the Northrop YA-9, the unsuccessful competitor against the Fairchild Republic YA-10 (the eventual A-10 Thunderbolt II) for a dedicated close air support (CAS) aircraft. Both aircraft were designed around the 30mm General Electric GAU-8 Avenger rotary cannon, though the Northrop prototype was armed with 20mm M61 Vulcan gun as the GAU-8 was still under development. While both designs showed promise, the YA-10 was selected after a fly-off between the two. Northrop built two prototypes, both of which were given to NASA for further flight testing after the competition. One of the prototypes is on display at March Field Air Museum, and the other awaits restoration at Edwards Air Force Base in California.

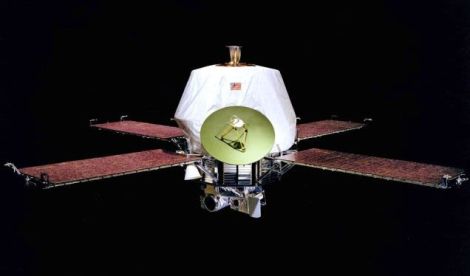

May 30, 1971 – The launch of Mariner 9, an unmanned space probe launched by NASA to explore Mars and the first spacecraft to orbit another planet. Part of the Mariner program, Mariner 9 was launched from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station atop an Atlas-Centaur rocket and reached Mars on November 14, 1971, beating similar Russian probes by less than a month. Mariner 9's primary mission was to map the Martian surface, and the spacecraft also included a radiometer to detect volcanic activity. Before deactivation on October 27, 1972, Mariner 9 returned 7,329 images of Mars, as well as important data on the composition of the Martian atmosphere. Mariner 9 remains in Mars orbit, and is expected to fall from orbit and burn up in the Martian atmosphere sometime in 2022.

May 30, 1948 – The first flight of the Martin P5M Marlin, a flying boat developed by the Glenn L. Martin Company as a maritime patrol aircraft based on the earlier Martin PBM Mariner. The Marlin was notable for its use of a gull wing, which raised the engines higher above the surface of the water to keep them clear of the ocean spray. Later production models were modified with a T-tail to place the elevators higher above the water as well, and anti-submarine warfare variants were fitted with a magnetic anomaly detector (MAD) boom to detect submarines. The Marlin entered service in 1952 and saw action in the Vietnam War, performing the last flying boat maritime patrols carried out by the US Navy. The Marlin also served with the US Coast Guard and French Navy, and was retired in 1967 after production of 285 aircraft.

May 30, 1942 – The first bombing mission of Operation Millennium. During WWII, the US and Britain were convinced of the effectiveness of heavy strategic bombing against German cities. Following the principles set forth by Italian general Giulio Douhet, the Allies believed that heavy bombardment of civilian centers would hasten the end of war by breaking the morale of the population. Gathering together every flyable bomber they could muster, including many obsolete aircraft, the RAF launched Operation Millennium against the German city of Cologne in the hopes of putting over 1,000 bombers over the target in a single mission. The streams of bombers flew over the city for 90 minutes and dropped 1,500 tons of bombs into the city center. More so-called 1,000 bomber raids were carried out against other cities, but strategic bombing never had the desired effect on civilian morale, and German factory production actually increased steadily throughout the war despite the concentrated bombing effort.

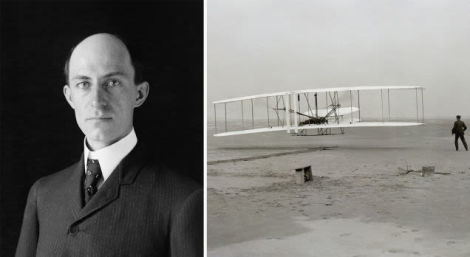

May 30, 1912 – The death of Wilbur Wright. Following the successful first flight at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina in 1903, the Wright Brothers worked tirelessly to improve their machine, secure investors, and protect their intellectual property. They also had to establish the fact that they were first at powered flight against mounting skepticism at home and abroad. The brothers started the Wright Company in 1909, but Wilbur spent many of his final years shuttling between the US and Europe fighting to protect their patents. Perhaps due to the strain of those trips, Wilbur fell ill with typhoid fever in May 1912 and died soon after at the age of 45. Following Wilbur’s death, Orville took over the leadership of their company before selling his stake in 1915, and died in 1948 at the age of 76, having lived from the first flight into the supersonic age of aviation.

May 31, 1991 – The first flight of the Pilatus PC-12, a turboprop passenger and cargo aircraft designed primarily for corporate use and regional airlines. The PC-12 is powered by a single Pratt & Whitney Canada PT6 turboprop that provides a cruising speed of 312 mph and a range of over 1,700 miles with a full complement of nine passengers. The PC-12 has proven to be a tremendous success, and is the best selling pressurized single-turbine aircraft in the world. Over 1,500 have been built, and the aircraft remains in production. The bulk of sales have been to the civilian market, though the PC-12 does serve government agencies and militaries around the world, including the US Air Force, where it is known as the U-28A.

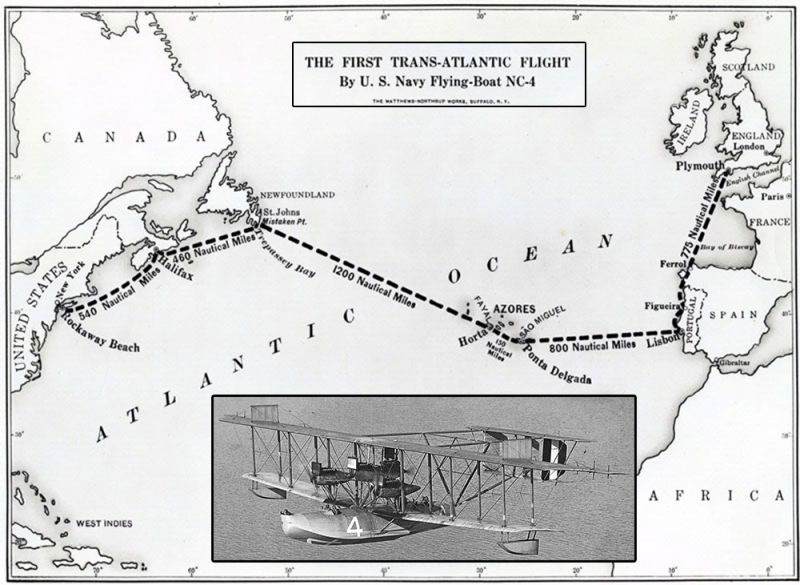

May 31, 1919 – US Navy Lt. Cdr. A. C. Read and his crew complete the first transatlantic flight. Three Curtiss NC flying boats—NC-1, NC-3 and NC-4—set out from the naval air station at Rockaway Beach, New York on May 8 with Plymouth, England as their ultimate destination. Flying first to Nova Scotia then Newfoundland, the three aircraft with their six-man crews turned across the Atlantic in the longest leg of the flight, 1,200 miles to the port of Horta in the Azores, roughly two-thirds of the way to Portugal. To aid in navigation and provide rescue if necessary, 21 US Navy ships were stationed along the line of flight, while a second line of ships marked the route from the Azores to Lisbon, Portugal. NC-3 got lost and set down off the Azores. Her crew was rescued, but the plane later sank. NC-1 also got separated and set down in the ocean, but rough seas prevented the crew from taking off. They finally sailed their aircraft under its own power into Horta on May 19. NC-4 was the only aircraft to arrive in Horta after 15 hours in the air, and finally made it to Plymouth on May 31 after 24 days and 4,000 miles. Roughly two weeks later, British aviators John Alcock and Arthur Brown completed the first non-stop flight across the Atlantic.

Connecting Flights

If you enjoy these Aviation History posts, please let me know in the comments. And if you missed any of the past articles, you can find them all at Planelopnik History. You can also find more stories about aviation, aviators and airplane oddities at Wingspan.