Welcome to This Date in Aviation History, getting of you caught up on milestones, important historical events and people in aviation from July 20 through July 23.

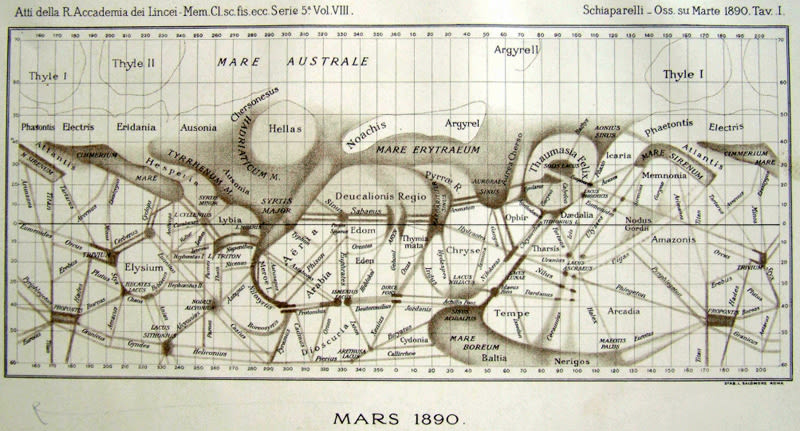

July 20, 1976 – Viking 1 lands on Mars. By the late 1800s, theories about Mars, particularly whether or not there was life on the Red Planet, were at a fever pitch. Astronomers made detailed maps of the planet based on their observations through telescopes, and some determined that the features they were seeing on the planet’s surface were undoubtedly canals built for transportation by Martian inhabitants. H.G. Wells wrote one of the great seminal works of science fiction when he published The War of the Worlds in 1898, chronicling the harrowing tale of a Martian invasion of Earth. But looking at a distant world through a telescope only gave scientists so much information. Ultimately, there is no substitution for actually going to the planet and making firsthand scientific observations.

Spurred on by the Space Race, the Soviets launched the first of a series of probes to Mars in 1960, though it was not until 1965 that NASA’s Mariner 4 performed the first successful fly-by of the planet. Six years later, Mariner 9 became the first space probe to orbit another planet when it circled Mars and returned the first photographs of the Martian surface. The Russians were the first to put a spacecraft on the planet, but problems with the landers meant that no useful data was returned. NASA’s efforts to put a lander on Mars began with the Voyager Mars Program, which planned to use rockets and landers based on those used in the Apollo program. Though that initiative was canceled in 1968, the impetus to go to Mars remained, and the project became known as Viking, a much less complex—and less expensive—alternative.

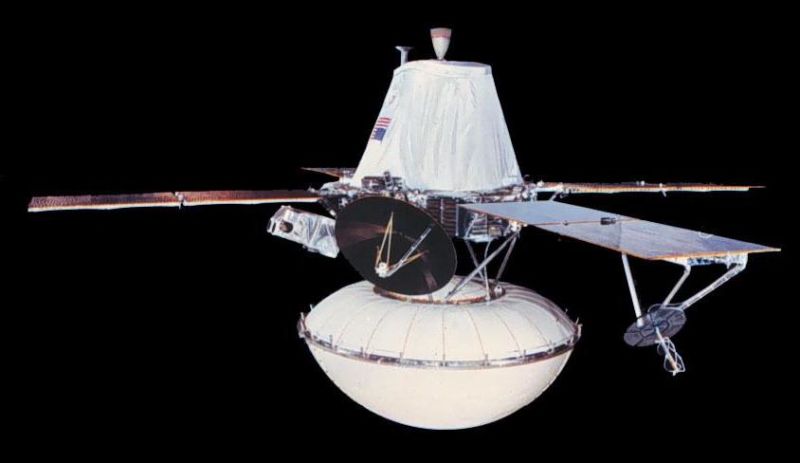

For Viking, NASA launched two probes, Viking 1 and Viking 2. Each spacecraft was composed an Orbiter and a Lander. Not only was the Orbiter designed to carry the Lander, but it also had its own important functions in the mission. It made scientific observations of the Martian surface with its cameras, looked for water vapor with its infrared spectrometer, and created a thermal map of the surface with its infrared radiometer. The Orbiter also served as a communication relay between the Lander and Earth. The Lander was a three-legged assemblage of cameras and instruments that descended penetrated the Martian atmosphere protected by a heat shield, and was then slowed by parachutes before touching down on the planet surface. Viking 1 was launched from Cape Canaveral, Florida on August 20, 1975 atop a Titan IIIE/Centaurrocket and, after a 10-month journey, began orbiting Mars on June 19, 1976. Viking 1's sister ship, Viking 2, launched a month later. After Viking 1 reached Mars, it spent its first month in orbit making observations and selecting a safe spot for the Lander to touch down. Then, on July 20, the Lander separated from the Orbiter and touched down on a smooth Martian plain known as Chryse Planitia (Golden Plain).

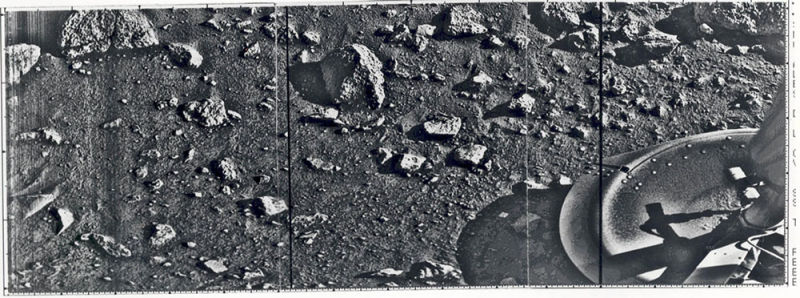

Viking 1 didn’t find any signs of technologically advanced cultures planning to invade the Earth, nor any signs of life at all. However, the first clear photos ever taken from the Martian surface showed geological forms such as valleys and erosional features on volcanoes that indicated the presence of large amounts of water at one time in Mars’ history. This discovery fundamentally changed scientists’ theories about the history of Mars, and influenced future missions in the search for water in the form of liquid or ice. The Viking 1 Orbiter powered down on August 7, 1980 after 1,489 orbits of Mars, and the Lander made its final transmission to Earth on November 11, 1982. Its 2,307 days of service set a record for surface duration that was only broken by the rover Opportunity in 2010. Viking 2 landed on Mars on September 3, 1976, and operated for 1,316 Martian days before its batteries failed.

July 20, 1951 – The first flight of the Hawker Hunter. The history of aviation is a story of extraordinarily rapid development, but perhaps there was no greater sea change in flight than the introduction of the jet engine during the Second World War. This fundamental change in aviation power not only brought with it new realms of speed, it also brought about significant changes in airplane design, particularly the use of swept wings. Though the jet engine was a product of technological advances before and during the war, the idea of sweeping the wings dates back to the earliest days of aviation, and significant theoretical work was done in the 1930s by Adolf Busemann. Despite this, the first operational jet-powered aircraft were all straight-wing designs, essentially piston aircraft given a new power plant.

The British introduced the first Allies’ first (and only) operational jet of WWII with the Gloster Meteor in 1944, and Hawker followed in 1947 with the Hawker Sea Hawk, which was essentially a jet-powered development of earlier piston-powered designs. In 1946, the British Air Ministry issued specification 38/46 which called for an investigation into the flight characteristics of a swept wing aircraft at low speeds. Hakwer responded with a swept-wing variant of the Sea Hawk, the P.1052, which had been designed by Hawker’s chief designer Sydney Camm. Only two were built, but development continued with the Hawker P.1081, and by now the characteristic and classic lines of the Hunter were beginning to emerge. Later that year, the British Air Ministry issued a specification for a new daytime, jet-powered interceptor to be powered by the Rolls-Royce Avonturbojet, a more compact and more powerful engine that provided as much power as the two combined Rolls-Royce Derwent engines used on the Meteor. Hawker responded to the specification with the P.1067, a graceful, swept-wing design with a nose air intake, but Camm moved the intakes to the wing roots to allow for the installation of a nose-mounted radar.

Two prototypes were built, and what was now known as the Hawker Hunter was ordered into production in 1950, the first jet-powered aircraft by Hawker to enter service with the RAF and the first British fighter with truly transonicperformance. Hawker was competing with the Supermarine Swift, an aircraft of similar design, but the Hunter proved to have significantly better performance, and was the first RAF aircraft capable of keeping pace with the English Electric Canberrra bomber. The Hunter was armed with four 30mm ADEN cannons, could carry 7,400 pounds or ordnance on external hardpoints, and had a top speed of Mach 0.94. It entered service with the RAF in July 1954, replacing the Meteor, the Canadair Sabre and the de Havilland Venom, and saw its first action escorting Canberra bombers during the Suez Crisis in 1956. The Hunter also proved popular with flight demonstration squadrons such as the Patrouille Suisseand the RAF’s Black Arrows, which set a world record by performing a loop with 22 Hunters in formation. With the introduction of the supersonic English Electric Lighting in 1959, the Hunter’s role changed from interceptor to ground attack and reconnaissance. Nearly 2,000 Hunters were produced, and roughly half of those were sold to 21 export customers around the world. The Hunter served the RAF for over 30 years, and some were flying for international customers as late as 1996. A number of the graceful fighters can still be seen flying the air show circuit in the hands of private collectors.

July 23, 1983 – Air Canada Flight 143, known as the Gimli Glider, runs out of fuel over Manitoba. When driving a car, most people rarely give the fuel gauge more than a passing glance, and rely on a warning light to alert them when the level is low. And unless you’re driving across the desert, you can pull over at any convenient gas station and top up. Driving across the country requires a bit more attention, as gas stations can be spaced farther apart, and perhaps even a little bit of math might be involved to figure out if there’s enough fuel to reach the next town or if you need to fill up now. And even then, running out of gas on the road is generally more of an inconvenience than a life-and-death situation. But calculating the amount of fuel to put in a transcontinental airliner is a much more involved task, and one that actually could be a matter of life or death. The aircrew must make calculations for the weight of the aircraft at takeoff, taxiing time, the distance and altitude of the flight, the rate at which the fuel burns off, and they must make sure that there is enough fuel in reserve to divert to another airport. The vast majority of the time, the pilots get it right, and with fuel to spare. But in the case of Air Canada Flight 143, which came to be known as the Gimli Glider, the pilots got it completely wrong.

Air Canada Flight 143 was a scheduled flight from Montreal to Edmonton when, at 41,000 feet, pilots Captain Robert Pearson and First Office Maurice Quintal were alerted to fuel pressure problem onboard their Boeing 767-233 (C-GAUN). Due to an electronic fault, the airliner’s fuel gauges weren’t working, but the pilots assumed that they had plenty of fuel based on the calculations they had made on the ground before the flight. In reality, they took off with half the amount of fuel necessary to reach their destination. Soon after the alarm, both engines quit, the 767 lost all power and the majority of the instrument panels went dark. The pilots found themselves at the controls of world’s largest glider, a situation for which neither of them had ever trained.

With the aid of ground controllers, the crew determined that their best option would be an emergency landing at Canadian Forces Base Gimli, a former Royal Canadian Air Force air station. However, though the runways were still mostly intact, the station was no longer active, and much of it had been turned into an industrial park and racetrack. And there was a race being held on the track at the time. The pilots performed a gravity drop of the landing gear, but the nose wheel failed to lock and, despite having no hydraulic power and limited electricity generated by an external turbine, the pilots still managed to land safely. A small fire in the nose of the aircraft was extinguished by race safety personnel at the scene, and all passengers and crew exited the plane safely, though some passengers were injured when the safety slides at the rear of the craft weren’t long enough to reach the ground due to the collapsed nose gear.

Investigators discovered that the fuel exhaustion was caused by a combination of miscommunication between the cockpit crew and maintenance personnel, fuel gauges that were disconnected or not functioning properly, and fuel calculations that had been made in pounds instead of kilograms, a result Canada’s ongoing transition from the Imperial to the metric system. For their part in the incorrect fuel calculation, Captain Pearson and FO Quintal were initially found to be partially at fault for the incident. Pearson was demoted for six months, and Quintal was suspended for two weeks. Maintenance personnel were also suspended. Despite these punitive measures, the flight crew was awarded the first ever Féderation Aéronautique Internationale Diploma for Outstanding Airmanship in 1985, and FO Quintal was eventually promoted to captain. The Gimli Glider was repaired and returned to service, and took its final flight on January 24, 2008, after which it was retired to storage in the Mojave Desert. When no buyers came forward to purchase the 767, it was dismantled, and aluminum from the plane was turned into souvenir keychains.

Short Takeoff

July 20, 1925 – The first flight of the Boeing Model 40, a mailplane developed as part of a requirement by the US Post Office to replace the Airco DH-4. After the Model 40 lost the airmail contract to the Douglas M-2, Boeing revised the design to make use of the Pratt & Whitney R-1340 Wasp radial engine, which weighed less than the original Liberty V-12 engine that had been stipulated by the Post Office. Boeing also strengthened and lengthened the fuselage to accommodate two passengers, with subsequent models having room four passengers. Thus, the Model 40 became the first passenger airplane to enter production for Boeing and, in 1927, Boeing Air Transport, the precursor to United Airlines, began operations between San Francisco and Chicago. Boeing produced 80 Model 40s, and one remains airworthy today.

July 21, 2011 – The Shuttle Atlantis lands in Florida after mission STS-135, marking the final mission of the Space Shuttle Program. The Space Shuttle program was announced during the Nixon Administration as a reusable spacecraft to help reduce the cost of going to space. The first Shuttle, Enterprise, was used for testing and never went to space. NASA built five operational orbiters, Columbia, Challenger, Discovery, Atlantis, and Endeavour, and Columbia launched on the first mission to orbit, STS-1, on April 12, 1981. Over the course of 135 missions spanning 30 years, the Shuttle fleet transported over 3.5 million pounds of cargo into space and completed 20,830 orbits. Shuttle astronauts also deployed 180 satellites and components for the construction of the International Space Station (ISS). Two Shuttles, Challenger and Columbia, were lost to accidents that claimed the life of 14 astronauts. The remaining Shuttles were distributed to aviation museums around the country.

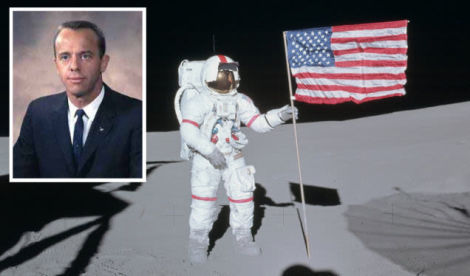

July 21, 1998 – The death of Alan Shepard. Born on November 18, 1923 in Derry, New Hampshire, Shepard has the distinction of being the first American to go to space when he flew a suborbital mission on Freedom 7, and he became the oldest astronaut (at the time) when he commanded the Apollo 14 mission and piloted the lunar lander Antares to the most accurate landing of all the Apollo missions. A diagnosis of Ménière’s disease, a condition that affects the inner ear, ended Shepard’s flying career, but he continued to serve as the Chief of the Astronaut Office until 1969. Shepard was promoted to the rank of rear admiral in the US Navy, the first astronaut to reach that rank, and retired from the US Navy and NASA in 1974.

July 21, 1947 – The first flight of the Aero Ae-45, a twin engine civil utility aircraft and the first aircraft to be produced by Czechoslovakia following WWII. The Ae 45 was powered by a pair of Walter M 332 air-cooled 4-cylinder engines, and could carry one pilot with up to four passengers at a cruising speed of 155 mph. The Ae 45 proved to be very popular, and was widely exported to Eastern Bloc countries and allies of the Soviet Union, as well as Italy and Switzerland. Nearly 600 were produced from 1951-1963.

July 21, 1946 – The first landing by a purely jet-powered aircraft aboard an American aircraft carrier. Though the unfortunately named Ryan FR Fireballmixed propulsion fighter actually made the first jet-powered carrier landing, it did so only because its radial engine had failed. The McDonnell FH Phantom, which first flew on January 26, 1945, made the first true jet-powered landing when it touched down aboard the carrier USS Franklin D. Roosevelt (CV 42) near Norfolk, Virginia. US Navy fighter squadron VF-17A, flying the FH Phantom, became the US Navy’s first operational jet carrier squadron in 1948, flying from USS Saipan (CVL 48).

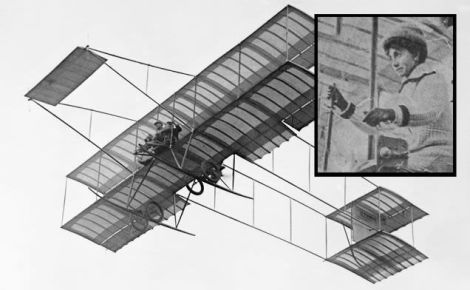

July 21, 1911 – Denise Moore becomes the first woman to die in an airplane crash. Moore’s real name was E. Jane-Wright, but she flew under a pseudonym because flying wasn’t considered a proper pastime for women and she wanted to conceal her hobby from her family. At the time of her death, Moore was learning to fly at the Henry Farman aviation school at Étampes, France, and was flying one of Farman’s aircraft, most likely a Farman III. At an altitude of 150 feet, Moore lost control of the airplane and fell to her death when the airplane inverted.

July 22, 1959 – The first “jetway” in the United States is installed at Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport in Atlanta.* While modern travelers are familiar with the extendable tunnel that leads passengers to their airplane, boarding an airliner in the early days of commercial aviation meant crossing the tarmac or muddy field and climbing stairs, often at the mercy of winds, rain or snow. Engineer Frank Der Yuen patented an “apparatus for facilitating the loading and unloading of passengers and cargo,” and the trademarked name jetway has now become synonymous with any passenger boarding bridge (PBB) as it is officially known. Capable of being extended, retracted, moved, raised or lowered to accommodate most any airliner, the jetway is now a fixture at most airports around the world, and provides a safe and comfortable way for air travelers to board their plane.

* The actual location of the first jetway is not certain, with some accounts placing it at either O’Hare Airport in Chicago, Los Angeles International Airport, LaGuardia Airport in New York or San Francisco International Airport.

July 22, 1955 – The first flight of the Republic XF-84H “Thunderscreech,” a development of the Republic F-84F Thunderstreak intended to provide the US Navy with a fighter that could take off without a catapult. The XF-84H had a 5,850 hp Allison XT40 turboprop located behind the cockpit that turned a propeller in the nose through a drive shaft and which also provided thrust through its exhaust. An afterburner was fitted but never used. While the concept showed unprecedented acceleration, the aircraft took 30 minutes to warm up, and the supersonic propeller, turning at a constant Mach 1.18, caused continuous sonic booms that created a shock wave which induced acute nausea and headaches in the ground crew. The XF-84H was also one of the loudest aircraft ever produced, and its warmup could be heard 25 miles away. The test program was plagued by difficulties with control and engine reliability, and the XF-84H was cancelled in 1956 after the construction of two prototypes.

July 22, 1918 – The death of Indra Lal Roy, India’s only WWI flying ace. Born on December 2, 1898 in Calcutta, British India, Roy was attending school in London when the war broke out, and he was initially rejected by the Royal Flying Corps for poor eyesight. Only after getting a second opinion was he accepted for flight duty. After recovering from injuries suffered in the crash of his Royal Aircraft Factory S.E.5a, Roy returned to service and scored 13 victories (two shared) in just two days. Roy was killed in a dog fight against a Fokker D.VII, and was posthumously awarded the United Kingdom’s Distinguished Flying Cross, the first Indian to receive the honor. Roy was just 19 years old.

July 23, 2012 – The death of Sally Ride, a physicist, astronaut, and the first American woman in space. Born in Los Angeles, California on May 26, 1951, Ride joined NASA in 1978 and first went to space in 1983 as a Mission Specialist on board Space Shuttle Challenger on mission STS-7. With that flight, Ride became not only the first American woman in space and the first known LGBT astronaut, but, at age 32, she was also the youngest American astronaut to fly in space. Ride went to space a second time the following year, again on Challenger, as a Mission Specialist on ST-41-G. Ride left NASA in 1987, but served on the investigation committees into the Challenger and Columbia disasters. After teaching physics at the University of California, San Diego, Ride died of pancreatic cancer at age 61.

July 23, 1973 – The death of Eddie Rickenbacker. Born on October 8, 1890 in Columbus, Ohio, Rickenbacker was America’s leading ace in WWI and a recipient of the Congressional Medal of Honor. Rickenbacker served in the 94th Aero Squadron, nicknamed the “Hat-in-the-Ring” squadron, where he flew French-made Nieuport 28 and SPAD S.XIII fighters and finished the war with 26 confirmed victories. Rickenbacker eventually commanded the 94th then started the short-lived Rickenbacker Motor Company in 1920. Rickenbacker made his greatest contribution to aviation as the head of Eastern Air Lines, which he led from 1938 until his retirement in 1963. Rickenbacker died of a stroke at the age of 82.

July 23, 1952 – The first flight of the Fouga CM.170 Magister, a jet-powered trainer built for the French Armée de l’Air to replace the Morane-Saulnier MS.475. The world’s first purpose-built jet trainer to enter production, the Magister is a straight-wing monoplane with a distinctive V-shaped tail, a design element that Fouga borrowed from its CM.8 glider. Fouga also produced a naval variant for the French Navy, the CM.175 Zéphyr, which was used as the primary trainer for pilots learning carrier operations. The Magister also operated as a light attack aircraft, and could be armed with two machine guns and up to 310 pounds of external ordnance. Widely exported and also built under license by West Germany, Finland and Israel, a total of 929 CM.170s were produced.

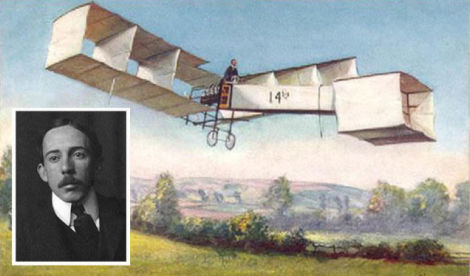

July 23, 1932 – The death of Alberto Santos-Dumont, a Brazilian aviation pioneer and one of the early inventors of aircraft in France. Born on July 20, 1873, Santos-Dumont got his start in aviation with ballooning and dirigibles, then constructed his first aircraft, the 14-bis, in which he made the first heavier-than-air flight in Europe in 1906. His final aircraft, the Demoisellemonoplane, became the world’s first production airplane. A national hero in his homeland, where he is considered the “father of flight,” Santos-Dumont committed suicide by hanging himself. He was said to be depressed over his multiple sclerosis, and also upset over the use of aircraft as a weapon of war in São Paolo’s Constitutionalist Revolution. Santos-Dumont was 59 years old.

July 23, 1930 – The death of Glenn Curtiss. Though often eclipsed in history books by the Wright Brothers, Glenn Curtiss was one of America’s greatest aviation pioneers, and has been credited with the creation of the American aviation industry. Born on May 21, 1878 in Hammondsport, New York, Curtiss’ credits include the first officially witnessed flight in North America, victory at the world’s first international air meet in France, and the first long-distance flight in the US. Curtiss also provided the US Navy with its first aircraft in 1911, the A-1 Triad, heralding the birth of US Naval Aviation. The Curtiss Airplane and Motor Company, and later Curtiss-Wright, made contributions to military aviation in both World Wars which are too numerous to mention here, but some of the most important aircraft built by him or his company include the JN4 “Jenny” biplane, the P-36 Hawk and P-40 Warhawk, the C-46 Commando, and the SB2C Helldiver.

Connecting Flights

If you enjoy these Aviation History posts, please let me know in the comments. And if you missed any of the past articles, you can find them all at Planelopnik History. You can also find more stories about aviation, aviators and airplane oddities at Wingspan.