Welcome to This Date in Aviation History, getting of you caught up on milestones, important historical events and people in aviation from July 27 through July 30.

July 27, 1949 – The first flight of the de Havilland Comet. Though we tend to think of the jet engine as a product of WWII, work had begun on the development of the turbojet engine as early as 1921. The first patent for an axial flow turbojet was granted to Frenchman Maxime Guillaume, though the engine was never built. Work progressed through the 1930s and 1940s, and both Britain and Germany fielded jet-powered fighters by the end of the war. The next logical step was to take the power of the jet engine and apply it to a large passenger airliner.

During the war, the British and Americans decided to split up the development of large, multi-engine aircraft, with the Americans assuming responsibility for transport aircraft, while the British focused on production of heavy bombers. However, that arrangement left the British in the unenviable position of having very little infrastructure or expertise for the production of transport aircraft when the war ended, and many British airliners were simply converted bombers. To address this shortcoming, the British formed the Brabazon Committee in 1942 under the direction of John Moore-Brabazon, 1st Baron Brabazon of Tara, which was tasked with the development of large, pressurized aircraft that could carry mail and passengers across the Atlantic Ocean. The committee began meeting in early 1943 and, over the next two years, they found that the requirements of the civilian aviation industry called for five different types of aircraft. One of the aircraft, designated the Type IV, would be a 100-seat, jet-powered, pressurized transatlantic mailplane that could carry one long ton of cargo at a cruising speed of 400 mph nonstop across the Atlantic.

A proposal for such an aircraft was put forward by Sir Geoffrey de Havilland, who headed his own aircraft company and had influential government ties. If successful, the new airliner would fill the need for the Type IV aircraft, as well as Type III, a short-range airliner capable of serving multi-hop routes around the British Empire. A contract was awarded to develop the de Havilland Type 106, which later became known as the DH 106, and de Havilland undertook the design of both the airframe and the engines. While initial studies into the design of the Comet included proposals for a radical tailless design, de Havilland eventually settled on a traditional configuration with a straight wing that had a leading edge swept at 20 degrees and a straight tailplane. The engines were housed in the wing roots, and the groundbreaking airliner featured large, square windows for the passengers. The prototype was powered by four de Havilland Ghost turbojet engines, but those were replaced by more powerful Rolls-Royce Avon axial flow jet engines in production models.

After rigorous testing, the first Comet prototype took its maiden flight on July 27, 1949, and the airliner was introduced to the world at the Farnborough Airshow later that year. The Comet entered service with British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC) on May 2, 1952 and was an immediate success, attracting high-profile passengers including the Queen Mother. However, structural weaknesses around the large windows soon caused a number of fatal in-flight explosive decompressions, and the Comet was pulled from service in 1954 to investigate the cause of the hull losses. The failures were traced to fatigue cracks around the large windows that arose from repeated pressurization and depressurization of the fuselage, so new rounded windows were introduced, along with a strengthened hull. Comets returned to the skies in 1958 and, though the accidents hurt sales, the airliner went on to enjoy a long career, even after it was surpassed by more modern airliners like the Boeing 707. Continued development of the Comet led to the creation of variants that stretched the airliner and added more seats and more fuel for increased range. And, when it looked like the Comet’s flying days were over, it was further developed into the Hawker Siddeley Nimrod maritime patrol and surveillance aircraft. Including the prototypes, a total of 114 Comets were produced, and the last was retired in 1997.

July 28, 1935 – The first flight of the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress. In the lead up to the Second World War, two schools of thought emerged on how bombers could be used in battle. The first, tactical bombing, was developed to support ground forces in the achievement of a specific objective, such as overcoming a fortified position or destroying a bridge, while the second, strategic bombing, would be carried out by waves of bombers flying over enemy territory in an effort to destroy factories or flatten cities in hopes of destroying the morale of the civilian population. The Germans focused on the former, and honed the combined arms tactics into the Blitzkrieg warfare that was so effective early in the war. England and America, however, adopted the strategic theories of bombing, particularly those of Italian Giulio Douhet. Proponents such as Hugh Trenchard in England and Billy Mitchell in America advocated the construction of fleets of heavy bombers based on the belief that “the bomber will always get through.”

During the 1930s, rapid advances in aircraft design and construction left behind the fabric-covered biplanes of the 1920s in favor of all-metal monoplanes of increasing size, strength and capability. Boeing introduced the US Army Air Corps’ first all-metal bomber with the YB-9 in 1931, and Martin followed in 1934 with the B-10, the first truly modern bomber. But as soon as the B-10 entered service, the USAAC began the search for a new bomber to replace it, one that would be capable of carrying a “useful bomb load” at 10,000 feet, could stay aloft for 10 hours, and have a speed of 200 mph. A competition took place at Wright Field in Ohio between the Douglas B-18 Bolo, the Martin Model 146, both twin-engine aircraft, and the Boeing Model 299, which had four engines. When the new Boeing bomber, bristling with defensive armament, was first rolled out to the press, a newspaper reporter remarked that the bomber looked like a “flying fortress.” The name stuck.

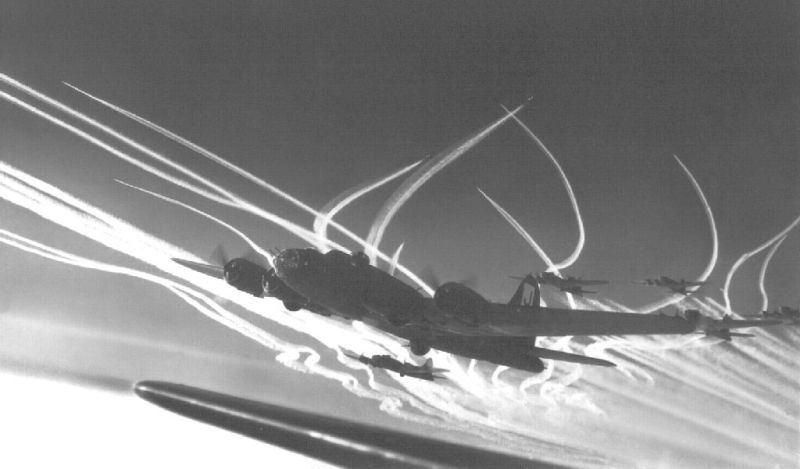

While USAAC brass were impressed by the performance of the Model 299, now carrying the designation YB-17, they were concerned about the higher cost of the larger bomber. Following the a crash during testing that destroyed the Boeing prototype, the Air Corps chose the Martin bomber. But this was not the end of the B-17. Its performance was impressive enough for the USAAC to order 13 YB-17s for further evaluation, and its performance in testing was so good that by the outbreak of WWII in December of 1941 there were already 155 Flying Fortresses in the air. As the Flying Fortress showed its mettle in combat, those numbers soon soared into the thousands. Following the B-17's first foray into battle in the hands of British pilots, the 8th Air Force alone racked up more than 10,000 missions over Europe. The B-17G variant, which was built in the greatest numbers (over 8,000), had no less than 13 defensive M2 Browning .50 caliber machine guns and could carry up to 8,000 pounds of bombs depending on the mission. To meet the demand, wartime production of the B-17 was carried out by Boeing, Douglas, and Vega (a subsidiary of Lockheed), and a staggering total of 12,731 Flying Fortresses were produced by the end of the war.

While the bomber didn’t always get through, the Flying Fortress was capable of withstanding an enormous amount of damage while still bringing its crew home. The B-17 became the iconic American bomber of the war in Europe, and teamed up with the Consolidated B-24 Liberator and other smaller bombers to rain 1.4 million tons of bombs on Axis targets, with the B-17 accounting for roughly half that number. As for strategic bombing, postwar analysis discovered mixed results. While Germany’s production of oil and ammunition was significantly affected, along with the almost total destruction of transportation capabilities and the halt of submarine production, supplies of aircraft actually increased throughout the war, and other supplies, such as ball bearings and steel, were virtually unaffected. Anywhere from 350,000 to 500,000 civilians were killed, but bombing itself did not lead directly to German capitulation. Following the war, the vast majority of B-17s were broken up and sold for scrap, though a handful continued to serve in different roles. The Brazilian Air Force retired its last Flying Fortress in 1968, and today only about 14 remain airworthy, none of which are combat veterans.

July 29, 1967 – Fire engulfs the flight deck of USS Forrestal off the coast of Vietnam. Working on the flight deck of an aircraft carrier has been called one of the most dangerous jobs in the world. Controlling jet and propeller aircraft around a pitching deck is an intricate ballet of blasting jet engines and spinning propellers, with death or serious injury a constant concern. And that is just during peacetime. In wartime, the dangers are compounded by a higher tempo of operations and the presence of bombs, missiles, rockets and fully-fueled aircraft either on the flight deck or stored belowdecks. In fact, the Battle of Midway took a critical turn when American dive bombers arrived overhead while Japanese aircraft were sitting on deck, fully loaded with bombs and fuel. The US Navy has been honing the art of carrier operations and carrier safety since 1920, but despite rigid safety procedures, there is always the potential for disaster.

By the early summer of 1967, the war in Vietnam was escalating dramatically, and the carrier USS Forrestal (CVA-59) sailed from Norfolk, Virginia to take up a position at Yankee Station in the Gulf of Tonkin off the coast of Vietnam. Once there, Forrestal immediately began launching attacks against North Vietnam in support of American and South Vietnamese troops and, as the pace of operations increased, the Navy’s demand for bombs soon outstripped production. To keep the bombers flying, the Navy was forced to use older ordnance, some of which dated back more than 10 years and had been exposed to the elements while in storage. On the day preceding the accident, Forrestal received a shipment of 1000-pound bombs, many of which were older, unstable bombs that had been improperly stored in Guam. Forrestal’s commanding officer, Captain John Beling, at first refused the munitions, but he ended up accepting them reluctantly because of the acute shortage and the need for the bombs on missions the following day. Forrestal’s bomb handlers were particularly concerned with the unstable bombs being stored belowdecks, where an accidental explosion could sink the entire ship. So the bombs were stored out in the open on the flight deck.

The next day, the deck of Forrestal was crammed with fueled and armed aircraft and swarmed with deck handlers, pilots, and other personnel. Shortly before 11:00 am an electrical fault in a 5-inch Zuni rocket caused it to launch unintentionally from a McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom parked on the flight deck and strike the external fuel tank on an armed Douglas A-4 Skyhawk. While the rocket did not explode, it punctured the fuel tank and the leaking fuel ignited. As damage control teams rushed to fight the rapidly spreading fire, one of the unstable bombs loaded on the Skyhawk detonated, blowing a hole in the armored flight deck and raking the deck with shrapnel. Most of the members of Forrestal’s most experienced damage control team were killed, and even more burning fuel was spread around the deck. As the fires continued to rage, nine more explosions occurred, eight of which were caused by the unstable bombs. The detonations tore holes in the flight deck that allowed burning jet fuel to flow into the living quarters below and into the interior spaces of the ship. Without heavy equipment, Forrestal’s crew pushed damaged aircraft into the water and rolled bombs over the side of the ship by hand.

In what Rear Admiral Harvey P. Lanham later called an act of “magnificent seamanship, ” Commander Edwin Burke maneuvered the destroyer USS Rupertus (DD-851) to within 20 feet of Forrestal and held station there for 90 minutes in order to use its own fire hoses to fight the fire, and Forrestal’s crew was eventually able to extinguish the fire by 4:00 am the following morning. The fire and explosions, the worst on a US carrier since WWII, claimed the life of 134 crewmen, while 161 were injured, many of them seriously. Forrestal returned to Norfolk, where it spent more than 200 days undergoing repairs and refitting. Though Capt. Beling was absolved of responsibility for the fire, he was assigned to staff work following the incident and retired in 1973 with the rank of Rear Admiral. Forrestal returned to service in the Mediterranean in 1968, and was decommissioned in 1993.

July 30, 1959 – The first flight of the Northrop F-5A Freedom Fighter. When the first jet fighters appeared near the end of WWII, they were relatively simple affairs, essentially straight-winged piston aircraft that were adapted for the new turbojet engines. But as jet engines became more powerful, fighters got bigger, more complex—and more expensive. To combat this trend, Northrop began working on a small, simple fighter in the mid-1950s called the N-156 in the hopes of securing a contract to produce a fighter that could fly from the US Navy’s smaller escort carriers. The design team was led by Northrop’s vice president of engineering Edgar Schmued, who designed two of arguably the greatest fighters ever built, the North American P-51 Mustang and North American F-86 Sabre, before coming to Northrop. Along with chief engineer Welko Gasich, the Northrop team set out with the specific goal of creating a small, low-cost fighter that would be easy to maintain and easy to fly, but would also have the potential for future growth and development.

Not only were fighters getting larger and larger, but the engines that powered them were also growing in size and complexity. To keep the size of their new fighter at a minimum, Northrop selected two powerful General Electric J85 turbojet engines which had originally been designed to power the McDonnell ADM-20 Quail target decoy. Though the J85 was small, weighing in at just 300-500 pounds, it provided 3,500 pounds of thrust in normal operation and 5,000 pounds with afterburner. Combined with the fighter’s small size and use of the area rule, which gave the F-5 its characteristic slim waist, the F-5 was capable of a top speed of Mach 1.6 with a thrust-to-weight ratio of up to 7.5:1, compared to the McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom at just 4.7:1. The F-5 was armed with two 20mm M39A2 revolver cannons in the nose with 280 rounds each. Seven hardpoints could carry up to 7,000 pounds of bombs, rockets, missiles, or extra fuel tanks.

The changing needs of the US Navy led them to abandon the use of smaller escort carriers, but Northrop forged ahead with their design and developed both a single-seat fighter version, the N-156F, and a two-seat trainer version, the N-156T. In July 1956, the Air Force chose the N-156T to replace the Lockheed T-33 Shooting Star as its primary trainer, and the newly designated T-38 Talon became both the first supersonic trainer and eventually the most-produced trainer in the world. Northrop continued developing the N-156F in the hopes of providing a fighter for the Military Assistance Program, which sought to arm nations allied to the US with low-cost weapons. It was this aircraft which took its maiden flight on July 30, breaking the sound barrier on its first flight. Despite the excellent performance and reliability of the F-5, the Air Force showed little interest in the fighter, and the program was in danger of being shut down. However, the Kennedy Administration chose the F-5 in 1962 as the winner of the F-X completion to provide a low-cost export fighter to America’s allies. In 1965, the Air Force sent 12 F-5As to Vietnam to evaluate them under the codename Project Skoshi Tiger, and it was here that the F-5 received its unofficial nickname, which later became official with the F-5E/F Tiger II.

While the F-5A and F-5E/F weren’t adopted in large numbers by the US, it continues to be flown in the aggressor role for dissimilar combat training, and the Air Force has also bought back some export fighters for use in this role. The Tiger II, which won the International Fighter Aircraft competition in 1970, remains in service alongside older Freedom Fighters the world over. Northrop attempted yet another upgrade to the plucky little fighter with the F-20 Tigershark, hoping to develop an export fighter that would compete with the General Dynamics F-16 Fighting Falcon, but it was ultimately unsuccessful. By the end of production in 1987, a total of 847 F-5A/B/C aircraft had been built, along with nearly 1,400 F-5E/Fs.

Short Takeoff

July 27, 1958 – The death of Claire Chennault. Chennault was born September 6, 1890 in Commerce, Texas and became a pilot during WWI after a stint as a school principal. A proponent of the pursuit fighter in the 1930s at a time when the US Army was focused on bombers, Chennault left the Army in 1937 and worked as an aviation advisor to the Chinese government, becoming the head of the 1st American Volunteer Group, better known as the Flying Tigers, in 1941. Chennault led the AVG and, later, the US Army Air Forces units that followed the disbandment of the AVG, but openly feuded with General Joseph Stilwell, the US Army commander in China. Stilwell wanted Chennault’s forces to support ground supply routes into China, while Chennault advocated bombing Japanese targets in support of Chinese Nationalist forces. Following the war, Chennault created the Civil Air Transport, later known as Air America, to support the Nationalist fight against Communist China. Chennault died in 1958 at age 64.

July 27, 1947 – The first flight of the Bristol Sycamore, the first domestically designed and built helicopter to serve with the Royal Air Force. Bristol began working on helicopters as early as 1944, and development of the Sycamore took over two years. The prototype was powered by a Pratt & Whitney Wasp Junior 9-cylinder radial engine, though production models were fitted with an Alvis Leonides radial engine which provided a top speed of 132 mph. The Sycamore entered service in April 1953 and served during the Malayan Emergency, and was also flown by Germany, Belgium and Australia. A total of 180 were built from 1947-1955, and the type was retired in 1972.

July 27, 1946 – The first flight of the Supermarine Attacker, a fighter developed for the Royal Navy’s Fleet Air Arm (FAA) and the first jet fighter to enter operational service with the FAA. The Attacker has its roots in the Supermarine Spiteful, a piston-powered fighter designed to replace the Supermarine Spitfire. The Attacker used the same straight, laminar flow wings of the Spiteful and was powered by a single Rolls-Royce Nene turbojet which gave it a top speed of 590 mph. Since the wings, with their main landing gear, came from an existing fighter, the Attacker had a tail-dragger arrangement which was unusual for a jet fighter. The Attacker entered service with the FAA in 1951, but developments in jet fighter design quickly rendered it obsolete, and it was withdrawn from service in 1954 after the production of 182 aircraft.

July 27, 1937 – The first flight of the Focke-Wulf Fw 200 Condor, a large four-engine aircraft originally developed by Focke-Wulf as a long-range transatlantic airliner. Focke-Wulf’s chief designer Kurt Tank developed the Condor to cruise at nearly 10,000 feet, the limit for an unpressurized airliner. The Condor enjoyed a brief career as an airliner with Deutsche Lufthansa, where it set a record for flying from Berlin to New York City in just under 25 hours. With the outbreak of WWII, Focke-Wulf added a gondola and bomb bay to turn the Condor into a long-range maritime patrol bomber. Later, the Condor was used exclusively by the Luftwaffe as a troop and VIP transport. A total of 276 were produced from 1937-1944.

July 28, 2008 – The death of Margaret Ringenberg. Born in Fort Wayne, Indiana on June 17, 1921, Ringenberg learned to fly in 1941 at age 19 and began her flying career in 1943 as part of the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP), ferrying aircraft, performing test flights, and pulling targets for fighter practice. After the war, Ringenberg took up air racing, eventually earned over 150 trophies, and competed in the Round-the-World Air Race in 1994 at the age of 72. At the time of her death, Ringenberg had amassed more than 40,000 hours of flying time.

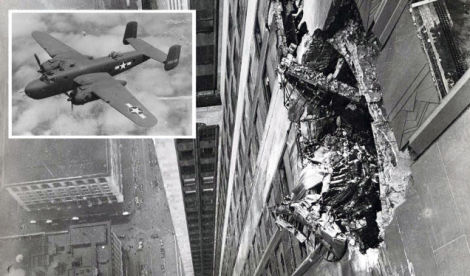

July 28, 1945 – A North American B-25 Mitchell crashes into the Empire State Building. During a period of thick fog over New York City, a US Army Air Forces B-25 was performing a routine personnel transport mission when the pilot was instructed to abort his landing and proceed to Newark Airport due to poor visibility. Becoming disoriented in the fog, pilot William Smith crashed into the Empire State Building between the 78th and 80th floors, killing himself, his two passengers, and 11 civilians inside the skyscraper. Based on this accident, the architects of the World Trade Center considered the possibility of an accidental impact by a Boeing 707 when they designed the towers, little knowing that such a scenario would play out purposefully in 2001.

July 28, 1914 – World War I begins. World War I was a watershed event in the history of aviation, as the airplane became a weapon of war a mere 11 years after the first flight of the Wright brothers. Aircraft first entered the fray as observation planes known as scouts, but pilots soon began shooting at each other with small arms. The first dedicated combat aircraft, the Vickers F.B.5, arrived in early 1915. Technological advances brought ever more powerful and faster fighters, and an interrupter mechanism created by Anthony Fokker allowed fighters to fire through the arc of the propeller, thereby dramatically increasing the accuracy and effectiveness of aerial marksmanship. By the end of the war on November 11, 1918, the Germans has lost more than 27,000 aircraft to enemy fire or crashes, while members of the Entente powers lost more than 88,000. More than 15,000 airmen were lost.

July 29, 1958 – President Dwight Eisenhower signs the National Aeronautics and Space Act, creating NASA. NASA has its origin in the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, an agency created in 1915 to further the efforts of aeronautic research and technological development in the United States. But as America entered the space age following WWII, the country needed an organization for a new era. The National Aeronautics and Space Act carries this simple preamble: To provide for research into problems of flight within and outside the earth’s atmosphere, and for other purposes. While NASA has done, and continues to do, research that carries military implications, its stated purpose is that of a peaceful, non-military organization. The Act goes on to say that, “The Congress hereby declares that it is the policy of the United States that activities in space should be devoted to peaceful purposes for the benefit of all mankind.” In addition to NASA’s high profile space programs such as Mercury, Gemini, Apollo, the Space Shuttle, and the International Space Station, the organization continues to fund research into all aspects of space exploration, space travel, aviation, and related sciences. NASA’s latest large project, the Space Launch System and the Orion Multi-Purpose Crew Vehicle, will see astronauts return to the Moon, create a permanent lunar station, and one day journey to Mars.

July 29, 1952 – A US Air Force North American RB-45 Tornado completes the first non-stop jet-powered flight across the Pacific Ocean. The B-45 has the distinction of being the first jet-powered bomber to enter US Air Force service, and though it was quickly superseded by the Boeing B-47 Stratojet, the RB-45 reconnaissance variant served until 1959 and made flights over the Soviet Union. To demonstrate the capability of the bomber, a B-45 of the 91st Reconnaissance Wing commanded by Maj. Lou Carrington departed from Alaska and arrived in Japan 9 hours and 50 minutes later, refueling twice in the air along the way. The midair refueling by Air Force KB-29 tankers also marked the first time a multiengine jet bomber was refueled in flight. Carrington and his crew were awarded the MacKay Trophy by the Air Force in recognition of the “most meritorious flight of the year.”

July 30, 1971 – The Apollo 15 mission deploys the first Lunar Rover on the Moon. Apollo 15 was the ninth manned mission launched by NASA as part of the Apollo program, and the fourth to land on the Moon. It was also the first of the so-called J missions which featured extended stays of more than three days on the lunar surface and a greater emphasis on scientific exploration. In order to cover more ground than was possible on foot, Apollo 15 deployed the first Lunar Roving Vehicle (LRV), a battery-powered rover that could carry two astronauts at speeds of six to eight mph. Over the course of their stay on the Moon, astronauts David Scott and James Irwin covered a total distance of 17.25 miles in the Rover. The Rover, along with ones deployed by Apollo 16 and Apollo 17, remain on the Moon.

July 30, 1958 – The first flight of the de Havilland Canada DHC-4 Caribou, a cargo aircraft designed for short takeoff and landing (STOL) to fulfill a requirement from the US Army for a tactical airlifter to supply frontline troops. Following the DHC Beaver and DHC Otter, the Caribou was the first aircraft designed by de Havilland Canada to have two engines, and it entered US Army service in 1961 where it was known as the C-7. Initially seeing service in Vietnam, the Caribou’s ability to operate from runways as short as 1,200 feet made it an ideal complement to the Air Force’s larger cargo airplanes. A total of 307 were produced, and the final Caribous were retired from military service by the Royal Australian Air Force in 2009.

July 30, 1954 – The first flight of the Grumman F-11 Tiger, a day fighter developed by Grumman for the US Navy that began as an advanced development of the Grumman F-9 Cougar. Grumman eliminated the wing root air intakes and moved them forward to help reduce drag, made the wing thinner, moved the elevator down to the fuselage, and reshaped the fuselage to take advantage of the newly discovered principle of area rule. The Tiger remained a work in progress throughout its career, and also earned the dubious distinction of being the first jet to shoot itself down when it overtook its own bullets in a dive during weapons testing. The Tiger’s operational career was relatively short, though it gained notoriety when the fighter was selected by the Navy’s Blue Angels in 1957. A total of 200 Tigers were produced from 1954-1959, and it was retired from active service in 1961, though it served the Blue Angels until 1969.

Connecting Flights

If you enjoy these Aviation History posts, please let me know in the comments. And if you missed any of the past articles, you can find them all at Planelopnik History. You can also find more stories about aviation, aviators and airplane oddities at Wingspan.