Welcome to This Date in Aviation History, getting of you caught up on milestones, important historical events and people in aviation from September 4 through September 6.

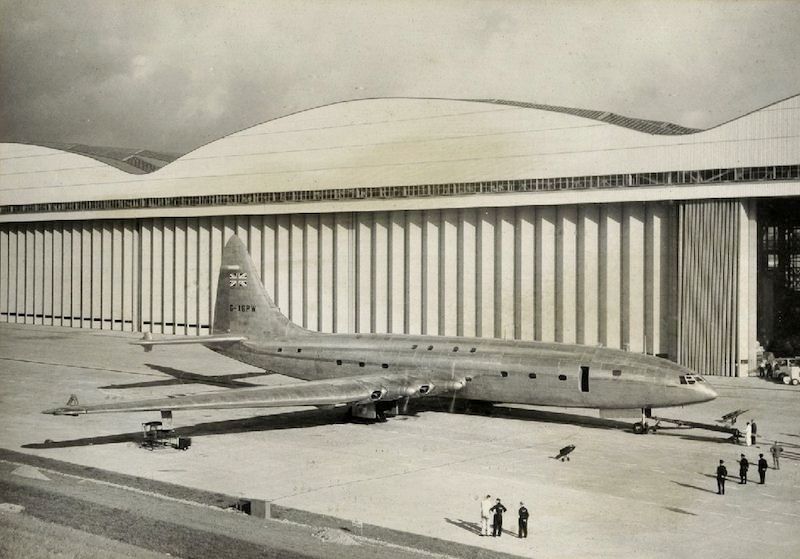

September 4, 1949 – The first flight of the Bristol Brabazon. History tends to remember the great planes, the ones that broke records, helped win wars, or made the world a smaller place. But oftentimes, aircraft that failed to enter widespread production are as fascinating as those that do. Planes like the Hughes H-4 Hercules, better known as the Spruce Goose, may not have been commercially viable, but their story is one that is worth telling, an example of thinking on a grand scale that was every bit as impressive as it was impractical.

During WWII, the British government entered into an agreement with the United States whereby England would focus their efforts on the development of bombers and other military aircraft while the US provided them with transport aircraft. By the middle of the war, and looking to the future, the British government faced the unfortunate situation of having no significant transport aircraft under development to fly passengers after the war. In fact, many of the first postwar British airliners were converted bombers such as the Avro Lancastrian, which was developed from the Avro Lancaster strategic bomber.

In 1943, the Brabazon Committee, led by John Moore-Brabazon, 1st Baron Brabazon of Tara, was assembled to address the vacuum in British aircraft design left by the absence of passenger aircraft development. The committee set to work identifying and categorizing England’s postwar aviation needs, and the report filed by the committee settled on four different aircraft types that would feature different levels of range, capacity and propulsion. Type I called for a large, transatlantic airliner intended to serve the routes between London and New York, a 12-hour flight at the time. Bristol had already been working on what was called a “100 ton bomber,” one that found its closest parallel in the American Consolidated B-36 Peacemaker. However, development was halted when such a large bomber was deemed unnecessary. So when the call came for a large airliner, Bristol returned to the huge bomber and instead developed it into the Brabazon.

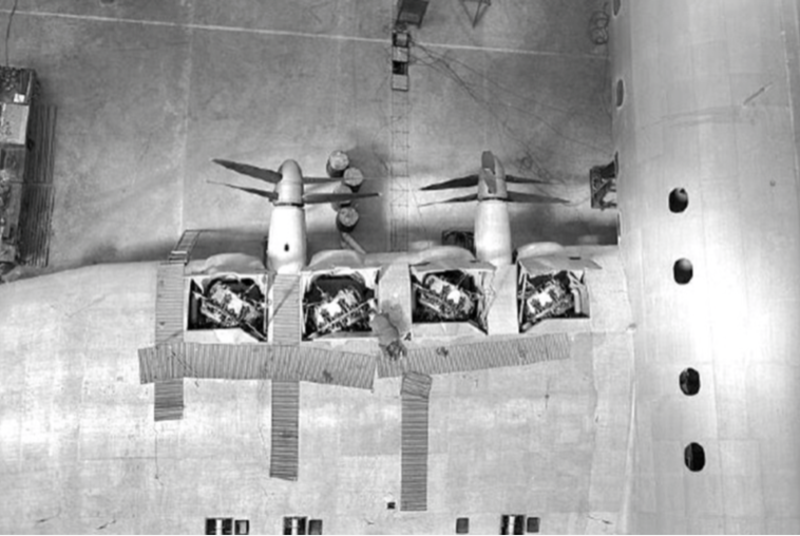

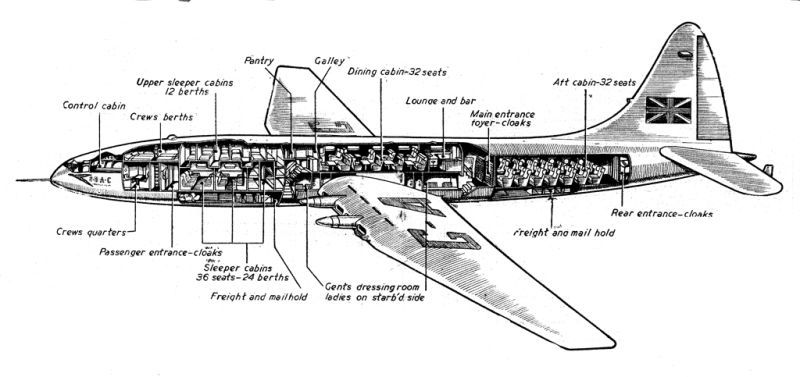

To pull such a large aircraft through the sky, the Brabazon featured four sets of contra-rotating propellers, but where many aircraft of this design used one engine to turn both propellers, the Brabazon used two, one for each prop. The Brabazon was powered by a total of eight Bristol Centaurus 18-cylinder engines, each providing over 3,000 horsepower to one prop. Cruising speed was 250 mph, with a range of 5,500 miles flying at 25,000 feet. The Brabazon was an enormous aircraft, almost as large as a modern Boeing 767, and its size would lead one to believe it could carry hundreds of passengers. However, the Brabazon only accommodated 100 passengers. Instead of row upon row of seats, it had sleeping berths, a galley, a 32-seat dining cabin and a lounge with a bar. Bristol hoped that such an arrangement would appeal to big money travelers who could afford such accommodations. But carrying so few passengers in such grand style hearkened back more to transcontinental train travel than transatlantic passenger flight, and the arrangement was not appropriate for the burgeoning passenger market, where making money meant carrying as many passengers as possible.

One protoype was constructed, but the airlines had no stomach for such a large, expensive airplane that carried so few passengers. After millions of pounds were spent in development, the Brabazon was canceled in 1953. Though the Brabazon itself was deemed a failure, Bristol benefited from what it learned building the huge airliner, knowledge that they put to use developing the more traditional (and more successful) Bristol Britannia. And the British aviation industry as a whole benefited from the increase in manufacturing infrastructure and techonological development that went along with the Brabazon and the rest of the work of the Brabazon Committee. Following its cancellation, the single Brabazon was broken up for scrap in 1953, along with the second uncompleted prototype, which would have been powered by turboprop engines. The Brabazon, despite its size, was relegated to relative obscurity.

Short Takeoff

September 4, 1957 – The first flight of the Lockheed JetStar, the first dedicated business jet to enter service and, with accommodations for up to ten passengers, the largest in its class at the time. Unlike most bizjets of the era, the JetStar had four engines rather than two, and was originally powered by four Pratt & Whitney JT12 turbojets. Later production aircraft received quieter, more fuel-efficient Garrett TFE731 turbofan engines that gave it a top speed of 547 mph. Not only did it serve as Kelly Johnson’s personal jet, the JetStar entered US military service as the C-140 and also served as President Lyndon Johnson’s personal aircraft, which he nicknamed Air Force One-Half. Just over 200 were produced from 1957-1978.

September 4, 1936 – Louise Thaden becomes the first woman to win the prestigious coast-to-coast Bendix Trophy Race. At a time when aviation was dominated by male pilots, Louise Thaden shocked the world when she and her copilot Blanche Noyes won the Bendix transcontinental race. The pair set a new world record time of 14 hours 55 minutes flying a Beech C17R Staggerwing. But that was only the first of Thaden’s accomplishments. She set a altitude record of 20,260 feet for woman pilots in 1928, an endurance record of over 22 hours in 1929, teamed up aviatrix Frances Marsalis to set a record time of 196 hours in the air, and was a founding member of the Ninety-Nines organization for woman pilots. Though she retired from racing in 1938, Thaden served with the Civil Air Patrol during WWII, and died in 1979.

September 4, 1933 – The death of Florence Gunderson Klingensmith, an American aviatrix active during the Golden Age of Aviation and one of the first to participate in air races against male pilots. Klingensmith became interested in aviation after Charles Lindbergh visited her hometown of Fargo, North Dakota, and she began her flying career as a performing skydiver in exchange for flying lessons. She acquired her first airplane by going door to door to solicit funds, and she set a world record in 1931 by completing 1,078 loops in succession. Taking up air racing, Klingensmith was the first woman to enter the Frank Phillips Trophy Race in 1933 flying a Gee Bee Model Y Senior Sportster. While flying in fourth place at over 200 mph, the airplane began to disintegrate, and Klingensmith was killed while attempting to bail out. Her death led to a ban on women participating in air races. Klingensmith was 29 years old.

September 5, 1936 – Beryl Markham completes the first solo westward crossing of the Atlantic Ocean by a woman pilot. Born in England, Markham became one of the first African bush pilots and flew as a game spotter for hunters on safari. Her transatlantic crossing began on September 4 and was planned from Dublin to New York City. However, poor weather forced her down in New Brunswick, Canada. Still, she completed the crossing, which is more difficult than going eastward since the pilot has to fly against the prevailing winds. Markham’s memoir West with the Night chronicles this flight, as well as other flying adventures she undertook. Markham died in 1986 at age 83.

September 5, 1982 – The death of Douglas Bader, a WWII RAF fighter ace credited with 22 confirmed victories, four shared victories, and 11 damaged enemy aircraft. Bader had lost both legs, one above and one below the knee, in an aerobatic crash in 1931, but after his recovery he rejoined the RAF at the start of WWII. Bader scored victories in the skies over Dunkirk and later took part in the Battle of Britain. In August of 1941, he bailed out of his stricken fighter over France and was captured. However, despite his disability, Bader made so many escape attempts that his jailers threatened to confiscate his prosthetic legs. He was then held at Colditz Castle, where he remained imprisoned until the end of the war. Following the war, Bader continued flying until poor health forced him to quit in 1979. For his war service, Bader was awarded the Order of the British Empire, the Distinguished Service Order and Distinguished Flying Cross.

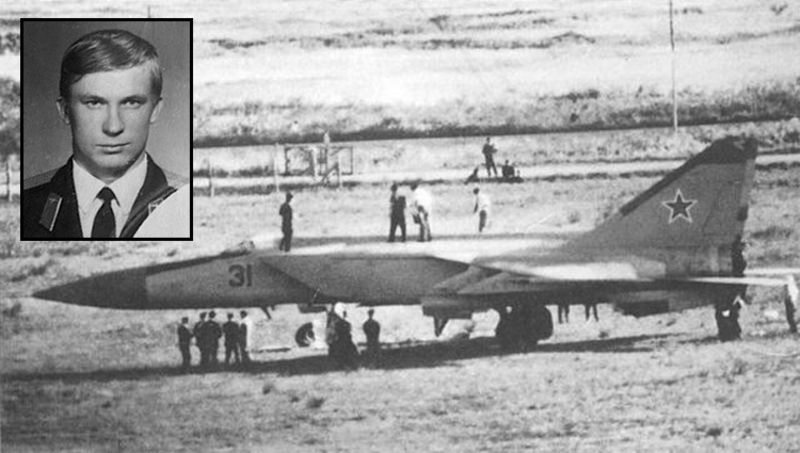

September 6, 1976 – Russian fighter pilot Viktor Belenko flies his MiG-25 Foxbat to Japan and defects to the West. Around 1970, Western spy satellites took their first images of a very large Soviet aircraft which analysts believed to be a new, highly maneuverable fighter. With spotty reports of an incredibly fast aircraft sighted near Israel, the US ramped up development of the McDonnell Douglas F-15 Eagle in response to the perceived threat. But the Soviet fighter remained shrouded in mystery until Lieutenant Viktor Belenko landed his factory-fresh MiG-25, complete with the flight manual, at Hakodate, Japan, and asked for asylum. The Japanese invited US technicians to inspect the fighter, NATO codename Foxbat, and the aircraft was completely disassembled. Fears over the aircraft were somewhat allayed when it was discovered that, while the Foxbat could approach speeds of Mach 3, it had a very short range, and was nowhere near as maneuverable as surmised, as it was intended as an interceptor rather than a fighter. The Foxbat was also very heavy, using mostly a nickel steel alloy rather than titanium. The MiG-25 was eventually returned to the Soviets in 30 crates, and the aircraft was subsequently reassembled and placed on display at the Sokol plant in Nizhny Novgorod.

Connecting Flights

If you enjoy these Aviation History posts, please let me know in the comments. And if you missed any of the past articles, you can find them all at Planelopnik History. You can also find more stories about aviation, aviators and airplane oddities at Wingspan.