Welcome to This Date in Aviation History, getting of you caught up on milestones, important historical events and people in aviation from September 14 through September 17.

September 14, 1939 – The first flight of the Sikorsky VS-300. While the helicopter as we know it is a relatively modern invention, the idea for vertical flight goes all the way back to 400 BC, when Chinese children played with toys that had a wing on a stick that could be spun in their hands, toys that still exist today. The first known design for a vertical flying machine can be found in the works of the Renaissance artist and engineer Leonardo da Vinci, though it’s unlikely that his aerial screw design would have been capable of flight. While it’s possible that he created flying models, there was no provision for keeping the whole craft from spinning under the influence of the rotor. Aircraft designers continued to chase the dream of vertical flight, and it was actually achieved in aircraft such as the Focke-Achgelis Fa 223, though that aircraft had two rotors on twin booms to counteract the torque from the spinning rotors and looked more like an airplane with rotors than a helicopter. Many others tried, but it was not until Russian emigre Igor Sikorsky developed his VS-300 that the dream of vertical flight with a single rotor became a practical reality.

Putting a large, spinning propeller on top of the helicopter was an obvious configuration, but the torque from that rotor would make the entire helicopter would spin along with it. Sikorsky experimented with numerous configurations before settling on the single, vertical tail rotor to control aircraft yaw, an arrangement that has become standard on most helicopters to this day. But perhaps his greatest breakthrough came with his development of a cyclic control that tilted the spinning rotor disc to impart motion in a desired direction. Other controls directed the tail rotor and regulated engine speed, and the system of controls that Sikorsky developed has become the standard control system on most helicopters to this day. In order to test his design safely, Sikorsky took a series of tethered flights, always flying the machine himself while wearing his trademark fedora.

Following refinements to the control system, the first untethered flight took place in May 1940. Where other designers had used multiple engines to power the main rotor and tail rotor of their helicopters, the VS-300 used a single 75 horsepower engine to turn both, becoming the first in the US to use a single lifting rotor and a single engine. Sikorsky later developed the VS-300 into the R-4, which was purchased by the US Army and became the world’s first mass produced helicopter.

September 15, 1991 – The first flight of the Boeing C-17 Globemaster III. Napoleon Bonaparte (or perhaps Frederick the Great) famously said, “An army marches on its stomach,” meaning that without food and supplies, an army goes nowhere and doesn’t fight. Practically the entire history of warfare has revolved around logistics—getting the army to the fight and getting the supplies to the army—no matter how far from home that fight is. By WWII, the development of large strategic airlifters made the task of supply significantly easier and, by the 1960s, the job was being done by large jet-powered aircraft like the Lockheed C-141 Starlifter and Lockheed C-5 Galaxy.

But as the US Air Force looked at the logistics problems of the 1970s, particularly after their experiences in the Vietnam War, they realized that they needed a cargo jet that could not only haul more goods farther but also land on shorter, rougher runways. To deal with these new challenges, the Air force created a set of requirements as part of its Advanced Medium STOL Transport program (AMST) and evaluated two entries: the Boeing YC-14 and the McDonnell Douglas YC-15. Both aircraft took design cues from the Lockheed C-130 Hercules, having a high wing to maximize cargo capacity and a raised tail to allow cargo loading in the rear. However, the AMST program was canceled before a winner was chosen, and it wasn’t until 1980, when the Air Force was facing the reality of a fleet of aging C-141s, that they revisited the concept, now designated the C-X program.

In response to these new requirements, McDonnell Douglas updated their earlier YC-15 design, Boeing brought an updated version of the YC-14, and Lockheed doubled down two proposals, one based on the C-5 and a second that was an enlarged version of the C-141. Ultimately, the Air Force chose McDonnell Douglas, and gave their aircraft the designation C-17 Globemaster III, a name which pays homage to two earlier airlifters that both carried the nickname, the Douglas C-74 and C-124. Delays in development and a shortage of funds almost led to the cancelation of the project once again, and caused the program to be delayed a further five years. Finally, in 1985, a development contract was awarded, with delivery slated to begin in 1990 (McDonnell Douglas had merged with Boeing in 1997, so the C-17 would carry the Boeing nameplate).

The C-17 is powered by four Pratt & Whitney F117 turbofan engines which give it a cruising speed of 515 mph and a range of up to 5,600 miles, depending on the cargo load. It can carry up to 170,900 pounds of cargo, which includes as many as 134 troops or one M1 Abrams main battle tank. The C-17 can also carry three M1126 Stryker infantry vehicles or six M1117 Guardian armored security vehicles. Thrust reversers that direct the jet exhaust upward give the C-17 a stopping distance of as little as 3,500 feet while reducing the dangers of ingesting foreign object debris into the engines. During testing, the C-17 set 33 world records, including a record for STOL capability in which a C-17 took off in less than 1,400 ft, carried a payload of 44,000 pounds to altitude, and then landed in less than 1,400 ft. In recognition of the C-17's ability, it was awarded the Collier Trophy for achievement in aeronautics. The first C-17s entered service in 1993, and a total of 279 were built before production ended in 2015. Globemaster IIIs remain in service with the US Air Force, the Royal Air Force, the Royal Australian Air Force and the Indian Air Force.

September 17, 1959 – The first powered flight of the North American X-15. The decades of the 1950s and 1960s were an extraordinary time in the history of aviation. Following the adoption of the turbojet engine late in WWII, designers raced to develop aircraft that could fly ever higher and faster, even to the edges of space, while seemingly bottomless Cold War defense budgets funded research into aviation. The burgeoning Space Race between the United States and the Soviet Union meant that money for research and development was always in good supply.

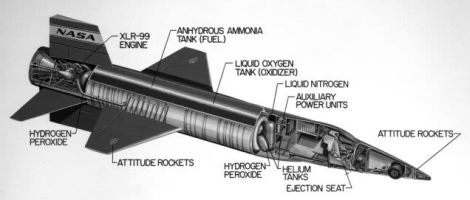

The X-15 was part of a long lineage of experimental aircraft, known collectively as the X planes. Beginning with the Bell X-1, which broke the sound barrier for the first time in 1947, these innovative and often revolutionary aircraft were developed to explore, test and evaluate cutting edge theories about aircraft design and propulsion, and push against the edges of the flight envelope, In 1952, the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA, the predecessor to NASA), began investigating the possibilities of space flight and, by 1954, the committee set forth guidelines for an aircraft that could investigate flight at not just supersonic speed, but at hypersonic speeds (above Mach 5), and one that would go to the limits of our atmosphere. NACA selected a team from North American Aviation led by Chief Project Engineer Charles Feltz to design the exotic plane, one that ultimately looked more like a spacecraft than an aircraft. And indeed, the X-15 was intended to fly in both regimes, using traditional flight control surfaces for flight in the atmosphere and reaction controls in the form of hydrogen peroxide thrust rockets for control in the thin air outside the atmosphere. Power for the X-15 came from a single liquid fuel Reaction Motors XLR99 rocket that produced over 70,000 pounds of thrust, though the early flights were carried out using two less powerful rocket motors.

The X-15 made its maiden flight on June 8, 1959 as part of a captive-carry mission with its Boeing NB-52A Stratofortress mother ship. For its first powered flight three months later, North American test pilot Scott Crossfield flew the X-15 to a rather pedestrian speed (for the X-15) of 2,242 mph, about Mach 3, at an altitude of around 16,000 feet. Other test flights went ever faster, eventually reaching a speed of 4,519 mph (7,273 kmh) on October 3, 1967, a record that still stands for a manned aircraft. But it wasn’t all about speed. The X-15 was also about altitude, and reaching the edge of space. In arcing flights that started in Utah, flew over Nevada, and ended at Edwards Air Force Base in California, 13 of the 199 test flights took their pilots to an altitude between 50-60 miles, the entry altitude to space set by the USAF. Flights 90 and 91, piloted by Joseph Walker, reached 66 and 67 miles. Pilots who made these flights were awarded their Astronaut wings (the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale Sporting Code sets the required altitude to be considered an astronaut as 100 km, about 62 miles).

The X-15 test program collected reams of data on hypersonic flight, as well as data that would be used for future aircraft and spacecraft design. A total of three X-15s were built during the program, and two survive. One is on display at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC, and the other resides at the National Museum of the United States Air Force in Dayton, Ohio.

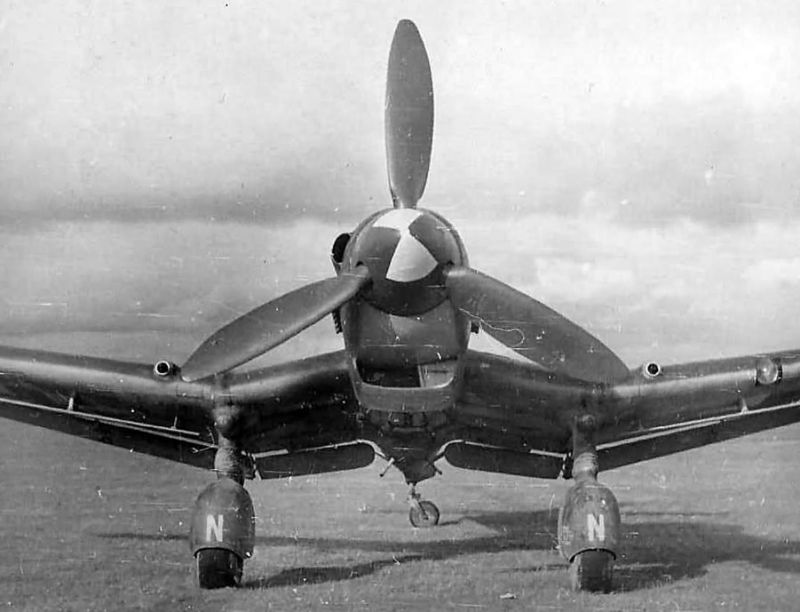

September 17, 1935 – The first flight of the Junkers Ju 87. In the early stages of WWII, the German Blitzkrieg (lightning warfare) was practically unstoppable as the German army stormed across Europe. Concentrations of armored or motorized infantry and tanks struck against Poland, France and the Low Countries hard and fast, but one of the main reasons for the success of the Blitzkrieg strategy was the use of combined arms tactics, with aircraft in close air support of the infantry. The plane that came to symbolize Blitzkrieg more than any other was the Junkers Ju 87 Stuka.

Development of a dedicated ground attack aircraft began as early as 1928. Once Adolf Hitler came to power in 1933, the project became one of great importance, and development was spearheaded by Ernst Udet, a WWI fighter ace and the eventual Director-General of Equipment for the Luftwaffe. Work on the Ju 87 began in 1933 as part of Germany’s Sturzbomber-Programm (the name Stuka is derived from Sturzkampfflugzeug, or diving warplane). With some irony, the aircraft was originally powered by a British Rolls-Royce Kestrel V-12 engine, and featured a twin tail to give the rear defensive gunner a clearer field of fire. But the weakly constructed tail broke apart during a test flight, killing the crew, and designers reverted to a more traditional single vertical stabilizer.

The Stuka’s distinctive inverted gull wings were adopted to provide clearance for the landing gear and to improve visibility for the pilot. Automatic pull-up dive brakes allowed the aircraft to recover from a diving attack even if the pilot lost consciousness from high G forces. Fixed, spatted landing gear, which hearkened back to an earlier era of aviation, added strength to the Stuka, and Jericho-Trompete wailing sirens were fitted to the struts as instruments of propaganda meant to strike fear into the Stuka’s targets. For the production aircraft, the original Rolls-Royce engine was swapped for one of German build, a Junkers Jumo 211 inverted V12, the same engine flown in the Junkers Ju 88 and Heinkel He 111.

Stukas first saw service in support of the General Francisco Franco’s Nationalists during the Spanish Civil War of 1936, and the dive bomber was instrumental in German victories in the first two years of WWII. Stuka’s worked closely with tanks and infantry to spearhead the invasion of Poland in September 1939, were instrumental in the conquering of northern continental Europe, and were also particularly effective against shipping. But in spite of its prowess as a dive bomber, the Stuka suffered from low speed and poor maneuverability, making it easy prey for faster, more agile Allied fighters. With a maximum speed of just about 240 mph, the Stuka was 100 mph slower than the Hawker Hurricane. As the war progressed, Stuka raids required fighter escort and, when Germany eventually lost air superiority over Europe, the Stuka was rendered much less effective. The bulk of the ground attack missions were taken over by attack variants of the Focke-Wulf Fw 190, but the Ju 87 soldiered on and served until the end of the war and was quickly retired. Of the more than 6,500 that were produced, only two remain. One is on display at the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago, and the other resides at the Royal Air Force Museum in London.

Short Takeoff

September 14, 2006 – The crash of USAF Thunderbird Number 6 during an air show at Mountain Home Air Force Base. Immediately after takeoff, Thunderbirds opposing solo pilot Captain Chris Stricklin attempted a Split S maneuver after incorrectly entering the mean-sea-level of the air base into his altimeter. Coming out of the maneuver too low, Stricklin ejected eight-tenths of a second before impact and suffered only minor injuries. His aircraft was destroyed. Following the crash investigation, procedures for the Split S were changed to add 1,000 ft more altitude before attempting the maneuver. Annotated video of the crash can be found here. Video with pilot radio can be found here.

September 14, 1963 – The first flight of the Mitsubishi MU-2, a twin-turborop utility aircraft for civil and military use and one of the most successful aircraft to be produced in postwar Japan. Following the flights of the prototypes, Mitsubishi partnered with Mooney Aircraft in the United States to assemble the aircraft in their San Angelo, Texas factory, with major components shipped from Japan. The Japanese Self-Defense Forces became the only military operator of the MU-2, though they are also flown under government contract by the US Air Force to provide students with battle management training. A total of 704 were produced from 1963-1986.

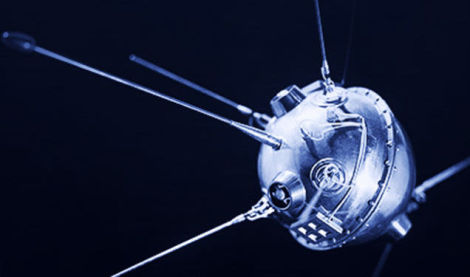

September 14, 1959 – The Soviet probe Luna 2 crashes onto the Moon. During the Space Race with the United States, the Soviet Union carried out the Luna program which attempted to send a series of 24 robotic spacecraft to the moon. Luna 1, launched in January 1959, missed the Moon, though it became the first spacecraft to orbit the Sun. Luna 2, launched on September 12, 1959, did make it to the Moon and became the first man-made object to reach the Moon and the first to land on another celestial body. Luna 2 carried instruments to measure the electron spectrum of the outer Van Allen Radiation Belt of the Earth and also searched for radiation belts around the Moon.

September 14, 1917 – The first flight of the Fairey III, a reconnaissance biplane built during WWI to meet a specification for a carrier-based seaplane. The Fairey III, also known as the F.128, was powered by a series of engines culminating in the Napier Lion 12-cylinder engine and had wings that could fold for carrier storage. Though it saw only limited service in WWI, development of the Fairey III continued between the wars and included a version with floats for operation from the surface of the water. Ultimately a very successful design, a total of 964 were built, and some were still in use in the early years of WWII.

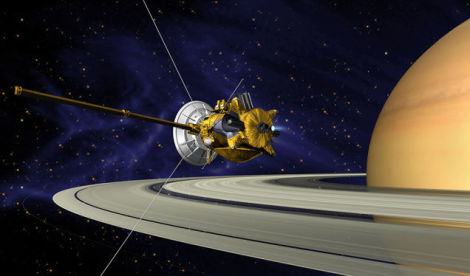

September 15, 2017 – The Cassini orbiter is intentionally crashed on Saturn. Launched on October 15, 1997 as a combined effort between NASA, the European Space Agency, and the Italian Space Agency, Cassini-Huygens was a two-part robotic spacecraft comprised of the Cassini orbiter and the Huygens lander. The paired spacecraft passed by Venus and Jupiter before beginning its orbit of Saturn on July 1, 2004, and the Huygens lander descended to the moon Titan on January 14, 2005. The landing was the first on a body in the outer Solar System and the first landing on a moon other than Earth’s moon. Huygens transmitted photos and other data via Cassini back to Earth, while Cassini continued to orbit Saturn. The so-called Grand Finale of the mission saw Cassini fly between the planet and its rings 25 times and return photographs of Saturn’s atmosphere. In order to avoid potential contamination of Saturn’s moons, which might have conditions suitable for life, Cassini was intentionally deorbited to the Saturn’s atmosphere to burn up the orbiter and destroy the spacecraft’s plutonium fuel.

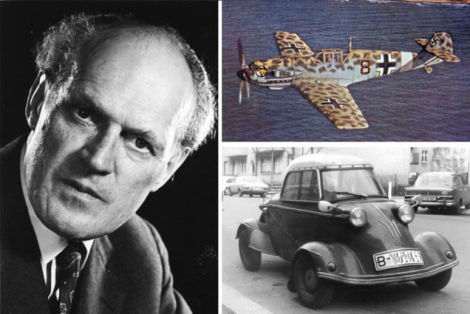

September 15, 1978 – The death of Willy Messerschmitt. Born in 1898, Messerschmitt began his design career building sail planes during WWI, then moved on to build small sport planes and small passenger planes. In 1936, he won the competition to provide the Luftwaffe with a new frontline fighter, the Bf 109, one of the war’s iconic fighters and an aircraft which was produced in greater numbers than any other aircraft in history. Faced with restrictions placed on the production of military equipment after the war, Messerschmitt turned to the manufacture of sewing machines, prefabricated buildings, and the Messerschmitt Kabinenroller automobile. He also exported his aircraft design talents to other countries, and designed the Hispano HA-200 jet trainer for Spain in 1952 before he was allowed to return to aircraft manufacturing, producing the Fiat G91 and the Lockheed F-104 Starfighter under license for the West German Luftwaffe. His final design was the Helwan HA-300, supersonic interceptor for the Egyptian air force.

September 15, 1969 – The first flight of the Cessna Citation I, a business jet developed by the Wichita-based Cessna Aircraft Company and the first in a line of business jets. Development began in 1968 when Cessna chose to market a smaller bizjet that would compete with current turboprop aircraft instead of the established bizjet market. Unlike the competing Learjet 25, which was powered by turbojets, the Citation I was powered by Pratt & Whitney Canada JT15D turbofans and, though it was slower, the addition of thrust reversers made it compatible with shorter airfields. The Citation I was produced from 1969-1985, and a total of 689 were built.

September 15, 1911 – The death of Édouard Nieuport, a French aviation pioneer and founder, along with his brother Charles, of the Société Anonyme Des Éstablissements Nieuport, better known simply as Nieuport. Édouard was known for his monoplane designs in an era when most manufacturers were producing biplanes, and he set speed records flying his own aircraft powered by engines of his own design. Édouard was killed in a flying accident in 1911, followed two years later by the death of his brother Charles, also in a flying accident. Despite the brothers’ deaths, their company went on to become one of the major manufacturers of fighter aircraft in WWI.

September 16, 2013 – The first flight of the Bombardier CSeries (CS100), a narrow-body twin-engine medium-range regional airliner manufactured by Bombardier Aerospace of Canada. Following their unsuccessful takeover of Fokker in 1996, Bombardier considered a new regional jet, but instead chose to enlarge their existing successful line of CRJ regional jets. With the launch of the Embraer E-Jet line in 2002, Bombardier revisited their original idea and developed their first regional jet with 5-across seating and engines in pods under the wing rather than at the rear of the aircraft. After a lengthy test program, the first CS100 was delivered to Swiss Global Air Lines in June 2016, with Bombardier having firm orders for 123 more CS100 airliners along with 235 of the larger CS300. In 2017, Bombardier formed a partnership with Airbus which saw the European manufacturer take a 50.01% share of the company, and the CS100 was then rebranded as the Airbus A220.

September 16, 2011– A modified North American P-51D Mustang crashes into the grandstands at the Reno Air Races. Seventy-four-year-old Jimmy Leeward was piloting his highly modified North American P-51D Mustang (NX79111) around pylon number 8 at the Reno Air Races in Nevada when the aircraft suddenly pitched up violently and plunged into the grandstands, killing Leeward along with 10 spectators. During the race, Leeward reached a top speed of 530 mph, and investigators later determined that the trim tab on the left elevator began to flutter before breaking off and causing a loss of control. The sudden departure from controlled flight exerted 17Gs on the Leeward, which would have rendered him unable to move and likely caused him to lose consciousness. The breakage was traced to the reuse of locknuts that were only designed to be used once. The crash was the fourth-deadliest accident in US air show history.

September 16, 1959 – The first flight of the North American Sabreliner, a mid-sized business jet designed by North American Aviation for both the military and civilian markets. Development began as part of the US Air Force’s Utility Trainer Experimental (UTX) program to find an aircraft that could function both as a utility transport and a combat readiness trainer, and the name Sabreliner was chosen due to the resemblance of the tail and wings to the North American F-86 Sabre fighter. The US military adopted the Sabreliner as the T-39, while the civilian version was originally marketed as the Series 40, though subsequent variants saw the 60, 70, 75 and 80. The Navy also adopted the T-39 for radar operator training. More than 800 Sabreliners were produced from 1959-1982.

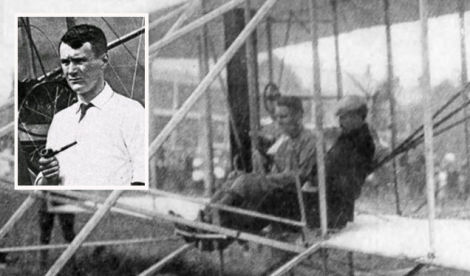

September 17, 1908 – Thomas Selfridge is the first person in history to die in an airplane crash. Selfridge was born on February 8, 1882 and served in the Aeronautical Division of the US Army Signal Corps after his graduation from the United States Military Academy in 1903. As part of an effort to build interest from the US Army in airplanes, Orville Wright traveled to Fort Myer near Washington, DC to demonstrate the Wright Flyer to Army officials. On the fateful flight, Orville piloted the Flyer around the base and Selfridge rode as a passenger while the plane reached an altitude of 150 feet. On the fifth circuit, the right propeller broke, and pieces of the prop damaged the struts and wiring of the Flyer. The aircraft plunged straight down from an altitude of approximately 125 feet. Orville was severely injured, but Selfridge died later that day from a fracture to the base of his skull, making him the first person in history to die in a plane crash.

Connecting Flights

If you enjoy these Aviation History posts, please let me know in the comments. And if you missed any of the past articles, you can find them all at Planelopnik History. You can also find more stories about aviation, aviators and airplane oddities at Wingspan.