Welcome to This Date in Aviation History, getting of you caught up on milestones, important historical events and people in aviation from September 21 through September 24.

September 21, 1964 – The first flight of the North American XB-70 Valkyrie. During the Second World War, strategic bombing evolved into an extremely destructive endeavor, and rose to an earth-shattering crescendo with the nuclear attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki that finally brought an end to the most destructive war in human history. The Nuclear Age had dawned, but the intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBM) that we know and fear today were yet to be developed. Attacking an enemy with nuclear weapons was still a mission for long-range bombers and, like their predecessors, early postwar bombers remained susceptible to fighters and interceptors. But with the arrival of supersonic bombers, it was hoped that these planes could fly at altitudes and speeds beyond the reach of contemporary interceptors, and such was the genesis of the radical North American XB-70 Valkyrie. However, by the time the Valkyrie finally took to the air, the ICBM had taken over the role of nuclear attack, and the Valkyrie became an anachronism, a bomber for an earlier age.

In 1955, the US Air Force issued a requirement for a new strategic bomber that would have the payload capacity of the Boeing B-52 Stratofortress but the supersonic speed of the Convair B-58 Hustler. Various radical designs were considered, but the rapid development of supersonic science indicated that a large delta wing, with forward canards for added stability and control, would be the most efficient shape for such a bomber. Initially, the Air Force planned for a bomber that would fly to the target, drop the bomb from lower altitude, and then “scoot” away from the blast at supersonic speed. But engineers discovered that, from the standpoint of fuel use versus miles traveled, it was actually more efficient for the bomber to spend its entire mission at top speed.

In the case of the XB-70, that top speed would be Mach 3 at 70,000 feet, propelled by six General Electric YJ93 afterburning turbojets, all mounted side by side in what came to be known as the “six pack.” That sort of performance generated a lot of heat, so fuel was pumped through heat exchangers before flowing to the engines in order to keep the aircraft cool. North American engineers also discovered a way to make use of a phenomenon known as compression lift, where the shock wave made by the plane helped create lift. Drooping wingtips allowed the Valkyrie to take full advantage of this effect, with the added benefit of decreasing drag.

Though the XB-70 would be unreachable by any contemporary fighters, advances in air-to-air missiles suddenly put the whole project in doubt, causing the Air Force to switch its doctrine from high altitude supersonic bombing to low altitude penetration. Thus, the Valkyrie would have to be flown at low levels, where it was barely faster than the B-52, while carrying a smaller payload. Ultimately, the XB-70 became a Cold War Era political football, the stuff of campaign promises and political bargaining, and the project was canceled in 1961. With no real bombing mission for the plane to perform, the two XB-70s that were completed became testbeds for supersonic research. On June 8, 1966, Valkyrie No. 2 was lost in a mid-air collision during a formation flight photo shoot for engine manufacturer GE that caused the death of two pilots and the serious injury of a third. Aircraft No. 1 continued to serve in its research role, and made its final supersonic flight in February 1969 when it was flown to the National Museum of the United States Air Force in Dayton, Ohio.

September 21, 1961 – The first flight of the Boeing CH-47 Chinook. When the US Army placed an order for the Sikorsky R-4 in 1943, it marked the beginning of a relationship with rotor wing aircraft that would eventually give rise to the practice of vertical envelopment that became the primary means of attack during the Vietnam War. But the Army soon realized that, while smaller helicopters were good at moving soldiers, they needed something bigger to lift artillery, heavy equipment, and even greater numbers of soldiers. For a time, that role was filled by the Sikorsky CH-37 Mojave, but work began in 1957 to procure a modern, turbine-powered helicopter as a replacement for the Mojave that could provide more lifting power and higher speeds than the CH-37's pair of radial engines could provide.

Opinion in the Army was split over just what sort of helicopter this would be. One group imagined it as a helicopter capable of carrying a full squad of 15 soldiers, while the other group wanted a much larger helicopter that could transport artillery pieces and other battlefield supplies. Ultimately, the second group carried the day, and Vertol began working on a tandem helicopter, with two rotors providing extra lift for heavy loads. (Before being acquired by Boeing in 1960, Vertol was originally Piasecki Helicopter, whose founder Frank Piasecki was an early advocate of tandem helicopter design.) The first helicopter to come out of the Army requirement was the YHC-1A, but the Army deemed that it was too small, though it was eventually adopted by the US Marine Corps as the Boeing Vertol CH-46 Sea Knight in 1962, where its smaller size would be an advantage for the carrier-based Marines. So Boeing Vertol enlarged the YCH-1A into the YCH-1B, which finally became the CH-47 Chinook following the Army tradition of naming helicopters after Native American tribes. The larger helicopter was powered by a pair of Lycoming T55 turboshaft engines each producing 4,733 hp and turning counter-rotating propellers. The two engines gave the Chinook a top speed of 170 knots, faster than the utility and attack helicopters of its day. They also supplied enough power to carry up to 55 troops or 28,000 pounds of cargo.

The Chinook entered service with the Army in Vietnam in 1965, where its size quickly became invaluable in the supply of forward bases. Its lifting power also made it possible to haul artillery pieces to remote mountaintop fire bases that were unreachable by roads. Not only was the Chinook popular with the US Army, but it was exported to 23 nations and remains in production, with over 1,200 aircraft built, making it the most-produced tandem helicopter in history. Continuously upgraded since its introduction, the Chinook now has newer, more powerful Lycoming engines (now produced by Honeywell), composite rotor blades, redundant electrical systems and advanced avionics. Along with its fixed-wing heavy lifting counterpart, the Lockheed C-130 Hercules, the CH-47 is one of the few aircraft that has seen a production and service life of over 50 years.

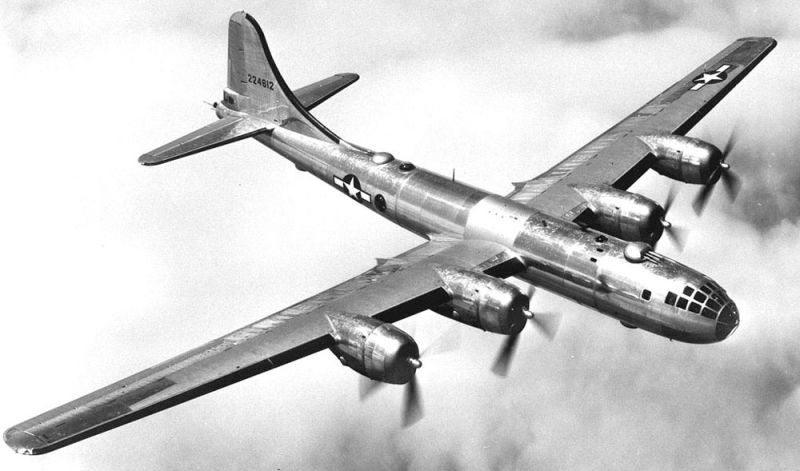

September 21, 1942 – The first flight of the Boeing B-29 Superfortress. In the years leading up to WWII, there were two main schools of thought about how best to use bombers. One was strategic bombing, which sought to defeat the enemy by destroying their means of production of war materiel while also destroying the morale of the civilian population. The other was tactical bombing, in which bombers worked more closely with ground troops to carry out specific battlefield operations and destroy targets of immediate military value. While Germany, with their Blitzkrieg warfare, became almost wholly invested in the theories of tactical bombing, America and her allies followed the doctrines of strategic bombing, particularly the theories espoused by Italian general Giulio Douhet and American general Billy Mitchell. To that end, the Americans produced ever larger bombers, capable of carrying heavy loads of bombs at great distances. When the Superfortress entered service in 1944, it was the most technologically advanced bomber of its era. And even though it arrived late in the war, it had a profound effect on the later stages of the Pacific campaign.

Boeing’s work on a pressurized bomber began all the way back in 1938 as an independent project. Then, in 1939, at the urging of Charles Lindbergh, the Army began to pursue a so-called “superbomber,” one that would be capable of carrying 20,000 lbs of bombs over 2,600 miles at a speed of 400 mph. Boeing’s previous work formed the basis for their entry into a competition between Boeing, Consolidated, Lockheed and Douglas to produce the new bomber, and Boeing received an order for two prototypes in August 1940. By May of 1941, the order was increased to 250 production bombers, and then to 500 in January 1942. The Consolidated B-32 Dominator, a more traditional design that was not selected in the initial competition, was ordered into production in smaller numbers should the production of the B-29 run into difficulties.

At the time the B-29 was being developed, the piston-powered aircraft was reaching the zenith of technological advancement, and the Superfortress was at the forefront. In addition to its streamlined shape and the adoption of pressurization, the B-29 was armed with up to ten Browning M2 .50 caliber machine guns in remotely operated, motorized turrets. With onboard targeting computers and a system that could link the guns together, one gunner could control two or more sets of guns to focus the greatest amount of firepower against enemy fighters. And that was only if the fighters could reach the high-flying bomber. Operating at nearly 32,000 feet and at speeds of up to 350 mph, the B-29 was almost unreachable by most Japanese fighters. But as good as design of the B-29 was, serious problems with the complex Wright R-3350 Duplex-Cyclone radial engines plagued the early development of the new bomber. Those problems were eventually ironed out, but it wasn’t until the introduction of Pratt & Whitney R-4360 Wasp Major engine after the war that the problems were mostly solved.

The Army Air Forces originally intended the B-29 to be used against Germany, but delays in production meant that it was flown exclusively against Japan in the Pacific Theater. The B-29's extreme range proved a vital asset as it attacked far-flung Japanese targets and later the island of Japan itself from bases in China. Later, the bombers relocated to bases built on Pacific islands captured captured during the Allies’ island hopping campaign, eliminating the need to fly over the Himalayas. When conventional bombs proved less effective against the scattered Japanese military infrastructure, B-29s were flown in devastating firebombing raids against Japanese cities. By the summer of 1945, specially modified Silverplate B-29s were used in the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki that hastened the end of the war.

While most WWII-era bombers were retired in 1945 with the end of the war, the Superfortress continued its career and flew bombing missions early in the Korean War, and its advanced design allowed it to be transformed into a number of variants that flew into the jet age. As the KB-29, it served as the basis for one of the first aerial refueling tankers, and the upgraded B-50 flew until 1965, primarily in the reconnaissance role. The Superfortress also formed the basis for the Boeing C-97 Stratofreighter, the Boeing 377 Stratocruiser passenger airliner and the Pregnant/Super Guppy series of large cargo aircraft. Though nearly 4,000 Surperfortresses were produced, only two remain flying today.

September 24, 1949 – The first flight of the North American T-28 Trojan. The career of any military pilot begins with primary flight training carried out in a two-seat trainer, with one seat for the student and one for the instructor. Since before WWII, most American pilots flew the North American T-6 Texan, one of aviation history’s truly great airplanes which became the primary trainer for no less than 61 nations and ultimately served for 60 years. But even a great plane like the Texan would need to be replaced one day. When that time came, though, the US military didn’t look for just a trainer. They hoped to adopt an aircraft that would also work well in the close air support (CAS) and ground attack roles.

Based on the success of the T-6, the US Navy and Air Force once again turned to North American Aviation, and the aircraft that the storied company came up with proved to be every bit as effective as the one it was meant to replace. Like the Texan, the Trojan was a simple, rugged, straight-wing aircraft. It was powered by a Wright R-1820 Cyclone nine-cylinder supercharged radial engine, the same one that powered many of the great warplanes of WWII such as the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress, the Curtiss SB2C Helldiver, and a host of other military aircraft and helicopters. The Cyclone provided a top speed of 343 mph with a climb rate of 4,000 feet per minute, and the two pilots were housed under a frameless canopy that afforded excellent visibility for both instructor and student.

The T-28A first entered service with the US Air Force, and was quickly adopted by the US Navy and US Marine Corps in two variants: the T-28B, which was similar to the Air Force version but with a more powerful engine, and the T-28C, which was designed for carrier operations with a smaller propeller and added arrester hook. In the ground attack role, units of the South Vietnamese Air Force flew an armed variant of the Trojan known as the T-28D Nomad in the counterinsurgency (COIN) role, as well as reconnaissance, search and rescue, and forward air control. For dedicated ground attack missions, the AT-28D provided a sturdy, flexible platform with six underwing hardpoints that could carry bombs, rockets, or napalm for ground attack missions, and was also fitted with an ejection seat. Trojans also served as an armed escort for attacks by Douglas A-26 Invaders or attack helicopters.

While the Air Force phased the Trojan out of service by the 1960s, it continued to serve the Navy and Marines well into the 1980s before being replaced by the turboprop-powered Beechcraft T-34 Mentor. And, like its predecessor, the Trojan was widely exported, serving a total of twenty-eight international customers, with nearly 2,000 produced from 1950-1957. The last T-28 was retired by the US Navy in 1984, but the aircraft served for another ten years with the Philippine Air Force, and privately-owned Trojans remain popular performers on the air show circuit.

Short Takeoff

September 21, 2012 – The Space Shuttle flies atop the Shuttle Carrier Aircraft (SCA) for the last time. With the end of the Space Shuttle program in 2011, the retired Shuttles were distributed to various museums and sites around the country. Endeavour was the last to be delivered and, during its ferry flight, the SCA made low passes over Florida’s Space Coast and NASA centers in Mississippi and Louisiana before landing in Houston to refuel. Next, it flew over the White Sands Test Facility in New Mexico, over Tucson, Arizona as a tribute to Congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords, then on to Edwards Air Force Base in California where many Shuttle landings took place. On the final leg of the flight, the SCA and Endeavour made low level passes over Sacramento, San Francisco, Silicon Valley, and Los Angeles, before landing at Los Angeles International Airport. Endeavour is now on display at the California Science Center in Los Angeles.

September 21, 1984 – The first flight of the Dassault Falcon 900, a business jet produced by Dassault Aviation of France and, with its sister ship the Falcon 7X, the only trijets currently in production. The Falcon 900 is the continuation of the line of Falcon jets that began with the Falcon 20 and continued with the Falcon 50. With a crew of two, the Falcon 900 can accommodate up to 19 passengers, and its three Honeywell TFE731 turbofans provide a top speed of Mach 0.87 and an intercontinental range of over 4,000 miles. More than 500 have been built since production began in 1984, and the 900 remains in production today.

September 21, 1945 – The first flight of the Hawker Sea Fury, the last piston-powered fighter developed by England during WWII. When the RAF canceled their order at the end of the war, Hawker developed a carrier-based version for the Royal Navy. Powered by a Bristol Centaurus 18-cylinder radial engine, the Sea Fury was the last propeller-driven fighter to enter service with the Royal Navy and, with a top speed of 460 mph, one of the fastest single piston-engined aircraft ever built. Introduced in 1947 and sold to nine export countries, the Sea Fury saw action during the Korean War, and was flown by the Cuban Fuerza Aérea Revolucionaria (Revolutionary Air Force) during the 1961 Bay of Pigs Invasion. A total of 864 were produced, and the last Sea Furys were retired by the Burmese Air Force in 1968.

September 22, 2006 – The Grumman F-14 Tomcat is retired by the US Navy. Developed after the the US Navy’s rejection of the General Dynamics F-111B carrier-based interceptor, the F-14 became the Navy’s primary fighter, though it retained the engines, weapons system and variable geometry wing of its unsuccessful predecessor. The Tomcat entered service with the US Navy in 1974, replacing the McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom II, and served as the Navy’s principal air superiority fighter while also performing fleet defense and reconnaissance missions. With the arrival of the Boeing F/A-18E/F Super Hornet in 1999, the Tomcat was phased out, with its official retirement taking place in 2006 after 32 years of service. Many Tomcats reside in museums, but retired operational F-14s were scrapped by the US government to prevent their parts being obtained by Iran, the sole export customer for the Tomcat before the Iranian Revolution toppled the Shah of Iran.

September 23, 1938 – The first flight of the Supermarine Sea Otter, an amphibian aircraft developed for the Royal Navy and Royal Air Force before WWII and the last biplane to be flown by either service. The Sea Otter was a development of the earlier Supermarine Walrus, with the principal difference being the placement of a single Bristol Mercury radial engine in the center of the upper wing in a puller configuration rather than between the wings as a pusher. The Sea Otter entered service in 1942 and carried out air-sea rescue missions and maritime reconnaissance, while postwar aircraft flew small numbers of passengers and cargo. Just under 300 were built before the end of the war halted production.

September 24, 1930 – The birth of John Young, an American aeronautical engineer, US Naval Aviator, test pilot, and astronaut. Young began flying with the US Navy as a helicopter pilot in 1954 before transferring to jets, and joined NASA in 1962 as a member of Astronaut Group 2. During his time with the space agency, Young made six space flights, including the first manned Project Gemini mission. In 1969 he became the first man to orbit the Moon alone during Apollo 10, drove the Lunar Roving Vehicle on the Moon during Apollo 16 in 1972, and is one of only three people who have flown to the Moon twice. Young is also the only person to have piloted four different classes of spacecraft, including the first launch of the Space Shuttle program in 1981. Young’s retirement from NASA in 2004 marked the end of the longest career of any NASA astronaut.

September 24, 1929 – Lieutenant James H. “Jimmy” Doolittle makes the first blind flight using only instruments. Flying a Consolidated NY-2 Husky with instruments that included a sensitive altimeter, a directional gyro developed by the Sperry company, and a radio range finder, Doolittle, along with safety officer Lt. Benjamin Kelsey in the front cockpit, took off from Mitchel Field in New York and flew a prescribed course which covered 20 miles and lasted 15 minutes. From takeoff to landing, Doolittle was underneath a hood in the rear cockpit and was flying completely blind. The flight proved the capabilities of the new instruments, and opened a new era of flight safety where pilots could rely on instruments rather than instinctive “seat of the pants” flying.

September 24, 1918 – US Navy Lt. David Ingalls becomes the first US Navy fighter ace. Ingalls enlisted in March 1917 as Naval Aviator No. 85 and was sent to Europe six months later attached to RAF No. 213 Squadron, where he flew a Sopwith Camel from a base in Dunkirk in northern France. With six credited victories by the end of the war, Ingalls was the first fighter ace in US Navy history and the Navy’s only ace of WWI. For his service, Ingalls received the US Navy Distinguished Service Medal, the British Distinguished Flying Cross and the French Legion of Honour. Following the war, Ingalls became a director of Pan Am World Airways and assisted Charles Lindbergh with charting eastern air routes for Pan Am.

Connecting Flights

If you enjoy these Aviation History posts, please let me know in the comments. And if you missed any of the past articles, you can find them all at Planelopnik History. You can also find more stories about aviation, aviators and airplane oddities at Wingspan.