Welcome to This Date in Aviation History, getting of you caught up on milestones, important historical events and people in aviation from September 25 through September 27.

September 26, 1965 – The first flight of the LTV A-7 Corsair II. Throughout the history of military aviation, there have been a handful of aircraft that were named after successful predecessors, such as the Fairchild Republic A-10 Thunderbolt II, which took its name from the potent P-47 Thunderbolt fighter and ground attack aircraft of WWII, and the McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom II, which continued the use of ghostly aircraft nicknames that started with the FH Phantom in 1945. So, when Ling-Temco-Vought (LTV) needed a nickname for their new hard-hitting ground attack aircraft, they found inspiration in the rugged and deadly Vought F4U Corsair of WWII and Korea, one of the preeminent fighters of the piston era.

In 1962, the US Navy began a search for a new attack aircraft to replace the Douglas A-4 Skyhawk, hoping to improve both the range and payload provided by the diminutive A-4. The Navy also required that the new attack aircraft show improvements in target accuracy in order to reduce the costs associated with bombs that missed their mark. By 1963, the Navy finalized their requirements and announced the VAL (heavier-than-air, attack, light) competition and, to save money, they stipulated that the aircraft be based on an existing design. Vought turned to their F-8 Crusader, a supersonic air superiority fighter that entered service with the Navy in 1957. But the Crusader was built for speed, with a long narrow fuselage and afterburning turbojet engine, and ground attack missions call for subsonic speeds closer to the ground. So Vought shortened and broadened the fuselage and removed the variable incidence wing that helped lower the Crusader’s landing speeds. They also increased the wingspan and replaced the Crusader’s afterburning turbojet with an Allison TF41 turbofan that had no afterburner, since there would be no need for the A-7 to fly at supersonic speeds. Vought gave the A-7 an AN/APQ-116 radar that offered better targeting than the McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom II, and also installed a head-up display (HUD), the first for a US fighter. The Navy selected the A-7 as the winner of the VAL competition in 1964, and it received the nickname Corsair II a year later.

By 1967, Navy A-7s were in action over Vietnam, flying from the aircraft carrier USS Ranger (CVA-61). However, the hot humid conditions of Southeast Asia limited the amount of power available to Navy pilots, and they could not carry a full load of weapons and fuel. The lack of power led pilots to nickname the Corsair II “SLUF,” which stood for Short Little Ugly Fucker. The Corsair II was also pressed into service with the US Air Force when they identified the need for a robust subsonic ground attack aircraft to support US Army troops. Reluctant at first to take the Navy airplane, the Air Force relented under pressure from Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, with the stipulation that their version would have a still more powerful engine and an M61A1 rotary cannon rather than the two single-barreled 20mm cannons on the Navy version. This aircraft was designated the A-7D, and was later adopted by the Navy as the A-7E. All told, the Navy and Air Force flew more than 100,000 A-7 sorties during the war.

By the end of the Vietnam War, the Air Force began passing the Corsair II over to the Air National Guard (ANG) in favor of the F-4 Phantom II, but the Navy continued flying A-7s, and they saw action over Grenada and Libya, and limited use in the First Gulf War. The Air Force and Navy retired their A-7s in 1991, while the ANG finally retired their Corsair IIs in 1993. The Greek Hellenic Air Force flew the A-7 until 2014, 47 years after the type’s maiden flight.

September 27, 1964 – The first flight of the BAC TSR-2. By the 1950s, the general doctrine of aerial bombardment, either nuclear or conventional, was to penetrate enemy territory by flying as high and fast as possible, beyond the reach of enemy fighters and interceptors. In England, the English Electric Canberra, which first flew in May 1949, had a service ceiling of 48,000 feet, and could fly over enemy territory with relative impunity. But the arrival of the surface-to-air missile (SAM) changed the conventional bombing doctrine practically overnight, and a new breed of attack aircraft came to the fore, known as interdictors. Since radar-guided SAMS of the era worked on line of sight to track incoming targets, the new bombing method was to fly as low as possible, under the radar, and use terrain features to further mask the attacking aircraft. These high speed, ground-hugging aircraft could carry either conventional or nuclear weapons, and their interdictor role called for them to fly deep behind enemy lines and destroy logistics targets such as airfields and railroad hubs, thus preventing the enemy from bringing troops and supplies to the front lines.

To that end, the British government issued Operational Requirement 399 (GOR.399) in 1956, an extraordinarily ambitious list of requirements for a new light bomber that would fly at supersonic speeds in all weather conditions, be capable of carrying both tactical nuclear weapons and conventional weapons, have either short takeoff and landing (STOL) or vertical takeoff and landing (VTOL) capabilities, and be able to perform both bombing and reconnaissance missions. In January 1959, the Ministry of Supply selected a consortium of Vickers-Armstrongs and English Electric (which, along with the Bristol Aeroplane Company and Hunting Aircraft were forced into a merger in 1960 to form the British Aircraft Corporation, or BAC) to produce what would be called the TRS-2 (Tactical Strike Reconnaissance, Mach 2). The new aircraft was designed around the strengths of each company, with Vickers-Armstrongs building the front half of the aircraft and wings, while English Electric built the rear.

The TSR-2 was powered by two Bristol-Siddeley Olympus afterburning turbojets developed from those used on the Avro Vulcan, engines which would later power the Concorde. It was capable of a sustained cruise of Mach 2.05, with a dash speed of Mach 2.35, and a theoretical top speed of Mach 3. In an effort to save money, no prototypes were built. The first tranche of aircraft were supposed to be finished production aircraft, and testing commenced with the first two completed airframes. Despite some early mechanical difficulties, test pilots reported that the TSR-2 flew well. Still, the initial requirements had to be reworked to reflect the realities of the TSR-2's performance. Though the first aircraft was supposed to be a finished production airframe, the sophisticated radars and other electronics had yet to be installed, and the costs of the aircraft continued to climb.

Some in the British government believed that the TSR was made obsolete by the ICBM, and when combined with cost and complexity of the aircraft, as well as delays in development, the decision was made to cancel the program on April 6, 1965, the day scheduled for the maiden flight of the second aircraft. Following contentious debate, the British government announced that it would instead procure the General Dynamics F-111 rather than develop their own interdictor, even though considerable money and effort had already been put into the TSR-2. And, to add insult to injury, the British government later rescinded their order of F-111s when that program ran into it own costly delays. Within six months of cancellation, all uncompleted aircraft, plus all tooling, were scrapped. Only two aircraft survived, neither of which is complete. The two finished aircraft, including the one that took part in testing, were destroyed to test for weaknesses in the airframe to gunfire and shrapnel. Only one completed aircraft survived, and is housed at the RAF Museum, Cosford. A second airframe, much less complete, resides at the Imperial War Museum Duxford.

Short Takeoff

September 25, 2015 – The first flight of the Boeing KC-46 Pegasus, the newest aerial refueling and strategic airlifter slated to enter service with the US Air Force in late 2019 or early 2020. In 2011, the Pegasus was announced as the winner of the Air Force KC-X competion over a Northrop Grumman/Airbus offering in a protracted and often acrimonious debate over which aircraft would replace 100 older Boeing KC-135 Stratotankers. The Pegasus is based on the Boeing 767 widebody airliner and will have seating for up to 114 people or 65,000 pounds of cargo and will be capable of transferring over 207,000 pounds of fuel. The Air Force has placed an order for a total of 36 aircraft, and the tankers will be based at McConnell Air Force Base in Kansas. The first was delivered to the Air Force in January 2019, but problems with systems such as the remote controlled refueling boom, cargo tie downs, and FOD inside the aircraft have seriously delayed the operational capability of those aircraft delivered so far.

September 25, 1978 – A Pacific Southwest Airlines Boeing 727 and a private plane collide in midair over San Diego. PSA Fight 182, a Boeing 727 (N533PS), was approaching San Diego’s Lindbergh Field (now San Diego International Airport) when it collided with a Cessna 172 Skyhawk. The crew of the 727 had been alerted to the presence of the Cessna, but had lost sight of it and failed to notice when it made an unauthorized change of course. The pilot of the Cessna was under a hood practicing instrument landing system (ILS) approaches, but his instructor had no limitations on his vision and failed to see the 727. Air traffic control detected a conflict alert but did not warn the aircraft since they believed that they could see each other. The two aircraft came down in a residential area, killing 142 passengers and nine people on the ground. Following a similar mid-air collision in 1982, the FAA mandated that Traffic Collision Avoidance Systems (TCAS) be installed in all commercial airliners flying in US airspace.

September 25, 1945 – The first flight of the de Havilland Dove, a short-haul passenger plane that was designed as a feeder to larger airports and one of the most successful designs to come out of the Brabazon Committee in their search for a domestically produced British airliner following WWII. The Dove was a monoplane successor to the pre-WWII de Havilland Dragon Rapide biplane and had accommodations for eight passengers. De Havilland produced 542 Doves from 1946 to 1967, and it entered service in 1946, with the first aircraft purchased by Argentina. The Dove was widely exported, serving airlines around the world, and remains in limited service today.

September 26, 1951 – The first flight of the de Havilland Sea Vixen, a twin boom, twin-engine, all-weather, carrier-based fighter developed for the British Royal Navy Fleet Air Arm. Development of the Sea Vixen began in 1946 as the DH.110, and its twin boom design was borrowed from the de Havilland Venom. Where the earlier Venom had been constructed of a composite of wood and metal, the Sea Vixen was of all-metal construction. The Sea Vixen was powered by two Rolls-Royce Avon axial flow turbojets and was the first British fighter capable of supersonic speeds. It could be armed with a mixture of missiles, bombs, or rockets, but carried no internal gun. The Sea Vixen entered service in 1959 and, while it never saw combat, it was dispatched to flashpoints around the world throughout the 1960s wherever a show of military power was required.

September 26, 1912 – The death of Charles Voisin. Born on July 12, 1882, Charles Voisin was an early French pioneer of aviation who founded an aircraft manufacturing company with his brother Gabriel named Appareils d’Aviation Les Frères Voisin in 1906. The Voisins built airplanes to order for wealthy customers and used these aircraft to further their understanding of controlled flight. Their 1907 biplane, flown by Henri Farman, made the first heavier-than-air flight in Europe of more than one minute, and that aircraft, the Voisin-Farman 1, formed the basis of their fledgling company. Voisin died from injuries sustained in an automobile accident on September 25, 1912, but the company continued under his brother’s leadership, and produced aircraft for the French during WWI.

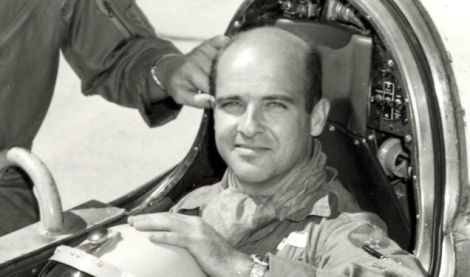

September 27, 1956 – Test pilot Milburn G. “Mel” Apt becomes the first to fly at Mach 3, but is killed when his aircraft crashes. Apt was born on April 9, 1924 in Buffalo, Kansas and joined the US Army Air Forces in 1944. Following his military service, Apt received a degree in aeronautical engineering and graduated from the Experimental Flight Test School in 1954. As a test pilot, Apt flew the Bell X-2 rocket plane and became the first person to exceed Mach 3, though the record-breaking flight ended in tragedy. After the rocket motor burned out, Apt attempted a turn back to base, still flying at Mach 3, and lost control of the X-2. As the aircraft tumbled through the sky, Apt initiated the separation of the escape capsule. The capsule’s drogue chute opened, but the main chute did not, and Apt was killed when the capsule struck the ground.

September 27, 1946 – The death of Geoffrey de Havilland, Jr, OBE. The son of famed aircraft designer Geoffrey de Havilland, Geoffrey de Havilland, Jr. was born on February 18, 1910 at Crux Easton, Hampshire. He served as the chief test pilot for the de Havilland Aircraft Company, piloted the maiden flights of the de Havilland Mosquito and the jet-powered de Havilland Vampire, and was awarded the Order of the British Empire in 1945. During a test flight of the de Havilland DH 108 Swallow, a radical tailless aircraft based on the Messerschmitt Me 163 Komet, de Havilland lost control of the aircraft before it broke up and crashed. Investigators determined that de Havilland had died when his head struck the canopy during the violent oscillations, breaking his neck.

Connecting Flights

If you enjoy these Aviation History posts, please let me know in the comments. And if you missed any of the past articles, you can find them all at Planelopnik History. You can also find more stories about aviation, aviators and airplane oddities at Wingspan.