The Wright Brothers changed the world with their First Flight in 1903, but in the years following the Wright’s success at Kitty Hawk the brothers spent more time securing and protecting their patents than they spent flying. Working largely in secret, they had improved their original design and were making longer and longer flights over Huffman Prairie in Ohio, but then parked their aircraft and didn’t fly again for three years. By 1912, Wilbur was dead from typhus, and Orville was left on his own. Though the pair had founded Wright Aeronautical in 1909 and sold the US military it first airplane, thereby creating military aviation in the US, the Wright Flyer never really changed much from its early form. Without his brother’s business acumen, Orville sold the company in 1915, and flew as a pilot for the last time in 1918, though he led a life dedicated to aviation until his death in 1948. It was their contemporary, Glenn Curtiss (who also began his career as a bicycle builder), that would arguably become the larger figure, even though today his name is not nearly as well known Orville and Wilbur.

Once he got started, Curtiss never stopped designing and refining airplanes, and pushed the science and art of aeronautics far beyond what the Wrights had begun. With the founding of the Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company in 1916, Glenn Curtiss essentially created the American aircraft manufacturing industry. He supplied aircraft to the US Army during WWI, and built more than 6,800 copies of the remarkable Curtiss Jenny, the ubiquitous biplane that came to symbolize the barnstorming era after the war. By this time, Wright had merged with another Glenn, Glenn Martin, and the Wright-Martin company made great strides in engine design. But Curtiss took control of that company in 1929, and the Wright name became subsidiary to their greatest competitor with the founding of Curtiss-Wright. Though Glenn Curtiss died at just age 52, his company lived on.

Under the Curtiss name, the company built some of the iconic aircraft of WWII, including the C-46 Commando cargo plane and the P-40 Warhawk fighter. But as the war progressed, the Curtiss company didn’t necessarily run out of ideas, it just ran out of successful ideas, and a string of prototype fighters, seaplanes, and cargo planes were either rejected by the US military or suffered problematic careers. The end of the war brought about huge cuts in defense spending, and all but one of Curtiss’ production facilities were shuttered. At the dawn of the jet era, Curtiss had just two cards left to play: the XF15C, a hybrid jet/piston-powered fighter for the US Navy, and a large all-weather interceptor for the US Air Force.

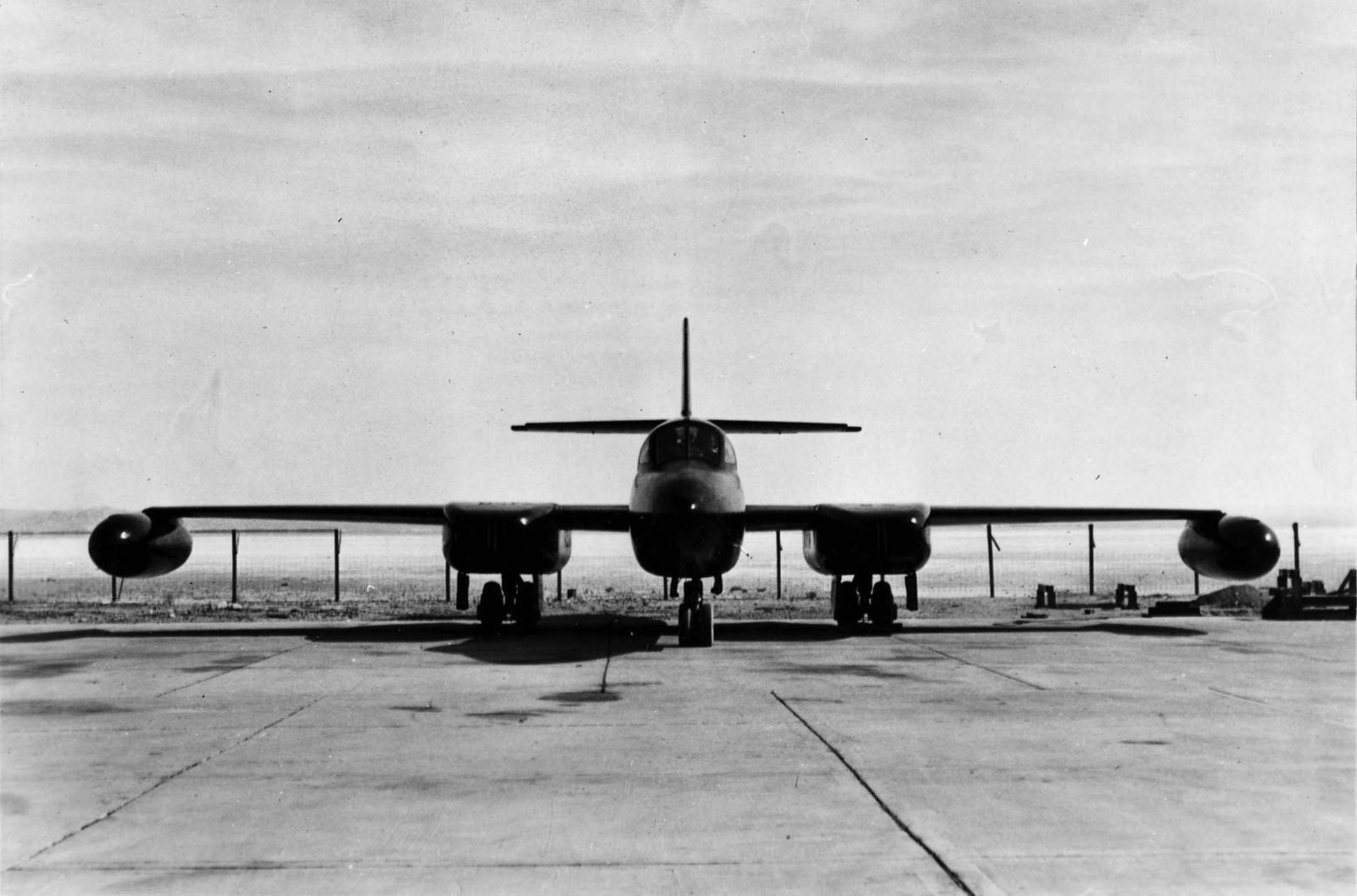

The XF-87 Blackhawk, in keeping with Curtiss’ tradition of using the Hawk name in some form, was a four-engine, two-seat, all-weather jet fighter that began its life as a piston-powered replacement for the Northrop P-61 Black Widow. But when the USAAF dictated a switch to jet engines, Curtiss missed the opportunity to modernize their design, and instead stuck with squared lines and straight wings. Large pods in each wing housed two new turbojet engines each where the original piston engine would have been mounted. Though Curtiss wasn’t the only early jet manufacturer to stick with straight wings—the North American B-45 Tornado took its maiden flight the same year as the Blackhawk—the the XP-87 came a year after Boeing, using captured German data, turned the aviation world on its ear with the swept wing B-47 Stratojet.

Once the prototype was completed, the Blackhawk was found to be severely overweight. Its range was limited by inadequate room for fuel storage, and its performance was hampered by woefully underpowered Westinghouse engines. Following taxi tests at the Curtiss factory in Ohio in October 1947, the Blackhawk was disassembled and shipped to Muroc, California for flight testing. Unfortunately, problems for the aircraft continued when it was damaged during shipping. Mishaps during taxi tests pushed the maiden flight back to March 1, 1948.

Once in the air, the big fighter demonstrated acceptable handling characteristics, but suffered from buffeting when it exceeded the rather pedestrian speed of 220 mph. Still, it seemed that the Blackhawk might turn around Curtiss’ string of bad luck (the Navy had canceled the XF15C the previous year). The Air Force signaled their intention to order 30 production F-87A fighters outfitted with more powerful General Electric J47 engines, as well as an additional 30 RF-87A reconnaissance variants. However, the Blackhawk was never able to overcome the buffeting problems, and the Air Force canceled the program before the second prototype was completed. Funds that would have gone towards the purchase of the XF-87 were earmarked for more modern all-weather interceptors, specifically the Northrop F-89 Scorpion. Both Blackhawks were subsequently scrapped.

With its cancelation, the Blackhawk became the last aircraft to bear the Curtiss nameplate, and Curtiss-Wright sold its airplane division to North American Aviation. The company that began with a single experimental airplane in 1909 ended its run with a single experimental airplane forty years later. However, the company that Glenn Curtiss started at the dawn of the aviation era continues to this day, though it no longer builds airplanes. The Curtiss-Wright Corporation now manufactures components for the aerospace and defense industries, as well as equipment for generating nuclear power.

Connecting Flights

For more stories about aviation, aviation history, and aviators, visit Wingspan. For more aircraft oddities, visit Planes You’ve (Probably) Never Heard Of.

Sources:

Jones, Lloyd. U.S. Fighters. Aero Publishers, Inc., 1975.

JoeBaugher.com

How the Wright Brothers Blew It by Phaedra Hise