Welcome to This Date in Aviation History, getting of you caught up on milestones, important historical events and people in aviation from January 22 through January 24.

January 23, 1951 – The first flight of the Douglas F4D-1 (F-6) Skyray. One of the more important spoils of war that the Allies captured from Germany at the end of WWII was a trove of aerodynamic data that had been collected by German scientists and, in many cases, the scientists themselves. Germany was on the forefront of innovative and even radical aircraft design, and the Allies were soon employing many of the German ideas in their own aircraft. Among the materials captured in Operation Paperclip was the work of Alexander Lippisch, who had done a significant amount of research into delta wings, specifically tailless delta designs.

In 1947, the US Navy issued a requirement for a new interceptor, one that could be launched from land bases and carriers at sea. The new interceptor would have to be very fast and have an excellent rate of climb, as it was intended to intercept bombers flying at 40,000 feet with a speed of 575 mph. With an interception range of 100 miles, the new fighter would have to reach 40,000 feet in just five minutes. Following the inspiration of Lippisch, famed Douglas engineer Ed Heinemann created a relatively small aircraft that had rounded delta wings and no tail. The wings were swept to 52.5 degrees, which had the added benefit of shifting the center of gravity aft, thereby improving the aircraft’s pivot point in pitch. With no horizontal tail, the pilot controlled pitch and roll with the use of elevons, a movable control surface that combines the functions of ailerons and elevators. This arrangement later became standard on most delta wing designs. A hydraulic booster helped activate the elevons and, in the event of hydraulic failure, the control stick could be extended by 12 inches to give the pilot more leverage to work them manually.

Heinemann originally planned to use the Westinghouse J40 afterburning turbojet, but that engine wasn’t ready in time for use in the prototype. So Douglas substituted a less powerful Allison engine, which significantly affected the Skyray’s performance. The only engine available at the time that would give the Skyray the required performance was the Pratt & Whitney J57, but using this engine required a complete redesign of the fuselage, which Douglas did. The extra work proved worthwhile, because the Skyray turned out to be everything the Navy wanted in an interceptor, and could easily have been nicknamed Skyrocket instead of Skyray (the unofficial nickname was Ford, for F4D). During a test flight on October 3, 1953, the Skyray established a world speed record of 753 mph, the first carrier-based aircraft to hold the title. And, in another test, a Marine Corps pilot took his Skyray to 50,000 feet in just 2 minutes 36 seconds, setting a world record for the fastest time to altitude.

The Skyray entered service in 1956 and a total of 422 were produced. However, despite the Skyray’s blistering speed, it soon became a victim of its own specialization. Designed solely as a high altitude interceptor, the Skyray was unsuited for the multi-role missions that newer, larger carrier aircraft were designed for. It served for only eight years before the Navy phased it out of service in 1964, though NACA continued to fly four Skyrays for research missions until 1969. In an effort to extend the life of the design, Douglas developed a larger, more powerful, multi-role version with the F5D Skylancer, but it was not adopted by the Navy, and only four were built.

January 23, 1939 – The first flight of the Douglas A-20 Havoc. The Douglas A-20 Havoc was arguably one of the best medium bombers of WWII, but it doesn’t garner nearly as much attention today as the North American B-25 Mitchell, its closest competitor, even though they both arose from the same 1937 US Army request for new attack aircraft. In response to the Army’s request, North American submitted their NA-40 (which would become the B-25), Douglas proposed their DB-7 (Douglas Bomber 7, which would become the A-20, and was designed by Ed Heinemann), Stearman submitted the X-100, and Martin proposed their 167F (which would become the Maryland). In the end, the Army chose North American’s offering, and showed little interest in the submission from Douglas. However, the French showed significant interest in the Douglas design, and they ordered 270 DB-7s at the outbreak of WWII with their own specific modifications. These included a thinner, taller fuselage, 1,000 hp Pratt & Whitney radial engines, French-made guns, and cockpit instruments that used the metric system. These aircraft took part in a vain attempt to stop the German invasion of France, and the survivors were evacuated to North Africa with the fall of France. In battle, the DB-7 proved to be rugged and dependable, with excellent maneuverability and speed for its size.

With the fall of France, the remaining aircraft were handed over to the British, where they became known as the Boston. The RAF intended them to be used as bombers; however, their range was not sufficient to reach targets on the European mainland, so many were instead converted to night fighters called the Havoc I. In this role, the glazed bombardier’s position was replaced with a solid nose which housed a targeting radar. It was also fitted with forward firing machine guns. Another version, called Turbinlite, was given a 2.7 million candlepower spotlight powered by batteries in the bomb bay along with a targeting radar. The unarmed Turbinlite aircraft illuminated enemy bombers bombers so they could be attacked by other aircraft. A large number of A-20B, G and H Havocs were exported to the Soviet Union through the Lend-Lease program, and the Russians eventually operated more Havocs than the United States. The Soviets appreciated the high speed and maneuverability of the big plane and, when fitted with more powerful machine guns and cannons, it became a potent tank buster for the Soviet Air Force. Havocs were also exported to the Netherlands and Australia, where they saw service in the Pacific Theater.

Though initially cool to the A-20, the US Army changed its mind after seeing how well the bomber served in French and British hands. The Army placed orders for two versions of the A-20: one for high-level bombing (A-20) and the other for low-level attack (A-20A). Douglas also produced a version known as the A-20B, which was intended for high-level bombing, with armor protection and self-sealing fuel tanks removed to reduce weight. Though the Army ordered 999 of these B models, the majority were sent to Russia. The A-20G, which removed the glazed nose in favor of four 2omm cannons and two .50 caliber machine guns, was the most highly produced model with 2,850 built. The G model proved particularly effective in the Pacific against Japanese ground targets and shipping.

When the US entered into WWII, their first purpose-built night fighter, the Northrop P-61 Black Widow, was still a year away from its maiden flight, and wouldn’t enter service until late in the war. Following the British lead, the Americans converted the Havoc to the night fighting role. Dubbed the P-70, the aircraft’s glazed nose was painted over and filled with a SCR-540 radar, which was a copy of the radar set used by the British. Four 20mm cannons were fitted in a tray beneath the bomb bay, and extra fuel was loaded in the upper bomb bay. Later conversions of C and G models moved the weapons to the nose and the radar set took its place in the bomb bay.

In the end, the bomber that had initially been turned down by the US Army Air Forces proved to be a rugged, dependable, and extremely flexible platform that saw service in all theaters of the war. By the end of production in September 1944, nearly 7,500 Havocs had been built, with a handful also constructed under license by Boeing. Havocs were retired from US Air Force service by 1949, but a number of surplus aircraft made their way into private hands, where they were flown as cargo haulers and executive transport.

Short Takeoff

January 22, 2003 – The final communication is made between Pioneer 10 and Earth. Pioneer 10 is an unmanned spacecraft that was launched on March 3, 1972 and designed to study Jupiter. The probe made its closest approach to Jupiter on December 3, 1973, then crossed the orbits of Saturn in 1976 and Uranus in 1979 before finally achieving exit velocity and leaving our solar system on March 31, 1997. After solar power to the radios and antenna had become too weak, NASA received Pioneer 10's final radio message on January 22, 2003, when the probe was 12 billion kilometers from Earth. Pioneer 10's final trajectory would take it in the direction of the star Aldebaran, about 68 light years away. At its current velocity, it will take Pioneer 10 more than 2 million years to reach Aldebaran.

January 22, 1992 – The launch of Space Shuttle Discovery on STS-42 carrying the first Canadian woman into space. Astronaut Roberta Bondar flew as part of an international crew that also carried the first German astronaut, Ulf Merbold, on his second trip into Earth orbit. A neurologist, Bondar started training to be an astronaut in 1984. During her eight-day Shuttle flight, she served as a Payload Specialist for the International Microgravity Laboratory Mission and performed experiments inside the Shuttles pressurized Spacelab. Following her Shuttle mission, Bondar worked for more than 10 years with NASA, leading an international research team to find ways to help humans recover from the weightlessness of space travel.

January 22, 1922 – The death of Elsa Andersson. The daughter of a farmer, Andersson aspired to be more than just a farmer’s wife. At age 24, she learned to fly and became Sweden’s first woman pilot. Following that achievement, Andersson traveled to Germany to learn how to parachute, and toured as a parachuting stunt performer, often diving head first out of the airplane and performing acrobatics during free fall. Her untimely death came in the third jump of the day at a show Askersund, Sweden. In front of 4,000 spectators, Andersson’s parachute malfunctioned and opened too close to the ground to slow her fall. Andersson was 25 years old.

January 23, 2007 – The first flight of the Lockheed Martin CATBird (Cooperative Avionics Test Bed), a highly modified Boeing 737-33o developed to test the avionics on the Lockheed Martin F-35 Lightning II. Lockheed purchased the 737 from Indonesian Airlines and began the process of converting the former airlinier in 1986. With a full-sized F-35 lightning nose section on the front of the aircraft, and canards that are the exact size and position relative to the nose as the actual F-35, the CATBird provides an economical way to test the Lightning’s suite of avionics, and can carry engineers and other testing equipment aloft in a flexible system for testing different components and configurations.

January 23, 1909 – The first flight of the Blériot XI. In the early days of aviation, flying across the English Channel seemed an almost insurmountable feat. The first pilot to make the journey successfully was Louis Blériot, flying a Blériot XI, a plane of his own design and construction. The flight made Blériot an instant celebrity, and his fame was an important factor in the success of his budding aircraft company. Produced in single and double seat configurations, the Blériot XI saw service in WWI, and was the aircraft of choice for many pioneering aviators who used it for racing and record-setting flights. Two restored Blériot XIs exist today, and they are considered the oldest flyable aircraft in the world.

January 24, 1975 – The first flight of the Eurocopter AS365 Dauphin, a multipurpose medium helicopter that is currently produced by Airbus Helicopters. Similar in many ways to the commercially unsuccessful Aérospatiale SA 360, the AS365 improves on the earlier design by adding a second engine and other upgraded components. The Dauphin was originally developed by Aérospatiale, but through a series of corporate mergers it was subsequently produced by Eurocopter, and finally Airbus. The Dauphin was introduced in 1978, serves both commercial and military operators, and remains in production after more than 40 years. More than 1,000 Dauphins have been produced to date.

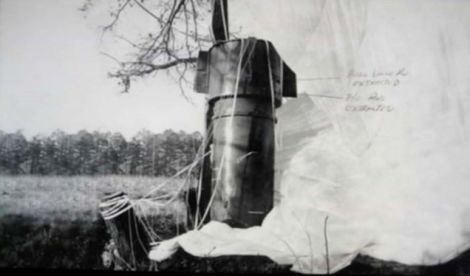

January 24, 1961 – A USAF Strategic Air Command bomber flying a 24-hour alert mission crashes while carrying two nuclear bombs. Known as the Goldsboro crash, the accident began when a Boeing B-52G Stratofortress based at Seymour Johnson AFB in North Carolina suffered a fuel leak from a ruptured wing. After flying out to sea to burn of fuel, the bomber was ordered to return to base. Unable to control the aircraft as it descended, the aircraft commander ordered the crew to eject, and the bomber eventually broke up, killing two crewmen, while a third died after ejecting. As the aircraft broke up, two Mark 39 nuclear bombs separated from the fuselage. One came down in a field and was destroyed. The second, though, parachuted to the ground as designed and landed upright, its parachute snagged on a tree. Of the four arming switches, three were tripped, meaning the bomb was one step away from detonating, though some experts dispute the claim that the weapon was close to detonating.

January 24, 1961 – The first flight of the Convair 990. In 1959, Convair became the last major manufacturer to enter the civilian jet airliner market with their 880, a four-engine, narrow-body airliner positioned to compete with the Boeing 707 and Douglas DC-8. However, the 880 was never able to capture much market share due to its smaller size, so Convair stretched the 880 by 10 feet to create the 990 Coronado. The new airliner could now seat up to 121 passengers, though still fewer than the 707. Unable to compete in passenger load, Convair bet that both the 880 and 990 would appeal to airlines due to their speed, which was about 40 mph faster than their competitors. However, the penalty for that speed was increased fuel burn. The 990 never caught on, and only 37 were built from 1961-1963. Despite its failure in the commercial market, the 990 remains the fastest non-supersonic airliner ever to enter production, having set a record of speed of Mach .97, or 675 mph, in 1961.

Connecting Flights

If you enjoy these Aviation History posts, please let me know in the comments. You can find more posts about aviation history, aviators, and aviation oddities at Wingspan.