Welcome to This Date in Aviation History, getting of you caught up on milestones, important historical events and people in aviation from February 1 through February 4.

February 1, 2003 – The loss of Space Shuttle Columbia. The Space Shuttle first launched into Earth orbit in 1981 and, over the course of 30 years of operation, Shuttles carried out 135 missions and spent almost 1,323 days in space. A total of 355 astronauts from 15 different countries traveled on board five different Shuttles throughout the program. Before the launch of Columbia, only one Shuttle, Challenger, had been lost, an accident that claimed the lives of seven astronauts, one of whom would have been the first teacher to fly in space. Though safety procedures were improved following the loss of Challenger, spaceflight remained an inherently dangerous undertaking, and the Shuttle program suffered another devastating loss 17 years after Challenger when Columbia broke apart during re-entry.

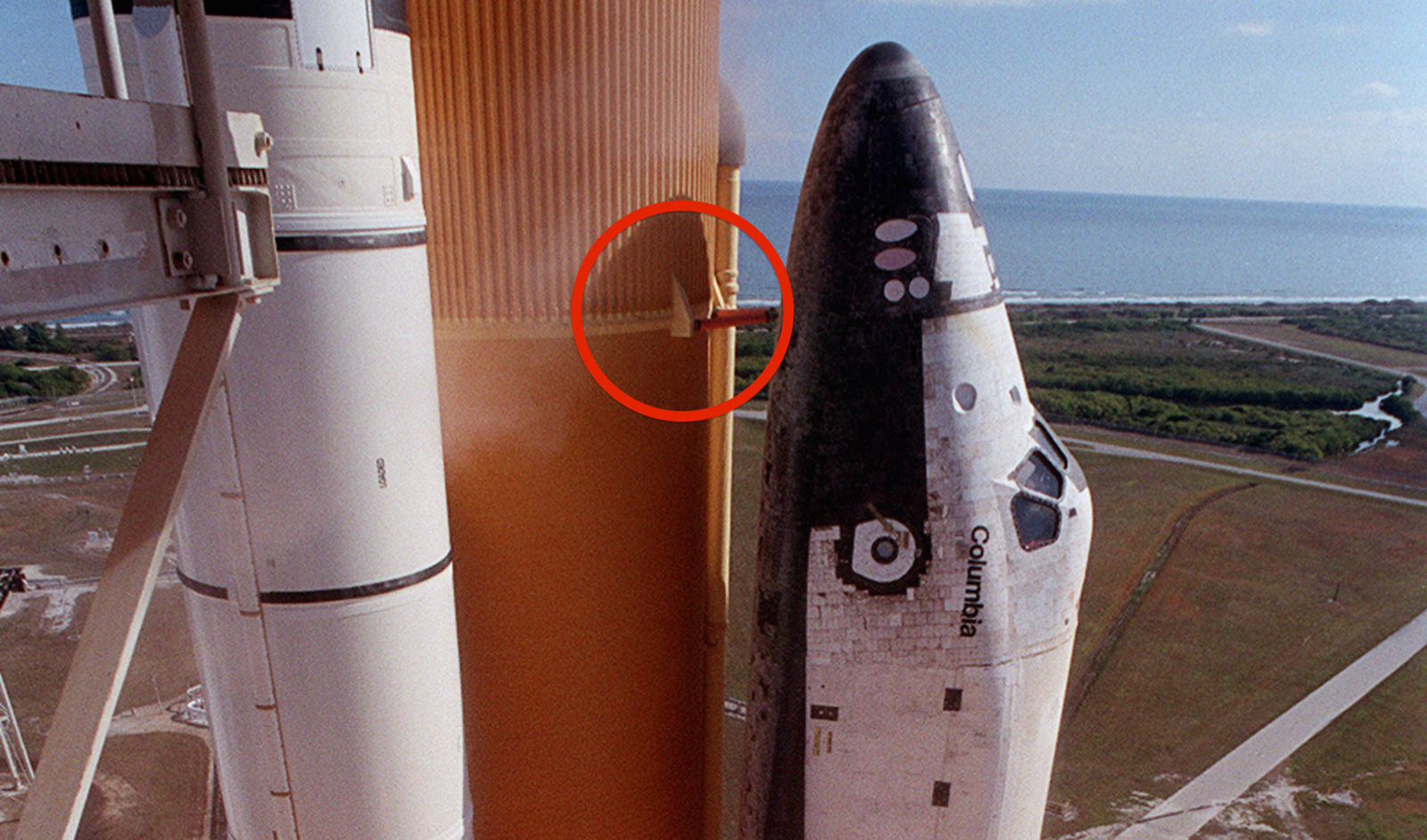

Space Shuttle Columbia launched on January 16, 2003 on STS-107, the 113th flight of the Space Shuttle program. When Shuttles blasted off, it was not uncommon for the extreme vibration caused by the firing of the main engines to dislodge pieces of the foam insulation that covered the external fuel tank. Some of the loosened insulation had struck the orbiter before, but in all previous launches the foam hadn’t caused significant damage to the vehicle. But when Columbia launched on that January morning, a large piece of insulation broke off from the external tank and struck the the orbiter, making a hole in the leading edge of the wing. It was not until Columbia was in orbit that a routine review of launch footage revealed the foam strike, but it was impossible to ascertain the extent of the damage. Shuttle engineers on the ground requested the Department of Defense to provide imagery of the Shuttle in orbit that might have shown damage to the orbiter, but for some reason, NASA managers blocked those requests.

It was also risky for the astronauts to assess the damage themselves. On this mission, Columbia did not carry the Canadarm remote manipulator arm, so assessing the wing would have required an unplanned spacewalk. And even then, had significant damage been discovered, the astronauts would have had to make a patch out of materials on hand, and there was no procedure for that, nor any assurance of success. Ultimately, NASA took the position that returning to Earth was the only option. They also decided that warning the astronauts would do no good, since there was nothing that the crew could have done to repair the damage.

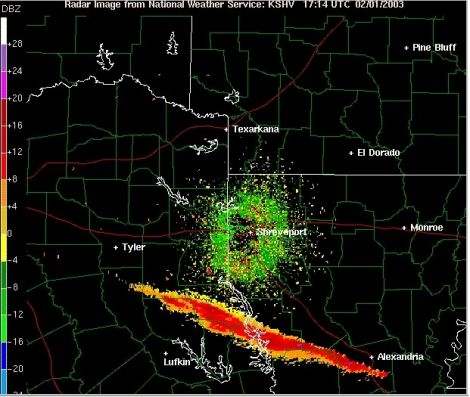

After completing its 15-day mission, Columbia and her crew began re-entry. As the Shuttle passed through the Earth’s atmosphere, the leading edges of the wings heated up to more than 2,800º F as the orbiter flew at more than 24 times the speed of sound. Superhot atmospheric gases entered the damaged wing, and the orbiter began to break up. Re-entry continued over Texas and Louisiana, when Columbia finally disintegrated, and pieces of the orbiter fell to the ground over a huge swath of east Texas and west Louisiana. Recovery teams also discovered parts of the astronaut’s bodies. But, even as the Shuttle was coming apart, the investigation found that pilot William McCool, a US Naval Aviator and test pilot, was starting up the Auxiliary Power Unit in a vain attempt to manually fly the Shuttle to a safe landing.

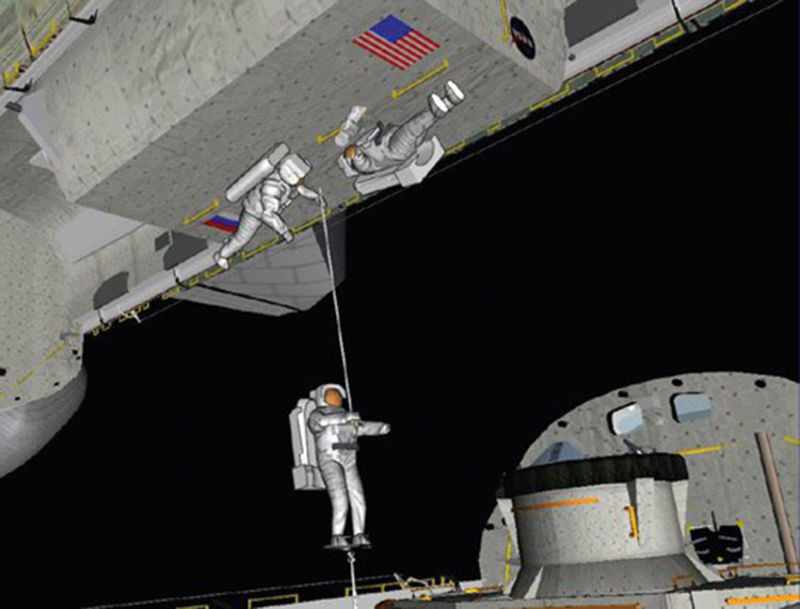

In the months following the disaster, investigators asked NASA engineers to report on other actions that might have been taken either to repair the Shuttle in orbit or for a rescue mission. The Shuttle Atlantis was being prepared for a launch to the International Space Station (ISS) in six week’s time, and it might have been possible to use that shuttle to rescue Columbia’s astronauts. But there were serious concerns about risking four more astronauts on a completely untried mission. Not only would Atlantis have to be prepped for launch in record time, the orbiter would have to rendezvous with Columbia, which had never been done before. Then the astronauts would been required to perform spacewalks between the orbiters to transfer from Columbia to Atlantis, since there was no way to dock the Shuttles. Two of Columbia’s astronauts had never performed a spacewalk. And all of this had to happen in less than 30 days, before Columbia’s food and water supply was exhausted. More importantly, Columbia’s supply of lithium hydroxide, which was used to scrub carbon monoxide from the air, would also run out. Despite the hypothetical possibility of rescue, the realities of such a dangerous mission almost certainly would have ruled it out.

Following the loss of Columbia, Shuttle missions were put on hold for two years, and construction of the IS was halted. The foam insulation on the external fuel tank was redesigned, and many of the large pieces that had been prone to breaking off in the past were removed. NASA instituted inspections of the Shuttle once it reached orbit, and a designated rescue mission was made ready in the event that severe damage was found. The final 22 Shuttle missions were flown only to the ISS so the crew could wait there for rescue if damage during launch rendered the orbiter unsafe for re-entry. Only one mission was undertaken that didn’t go to the ISS, a flight that made repairs to the Hubble Space Telescope.

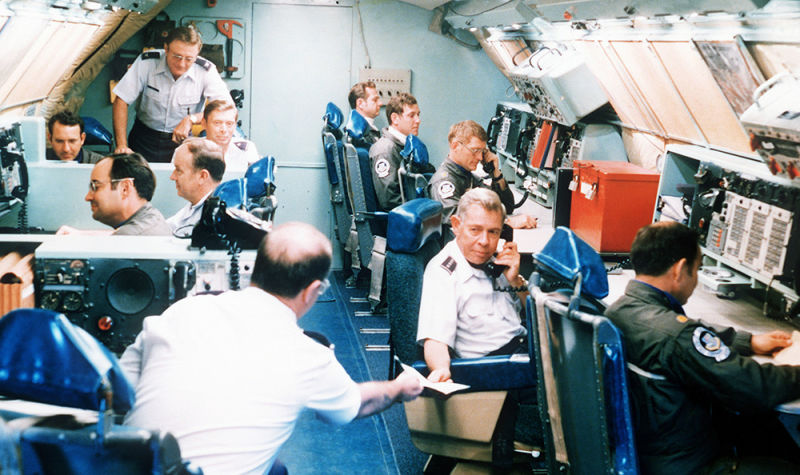

February 3, 1961 – The US Air Force Strategic Air Command commences Operation Looking Glass. During the Cold War, Russia and the US stood toe to toe in a conflict of differing cultural and political ideologies that left the world teetering on the brink of nuclear war. Though the doctrine of Mutual Assured Destruction meant that nuclear war would likely bring about armageddon, it was still imperative that any launch of nuclear weapons be detected early, so that a counterstrike could be loosed before the destruction of essential command and control facilities. But in the event that American ground control sites were destroyed, the US still maintained a system that would make a retaliatory strike possible, with the command to launch coming from an aircraft. In 1961, the US Air Force Strategic Air Command initiated Operation Looking Glass, which ensured that a command and control aircraft was in the air 24 hours a day, 365 day a year, and that the crew of that aircraft would be able to launch American missiles if ground-based crews had been incapacitated or killed.

The operation was named Looking Glass because the sentinel aircraft mirrored the capability of the ground based command structure. The Boeing EC-135, a highly modified version of the C-135 Stratolifter transport aircraft, had all the communications equipment necessary to contact US missile sites and to order a launch. If those sites were unable to respond, the missiles could be launched remotely from the air. The first of these round-the-clock flights took off on February 3, 1961, from Offutt Air Force Base in Nebraska. On board were two pilots, a refueling specialist, and approximately 20 other personnel to operate the communications equipment. But the most important person on those flights was a flag officer—either an Air Force general officer or a Navy admiral—who had the authority to order a launch of American missiles if the need arose. Looking Glass could also communicate with submerged nuclear submarines by extending a 2.5 mile long trailing wire antenna that broadcast via the Survivable Low Frequency Communications System. This allowed the officer on board the EC-135 to issue Emergency Action Messages to American submarines and order the launch of their missiles.

At Defcon 2 or higher, meaning that nuclear war was the next step, or that an attack was imminent, the Looking Glass pilots were required to wear an eye patch over one eye. If a nuclear explosion took place near enough to blind them with the flash, then they still had one good eye to fly the plane. Later, pilots were given special visors that instantly turned opaque in the event of a bright flash of light and then cleared.

Looking Glass flew continuously for more than 29 years, with only one 8-hour break in service. During that time, when no Looking Glass aircraft could take off from either Offutt AFB or Ellsworth AFB in South Dakota, the mission was covered by a Boeing E-4 Nightwatch aircraft. On July 24, 1990, Looking Glass ceased its continuous flights, but it remains on alert 24 hours a day should the need arise. In 1998, the EC-135 was retired in favor of the US Navy’s Boeing E-6B Mercury, a modified Boeing 707-320.

February 4, 1948 – The first flight of the Douglas D-558-2 Skyrocket. Following the first powered flight by the Wright Brothers in 1903, aircraft designers made incredible advances in a very short time, and perhaps the greatest impetus driving these aeronautical pioneers was the quest for ever greater speed. With the arrival of reliable jet engines during WWII, new jet-powered aircraft could outpace even the fastest propeller planes, and rocket planes pushed the boundaries speed even farther. The next barrier to break was the speed of sound, or Mach 1, and some believed that it could never be done. It was thought that an aircraft would simply be uncontrollable at such incredible speed. But once Chuck Yeager passed that milestone in 1947 flying the Bell X-1, the bar was raised once again. The next milestone to reach was Mach 2.

The Douglas D-558-2 Skyrocket was the second phase of a three-part Navy program to construct both jet- and rocket-powered aircraft to explore supersonic flight. The first stage in that program produced the D-558-1 Skystreak, a straight-winged, turbojet-powered research aircraft that first flew in 1947 and managed Mach 0.99, but could only exceed Mach 1 in a dive. Following discoveries on the benefits of swept wings, much of it gleaned from data captured from Germany at the end of the war, Douglas engineers went in a new direction with the D-588-2 Skyrocket. Unlike the Skystreak, the Skyrocket was much more aerodynamic, with 35-degree swept wings, swept tail, and a sharply pointed nose. At first, it was powered by a Westinghouse J34 turbojet, and the first flight tests were made using that engine configuration. The Skyrocket took off from the dry lake bed at Edwards Air Force Base assisted by rockets, and the experimental aircraft undertook numerous flights to test the Skyrocket’s flight characteristics in transonic and supersonic flight.

For the next phase of testing, the turbojet was removed and replaced with a Reaction Motors LR8-RM-6 liquid fueled rocket engine, the same engine that powered the X-1, and provided the Skyrocket with 6,000 lbf of static thrust. Unable to take off without its jet engine, the rocket-powered Skyrocket was carried aloft by a US Navy P2B, the Navy designation for the Boeing B-29, and a number of flights were taken that brought the Skyrocket very near Mach 2. These flights also set unofficial altitude records in the process (in order to achieve an official altitude record recognized by the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale, the aircraft must take off and land using its own power).

The pressure was now on to break the Mach 2 barrier, but the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA), which was running the tests, refused, saying that they were not in the business of setting records. However, NACA finally relented. For the record-setting flight, the Skyrocket was fitted with modified rocket nozzles and filled with chilled alcohol fuel so more propellant could be placed on board. The fuselage was then coated in wax to help reduce drag. After disengaging from the mothership, Navy test pilot Scott Crossfield flew the Skyrocket to 72,000 ft, then pushed over into a slight dive and reached Mach 2.005 (1,291 mph) on November 20, 1953. It was the one and only time that the Skyrocket exceeded Mach 2. All told, the three Skyrockets built by Douglas made 313 test flights throughout the program, and gathered significant data on swept wing flight in the transonic and supersonic regimes, data that would be vital in the design of the next generation of swept wing fighter aircraft.

Short Takeoff

February 1, 1987 – Budget airline People Express ceases operations. In an effort to take on the major US air carriers, People Express Airlines launched operations on April 30, 1981 with Boeing 737 flights from its hub at Newark Airport in New Jersey to Buffalo, Columbus, and Norfolk, with Jacksonville and Cleveland added the following month. Initially, all flights offered single-class seating, with ticket costing as little $149 one way, and lower fares charged at off-peak hours. Passengers paid for their tickets on board the plane following takeoff. As the airline grew, and larger aircraft such as the Boeing 747 were added to the fleet, higher priced business class seats were offered. People Express grew rapidly by acquiring other struggling airlines, and eventually served 41 domestic and international destinations. However, massive debt incurred during expansion put enormous financial strain on the airline, and it was taken over by Continental Airlines in 1986.

February 2, 2001 – The first flight of the General Atomics MQ-9 Reaper, a development of the earlier General Atomics MQ-1 Predator which had been designed only to perform aerial surveillance. With the Reaper, the US Air Force has the capability to perform both surveillance and attack missions either through remote piloting or autonomous flight. The Reaper is larger and heavier than the Predator, and can carry up to 2,400 pounds of external stores, including Hellfire air-to-ground missiles, GBU-12 Paveway laser guided bombs, and GBU-38 Joint Direct Attack Munition (JDAM). The Air Force is also testing the ability to carry Sidewinder air-to-air missiles. The Reaper has flown against targets in Iraq and Afghanistan, serves with NASA as a research aircraft (where it is called Altair), and with the Department of Homeland Security for border reconnaissance.

February 2, 1944 – The first flight of the Republic XP-72, an interceptor that was the ultimate development of the Republic P-47 Thunderbolt. The XP-72 was powered by a supercharged Pratt & Whitney R-4360 Wasp Major four-row radial engine, the same one that saw widespread use in large cargo aircraft and bombers. After the maiden flight was made with a standard four-bladed propeller, the XP-72 received a contra-rotating propeller which provided speeds of nearly 500 mph. The Army initially ordered 100 aircraft, but by this late stage in the war the US no longer needed a high-altitude interceptor. With the advent of jet-powered fighters on the horizon, the Army canceled the order after only two XP-72s prototypes were built.

February 3, 1998 – A US Marine Corps EA-6B Prowler cuts a gondola cable in Italy, killing 20 people. While flying through a canyon near the Italian town of Calavese during low-level flight training, the pilots of the Prowler flew below the “hard deck,” or the minimum altitude for safe operation, and struck the cable supporting a cable car. The cable car then plunged 260 ft to the ground, killing the 20 occupants. During the ensuing investigation, the pilots admitted that they flew at such a low altitude to “have fun” and to film the scenery, making a video which the pilot destroyed after returning to base. The crew was acquitted of involuntary manslaughter and negligent homicide, but were found guilty of obstruction of justice and conduct unbecoming an officer for the destruction of evidence, and were dismissed from the Marine Corps.

February 3, 1984 – The launch of Space Shuttle Challenger on STS-41-B, which carried out the first untethered spacewalk. STS-41-B was the fourth flight of the Shuttle Challenger and, while its main mission was the deployment of two communications satellites, the flight was notable for the first use of the Manned Maneuvering Unit (MMU), a device that fit over the astronaut’s life support backpack and propelled the astronaut using bursts of gaseous nitrogen. Mission Specialist Bruce McCandless II took the inaugural flight, followed by Mission Specialist Robert Stewart. The MMU was used on two subsequent flights before its retirement. A smaller system has since been developed, called the Simplified Aid for EVA Rescue (SAFER), but it is only intended for emergency use should an astronaut become untethered from the orbiter during extravehicular activity (EVA), more commonly referred to as a spacewalk.

February 3, 1964 – Operation Bongo II commences over Oklahoma City. With the advent of supersonic aircraft, and the possibility of regular supersonic transport over the United States, NASA, the FAA, and the US Air Force conducted Operation Bongo II to measure the effect of sonic booms on buildings, as well as public attitude towards repeated sonic booms. They also hoped to develop methods to predict the effect of the booms and to gather data for insurance companies. For a six-month period, a Convair B-58 Hustler flew 1,253 supersonic flights over Oklahoma City, averaging about seven sonic booms per day. Initially tolerant of the noise, residents soon began to resent the tests, and 147 windows were broken in the city’s tallest buildings. The negative publicity from the program, as well as the FAA’s botched handling of damage claims, were cited as part of the decision to cancel the Boeing 2707 supersonic airliner in 1971.

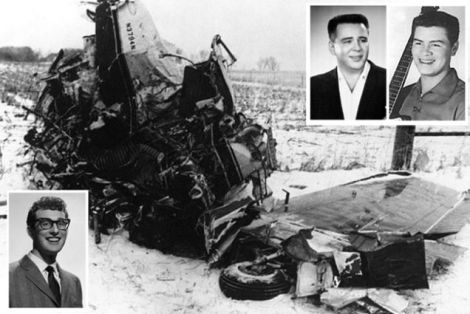

February 3, 1959 – A crash claims the life of Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, and J.P. “The Big Bopper” Richardson. Tired of riding in a cold tour bus, Holly chartered a Beechcraft Bonanza (N3794) to take himself, Valens and Richardson from Clear Lake, Iowa to Moorhead, Minnesota. The plane, piloted by Roger Peterson, took off at 12:55 am in snowy conditions with six mile visibility, though conditions were deteriorating rapidly. Peterson also was not given an accurate weather report, nor was he certified to fly in IFR conditions. He had also failed an instrument checkride nine months prior to the accident. The Bonanza was equipped with a Sperry altitude gyroscope rather than a traditional artificial horizon, and the two instruments read opposite of each other. Just five minutes after takeoff, and less than six miles from the airport, the plane crashed, killing all on board. The Civil Aeronautics Board stated the crash was caused by “the pilot’s unwise decision to embark on a flight” that required an IFR rating, but also listed the gyroscope, and the pilot’s lack of awareness of the worsening weather, as contributing factors.

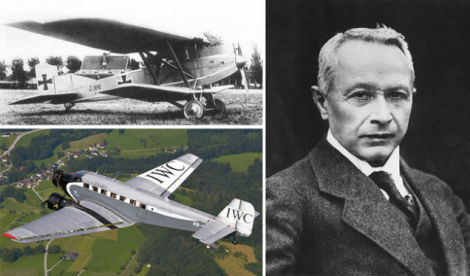

February 3, 1935 – The death of Hugo Junkers. Born on the same date in 1859, Junkers was a German engineer and aircraft designer who pioneered the development of all-metal airplanes in Germany. His company, Junkers Flugzeug und Motorenwerke AG, played a significant role in the development of the German aircraft industry between the World Wars, and Junkers created numerous all-metal aircraft for Germany during WWII while pioneering the use of duralumin in airplane construction. But perhaps his most far-reaching achievement was the Junkers Ju-52, a three-engine, corrugated metal passenger plane that helped create the business of civilian air travel. It served the Luftwaffe throughout WWII as a troop carrier and supply aircraft, and influenced other aircraft designs such as the Ford Trimotor. Although his company continued producing aircraft in his name for the Nazi war effort, Junkers had already been forced out of his company by 1934, and died the following year.

February 4, 2011 – The first flight of the Northrop Grumman X-47B, an unmanned combat air vehicle (UCAV) developed for carrier operations. The X-47B made its first launch from USS George H.W. Bush (CVN 77) on May 14, 2013, performed the first autonomous touch-and-go landings three days later, and made the first arrested carrier landing of a UCAV on July 10 of that year. The X-47B also demonstrated autonomous aerial refueling in April of 2015. Following the completion of the X-47 program, the Navy opened a competition for a deployable fleet of Unmanned Carrier-Launched Airborne Surveillance and Strike (UCLASS) aircraft in 2016, a program which then morphed into the Carrier-Based Aerial-Refueling System (CBARS) program that fielded the Boeing MQ-25 Stingray autonomous refueling aircraft in 2019.

February 4, 1946 – The first flight of the Republic XF-12 Rainbow. Designed by Alexander Kartveli, who also designed the P-47 Thunderbolt, the Rainbow was intended for use in the Pacific as a high-flying reconnaissance plane to find targets for allied bombers. The Rainbow was said to “fly on all fours,” which meant that it had four engines, a 4,000 mile range, could fly at 40,000 feet, and could cruise at 400 mph. It remains the fastest piston-powered aircraft of its size. Unfortunately for the Rainbow, it came at the same time as the emerging jet engine and, by the end of the WWII, the US no longer had a need for an aircraft of its type. Only two Rainbows were built before the project was canceled.

Connecting Fights

If you enjoy these Aviation History posts, please let me know in the comments. You can find more posts about aviation history, aviators, and aviation oddities at Wingspan.