Welcome to This Date in Aviation History, getting of you caught up on milestones, important historical events and people in aviation from March 7 through March 10.

March 8, 2014 – The disappearance of Malaysian Airlines Flight 370. The arrival of the airplane, and later the commercial airliner, made it possible for travelers to reach far flung corners of the globe, and geographical barriers such as mountain ranges and oceans no longer barred passage for voyagers. But flying over some of the more remote parts of the world is not without risk. In the earliest days of flight, it was not uncommon for an intrepid pilot trying to find the shortest route over a mountain, or trying to cross open water, to disappear without a trace. Hundreds of aircraft remain missing to this day, with no trace of either bodies or wreckage. In the days before satellites, cell phones, and radars, disappearances such as these could be accepted. But in our modern world of hyper-connectivity, it seems almost unfathomable that a huge airliner full of passengers could go missing without a trace or without explanation. But that is exactly what happened to Malaysian Airlines Flight 370.

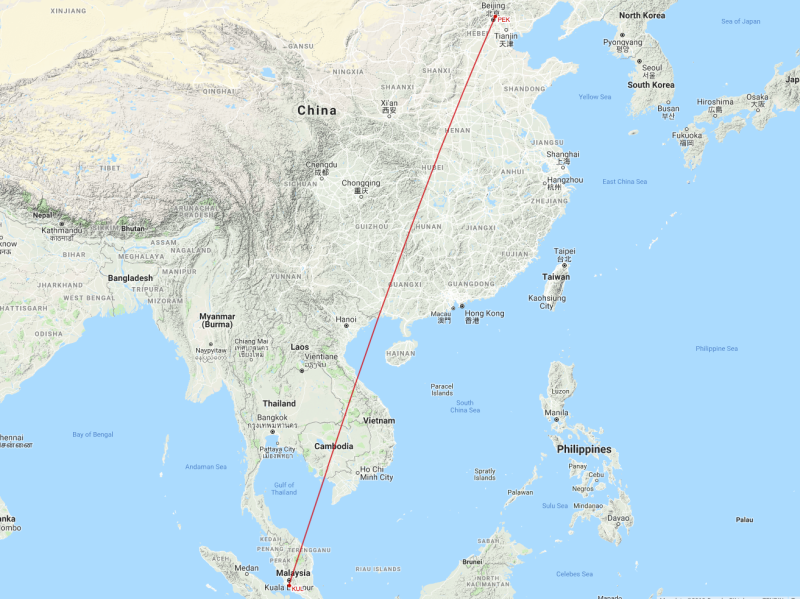

MH370 was regularly scheduled Boeing 777 (9M-MRO) service from Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia to Beijing, China. On board the flight were 12 Malaysian crew members and 277 passengers hailing from 14 different nations. Captain Zaharie Ahmad Shah, an experienced pilot with over 18,000 hours of flying time, was in command, with First Officer Fariq Abdul Hamid at his side. The scheduled flight time to Beijing was 5.5 hours, and the 777 carried fuel for 7.5 hours of flight, enough to fly a holding pattern or to safely divert should any troubles arise. MH370 took off on schedule at 00:42 local time and reached its planned cruising altitude of 35,000 feet. Thirty-eight minutes after takeoff, Captain Shah acknowledged instructions from the ground to contact Vietnamese air traffic controllers. It was the last time anybody was heard from onboard MH370.

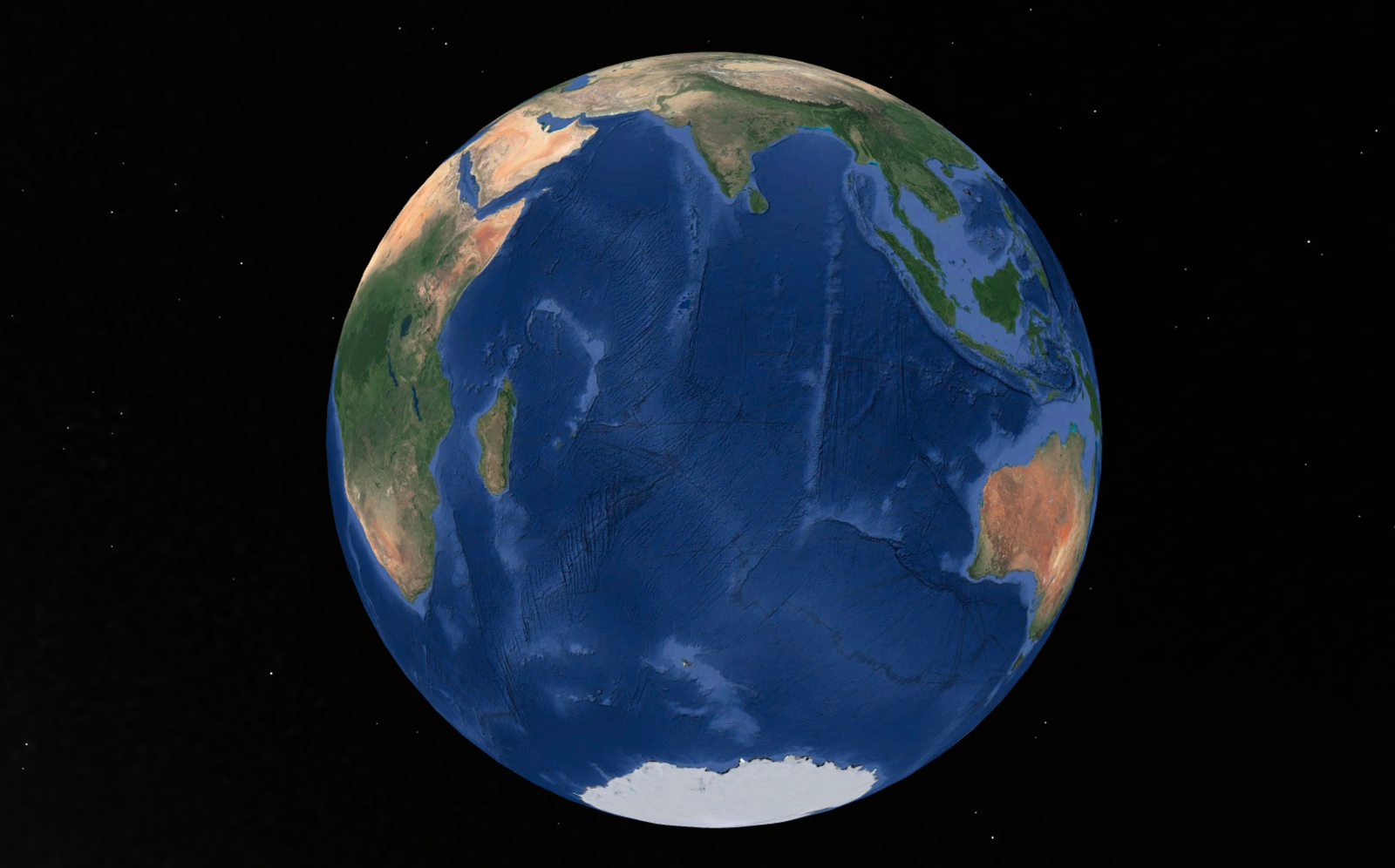

Two minutes later the Shah’s final transmission, the transponder stopped sending signals to the ground, and the aircraft, tracked by ground radar, changed course, headed westward back across Malaysia, and then out over the Adaman Sea. Military radar tracked the airliner as it headed toward the Nicobar Islands before all primary radar contact was lost. Though the transponder, which identifies an aircraft and its altitude, had presumably been turned off, and the airliner was out of range of land-based radars, that didn’t necessarily mean that the 777 was completely undetectable. The aircraft communications addressing and reporting system, or ACARS, a system which automatically sends various types of messages, such as when an aircraft takes off or lands, when the doors are opened, or when events happen with the engines, sent its final update at 1:06 local time before it was turned off. However, a second ACARS system, called Classic Aero, made continued hourly attempts to establish a connection to a satellite. While these attempts at contact didn’t provide specific positional information, they did allow searchers to determine the distance from the satellite, and thus calculate a likely path for the aircraft. One path was over land, while the other traced a course out over the southern Indian Ocean. These signals finally stopped 7.5 hours after takeoff, presumably when MH370 ran out of fuel and fell into the ocean.

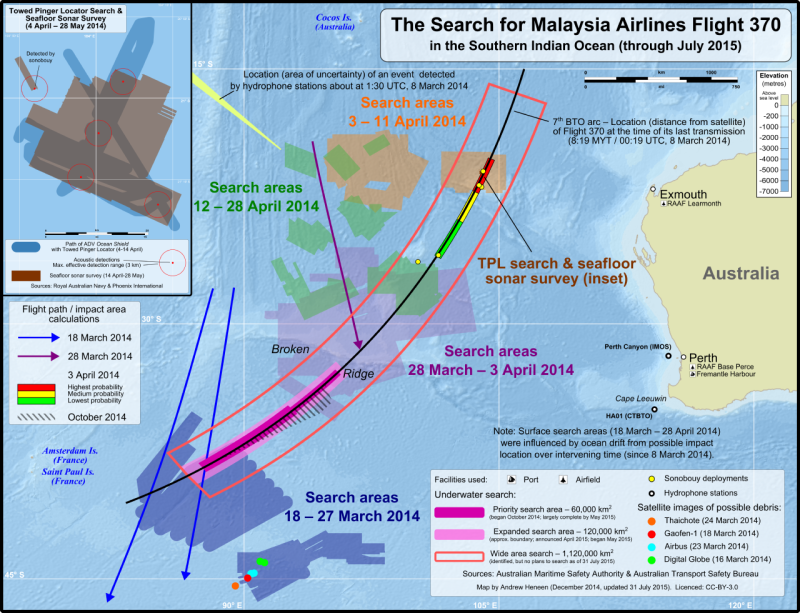

The search for the airliner initially focused on its last known location, but soon shifted to the waters west of Australia. In the most expensive search and rescue operation in history, 1.8 million square miles of the Indian Ocean were searched along the suspected flight path of MH370, yet not a single piece of debris was found, let alone any sizable wreckage. The flight data recorders had long since stopped sending locator signals, and any wreckage that sank could be as much as 15,000 feet under water. More than two years later, some pieces of wreckage, including a wing flap that was positively identified as belonging to MH370, washed up on beaches in the western Indian Ocean. But the bulk of the aircraft has yet to be found, despite another search mission that was started in January 2018.

With no wreckage to scrutinize and no flight data to analyze, investigators are left with only assumptions as to what happened to the flight. Two Iranian passengers, who were flying on one-way tickets using stolen passports, were later deemed to be refugees and not considered as possible terrorists. MH370 was also carrying a load of potentially dangerous lithium-ion batteries, but those were shown to have been packaged and loaded according to strict safety guidelines. Scrutiny then turned to Captain Shah. Though he did not show any motive for purposefully flying the plane into the ocean, American investigators did discover simulated flight paths that matched those of MH370's doomed flight on Shah’s home computer.

Even if the wreckage is eventually found, it still may not provide the final answers to the mystery of why the airliner flew so far off course and continued until its fuel was exhausted. Did the pilot purposefully reprogram the autopilot? Did a catastrophic event cause all on board to lose consciousness while the aircraft continued on its own? We may never know. New systems, such as the Global Aeronautical Distress and Safety System (GADSS) developed by the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), along with emerging data gathering technology called GlobalBeacon, which uses data provided by existing ADS-B equipment, will soon be able to update an aircraft’s position anywhere on the globe every minute. But until those new systems become operational, Malaysian Flight 370 will serve as a reminder that, no matter how small the world has become, it remains a vast place, and that no matter how connected we are, it is still possible to become utterly lost.

March 9-10, 1945 – The US Army Air Forces carries out Operation Meetinghouse, the first fire bombing raids on Japan. In the closing months of WWII, the strategy of island hopping had brought the United States and its allies within striking range of the Japanese home island. Flying from hastily built or captured airfields, American bombers steadily increased the number and magnitude of strategic bombing raids against Japanese manufacturing assets in an effort to destroy the production of war materiel and to demoralize the civilian population. However, unlike European countries, where manufacturing was generally centered in large factories and industrial areas, Japan’s war production was mostly carried out in small factories scattered around the country, and in homes as a cottage industry, where individual Japanese citizens manufactured munitions on a small scale. This dispersal of manufacturing assets rendered high altitude “precision” daylight bombing raids largely ineffective.

In 1944, US Army Air Forces General Curtis LeMay, a veteran of Eighth Air Force strategic bombing attacks against Germany, was transferred to the China Burma India theater and eventually took charge of all strategic bombing missions against Japan. A staunch advocate of strategic bombing, LeMay saw that American efforts were largely unsuccessful because Japanese cities were often covered in clouds, making accurate targeting more difficult if not impossible. Many of the bombs dropped from high altitude were blown off course by the jet stream, and deadly air defenses ruled out large scale low-level daylight raids. To increase the effectiveness of the bombing, LeMay advocated a switch to nighttime incendiary raids. Flown from as low as 5,000-8,000 feet, these fire missions did not require great accuracy, since fires started in the cities would do more damage than traditional high explosive bombs.

For the firebombing missions, Boeing B-29 Superfortresses were armed with M-69 incendiary bombs. A single M-69 munition weighed only six pounds, but they were dropped inside canisters that held 38 munitions each. Since air defenses were sparse by 1945, and antiaircraft artillery was less effective, all defensive armament was removed from the bombers to reduce weight and to increase the bomb load. Normally, each B-29 carried 37 canisters, totaling 1,400 individual incendiary munitions per aircraft. After they were dropped, the containers opened automatically and dispersed the smaller munitions, which ignited on contact with the ground and spread a jellied gasoline compound that was highly flammable. The Japanese capital city of Tokyo was chosen as the target for the first raid, codenamed Operation Meetinghouse.

On March 9, 1945, 346 B-29s left Guam and headed for the Japanese capital. Arriving over the city at 2:00 am on March 10 (Guam time), 279 bombers dropped almost 1,700 tons of incendiaries on a city built almost entirely of wood. The resulting fires destroyed 16 square miles of buildings, or 7% of the city’s urban area. The fires burned so fiercely that many people died from suffocation as the raging firestorm consumed all the oxygen. Following the raid, Tokyo police estimated that 83,793 people were killed, 41,000 injured and another 1 million left homeless. Postwar estimates place the toll as high as 100,000 killed. The USAAF lost 14 aircraft, below the 5% loss rate that was considered acceptable.

The firebombing raids continued in the belief that the attacks would force the Japanese government to capitulate. They did not. According to one estimate, the firebombing campaign caused the destruction of 180 square miles in 67 cities, and killed more than 300,000 people, a number that far exceeds the combined death toll of both the Hiroshima and Nagasaki atomic bombings. At the time, the US had few moral qualms about destroying such large civilian population centers. Military planners earnestly believed that these raids would shorten the war and save American lives by preventing a costly invasion of the Japanese home island. Though it was hoped that the atomic bombings of early August 1945 would finally compel the Japanese to surrender, no word was forthcoming from the Japanese government. Despite the horrors of the atomic bombs, two more firebombing raids were carried out before Japanese Emperor Hirohito finally announced Japan’s surrender on August 15, 1945, ending the Second World War.

March 10, 1959 – The first flight of the Northrop T-38 Talon. Following the birth of the jet fighter during WWII, development progressed at a rapid pace. But with that development came a trend towards increased complexity, greater size, heavier weight, and, perhaps most importantly, higher cost. In 1952, Northrop began work on a lightweight delta-winged fighter called the Fang, but the planned General Electric J79 engine alone would have weighed almost 4,000 pounds, and the program never progressed beyond preliminary drawings and a mock up. The following year, Northrop engineers learned of a new engine under development by General Electric that was intended for use in long-range missiles. The very small yet powerful General Electric J85 weighed a mere 600 pounds, yet it produced about 3,000 pounds of thrust, giving it the highest thrust-to-weight ratio of any engine in its class.

The Northrop design team, led by Edgar Schmued (the man who designed the North American P-51 Mustang), saw an opportunity to buck the trend in fighter design by building a small, simple, yet powerful fighter, with not one but two engines. Dubbed the N-156 by Northrop, the new fighter was initially developed for the US Navy, who planned to operate smaller fighters from the decks of escort carriers. However, the Navy sound dropped the idea of a small fighter when they decided to phase out the escort carrier. Undaunted, Northrop continued with development of their new fighter, now called the N-156F, spending their own money to do so. (The N156F eventually resurfaced as the F-5 Freedom Fighter, and won the International Fighter Aircraft competition in 1970.)

By the mid-1950s, the Air Force began looking for a two-seat, supersonic trainer to replace its aging fleet of Lockheed T-33s. In an example of perfect timing, Northrop modified the N-156 to create the N-156T trainer. Thus, where most two-seat trainers are developed from existing operational fighters, the T-38 trainer actually predates the F-5 fighter. Following the first flight of what was now called the YT-38 Talon, the Air Force quickly adopted the new trainer in 1961. The Talon went on to become the primary jet trainer for the US Air Force, and some estimates put the number of military pilots trained in the T-38 at more than 50,000. During an 11-year production run from 1961-1972, a total of 1,146 Talons were built.

The Talon continues to be the workhorse of the US Air Force Air Education and Training Command (AETC), preparing pilots for the McDonnell Douglas F-15C Eagle and F-15E Strike Eagle, the General Dynamics F-16 Fighting Falcon, Boeing B-52 Stratofortress, Rockwell B-1B Lancer, Northrop Grumman B-2 Spirit, Fairchild Republic A-10 Thunderbolt II, Lockheed Martin F-22 Raptor, and Lockheed Martin F-35 Lightning II. The T-38 was flown by the US Air Force Thunderbirds from 1974-1982 as a more fuel efficient and less expensive alternative to the McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom II during the OPEC oil embargo, and NASA operates a small fleet Talons for astronaut flight training and for use as a chase plane. The Talon has been in service for over 50 years, and the competition to built its replacement was won by the Boeing T-X in September 2018, with initial operational capability slated for 2024. Therefore, the Talon will be flying for a while longer. Only time will tell if the T-X will be able to match the capability and affordability and longevity of the venerable T-38.

Short Takeoff

March 7, 1975 – The first flight of the Yakovlev Yak-42, a medium-range trijet airliner and the first Soviet airliner to be powered by high-bypass turbofan engines. Developed from the Yakovlov Yak-40, the world’s first commuter trijet, the Yak-42 was primarily intended as a replacement for the Tupolev Tu-134, as well as other older turboprop-powered airliners. The airliner is powered by three Lotarev D-36 high bypass turbofans, has a cursing speed of 460 mph with a maximum range of 2,458 miles, and can accommodate up to 120 passengers. The Yak-24 entered service with Aeroflot in December 1980 and remains in service, flying primarily on routes out of Moscow, with international service to Helsinki and Prague. The Yak-42 was produced from 1979-2003, and a total of 140 were built.

March 7, 1964 – The first flight of the Hawker Siddeley Kestrel. Following the Hawker P.1127, the Kestrel was the second experimental aircraft developed to explore vertical/short take-off and landing (V/STOL) and ultimately led to the development of the Hawker Siddeley Harrier. Development of both the P.1227 and Kestrel began in 1957 following the introduction of the Rolls-Royce Pegasus vectored-thrust engine. The Kestrel (FGA.1) was an improved version of the P.1227, with fully swept wings, larger tail, and enlarged fuselage to accommodate the larger Pegasus 5 engine. Nine Kestrels were built and flown by the Tripartite Evaluation Squadron comprised of pilots from England, Germany and the United States (where it was known as the XV-6A), and it served as the prototype for pre-production Harriers.

March 7, 1945 – The first flight of the Piasecki HRP Rescuer, a tandem rotor helicopter designed by Frank Piasecki, who was a pioneer in the development of tandem rotor helicopters. To keep the two rotors from colliding, the rear of the fuselage curved upward, giving the Rescuer the nickname “Flying Banana.” It featured a tricycle landing gear, and the fuselage was built of steel tubing covered with doped fabric. The Rescuer was the first US military helicopter with the capacity for a significant number of passengers, and it served the US Navy, US Marine Corps, and US Coast Guard as a transport and cargo helicopter and for air-sea rescue. Piasecki built 28 Rescuers, and it was later developed into the H-21 Shawnee which served extensively in Korea and Vietnam.

March 8, 1954 – The first flight of the Sikorsky H-34. A development of the H-19 Chickasaw, the H-34 was originally designed by Sikorsky as an anti-submarine (ASW) platform for the US Navy. The H-34 was powered by a Wright R-1820 radial engine in the nose that drove the main rotor by a drive shaft that passed up through the cockpit and gave it a top speed of 173 mph and the capability to carry up to 18 troops or eight stretchers. The Army chose not to fly the H-34 in Vietnam, but the Marine Corps converted theirs into the first helicopter gunships by adding machine guns and rocket pods. The H-34 served the US until the mid-1960s, but also flew for numerous export countries around the world, as well as in a civilian version called the S-58. A total of 2,108 H-34/S-58s were built.

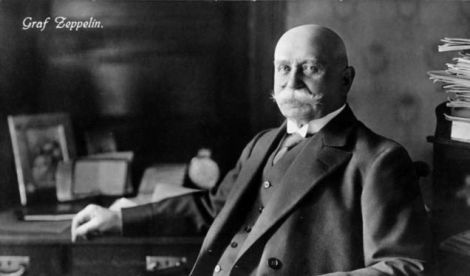

March 8, 1917 – The death of Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin. Count Zeppelin was born on July 8, 1838 in modern-day Baden Würtemberg and served as a general in the army of Würtemberg before turning his interest to aviation. During the American Civil War, Zeppelin traveled to the United States and observed the use of observation balloons in battle, then returned to Europe to develop first dirigibles and rigid airships. His first airship, LZ 1, took its maiden flight in July 1900, and he followed it with ever larger airships that would eventually be capable of transatlantic flight. Zeppelins were used in combat during WWI and for intercontinental air travel during the interwar period, but their heyday ended in 1937 with the crash of the Hindenburg (LZ 129) and the advent of transatlantic airliners.

March 8, 1910 – Raymonde de Laroche becomes the world’s first woman to earn a pilot license. Born in 1882, de Laroche decided to become a pilot after seeing Wilbur Wright perform a flying demonstration in 1908. The following year she convinced her friend and airplane manufacturer Charles Voisin to teach her to fly. Since Voisin’s aircraft had only one seat, her first flight was a solo covering some 300 yards. One year later, de Laroche received license #36 from the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale. She made numerous flying demonstrations around Europe and Egypt and, despite serious injuries she sustained in a crash, she returned to the air and was awarded the Aero-Club of France’s Femina Cup for a four-hour nonstop flight. She also set two altitude records for women pilots in 1919. De Laroche died on July 18, 1919 in a crash that also killed her co-pilot.

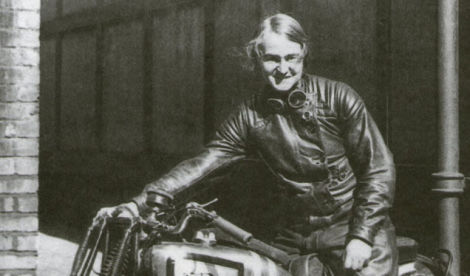

March 8, 1909 – The birth of Beatrice “Tilly” Shilling, a British aeronautical engineer, motorcycle racer, and auto racer. Shilling is best known for her invention of the R.A.E. Restrictor, known to pilots as “Miss Shilling’s Orifice,” which helped eliminate the problem of engine flooding in the early Rolls-Royce Merlin engines used on the Hawker Hurricane and Supermarine Spitfire. Following the war, Shilling worked on the Blue Streak missile and investigated the effects of wet runways on aircraft braking. As a racer, she was awarded the Gold Star for lapping the Brooklands circuit at an average of 106 mph on her Norton M30 motorcycle, and refused to marry her fiancé until he matched the feat and earned a Gold Star of his own. Shilling died on November 18, 1990 at age 81.

March 9, 2011 – Space Shuttle Discovery returns to Earth, marking the final mission of the first Space Shuttle to be retired by NASA. Discovery launched into space from the Kennedy Space Center for the last time on February 24, 2011, with a crew of six veteran astronauts on a mission to the International Space Station (ISS) to deliver the Permanent Multipurpose Module Leonardo, plus the humanoid robot Robonaut. The flight was the last of 39 missions spanning 27 years of service, more spaceflights than any other spacecraft to date. Discovery was the third orbiter to enter service after Columbia and Challenger, and made its maiden flight on August 20, 1984. All told, Discovery amassed more than a year in space. The retired orbiter is now on display at the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center near Washington, DC.

March 9, 1979 – The first flight of the Dassault Super Mirage 4000, a significantly larger and heavier development of the single-engine Mirage 2000. Unlike the 2000, the 4000 had two SNECMA M53-2 turbofan engines, as well as canards fitted above the air intakes. The Super Mirage was initiated as a private venture by Dassault and developed to compete with the McDonnell Douglas F-15 Eagle for export contracts. When Saudi Arabia chose to purchase the F-15, the Super Mirage project was canceled, but Dassault used much of the data gleaned from the 4000 program in the development of the Dassault Rafale. Only one Mirage 4000 was built, and it now resides at the Musée de l’Air et de l’Espace in Paris.

March 9, 1949 – The first flight of the Avro Shackleton. The Shackleton, named in honor of Irish explorer Sir Ernest Shackleton, was a long-range four-engine maritime patrol aircraft that traces its lineage back to the Avro Lincoln bomber, which itself was a development of the Avro Lancaster bomber of WWII. Following its introduction in 1951, the Shackleton served the Royal Air Force and South African Air Force and saw action with the RAF during the Suez Crisis in 1956. In addition to its maritime surveillance role, the Shackleton also served as a search and rescue platform, with one aircraft crew remaining on alert at all times should it be needed to respond to an emergency. A total of 185 Shackletons were built between 1951-1958, and it was retired from service in 1991.

March 10, 1978 – The first flight of the Dassault Mirage 2000. Based on the delta wing Mirage III, the Mirage 2000 was developed in the 1970s as a lightweight fighter to compete with the General Dynamics F-16 Fighting Falcon for the export market. Since the Mirage 2000 was based on an existing successful aircraft, the prototype was ready for its first flight in just 27 months.. The type entered service in November of 1982, and just over 600 examples were produced, with the majority sold to Dassault’s export customers. The 2000 saw service with the French during the Gulf War and in Afghanistan, and it remains in service today, though it is currently being phased out in favor of the Dassault Rafale.

March 10, 1966 – US Air Force Maj. Bernard “Bernie” Fisher earns the Congressional Medal of Honor. Fisher was leading a two-ship element of Douglas A-1 Skyradiers, part of six aircraft supporting US troops in the A Shau Valley in Vietnam. One of the Skyraiders, piloted by Maj. D.W. “Jump” Myers, was hit and forced to land on an airstrip belonging to South Vietnamese militia (CIDG) and US Special Forces that was under enemy attack at the time. With the closest rescue helicopter at least 3o minutes away, Fisher landed his Skyraider under heavy enemy fire and picked up the downed pilot. Dodging craters and debris on the runway, Fisher took off, his Skyraider riddled with holes from small arms fire. For his actions, Maj. Fisher was awarded the Medal of Honor, becoming the first member of the US Air Force to receive the decoration in the Vietnam War.

March 10, 1956 – Lt. Cdr. Peter Twiss, flying a Fairey Delta 2, becomes the first pilot to exceed 1,000 miles per hour. The Fairey Delta 2 was an experimental aircraft built to explore flight in the transonic and supersonic regimes. The delta-wing aircraft with a droop nose, an arrangement that would later be used on the supersonic Concorde airliner, took its maiden flight on October 6, 1945, and the two test aircraft made numerous supersonic flights, including supersonic flights without afterburner. Lt. Cdr. Twiss shattered the speed record held at the time by a North American F-100 Super Sabre when he flew at 1,132 mph, or Mach 1.73. The Delta 2 held the record for more than a year before it was broken by a McDonnell Douglas F-101 Voodoo. The two Delta 2 aircraft continued their testing duties, and and were retired in 1966 (WG777) and 1973 (WG774).

March 10, 1936 – The first flight of the Fairey Battle, a large, single-engine monoplane that was originally conceived as a replacement for older biplane bombers. Though it was powered by the same Rolls-Royce Merlin V-12 engine used in some of the most successful aircraft of WWII, it was severely hampered by its size and weight. The Battle proved to be a significant improvement over the biplanes it replaced; however, it was completely obsolete by the outbreak of WWII. In addition to its lack of speed and average handling, the Battle also lacked an armored cockpit and self-sealing fuel tanks, making it vulnerable to antiaircraft fire and Luftwaffe fighters. Nevertheless, Battles saw extensive, if somewhat futile, service in the early days of the war, but were withdrawn from frontline service by the end of 1941.

March 10, 1925 – The first flight of the Supermarine Southampton, one of the most successful flying boats of the period between the World Wars. The Southampton was developed from the earlier Supermarine Swan and was designed by R.J. Mitchell, who would later become famous for his design of the Supermarine Spitfire. Based on the success of the Swan, the Southampton was ordered into production straight from the drawing board, and a total of 83 were produced from 1924-1934. Following its delivery to the RAF in 1925, the Southampton took on its principal role of maritime reconnaissance. The Mark I was fitted with a pair of Napier Lion engines which gave it a top speed of 95 mph and a range of 544 miles, or a little more than six hours in the air, though later variants received a variety of powerplants.

Connecting Flights

If you enjoy these Aviation History posts, please let me know in the comments. You can find more posts about aviation history, aviators, and aviation oddities at Wingspan.