Welcome to This Date in Aviation History, getting of you caught up on milestones, important historical events and people in aviation from May 6 through May 8.

May 6, 1941 – The first flight of the Republic P-47 Thunderbolt. From its inception in WWI up until the middle of WWII, the single-engine fighter was, by design, a relatively small aircraft. Most aircraft designers and fighter pilots believed that a smaller, more maneuverable fighter would be more effective in a dogfight, and fighters such as the Mitsubishi A6M Zero, Supermarine Spitfire, and North American P-51 Mustang are some of the finest examples of this school of thought to emerge from the Second World War. So, when the enormous P-47 Thunderbolt arrived in England in late 1942, weighing in at 10,000 pounds (about 2,500 pounds more than a P-51, and fully twice the weight of a Spitfire), pilots were skeptical. But that skepticism was soon proven to be unfounded, and the rugged, hard-hitting Thunderbolt secured a place in the pantheon of the greatest fighters of the war. However, the P-47 didn’t start out as a huge aircraft.

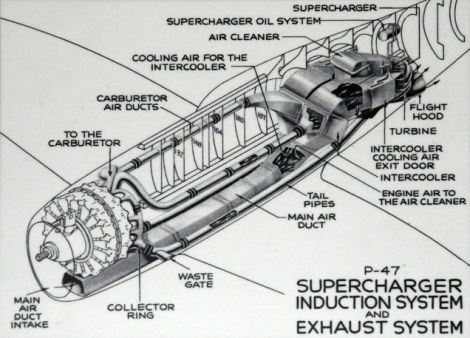

The Thunderbolt traces its roots back to 1939, when Republic Aviation proposed the development of a lightweight fighter, similar in size and capability to the Curtiss XP-46, which had been rejected by the US Army Air Corps. The Army wasn’t interested in Republic’s proposal either, so designer Alexander Kartveli went back to the drawing board. As he worked to redesign the fighter, it gradually got bigger and bigger as more guns were added to it. Republic’s proposal now called for two .50 caliber machine guns in the nose and eight .50 caliber guns in the wings, with power coming from an Allison V-12 engine turning a 10-foot diameter propeller. But, as development progressed, reports from the front lines in Europe indicated that even this aircraft would not be adequate for the Army’s needs. Kartveli now proposed a massive fighter that would be powered by a supercharged 18-cylinder Pratt & Whitney R-2800 Double Wasp radial engine, the same engine that was used in the Vought F4U Corsair and the same one that would power the forthcoming Grumman F6F Hellcat. In a nod to the importance of the supercharger for high-altitude performance, the layout of the engine and supercharger was actually developed first, and the airplane was built around it. The pilot sat on top of the main air intake duct, and the carburetor ducts were routed around the cockpit. The enormous supercharger was placed in the tail of the aircraft. This arrangement proved to be quite successful, as it tended to protect the vital supercharger from battle damage.

To pull the giant fighter through the air, the 10-foot diameter propeller of the P-47's predecessor gave way to a massive 12-foot diameter Curtiss Electric constant speed propeller (the Corsair’s was even larger, at 13 feet 4 inches). But having such a large prop meant that the landing gear needed to be long enough to keep the prop from striking the ground. Kartveli’s team solved that problem by creating a telescoping strut that extended by nine inches after it was lowered. Early models of the P-47 had a razorback canopy configuration, but pilots complained about poor visibility. To correct that shortcoming, the British fitted a P-47 with a plexiglass bubble canopy taken from a Hawker Typhoon, and soon all Thunderbolts were built with such a canopy. This became the definitive model through the rest of the war.

Nearly two years of testing followed the Thunderbolt’s first fight, and the P-47 flew its first combat missions in April of 1943. Pilots who were at first dubious of the mammoth fighter soon discovered that the Thunderbolt, or Jug as it came to be known, could out dive anything in the sky, and its rugged construction became legendary for bringing pilots home after suffering massive battle damage. The top American fighter ace over Europe in WWII, Francis “Gabby” Gabreski, scored 34.5 victories while flying a P-47. Although initially supplanted by the P-51 in the bomber escort mission, the P-47 eventually regained that role as continued development increased its range. Many Thunderbolts escorted bombers to the target and then dropped down near the ground on the return flight to destroy targets of opportunity along their path using machine guns, bombs, or rockets. By 1945, the Army still had nearly 6,000 P-47s on order, but those orders were canceled following VE Day. Nevertheless, more than 15,600 had already been built, just beating out the Mustang as the most-produced American fighter in history. Passed over for service in Korea, the Jug was retired in 1955, though some remained in service for another 11 years with the Peruvian Air Force.

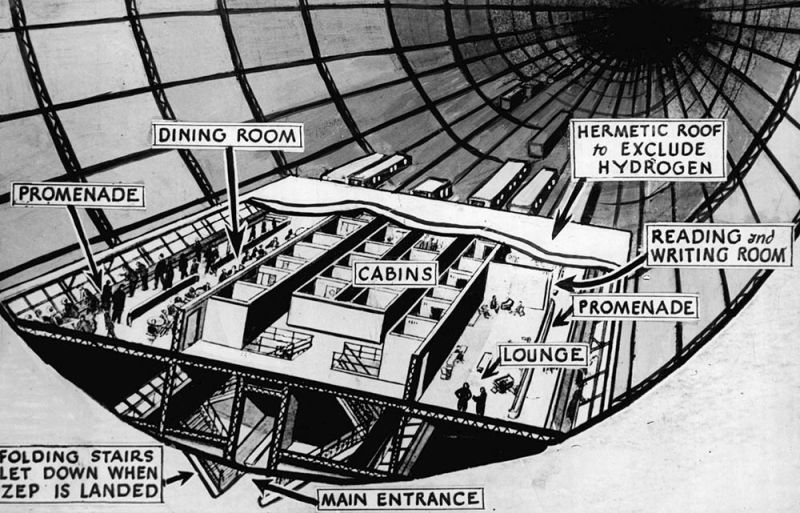

May 6, 1937 – The German Zeppelin Hindenburg crashes while attempting to land following a flight to the United States. Before nonstop transatlantic airliners entered service around 1940, flying passengers across the Atlantic Ocean was the the bailiwick of the rigid airship. During the 1920s and 1930s, these “ocean liners of the sky” grew ever larger, and culminated in the Hindenburg and Graf Zeppelin II, the largest aircraft that ever took to the skies. Hindenburg, German dirigible LZ-129 (Luftschiff Zeppelin #129, registration D-LZ129) was a rigid airship and the lead ship of the Hindenburg class. Designed and built by the Zeppelin Company (Luftschiffbau Zeppelin GmbH), Hindenburg, named after the late Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg, President of Germany from 1925-1934, was constructed of a duralumin framework fitted with 16 cotton gas bags. The outer skin of the airship was made of cotton fabric covered with a reflective coating meant to protect the gas bags from ultraviolet and infrared radiation. Power for the Hindenburg came from four 16-cylinder Daimler-Benz DB 602 diesel engines which produced 1,200 hp each and gave the airship a top speed of 85 mph.

Hindenburg was originally built to be filled with helium, but helium was rare and came at an exorbitant cost. Construction of Hindenburg went ahead regardless, even though the designers knew they would have trouble obtaining the lifting gas from the United States, the world’s primary supplier of helium, where it was a byproduct of natural gas mining. When the US refused to lift the export ban on helium, Hindenburg’s designers made the fateful decision to switch to highly flammable hydrogen instead. Hindenburg took its maiden flight on March 4, 1936, and the airship completed its first crossing of the Atlantic on May 6, 1936. It was the first of seventeen transatlantic flights and set a record for the time when it completed the trip in 64 hours, 40 minutes. Eastward transatlantic flights, with help from prevailing winds, averaged around 55 hours. Not only did these transatlantic crossings shave significant time off the ocean liners of the era, they also had the added advantage of being able to operate from inland bases.

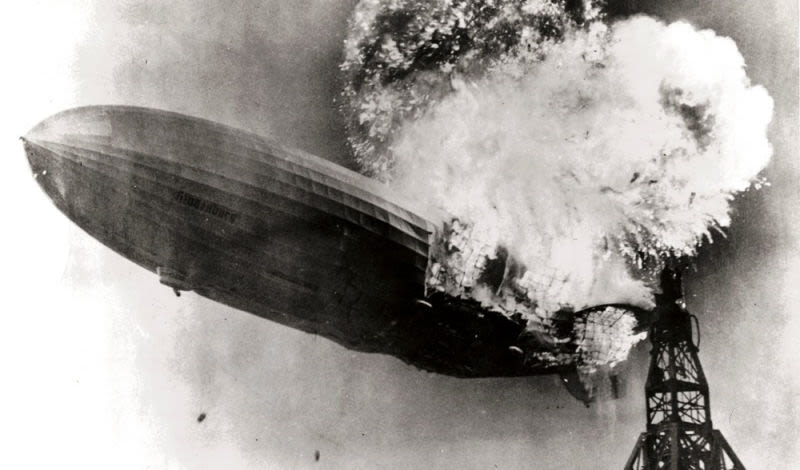

On May 3, 1937, Hindenburg departed Frankfurt for a transatlantic crossing to Lakehurst, New Jersey. Slowed by strong headwinds, the airship arrived over New Jersey on May 7, but the landing was delayed by a line of thunderstorms. Hindenburg was finally cleared to land at about 7:00 pm. At 7:21 pm, shortly after dropping mooring lines to the ground crew, Hindenburg suddenly burst into flames and crashed next to the mooring mast. Within thirty seconds, the Zeppelin was reduced to a smoldering wreck of twisted, charred metal. Thirty-five passengers and crew died in the crash and flames, and one person on the ground was killed.

The cause of the explosion and crash has been the topic of much debate and remains a mystery to this day. Some suspect sabotage, while others believe that atmospheric conditions could have played a role in the explosion and fire. One of the more plausible theories is that static electricity ignited hydrogen gas that was leaking from one of the cells. During Hindenburg’s landing, witnesses reported seeing large amounts of water ballast being dumped, which could indicate a significant leak of hydrogen that was causing the airship to descend more rapidly than normal. After the crash, the duralumin hulk was returned to Germany where it was recycled for use in the construction of Luftwaffe aircraft. The crash of Hindenburg effectively signaled the end of transatlantic Zeppelin transport, despite a long list of passengers who were still willing to cross the ocean in an airship. With WWII under way in Europe, Graf Zeppelin II was scrapped in 1940 while still under construction, and its duralumin also went to support the German war effort.

Short Takeoff

May 6, 2006 – The US Air Force retires the Hanoi Taxi, the last Lockheed C-141 Starlifter. The Starlifter was a strategic airlifter that entered service with the Air Force in 1965 and was used extensively during the Vietnam War. Starlifter serial number 66-0177, known as the Hanoi Taxi, made history as the aircraft that brought home the first American prisoners of war released by Vietnam as part of Operation Homecoming in 1973. After the war, the Hanoi Taxi continued its regular airlift duties, and aided in the evacuation of victims of Hurricane Katrina in 2005. With the scheduled retirement of the final eight Starlifters, veterans and former POWs were given the opportunity to fly in the Hanoi Taxi once more. On its arrival at Wright-Patterson AFB, the aircraft was enshrined into the National Museum of the United States Air Force in Dayton, Ohio.

May 6, 1942 – The first flight of the Kawanishi N1K Kyōfū, a floatplane fighter developed for the Imperial Japanese Navy during WWII. When the floatplane version turned out to be ineffective, the N1K was further developed into the N1K-J Shiden, a land-based fighter known to the Allies as George, and proved to be one of the most effective Japanese fighters of the war. The Shiden was heavily armed and highly maneuverable, and was equipped with a mercury switch that automatically extended the flaps, helping to decrease the turning radius during a dogfight. In battle, the Shiden proved a match for the best Allied fighters, but came too late in the war, and in insufficient numbers, to make a significant contribution to the Japanese war effort.

May 6, 1935 – The first flight of the Curtiss P-36 Hawk. A contemporary of the Hawker Hurricane and Messerschmitt Bf 109, the P-36, also known as the Hawk Model 75, was an early example of the new generation of all-metal cantilever monoplane fighters. Introduced in 1938, the Hawk saw little service in WWII with the US Army Air Corps, but found great success as an export fighter, serving notably with the French during the Battle of France. The P-36 is perhaps best known as the predecessor to its much more famous descendant, the P-40 Warhawk. Only 215 Hawks were built for the US Army Air Corps, but 900 were exported to international customers. The last Hawks were retired by the Argentine Air Force in 1954.

May 6, 1930 – The first flight of the Boeing Monomail, so named because of it monoplane design and its intended function as a mail plane. The Monomail was an important development not only for its monoplane design but also for its all-metal construction, and featured a streamlined fuselage with fully-retractable landing gear. Eventually stretched to carry six passengers, the Monomail suffered from an underpowered engine and the lack of a variable-pitch propeller, and was soon surpassed by more modern designs. However, many of the technological advances made with the Monomail found their way into later Boeing designs, notably the YB-9 bomber and the P-26 Peashooter.

May 7, 1992 – The first flight of the Space Shuttle Endeavour, the sixth and final Space Shuttle constructed and the fifth flown into space by NASA (Enterprise, the first shuttle, was used for static testing and glide tests). Construction of Endeavour began in 1987 as a replacement to the Space Shuttle Challenger which was lost along with its crew in 1986. The Shuttle was named for British explorer Capt. James Cook’s HMS Endeavour (hence the British spelling), and it accomplished a number of firsts, including carrying the first African American woman astronaut to space, Mae Jemison, and completing the first mission to repair the Hubble Space Telescope. Following its first flight in 1992 on STS-49, Endeavour served until 2011, and flew a total of 25 missions before its retirement following STS-134. The orbiter is now on display at the California Science Center in Los Angeles.

May 7, 1946 – The first flight of the Handley Page Hastings, a British troop transport and general cargo plane that served the Royal Air Force as a replacement for the Avro York. The Hastings was powered by four Bristol Hercules radial engines and was capable of carrying either 50 troops, 35 paratroops, 32 stretchers, or 20,000 pounds of cargo. The Hastings first saw service as part of the Berlin Airlift in 1948, where it was used primarily to deliver coal to the blockaded city. The Hastings also served during the Suez Crisis in 1956, and was finally retired in 1977 and replaced in RAF service by the Lockheed C-130 Hercules. A total of 151 Hastings were produced from 1947-1952.

May 7, 1944 – The first flight of the Beechcraft XA-38 Grizzly, a twin-engine ground attack aircraft developed by Beechcraft for Operation Downfall, the planned invasion of Japan. The US Army Air Forces was looking for a replacement for the Douglas A-20 Havoc that would be capable of destroying bunkers or other hardened targets. The Grizzly was armed with a 75mm cannon in the nose, along with two forward-firing .50 caliber machine guns. Though the Grizzly showed promise, the Boeing B-29 Superfortress took priority in the allocation of Wright R-3350 Duplex Cyclone engines, and the Grizzly never entered production. Only two were built, with one scrapped and the whereabouts of the other unknown.

May 8, 2004 – The death of William J. “Pete” Knight. Knight was born in Noblesville, Indiana on November 18, 1929, joined the US Air Force in 1951, and served as a test pilot at Edwards Air Force Base flying the F-100 Super Sabre, F-101 Voodoo, F-104 Starfighter, T-38 Talon and F-5 Freedom Fighter. Following the cancelation of the Boeing X-20 Dyna-Soar project, Knight was selected to fly the hypersonic North American X-15. On October 3, 1967, Knight piloted the X-15 to a speed of Mach 6.72 (4,520 mph), setting an absolute speed record for manned flight that still stands. He was also one of five pilots to earn astronaut wings when he reached an altitude of 280,550 feet while flying the X-1. After his stint as a test pilot, Knight flew 253 combat missions during the Vietnam War, and retired from the Air Force in 1982 before serving as a California state politician.

Connecting Flights

If you enjoy these Aviation History posts, please let me know in the comments. You can find more posts about aviation history, aviators, and aviation oddities at Wingspan.