Welcome to This Date in Aviation History, getting of you caught up on milestones, important historical events and people in aviation from May 16 through May 19.

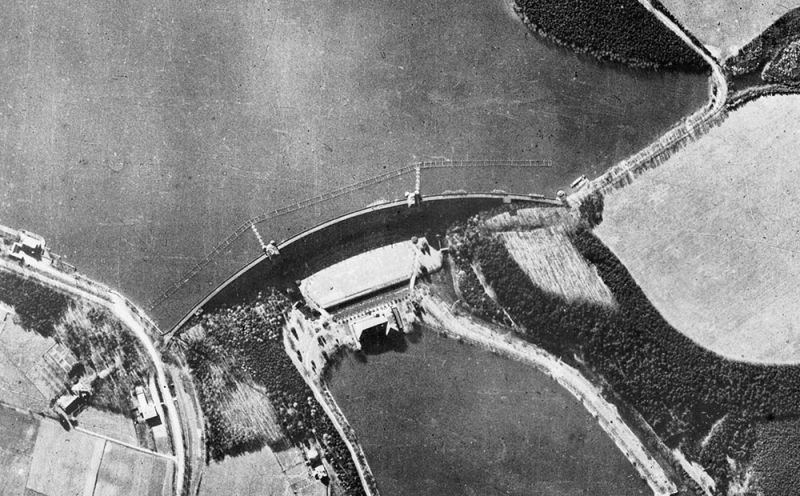

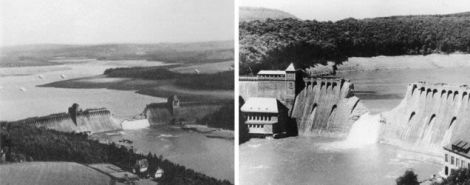

May 16-17, 1943 – RAF bombers carry out Operation Chastise. The River Ruhr traces a meandering course through western Germany from the mountainous Sauerland region down to the River Rhine. For centuries, the Ruhr had been the center of farming and industry. During the early to mid twentieth century, the Ruhr valley was the primary location for much of Germany’s manufacturing, as the river provided both pure water for the manufacture of steel and the generation of hydroelectric power via the Möhne and Sorpe Dams. The River Eder also flowed through this strategic region, and along with the Möhne and Sorpe, the Edersee Dam played a vital role in German manufacturing and farm irrigation.

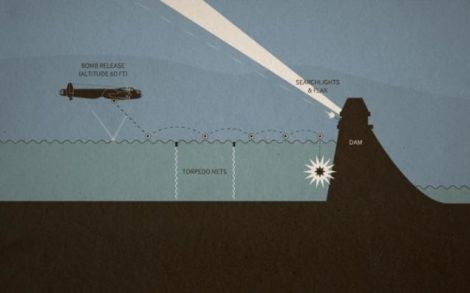

Even before the outbreak of WWII, the British Air Ministry identified these dams, and others like them, as potential strategic targets that could be destroyed should war break out with Germany, as they predicted it might. Breaching the dams would not only drain supplies of water for manufacturing and cut hydroelectric power, but the British also hoped that catastrophic flooding would damage factories, destroy rail lines, and hinder transport on inland waterways. But once the decision to destroy the dams was taken, the RAF was faced with a singular problem: How to do it? A torpedo wouldn’t work, since the dams were protected by multiple torpedo nets. Traditional bombing might eventually break down the dams, but it would take tons and tons of bombs, or perhaps one huge bomb, but there was no aircraft capable of carrying such a bomb, nor did the RAF possess the level of accuracy required to drop just one bomb, no matter the size.

Needing an entirely novel approach, the RAF turned to Barnes Wallis. Wallis was the Assistant Chief Designer at Vickers and had been working on a bouncing bomb concept that he originally proposed for use against shipping. But it soon became clear that such a weapon could also be used against dams. In order to breach the dam, the canister-shaped bomb, codenamed Upkeep, would have to be dropped from a precise level above the water, at a precise distance from the dam. It would also have to be rotating backwards at 500 rpm. Once the bomb was released, it would skip across the surface of the water, bounce over the torpedo nets, and settle to the base of the dam, where its detonation would be triggered by a hydroelectric fuse. While the bomb itself was fairly complex, the targeting system was anything but. To determine the correct distance from the dam for dropping the bomb, a simple sight with two prongs was used. As the bomber approached the dam, the prongs lined up with towers on the damn which indicated the correct distance. For altitude, one spotlight was fitted to the front of the bomber, and another aft, pointing downwards. When the circles of light joined on the surface of the water, the bomber was at the correct altitude.

On the night of May 16, a small armada of 19 specially modified Avro Lancaster bombers set out for Germany. However, the bombers began having trouble almost immediately. Some returned to base, while others were lost to enemy flak or crashed into antennas or power pylons. But the remaining planes forged ahead, and the Möhne Dam was the first to be hit and breached, followed by the Eder Dam. The Sorpe Dam, which was an earthen dam with a concrete core, was not breached, nor was the Ennepe Dam. On the return flight, two more Lancasters were lost, bringing the total to eight aircraft shot down and 53 airmen killed. Though the dams were breached and caused catastrophic flooding downstream, the Germans recovered quickly, and the hoped-for interruption of manufacturing and transportation did not materialize. In all, 1,600 were killed, but 1,000 of those were Russian prisoners and forced laborers working in the fields below the dams. And though factories were damaged and power was interrupted, water and electricity supplies returned to normal in just one month’s time. However, the raids did have the strategic result of keeping the Luftwaffe occupied protecting other infrastructure targets, and the development of extremely large bombs continued, resulting in the Tallboy and Grand Slam“earthquake bombs” which were used with great effect against hardened German targets later in the war.

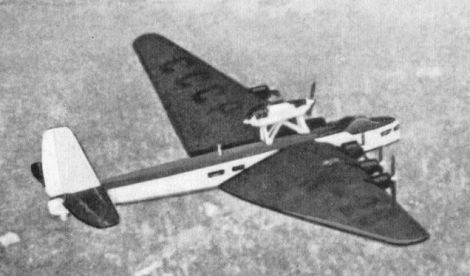

May 17, 1943 – The crew of the Memphis Belle completes its 25th and final mission. In 1935, Boeing flew their new, four-engined bomber, which they called the Model 299, for the first time. The bomber bristled with five .30 caliber defensive machine guns, so many for its day that a reporter for the Seattle Times described it as Boeing’s new “Flying Fortress,” because surely, this new bomber would be impervious to enemy attack. Boeing liked the name, trademarked it, and the legendary Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress was born. In practice, however, the Flying Fortress was anything but impregnable. B-17s of the 8th Air Force began bombing missions into German-occupied Europe in 1942, but even though the defensive armament had increased to 10 machine guns, or more, the lack of escort fighters to protect the lumbering bombers meant that they were easy prey for German fighters and sitting ducks for highly accurate flak (flak is an acronym for Fliegerabwehrkanone, or anti-aircraft artillery). Add to that the fact that the American bombers flew their missions during daylight hours to increase accuracy, and the Flying Fortress began to suffer horrible losses of planes and crews. In October 1943 alone, the 8th Air Force lost 176 bombers, more than five per day.

The aircrews, made up mostly of boys barely 18 years old and pilots who were only in their 20s, were expected to fly 25 missions to complete their tour. However, with an average loss rate of 8-percent of the bombers per mission at that time, the odds were very poor that a single crew would fly all of their missions and return safely without the loss of even one man. Throughout the war, the number of missions needed to complete a tour fluctuated depending on need and risk assessment, sometimes going as high as 35. This was still an arbitrary number, but it gave the crews something to look forward to, a light at the end of a tunnel filled with fighters and flak that just might be attainable. Still, over 3,000 B-17s were lost in the war, and though the advent of long-range escort fighters in the second half of the war helped fend off the German attackers, flak always took its toll.

Despite the terrible odds, there were bombers and crews that managed to complete their tour, and one that did so famously (though not first—see author’s note below), was Memphis Belle, a B-17F (serial number 41-24485) assigned to the 324th Bombardment Squadron (Heavy), 91st Bombardment Group and commanded by Captain Robert Morgan. Based in Bassingbourn, Scotland, Memphis Belle and her crew carried out their first mission on November 7, 1942 against targets in Brest, France, and flew the majority of their missions over Brittany, with some missions to the Netherlands and a handful into Germany. Throughout its tour, Belle was shot up numerous times by fighters and punctured by flak. She went through nine engines, had both wings replaced, had the tail replaced twice, and both landing gear assemblies were replaced. But her luck held and, as Belle’s 25th mission approached, the US Army Air Corps saw an opportunity to generate some positive news for the home front.

The Army dispatched a film crew, led by famous director and producer William Wyler, to make a full-color documentary of the final flight titled Memphis Belle: The Story of a Flying Fortress, which was released to the American public in 1944.* After the final mission, Memphis Belle and her crew returned to the US, where they toured the country to help sell war bonds and to boost the nation’s morale. Following the war, the crew returned to life in the US, and the final member of the crew, top turret gunner Harold Loch, passed away in October 2004. Soon after the war ended in 1945, Memphis Belle was rescued from the scrap yard and purchased by the City of Memphis for $350. She was flown to Memphis and placed on display outdoors into the 1980s, where the bomber slowly deteriorated while being stripped of almost all her internal components by souvenir hunters. Finally, in 2004, the aircraft was transferred to National Museum of the United States Air Force in Dayton, Ohio, where it underwent a full restoration. It features prominently in a new WWII exhibit, and was unveiled to the public on March 17, 2018, 75 years to the day after her final mission. Hollywood also produced a dramatic film about the plane and her crew, The Memphis Belle, which was released in 1990.

Author’s note: The Memphis Belle and her crew garnered much notoriety for the completion of 25 missions, due in large part to the documentary about their final mission. However, the Belle’s crew was not the first B-17 crew to complete their tour. That distinction goes to the crew of Hell’s Angels (B-17F, serial number 41-24577), which completed its 25th mission on May 13, 1943, five days ahead of the Belle. However, the crew of the Belle was the first to be sent back to the US because the crew of Hell’s Angels signed on for another tour and eventually flew a total of 48 missions before returning to the US in 1944. But Hell’s Angels still wasn’t the first bomber to complete a tour. The crew of the Consolidated B-24 Liberator Hot Stuff completed its 25th mission on February 7, 1943, three-and-a-half months ahead of the Belle, then flew another six missions before returning to the US. Though the Memphis Belle wasn’t the first, she and her crew still serve as a testament to the courage of thousands of young men who flew into harm’s way, many of whom did not return.

* As was the practice at the time, the crews and the planes were often interchangeable. So, while the crew completed its 25th mission on May 17, 1943 while bombing the submarine pens at Lorient, France, Memphis Belle completed her 25th mission two days later with a different crew. Morgan’s crew completed its missions in a total of four different aircraft.

May 18, 1953 – The first flight of the Douglas DC-7. Piston-powered aircraft design reached its zenith during WWII, as transport aircraft and long-range bombers helped win the war for the Allies. But with the arrival of the jet engine at the end of the war, it was only a matter of time before jet power supplanted piston power in the airline industry. Still, in the early post-war period, turbojets were relatively new, and airlines were reluctant to plunge headlong into the new technology. The radial engine airliner still had many more miles to fly, but for the Douglas Aircraft Company, the DC-7 was the end of an era, the final piston-powered airliner produced by the company.

As the range of the modern airliner increased, companies like American Airlines wanted to provide nonstop service from coast-to-coast. But the airlines ran afoul of Civil Air Regulations that dictated that flight crews could fly no more than eight hours in one 24-hour period, and that was not enough time to complete the trip. To stay within the rules, American needed a faster plane. In order for Douglas to commit to building what might quickly end up being an anachronism (the jet-powered DC-8 took its first flight just five years later), American Airlines president C.R. Smith placed an order for 25 aircraft and agreed to cover the $40 million development cost. Still, building the DC-7 was a relative safe bet for Douglas. Sticking with a trusted engine also meant adhering to the design elements that had served Douglas so well in the past. The company based the DC-7’s wing on that of the DC-4, and the fuselage was essentially that of the DC-6 but stretched to accommodate more passengers. The DC-7 was powered by four Wright R-3350 Duplex-Cyclone twin-row 18-cylinder radial engines, the same engine that was used in a host of other aircraft, including the Boeing B-29 Superfortress and Lockheed Super Constellation.

Just six months after the DC-7's first flight, American Airlines began offering nonstop service flying from the west coast of the United States to the east coast, scheduling the flights for just under the required eight hours, even if actual conditions didn’t always permit that. Weather was always a factor and, despite the mature technology of the radial engines, the DC-7 was plagued with engine reliability problems which caused frequent diversions and delayed flights. Nevertheless, the range and speed of the DC-7 was attractive to the airlines. With the arrival of the DC-7B, which added still more power and range, American carriers were able to schedule east-to-west service from the US to Europe. However, the DC-7 remained unattractive to European airlines because the range was still insufficient for west-to-east transatlantic crossings. Douglas responded with the DC-7C (nicknamed Seven Seas), a variant that moved the engines a bit farther outboard on the wings to reduce cabin noise and provided for yet more fuel. The fuselage was stretched once again to make room for more seats.

Despite the transatlantic range and relative reliability of the DC-7C, the days of the piston-powered airliner were rapidly coming to an end. With the advent of the Boeing 707 and Douglas’ own DC-8 jetliner, sales of the DC-7 ground to a halt by the end of the 1950s. But the DC-7 still had lots of life in it. Douglas converted the earlier DC-7s and DC-7Cs into the DC-7F, a freighter variant that came with cargo doors added to the front and rear. Douglas produced the DC-7 from 1953-1958 and built 338 aircraft, roughly half the number of DC-6s they produced. Today, the DC-7 is nearly extinct, and only a handful remain airworthy.

Short Takeoff

May 17, 2020 – The first flight of the Cessna SkyCourier, a twin turboprop utility aircraft designed to carry either passengers or cargo. Cessna parent company Textron launched the SkyCourier in November 2017 as a clean-sheet design upgrade to the earlier single-engine Cessna 208 Caravan. Global delivery company FedEx, which already operates the 208, will be the launch customer, with orders for 50 aircraft and options for a further 50. With room for either 19 passengers, three LD3 cargo containers, or up to 6,00 pounds of cargo, the SkyCourier is powered by two Pratt & Whitney Canada PT6A turboprop engines, has a top cruising speed of 230 mph, and a 460 mile cargo range. The aircraft will enter service with FedEx following certification.

May 17, 1997 – First flight of the McDonnell Douglas X-36, an experimental tailless aircraft built by McDonnell Douglas (prior to its merger with Boeing) to explore flight by an aircraft without a traditional vertical tail assembly. Built at 28-percent scale of a possible manned fighter, the X-36 was remotely controlled by a pilot on the ground and maneuvered via flight controls provided by a forward canard, split ailerons (also called a deceleron), and vectored thrust. The X-36 made 31 successful research flights, and while the aircraft performed beyond expectations and displayed excellent maneuverability and stability, development ceased following the successful test program. Two prototypes were built, and one resides at the National Museum of the United States Air Force, while the other is on display at the Air Force Test Flight Center Museum at Edwards AFB.

May 17, 1987 – An Iraqi fighter fires two missiles into the US Navy frigate USS Stark. During tensions in the Persian Gulf in the 1980s, the US Navy assumed the task of patrolling the Gulf, particularly the strategic Strait of Hormuz, to ensure the safe passage of cargo ships and oil tankers. For reasons that remain in dispute, an Iraqi Dassault Mirage F1 fired two French-made Exocet anti-ship missiles at USS Stark (FFG-31). The first missile penetrated Stark just above the waterline but did not explode, while the second entered the ship and detonated in the crew quarters, killing 37 sailors and injuring 21. Stark’s crew failed to detect either the aircraft or the missiles until it was too late, and no defensive countermeasures were taken to stop the attack. The Iraqis claimed that Stark was in its territorial waters, but the US Navy held that the frigate was in international waters at the time. Facing courts-martial following the incident, Stark’s captain and her Tactical Action Officer both chose early retirement.

May 17, 1981 – The death of Jeannette Piccard. Piccard (née Ridlon) was born on January 5, 1895 in Chicago, Illinois and studied philosophy, psychology and biology at Bryn Mawr College and the University of Chicago before marrying scientist and balloonist Jean Piccard in 1919. Jean had made a name for himself in Belgium for his flights into the stratosphere, and Jeanette became the first licensed balloon pilot in the United States. On October 23, 1934, Jean and Jeannette flew to an altitude of 10.9 miles, an altitude record for women that Jeannette held for 30 years. Later, Jeannette worked as a consultant for NASA’s Johnson Space Center, and finished her life as an Episcopal priest. For her stratospheric flight, Jeannette Picard was posthumously inducted into the International Space Hall of Fame in 1998, and is considered by some to be the first woman in space.

May 17, 1964 – The death of John Moore-Brabazon, 1st Baron Brabazon of Tara. Moore-Brabazon was born in London on February 8, 1884, and learned to fly in 1908. He became the first Englishman to make a recognized flight in England, and received the Royal Aero Club Aviator’s Certificate No. 1 as the first licensed aviator in England. During WWI, Moore-Brabazon played a prominent role in the development of aerial reconnaissance, and became a Member of Parliament after the war. Beginning in late 1942, he chaired the Brabazon Committee, which was formed to investigate the postwar future of the English airline industry. Some of the most important aircraft of the postwar period came from the committee’s work, including the Vickers Viscount, Avro Tudor, and de Havilland Comet, the world’s first jet-powered airliner. The committee also directed the construction of the mammoth Bristol Brabazon airliner (above), although only one was ever built.

March 17, 1948 – The first flight of the turboprop-powered Boulton Paul Balliol. Development of the Balliol was initiated in 1945 with Air Ministry Specification T.7/45 to find a turboprop-powered training aircraft to replace the North American Harvard (T-6 Texan in US service). The prototype aircraft first flew on May 30, 1947 powered by a Bristol Mercury 30 radial engine, but the second prototype was powered by an Armstrong Siddeley Mamba turboprop, making the Mamba-powered Balliol the world’s first turboprop-powered aircraft to take to the air. However, the Air Ministry changed its requirements in 1947, and the Mamba was replaced in production aircraft by the Rolls-Royce Merlin piston engine.

May 17, 1945 – The first flight of the Lockheed P-2 Neptune, a maritime patrol and anti-submarine (ASW) aircraft developed to replace the Lockheed PV-1 Ventura/PV-2 Harpoon. The P-2 entered service in 1947 and was the first aircraft to be fitted with both piston and jet engines, with both types of engine running on the same fuel to save space and limit complexity. Despite the Neptune’s maritime/ASW mission, small numbers of Neptunes were deployed as carrier-based nuclear bombers as a stop-gap measure until dedicated nuclear bombers could be developed. In 1946, a modified Neptune nicknamed Truculent Turtle flew from Perth, Australia to Columbus, Ohio, setting an unrefueled distance record of 11,236 miles, a record for piston-powered flight that was not broken until the Rutan Voyager flew around the world nonstop in 1986. Replaced by the Lockheed P-3 Orion, Neptunes were retired from military service in 1984, though many still fly as civilian water bombers.

May 18, 1969 – The launch of Apollo 10, the fourth manned mission of the Apollo Program and the second mission to orbit the Moon. Apollo 10 served as a dress rehearsal for the Apollo 11 flight that successfully landed on the Moon two months later. After establishing orbit 70 miles above the lunar surface, astronaut John Young, who would later command the first flight of the Space Shuttle, remained in the Command Module while mission commander Thomas Stafford and Lunar Module pilot Eugene Cernan descended to within 8.4 nautical miles of the Moon’s surface. On its return from the Moon, Apollo 10 set a world record for the highest speed attained by a manned vehicle, flying at 24,791 mph before successfully splashing down in the Pacific Ocean on May 26.

May 18, 1953 – Jacqueline “Jackie” Cochran becomes the first woman to break the sound barrier. A pioneering American aviatrix, Cochran was the only woman to compete for the Bendix Trophy, won five Harmon Trophies, and still holds more speed, distance, and altitude records than any other pilot, male or female. During WWII, Cochran helped establish the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP), in which women pilots were trained to ferry military aircraft in the US to free up male pilots for war duty. After the war, Cochran continued setting records in jet aircraft and became the first woman pilot to break the sound barrier while piloting an RCAF Canadair Sabre (the USAF had refused to loan her an aircraft for the attempt), and set the world speed record for a woman pilot by flying 652 mph. She then topped that on June 3 with a speed of 670 mph over a closed course. She was also the first woman to land and take off from an aircraft carrier. Cochran died in 1980 at the age of 74.

May 18, 1951 – The first flight of the Vickers-Armstrong Valiant, a four-engine, high-altitude nuclear bomber and the first of the so-called V bombers (along with the Handley Page Victor and Avro Vulcan). Designed as a strategic nuclear bomber, the Valiant suffered from fatigue cracks that would also plague the other V bombers. Its service life was relatively short, and it was supplanted by its more advanced successors. Before the Valiant’s retirement, the bomber carried out nuclear deterrence missions, conventional bombing, and aerial reconnaissance. Some Valiants were also converted as aerial tankers. A total of 107 were built, and the Valiant was formally retired in 1957.

May 19, 2008 – The first flight of the Sukhoi Superjet 100, a twin-engine, fly-by-wire airliner designed to compete with the Antonov An-148 and other similarly-sized airliners built by Bombardier and Embraer. The Superjet 100 is powered by a pair of PowerJet SaM146 turbofan engines built as a partnership between Snecma of France and NPO Saturn of Russia, and the airliner can carry up to 108 passengers in a dense, single-class configuration. The Superjet made its first revenue flight on April 21, 2011 by Armenian carrier Armavia, though that company went out of business in 2013. As of April 2018, a total of 159 have been built, and work is underway to develop the larger Superjet 130. However, the recent crash of a Superset 100 after a suspected lightning strike, as well as continuing problems with reliability and the acquisition of spare parts, have cast doubts on the ultimate success of the airliner.

May 19, 1967 – The first flight of the Dassault Mirage 5, a supersonic, delta wing attack jet that was derived from the Dassault Mirage III by Dassault Aviation. The Mirage 5 was developed at the request of the Israeli Air Force, who believed that removing avionics from behind the cockpit would allow for more fuel for long-range attack missions. Due to tensions in the Middle East, the French government refused to deliver the fighters to Israel, though they eventually received them through outside sources. The Mirage 5 was also developed into reconnaissance and two-seat variants, and proved popular with export customers, serving in the air forces of 15 nations. A total of 582 were built, and the Israelis eventually used the Mirage 5 as the basis for the domestically-built IAI Kfir fighter.

May 19, 1952 – The first flight of the Grumman XF10F Jaguar, a prototype variable-geometry fighter developed for the US Navy. As fighter design progressed into the 1950s, the trend was moving towards larger, heavier aircraft with greater speed. While swept wings were good for high speed, they weren’t well-suited to low-speed landings, particularly on the straight decks of the carriers of the day. Grumman devised an aircraft that could straighten the wings for landing and takeoff, then sweep the wings back for high-speed flight. The Jaguar was hampered by unreliable engines and poor flight characteristics, and the development of larger carriers with angled flight decks eliminated the immediate need for such an aircraft. However, much of what was learned with the Jaguar was later used on the extremely successful Grumman F-14 Tomcat.

May 19, 1934 – The first flight of the Tupolev ANT-20 Maxim Gorky, an eight-engine transport aircraft and one of the largest aircraft of its era. Its wingspan was nearly that of the modern Boeing 747-400 jumbo jet, and it remained the largest aircraft until the arrival of the Douglas XB-19 long range bomber in 1941. Named after Maxim Gorky, a Russian and Soviet writer and founder of socialist realism, the ANT-20 was an all-metal aircraft based on the construction techniques pioneered by Hugo Junkers in WWI. It was intended to be used as a Soviet propaganda office outfitted with a powerful radio, printing presses, a library and a movie projector. The first ANT-20 crashed, killing 45 people, so a second aircraft was built with more powerful engines. It, too, crashed when the pilot allowed a passenger to take the controls who then unwittingly disengaged the autopilot. All 36 passengers were killed.

Connecting Flights

If you enjoy these Aviation History posts, please let me know in the comments. You can find more posts about aviation history, aviators, and aviation oddities at Wingspan.