Welcome to This Date in Aviation History, getting of you caught up on milestones, important historical events and people in aviation from July 11 through July 14.

July 12, 1980 – The first flight of the McDonnell Douglas KC-10 Extender. In the earliest days of powered flight up through WWII, an aircraft’s range was limited by the amount of fuel that could be carried on board. Aircraft designed for long range flight had to sacrifice fuselage space for fuel, or carry bulky external fuel tanks. The ideal solution was to find a way to refuel an aircraft in the air, and the very first attempt at aerial refueling occurred in the barnstorming era when a stuntman strapped a tank of fuel to his back and climbed from one plane to another. It was effective, though certainly not practical. One of the earliest attempts at a useful system took place in 1923 when two Airco DH.4 biplanes transferred fuel via a long hose strung from one plane to another. But it wasn’t until 1949 that a truly effective aerial refueling system was devised. The US Air Force demonstrated its potential with a nonstop around-the-world flight by a Boeing B-50 Superfortress that was refueled in the air three times by bombers that had been converted to KB-50 tankers.

With the arrival of the jet-powered Boeing KC-135 Stratotanker, aerial refueling for the Air Force became a standard practice, but even that aircraft didn’t have the truly global range required for Air Force operations the world over, a lesson learned during operations in Southeast Asia and the Middle East. The Air Force needed a flying gas station with greater range, and also one that could be refueled in the air itself. During the procurement process, the Air Force realized that the best solution might be found by converting existing commercial airliners for use as refueling aircraft. The new tanker would have to be large, so the Air Force evaluated of the Boeing 747, the McDonnell Douglas DC-10, and the Lockheed L-1011, all wide-body airliners. They also considered a conversion of the Lockheed C-5 Galaxy strategic airlifter. After quickly dismissing the two Lockheed aircraft, Air Force brass ultimately chose the DC-10, and cited its ability to operate from shorter runways as being a principal factor in the selection.

Although the DC-10 required extensive modifications to fill the role of a military tanker, the KC-10 still retains an 88% commonality with its airliner predecessor. Most of the windows were removed, along with the lower cargo doors, and the McDonnell Douglas Advanced Aerial Refueling Boom (AARB) was added to the rear of the aircraft. This flying boom was a significant upgrade to earlier hose systems, as it allowed the refueler, or “boomer,” to control the refueling probe while the receiving aircraft held station below and behind the KC-10. The Extender also employs the probe-and-drogue system used by the US Navy and NATO allies. Three bladder-type fuel cells were installed below the main cabin floor and, combined with the KC-10's own fuel stores, it can carry more than 356,000 pounds of fuel, nearly twice the load of the KC-135. The Extender has an operational range of 4,400 miles, and its mission can be extended with its own ability to refuel from another aircraft. In addition to its enormous fuel load, the KC-10's cargo hold can also carry up to 170,000 pounds of cargo or hundreds of troops.

The first of an eventual 60 KC-10 Extenders entered service with Strategic Air Command in 1981 and quickly became a vital asset to the US Armed Forces worldwide. Extenders have flown in support of missions in Libya, Iraq, Afghanistan, and Syria, and they provide critical support for long range attack missions or ferrying flights, particularly when countries prohibit aircraft from overflying their sovereign territory. The Royal Netherlands Air Force operates a pair of KDC-10 tankers which were converted from existing airliners rather than purpose-built. Two KDC-10s are also operated by civilian refueling companies who provide their services on contract to the US and other nations. Though there was talk of retiring the Air Force’s fleet of KC-10s in 2015 due to budget constraints, the Extender will remain flying, and will complement the upcoming Boeing KC-46 Pegasus tanker when it enters service to replace aging KC-135s.

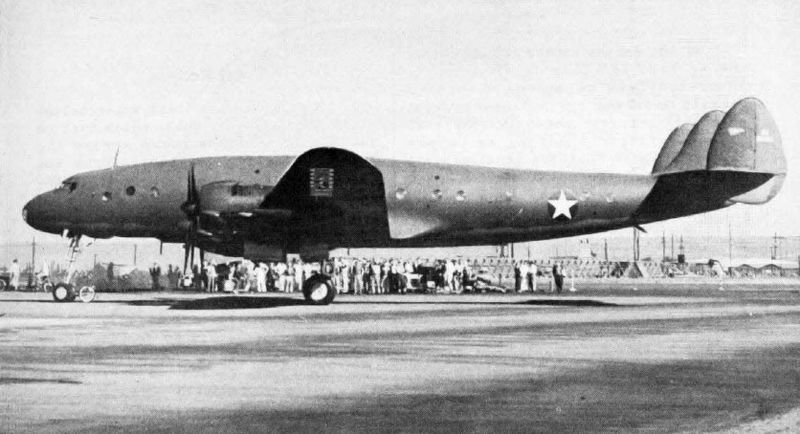

July 14, 1951 – The first flight of the Lockheed L-1049 Super Constellation. While the history of aviation tends to focus on firsts, it is also a story of evolution as much as revolution. Oftentimes, an aircraft that was designed for a single purpose is later developed to fulfill a different role, or a successful design will receive variants to enhance performance or capacity. Such is the story of the L-1049 Super Constellation, which began with the first flight of its L-049 Constellation predecessor in 1943.

Arguably one of the most graceful aircraft ever to take to the skies, the Constellation, nicknamed “Connie,” started life as a much more plain Jane aircraft, the Lockheed L-044 Excalibur, a run of the mill, four-engine transport that never entered production. In 1939, eccentric billionaire Howard Hughes, owner of Transcontinental & Western Airlines (which later became TWA), held a meeting with Jack Frye, the president of T&WA, along with other Lockheed executives. Among those present was Clarence “Kelly” Johnson, who would become one of America’s greatest aviation engineers. Hughes told Lockheed that the Excalibur wouldn’t meet the needs of his airline, and he wanted something entirely new. So Lockheed went back to the drawing board and, in just three weeks time, presented Hughes with the initial plans for the Connie, now designated L-049. The new airliner, powered by a quartet of Wright R-3350 Duplex-Cyclone radial engines, was the most expensive aircraft produced to date, and Hughes himself funded the purchase of 40 aircraft since T&WA didn’t have the funds to pay for them. The first Connies were pressed into military transport service as the Lockheed C-69, but production turned to the civilian market after WWII. The Connie enjoyed a successful airline career, and Lockheed built a total of 865 airliners.

But as flying became more popular, the airlines wanted bigger planes. And Lockheed’s competitors were making strides of their own. In 1950, Douglas came out with the DC-6A, a stretched cargo version of its popular airliner, and were preparing to launch the DC-6B, a passenger variant of the DC-6A, which accommodated 23 more passengers than the Connie. Lockheed had looked into a stretched Constellation, but decided not to build it at the time. However, Douglas’ move forced their hand. Lockheed repurchased the prototype XC-69 Constellation from Hughes Tool Company and lengthened the fuselage by 18 feet, and the newly christened Super Connie now had room for up to 106 passengers.

As Lockheed continued to develop the Super Connie, they added more powerful Wright R-3350 Duplex Cyclone 18-cyliner engines. Compared to the DC-6B, the L-1049 could carry a larger payload, though the Douglas airliner still had a greater range, even when wingtip fuel tanks were added to the Super Connie. Other improvements included strengthened wings and increased cabin soundproofing. The Super Constellation saw service with the US Air Force and US Navy, who flew a total of 320 Super Connies. The EC-121 Warning Star served as an electronic surveillance platform for the US Air Force, while the Navy flew the bulk of the military constellations for transport and early warning. Most of the Super Connies were retired with the advent of jet transports such as the Boeing 707 and Douglas DC-8, and the last commercial flight of the L-1049 was made by Dominican Airlines in 1993. The last military variant was retired in 1982. Two Super Connies remain airworthy, with a small number of others awaiting or undergoing restoration.

Short Takeoff

July 11, 1979 – Skylab re-enters Earth’s atmosphere. Skylab was an orbiting space station that was placed into Earth orbit on May 14, 1973. The first manned mission to the station launched on May 25, 1973 and was planned primarily to repair damage suffered during the station’s launch. Two subsequent missions were flown to place crews on the station to carry out scientific experiments in microgravity. Skylab orbited Earth 2,476 times, and the third mission, Skylab 4, set a new record for time in space when the astronauts remained on board for 84 days. NASA planned to use the Space Shuttle, then under development, to boost Skylab to a higher orbit and keep it functioning, but delays in the Shuttle program made that impossible. When Skylab re-entered the atmosphere, parts of the station landed in the Pacific Ocean and on western Australia, but no injuries were reported from falling debris.

July 12, 1979 – The death of Georgy Mikhailovich Beriev. Beriev was born on February 13, 1903 in present-day Tbilisi, Georgia. A student of both shipbuilding and aircraft engineering at the Leningrad Polytechnic Institute, Beriev is best known as the designer of numerous amphibious aircraft. He founded the Beriev Aircraft Company in 1934 and received the Stalin Prize for development of the Beriev Be-6, which was designed for maritime patrol and attack. Though most designers stopped making amphibious aircraft with the transition to jet engines, Beriev developed a number of innovative jet-powered amphibians, including the Be-40 Albatros and Be-200 Altair, and pilots flying his seaplanes have set 228 aviation world records for the type.

July 12, 1966 – The first flight of the Northrop M2-F2, the second of three NASA aircraft designed to investigate the feasibility of wingless aircraft. Without wings, the shape of the aircraft itself, called a lifting body, provides the lift. It was thought that by eliminating conventional wings it would also eliminate the drag that comes with them. During the 1960s and 1970s, lifting bodies were a primary area of research into their use as small manned spacecraft. Eventually, the Air Force lost interest in the project, and NASA turned its efforts to the Space Shuttle. The M2-F2 was a development of the earlier M2-F1, and sixteen unpowered glide tests were carried out before the aircraft was modified into the M2-F3 which was capable of supersonic flight.

July 12, 1957 – President Dwight Eisenhower becomes the first US president to fly in a helicopter. Today, flying in a helicopter is a routine practice for the US president. But in 1957, helicopters were still relatively new and were not deemed safe enough for presidential travel. With Cold War concerns over the ability to evacuate the president from the White House by road, the Secret Service decided that a helicopter was the best solution, and President Eisenhower made the first presidential flight in a US Air Force Bell 47J Ranger from the White House to the presidential retreat at Camp David. Today, transporting the president by helicopter is an everyday occurrence, and it is now the responsibility of US Marine Corps helicopter squadron HMX-1.

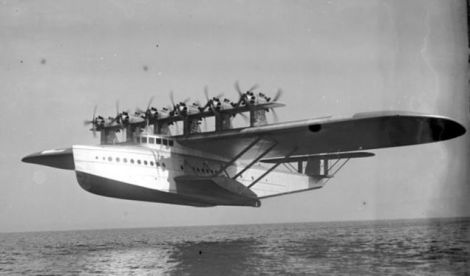

July 12, 1929 – The first flight of the Dornier Do X, a huge, 12-engine flying boat built by Claude Dornier and the largest, heaviest, and most powerful flying boat in the world at the time. Built in Switzerland in order to circumvent the restrictions of the Treaty of Versailles, the Do X was powered by twelve Curtiss V-1570 Conqueror V-12 engines in a combined push-pull configuration and had a top speed of 131 mph. The Do X could accommodate up to 100 passengers, and set a world record for its day when it carried 169 passengers and crew, a record that stood for 20 years. However, Dornier had trouble finding customers for his giant flying boat, and only three were ever built.

July 12, 1921 – The death of Harry George Hawker. Hawker was an Australian aviation pioneer, chief test pilot for Sopwith during WWI, and founder of Hawker Aircraft. Born on January 22, 1889, Hawker began his career as an auto mechanic in England before starting work with Sopwith as a mechanic. He convinced them to teach him to fly, and Hawker soloed after just three lessons. Following the liquidation of Sopwith Aircraft in 1920, Hawker teamed with Thomas Sopwith to start a new company, H.G. Hawker Engineering. Though Hawker died soon after in the crash of his Nieuport Nighthawk, his company continued. Through a series of acquisitions and mergers it became Hawker Siddeley, though it continued to make aircraft with the Hawker name. These included some of the most important and iconic aircraft of WWII, particularly the Hurricane and Typhoon.

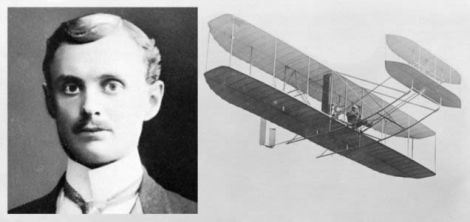

July 12, 1910 – The death of Charles Stewart Rolls. Charles Rolls is best known to automotive history as one half of the famed Rolls-Royce Limited manufacturing company, which he formed with Henry Royce in 1906. But Rolls, born on August 27, 1877, was also a pioneering aviator, first in ballooning, then in airplanes. Rolls purchased a Wright Flyer Model A in 1909 and, while not the first to cross the English Channel, he was the first to make the crossing and then return immediately, thus also becoming the first to cross the Channel flying eastward. Unfortunately, Rolls also achieved another, more tragic first, when he became the first Briton to die in an airplane accident following the crash of his Wright Flyer in 1910.

July 13, 1982 – The death of LCDR Barbara Allen Rainey. Born on August 20, 1948, Rainey was the first female aviator in the history of the US military when she received her Wings of Gold as a Naval Aviator in 1974. She was also the first woman qualified as a military jet pilot. After retiring from active duty, Rainey joined the Naval Reserves, but returned to active duty as an instructor flying the Beechcraft T-34 Mentor. She and a student were killed in a training crash while practicing touch-and-go landings. Due to the extensive damage to the aircraft, the cause of the crash could not be determined. Rainey was 33 years old.

July 14, 1971 – The first flight of the VFW-Fokker 614, a twin-engined medium-range jetliner designed and built in West Germany as a replacement for the Douglas DC-3 and notable for the placement of its two engines in pods above the wings rather than below. The location of the two Rolls-Royce/SNECMA M45H turbofan engines avoided the added structural weight of attaching them to the rear fuselage, and also helped eliminate the possibility of ingestion of debris common in underwing mountings. Due to cost and development delays, only a handful were produced before the project was canceled in 1977. Unfinished aircraft were broken up, and the remainder were bought back by the manufacturer.

July 14, 1965 – Mariner 4 flies past Mars. Mariner 4 was part of NASA’s Mariner program that explored planets in the Solar System by flying past to make scientific observations and return photographs. Mariner 4 was launched from Cape Canaveral on November 28, 1964 and, after its arrival at Mars, it sent back the first images ever returned from deep space. The views of a cratered, seemingly lifeless world changed many scientific opinions previously held about the Red Planet. Mariner 4 collected data for two days as it flew past Mars, and remains in its heliocentric orbit following termination of communications on December 21, 1967.

July 14, 1955 – The first flight of the Martin P6M SeaMaster. With the US Air Force becoming the dominant nuclear force after WWII, the US Navy sought to remain relevant in the nuclear strike business by developing a jet-powered strategic bomber that could operate from the world’s oceans and not be tied to carriers or land bases. The SeaMaster arose from a Navy requirement for a sea-based bomber that could carry a 30,000-pound payload over a range of 1,500 miles, and its four Allison J71 turbojets were fitted in the high wing high to prevent ingestion of water. Though the first two prototypes were lost to fatal crashes, development of the SeaMaster continued, and a total of 12 were eventually built. On the verge of entering operational service, the SeaMaster was canceled following the development of the submarine-launched Polaris missile, and the Navy was unsuccessful in marketing the plane as a jet-powered minelayer. Following its cancelation, all copies of the SeaMaster were scrapped.

July 14, 1948 – The first flight of the Supermarine Seagull, an amphibious air-sea rescue and maritime reconnaissance aircraft and the last propeller plane built by the famed Supermarine company. As the name Supermarine suggests, the company got its start making floatplanes, and found fame by winning the Schneider Trophy seaplane races in 1927, 1929 and 1931. Work on the Rolls-Royce Griffon-powered Seagull began late in WWII to develop a catapult-launched amphibian to replace the Supermarine Walrus and Sea Otter. However, by 1950, when the Seagull was to have entered service, its role had been taken over by helicopters and only two prototypes were built. Supermarine was incorporated into the British Aircraft Corporation in 1960.

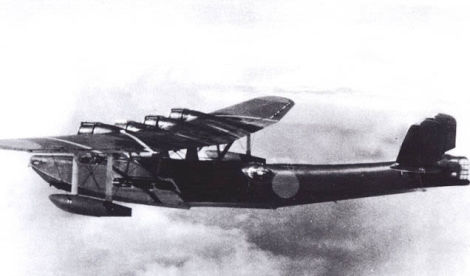

July 14, 1936 – The first flight of the Kawanishi H6K, a maritime patrol flying boat built for the Japanese Navy. Influenced by the work of the Short Brothers in Ireland and the earlier Kawanishi H3K, itself a license-built and enlarged version of the Short Rangoon, the H6K entered service in 1938 and saw service in the Second Sino-Japanese War and WWII. Though vulnerable to modern fighters flown by the Allies during WWII, the H6K remained in service until the Japanese surrender in 1945, but was replaced in front line service by the more modern Kawanishi H8K. A total of 215 were produced.

July 14, 1933 – Wiley Post departs on the first solo circumnavigation of the globe. Post had previously made a trip around the world in 1931 with navigator Harold Gatty, finishing the trip in eight days and beating the previous record of 21 days held by the airship Graf Zeppelin (LZ 127). For his second flight, Post set off alone from Floyd Bennett Field, again in the Lockheed Vega Winnie Mae and, using an autopilot and compass in place of a navigator, completed the journey in just over seven days, breaking his own record. Post was greeted in New York by a throng of 50,000 people, and the Winnie Mae now resides in the Smithsonian’s Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in northern Virginia.

Connecting Flights

If you enjoy these Aviation History posts, please let me know in the comments. And if you missed any of the past articles, you can find them all at Planelopnik History. You can also find more stories about aviation, aviators and airplane oddities at Wingspan.