Welcome to This Date in Aviation History, getting of you caught up on milestones, important historical events and people in aviation from August 1 through August 4.

August 1, 1955 – The first flight of the Lockheed U-2. At the close of World War II, the Communist Soviet Union was firmly in control of much of Eastern Europe, while the Democratic western allies held Western Europe. It was the beginning of the Cold War, an ideological struggle between East and West. And while it never broke out into WWIII, the struggle brought about an arms race, space race, and numerous proxy wars as the two sides strived to become the dominant influence in the world. In the early stages of the Cold War, the United States was desperate for accurate and timely intelligence on Russian military activities. Today, that sort of information is gained by powerful satellites, but even when satellites began providing pictures from the safety of space in the 1960s they were unreliable. Far ranging reconnaissance aircraft like the Boeing RB-50, a variant of the WWII-era B-29 Superfortress, and the jet-powered Boeing RB-47 Stratojet, probed the edges of the Soviet Union, but it was hazardous duty and many planes and pilots were lost to Russian fighters and antiaircraft fire. What the US desperately needed was an aircraft that could fly high enough to be out of range of Soviet fighters, and perhaps even out of the range of Russian radars.

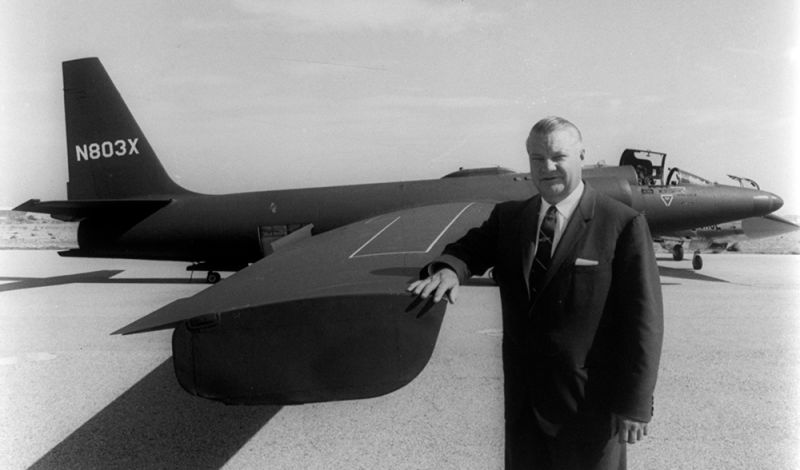

The US already had in their arsenal the Martin B-57 Canberra, the American-built version of the remarkable English Electric Canberra. The B-57 had a ceiling of 48,000 feet, just beyond the reach of Russian MiG-15 fighters. For added safety, Martin lengthened the wings of the B-57 in the hopes of reaching 70,000 feet, but came up 2,000 feet short. So the Air Force sent out requests to other aircraft manufacturers who might be able to devote all of their attention to this important project. However, Lockheed was not one of them. Nevertheless, the company heard of the project and submitted their own proposal, dubbed the CL-282, designed by the brilliant Clarence “Kelly” Johnson. Initially based on Lockheed’s XF-104, the single engine CL-282 had long, slender wings and was powered by a single General Electric J73 engine housed in a short fuselage. To save weight, the CL-282 had no landing gear, and would take off from a rolling cart and land on its belly. Even though the CL-282 promised the performance the Air Force requested, and perhaps even more, they passed on the Lockheed design in favor of a Bell aircraft that never actually flew. The CL-282 passed to the Central Intelligence Agency.

The CIA’s codename for the project to develop the CL-282 was Dragon Lady, which ended up giving the finished U-2 its unofficial nickname. But the CL-282 needed some improvements to make it operational. Lockheed added landing gear in the form of two wheels directly behind the cockpit, and another pair of wheels behind the engine. The rear wheels are coupled to the rudder and provide steering on the ground. Outrigger wheels on the wingtips, called pogos, keep the wingtips off the ground during taxi and takeoff. The pogos fell out on takeoff, and were replaced after landing. The wingtips were protected by titanium skid plates. The engine was also upgraded to the more powerful and proven General Electric J57 turbojet. The J57 added even more altitude to the U-2, which now had a service ceiling of nearly 75,000 feet, high enough to see the curvature of the Earth. So high, in fact, that pilots breathe 100% oxygen beginning an hour before their mission, and wear space suits in case the cockpit depressurizes at altitude.

Test flights began in 1956, and the Dragon Lady entered service the following year. CIA pilots, all civilians (military pilots were not allowed to make reconnaissance flights over the Soviet Union), were called “drivers” rather “pilots.” With its long slender wing and unpowered controls, the U-2 was very difficult to fly at lower altitudes, and required constant attention at high altitude. In 1956, three U-2s crashed with the loss of the pilot. Despite these difficulties, the first U-2s were deployed to Germany in 1956 and began with overflights of East Germany and Poland in June, followed by the first overflights of the Soviet Union the following month. Though the Dragon Lady could be tracked more accurately by Soviet radars than the US thought possible, the high-flying spy plane remained out of reach of the fighters sent up to knock it down. U-2s also made flights over other global hotspots such as the Suez, and later over Cuba and Vietnam. Despite the relative safety of extreme altitude, the Russians did mange to claim one U-2 when CIA pilot Francis Gary Powers was shot down by a surface to air missile on May 1, 1960. Another was shot down over Cuba in 1962.

Though very much a product of the Cold War, the U-2 remains in service today, and has provided intelligence for conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan more than 60 years after its maiden flight. The airframe has been updated with more powerful General Electric F118 turbofans along with upgraded sensors and cameras. The ability to change sensors quickly for different mission parameters makes the U-2 a valuable asset to this day. NASA also flies updated ER-2 variants for high altitude research. With the capability to provide critical reconnaissance with more flexibility than orbiting satellites, and paired with the judgement of a human pilot, it is likely that the U-2 will continue flying for years to come.

August 1, 1936 – The death of Louis Blériot. The Wright Brothers made history in 1903 with their flight at Kill Devil Hills, North Carolina, and while they are widely recognized as being the first to fly a fully controllable aircraft (some contend that they weren’t really the first), aviation pioneers in Europe were working hard to catch up to them. Three years after the Wright Brothers’ historic flight, Brazilian inventor Alberto Santos-Dumont, working in France, made a public flight in his Santos-Dumont 14-bis, which resembled a giant box kite, while Frenchman Gabriel Voisin made the first flight of his Voisin biplane in 1907. Despite the news surrounding the successful flights of the Wright Brothers, many in Europe remained skeptical of their achievements. To prove the doubters wrong, Wilbur Wright traveled to Europe in 1908 and made a series of demonstration flights near Le Mans, demonstrating just how far he and his brother Orville had come with their Wright Flyer. Wilbur made numerous demonstrations in which he flew circles and figure-eights that stunned the French audience. One member of the audience that day was Louis Blériot.

Though he is best known today for his pioneering work in aviation, Blériot originally made his money as an inventor and engineer. He was born on July 1, 1872 at Cambrai, France, and following his education at the prestigious École Centrale in Paris and compulsory military service with an artillery regiment, he went to work for an electrical engineering firm where he developed the first practical headlamp for automobiles. The money he earned from this invention funded his foray into aviation. Blériot began with attempts at building ornithopters, but these flapping-wing designs proved unsuccessful for what today seem obvious reasons. In 1905 he met Voisin, and the two agreed to work together. They formed the Ateliers d’ Aviation Edouard Surcouf, Blériot et Voisin, but the partnership was unsuccessful, and Blériot realized that he was still far from his goal. After witnessing a successful flight by Santos-Dumont, Blériot dissolved his partnership with Voisin and struck out on his own. He continued experimenting with different configurations and, at a time when most aircraft pioneers were working with multiple wings, Blériot instead focused on the development of the world’s first powered monoplane, the Blériot V, which took its maiden flight on March 21, 1907. The aircraft only made short flights, and was damaged beyond repair after its third flight, but Blériot was on his way.

Numerous modifications and experiments followed, and his Blériot VII, with a large forward wing and smaller tail wing, established the basic layout of almost all aircraft to follow. The controls of the Blériot VII featured tail surfaces that could be moved together or separately and were the precursor to the elevators, ailerons, and elevons used in modern aviation. Though the success of the Blériot VII established Blériot as a pioneering innovator, his greatest public notoriety came when he completed the first successful crossing of the English Channel. On July 25, 1909, the Frenchman took off from Calais at 4:41 am in his Type XI monoplane which was powered by a 25-horsepower, 3-cylinder Anzani engine. After a 36-minute flight, Blériot made a hard landing in Dover and claimed the £1000 prize which was being offered by the British newspaper the Daily Mail. The feat brought him fame and helped the success of his aircraft manufacturing business, and led to 100 orders for his Type XI and more than 900 orders for aircraft during WWI.

Blériot continued his manufacturing work after the war, and was present at Le Bourget Airport in 1927 to welcome Charles Lindbergh to Paris after his solo crossing of the Atlantic Ocean. Blériot died in 1936 at the age of 64 and, in his honor, the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale established the Louis Blériot Medal to recognize records set in speed, altitude and distance.

August 2, 1966 – The first flight of the Sukhoi Su-17. Before the adoption of the jet engine, most aircraft, dating back to the Wright Flyer, were built with straight wings. Generally, straight wings provide good low-speed stability and handling, but the advent of the turbojet engine during WWII led designers to experiment with swept wings that would incur less drag at higher speeds. However, swept wings also had the drawback of requiring higher landing speeds. But what if you could design an airplane that could benefit from both straight and swept wings? As early as 1944, the idea of having an airplane with a variable-sweep wing (also called variable-geometry) was being investigated in Germany with the Messerschmitt Me P.1101. But this aircraft, which never entered production, could only change the sweep of the wings to a fixed position before takeoff. In England, Barnes Wallis began working on a swing-wing concept in 1949, but it wasn’t until the experimental Bell X-5, which first flew in 1951 and had three different wing positions, that an aircraft could change its wing sweep in flight.

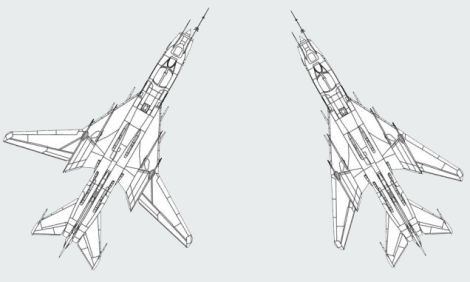

However, one of the problems faced by variable geometry aircraft is an unfavorable shift in the airplane’s center of gravity when moving between the straight and swept positions. To counter this problem, Russian designers at the Central Aerohydrodynamic Institute (TsAGI) modified an existing Sukhoi Su-7B to use a fixed central wing with a variable outer wing in the hopes of improving the Su-7's low-speed flight characteristics and lowering its landing speed. This new aircraft, dubbed the Su-7IG, was further developed into the Su-17 and became Russia’s first variable geometry aircraft. Along with the modified wing, Sukhoi gave the Su-17 a new canopy, and a dorsal spine for additional fuel and avionics. The new variable sweep fighter was the first in a series that also included the Su-20 and the Su-22 and, despite the different Sukhoi classifications, all of these variants received the NATO reporting name Fitter.

The Fitter was powered by a single Lyulka AL-21 afterburning axial flow turbojet that gave it a top speed of 870 mph and was armed with two 30mm cannons. Up to 8,800 pounds of external stores could be carried under the fixed wing section or on the fuselage. The Su-17 entered service with the Soviet Air Force in 1970, where it served during the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan from 1979-1989. While high elevation and high temperature operations proved challenging for the Su-17, the ruggedly constructed engine was tolerant to sand ingestion and the Fitter maintained a high level of readiness, though it proved susceptible to anti-aircraft fire and shoulder-fired antiaircraft missiles. The Fitter was widely exported to Soviet allies, and eventually served for over 20 years with the Soviet Air Force and 15 export countries, including Libya, where two Su-17s were shot down by US Navy Grumman F-14 Tomcat fighters over the Gulf of Sidra in 1981. Despite advances in Soviet fighter design, the Su-17 and its derivatives remained in service with Russia until 1998, and more than 500 of the 2,867 aircraft produced remain in service today.

August 4, 1954 – The first flight of the English Electric Lightning P.1A. The world entered the nuclear age on August 6, 1945 when the US dropped the first of two atomic bombs on Japan in the hopes of ending the war and avoiding a costly invasion. Though we live today with the Damoclean sword of intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBM), 14 years passed after WWII before the Soviets fielded the world’s first operational ICBM in 1959. During those intervening years, the only method of delivering a nuclear weapon to a target was with high-flying high-speed bombers designed to outrun defensive fighters. Therefore, it was vital to intercept the nuclear-armed bombers as early as possible, and this called for a special breed of fighter aircraft, one that could take off at a moment’s notice and fly as fast as possible to reach the bombers before the bombers could reach their target.

The idea of an interceptor was not new, and the concept dates all the way back to WWI. But in the jet age, supersonic speed became the all important factor in their development. When the British Aircraft Corporation Lightning entered service in 1960, it was the Royal Air Force’s only interceptor capable of Mach 2 speed. But this modern bomber hunter traces its roots all the way back to 1947, when English Electric, the maker of the Canberra bomber, was awarded a contract to develop a supersonic research aircraft. English Electric designers knew they would have to employ a swept wing to achieve supersonic speeds, but they first had to determine the optimal amount of sweep. To do this, the company contracted with the Irish firm Short Brothers to create the Short SB.5, a scaled down research aircraft whose wing and tailplane could be adjusted to different angles for testing. Based on data gathered from the SB.5, English Electric chose an untapered wing with a severe 60-degrees of sweep, giving the Lightning its unique shape.

Another feature unique to the Lightning was its engine layout. Rather than place two turbojet engines side-by-side, English Electric stacked the engines one on top of the other. This arrangement gave the Lightning the power to reach Mach 2 while also reducing drag and minimizing the frontal area of the fighter. The prototype Lightnings were powered by a pair of Armstrong Siddeley Sapphire non-afterburning (or “non-reheating” to the British) axial flow turbojets. Though the Sapphires were not as powerful as the Rolls-Royce Avon turbojets which would be fitted on production Lightnings, the interceptor still passed the sound barrier on its maiden flight. Following the successful testing of the prototypes, the P.1B, with its new Avon turbojet engines, took its first flight 1957, and the addition of a crude afterburner meant the Lightning could now reach Mach 2. With so much power available to Lightning pilots, the interceptor could achieve an altitude of 36,000 feet in less than three minutes, and tests showed that the Lightning was capable of intercepting a high-flying Lockheed U-2 spyplane. But all that speed came at a cost. The Lightning burned fuel voraciously, and many of its missions were determined simply by the amount of fuel it could carry.

The Lightning entered service with the RAF in 1960 as the Lightning F1, and its primary mission was intercepting Soviet bombers and providing protection to airfields so British nuclear bombers, known as the V Force, could take off. Subsequent variants added to the Lightning’s capability with more weapons and improved radar. While the RAF was the primary operator of the Lightning, it was also exported to Kuwait and Saudi Arabia, and a total of 337 aircraft were produced. In its nearly 30 years of service, the Lightning was never used in combat, and only claimed one aircraft shot down: an unmanned RAF Hawker Siddeley Harrier that was flying towards East Germany after its pilot ejected. Nevertheless, Lightnings kept vigil on the border so of the British Isles and intercepted Soviet reconnaissance aircraft. The RAF retired their Lightnings in 1988, but a small number of aircraft still flying in the hands of private pilots.

Short Takeoff

August 1, 2002 – The first flight of the Scaled Composites White Knight, an aircraft designed to launch the SpaceShipOne experimental spacecraft as part of a program to take paying passengers into space. Designed by Burt Rutan, White Knight is powered by two General Electric J85 turbojet engines and carried the SpaceShipOne to an altitude of 45,000 feet before releasing the spacecraft to fly on its rocket motor. While Knight made a total of 17 flights with SpaceShipOne before it was replaced by the larger and more powerful White Knight Two. Following the completion of the SpaceShipOne test program, White Knight carried out drop tests of the Boeing X-37 Orbital Test Vehicle, and was retired to the Flying Heritage Collection in Everett, Washington in July 2014.

August 1, 1973 – The first flight of the Martin Marietta X-24B, an experimental wingless aircraft developed jointly between the US Air Force and NASA to explore the design of lifting body aircraft. The X-24 was dropped from a Boeing B-52 Stratofortress, then powered by a rocket engine in flight before gliding to a landing. The lifting body research was carried out from 1963 to 1975 to investigate wingless vehicles that could land on Earth after flying in space, and data gained during these experiments was put to use in the design of the Space Shuttle. The X-24B made a total of 36 test flights before it was retired to the National Museum of the United States Air Force in Dayton, Ohio.

August 1, 1949 – The first flight of the Northrop C-125 Raider. Following WWII, Northrop’s first offering for a civilian airliner was the three-engine N-23 Pioneer. However, with so many surplus aircraft available, airlines showed little interest. So Northrop instead pitched it to the US Air Force as the C-125 Raider to fulfill the roll of a short takeoff and landing (STOL) cargo carrier. The Air Force placed an order for 23 aircraft, and Raiders began to enter service in 1950. However, the Raider proved to be underpowered, and they were quickly relegated to ground training duty and declared surplus just five years after their introduction. Most of the remaining aircraft ended up flying cargo in South and Central America. Two non-airworthy Raiders remain, one on display at the Pima Air and Space Museum in Arizona and the other at the National Museum of the United States Air Force in Ohio.

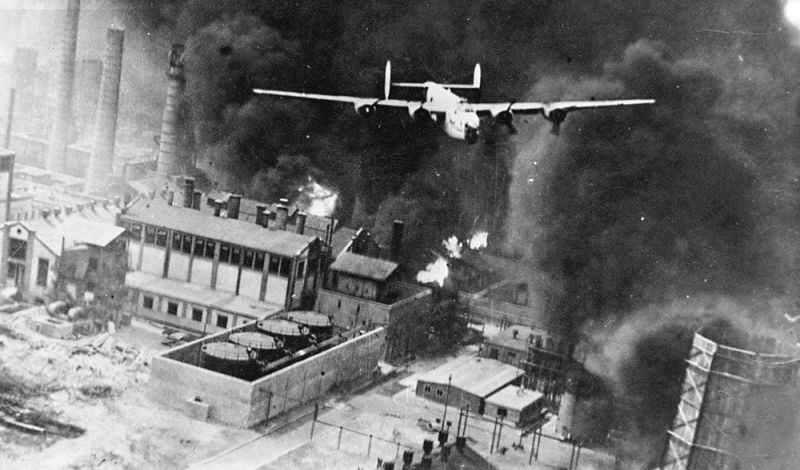

August 1, 1943 – American bombers carry out Operation Tidal Wave, the low level bombing of Axis oil production facilities near the Romanian city of Ploiești. Hoping that the destruction of oil production would force the Nazi war machine to grind to a halt, 177 unescorted Consolidated B-24 Liberators of the 3rd Air Force took off from bases in Libya and flew across the Mediterranean and Adriatic Seas to Romania. Though the Liberator was designed as a high altitude bomber, the decision was made to carry out the mission at extreme low level, hoping to evade German radar. However, the defenders were alerted long before the bombers reached the target, and a series of navigation errors, compounded by strict radio silence, completely derailed the complex coordinated attack. Three of the groups attacked from the wrong direction and bombed targets of opportunity rather than their assigned targets, while the other two groups, who followed the original plan, found their targets already hit. Therefore, some targets were bombed twice while others remained unscathed. The bombers were savagely mauled by flak and fighters and, of the original 177 aircraft that left Libya, only 88 returned to base, and 55 of those had battle damage. Other damaged bombers ditched in the Mediterranean Sea or landed in neutral Turkey. In all, 53 bombers were lost and 660 airmen were killed, making it the costliest single raid of the war for the Americans. For pressing the attack despite the terrible odds, 56 Distinguished Service Crosses and five Medals of Honor were awarded to the crews. Ultimately, the raid proved ineffective at curtailing the supply of oil, and Ploiești was not attacked again until April 1944 with the arrival of long range escort fighters.

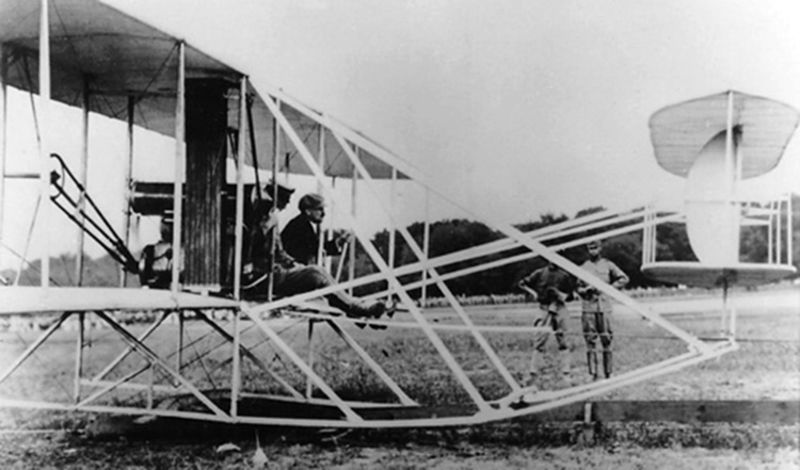

August 1, 1907 – The Aeronautical Division of the United States Army Signal Corps is created “to study the flying machine and the possibility of adapting it to military purposes.” Though initially cool to the role of the airplane in the military, the US Army began to show interest in the Wright Brothers’ invention four years after the famous first flight. The Aeronautical Division was the world’s first heavier-than-air military aviation organization, and the Army purchased their first aircraft, a Wright Model A, also known as the Military Flyer, on August 2, 1909. The Aeronautical Division saw its first action in 1913 when the 1st Aero Squadron was sent into Mexico to take part in the hunt for Pancho Villa. The Aeronautical Division eventually gave way to the US Army Air Corps and US Army Air Forces in WWII, and then became its own equal branch of the military with the creation of the US Air Force in 1947.

August 2, 1917 – Royal Naval Air Service pilot Edwin Harris Dunning becomes the first pilot to land on a moving ship. In 1910, American Eugene Ely had made the first landing on a ship moored in Hampton Roads, but to make carrier operations useful an aircraft would have to land while a ship was underway. In the era before arresting wires and tail hooks, Dunning had to rely on crew members assembled on deck to grab his Sopwith Pup and bring it to a halt. He made two successful landings on HMS Furious as it steamed in Scapa Flow in northern Scotland, but on his third attempt a gust of wind caused his aircraft to veer off the deck and into the water. Dunning was rendered unconscious and drowned. He was just 25 years old.

August 2, 1985 – The crash of Delta Air Lines Flight 191, regularly scheduled Lockheed L-1011 TriStar (N726DA) service from Fort Lauderdale to Dallas-Fort Worth that crashed while trying to land during a thunderstorm. Lacking the sophisticated Doppler radar found on today’s airliners that warns pilots of wind speeds in a storm, the airliner was struck by microburst-induced wind shear at low altitude that caused the L-1011 to crash a mile short of the runway. (A recreation of the landing profile, with cockpit audio, can be seen here.) Of the 163 passengers and crew, 136 were killed in the crash, and two more passengers died a month later. One driver on the road outside the runway fence was struck and killed as the airliner careened across the road outside the runway fence. Most of the survivors were seated in the rear of the plane which broke away. The National Transportation Board investigation faulted the pilots for choosing to land through the storm, as well as a lack of training for dealing with wind shear. As a result of this crash, the Federal Aviation Administration now mandates wind shear detection systems on all commercial aircraft. A memorial plaque placed at Founder’s Plaza next to the DFW Airport commemorates the tragedy.

August 2, 1960 – The first flight of the Bennett Airtruck, an agricultural aircraft constructed from surplus Royal New Zealand Air Force North American Harvard (T-6 Texan) training aircraft. The Airtruck is essentially an agricultural chemical hopper with wings, engine, and twin-boom tail, with the cockpit placed on top. As many as five passengers could also be carried instead of chemicals. Two were built, though the first crashed in 1963, and the second crashed two years later. Despite the loss of the prototypes, the Airtruck proved to be a very efficient agricultural aerial top dresser. The design was transferred to the Transavia Corporation which produced the Transavia PL-12 Airtruk, a similar aircraft that was manufactured from scratch and did not use scavenged Harvard parts.

August 2, 1911 – Harriet Quimby becomes the first American woman to be certified as a pilot. At a time when flying was dominated by male pilots, Quimby, a Hollywood screenwriter, became the first woman to earn a pilot license in the United States, and her flying exploits served as an inspiration to many women of her day. Quimby was hired as a spokesperson for the Vin Fiz Company and became the first woman to fly across the English Channel in 1912, a feat that was unfortunately overshadowed by news of the sinking of the Titanic just one day later. Quimby was killed on July 1, 1912 when her Blériot XI monoplane was struck by a gust of wind and suddenly pitched forward, ejecting both her and her passenger at an altitude of 1,500 feet over Dorchester Bay. The pilotless plane came down relatively intact.

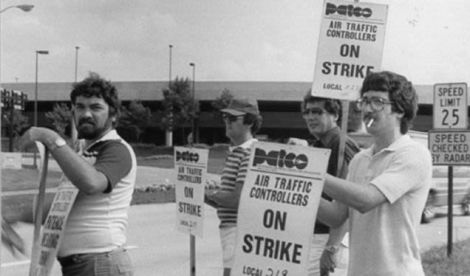

August 3, 1981 – The Professional Air Traffic Controllers go on strike. Air traffic controllers in the US had been unionized since 1970 and had a history of poor relations with the Federal Aviation Administration. Demanding better pay, better working conditions, and a 32-hour work week, controllers went on strike in 1981 in contravention of established US laws prohibiting strikes by federal employees. Under the provisions of Taft-Hartley Act, President Ronald Reagan ordered the striking controllers back to work. When they refused, 11,345 controllers were fired and banned for life from federal service. In 1993, President Bill Clinton reversed the ban, but only 800 controllers regained their jobs, and it took 10 years to fully staff the nation’s air traffic system.

August 3, 1945 – The first flight of the Kyushu J7W Shinden, an interceptor developed for the Japanese Navy and notable for its use of a pusher propellor and forward canard. Similar in layout to the Curtiss-Wright XP-55 Ascender, the Shinden (Magnificent Lightning) was developed to provide defense against Boeing B-29 Superfortress raids on the Japanese homeland, and designers planned that the propeller engine could be supplanted by a jet engine in the future. The navy ordered the Shinden into production off the drawing board, but the war ended before development progressed beyond the construction of two prototypes.

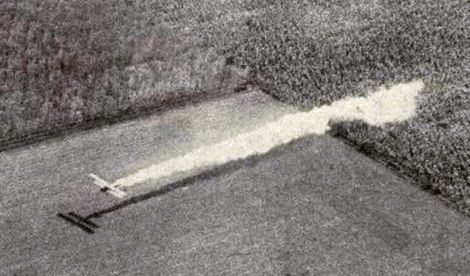

August 3, 1921 – The first use of an aircraft to apply pesticides to crops. Aerial application, popularly known as crop dusting, was first done from the air in 1906 in New Zealand when seeds were spread from a balloon. But the modern method of using airplanes began in 1921 when US Army pilot Lt. John Macready flew a modified Curtiss JN-4 Jenny over a field in Ohio, spreading a load of lead arsenate to kill catalpa sphinx caterpillars as part of a joint operation between the US Agriculture Department and the US Army Signal Corps. Today, crop dusting is performed the world over by both converted and purpose-built airplanes, helicopters, and even unmanned aerial vehicles.

August 4, 1971 – The first flight of the AgustaWestland AW109, a twin-engine lightweight helicopter and the first all-Italian helicopter to enter mass production. Agusta (now AgustaWestland, a subsidiary of Leonardo-Finmeccanica) originally designed the A109 in the late 1960s with a single engine, but it soon became evident that a second engine was necessary to provide the required lifting power. Today, the AW109 is powered by a pair of Pratt & Whitney Canada PW200 turbine engines and can accommodate up to seven passengers at a top speed of just under 200 mph. The AW109 entered service in 1976 and is flown by military and government agencies all over the world, and commonly serves as an air ambulance or for corporate transportation.

Connecting Flights

If you enjoy these Aviation History posts, please let me know in the comments. You can find more posts about aviation history, aviators, and aviation oddities at Wingspan.