Welcome to This Date in Aviation History, getting of you caught up on milestones, important historical events and people in aviation from August 5 through August 7.

August 5, 1943 – The Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP) is formed. Prior to the enactment of the Women’s Armed Services Integration Act in 1948, which enabled women to serve as permanent, regular members of the US armed forces, most American women served in non-military support organizations such as the US Navy’s Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service (WAVES) and the US Army’s Women’s Army Corps (WAC). The only way for women to serve officially in the active duty military was as a nurse or in other support roles. During WWII, about 400,000 American women answered their country’s call, and more than 500 died, 16 from enemy fire. But with so many American men fighting overseas or serving in the military stateside, jobs that were traditionally filled only by men were being very capably filled by women for the first time. Rosie the Riveter became a symbol of the new American workforce helping to supply Arsenal of Democracy with planes, tanks, and ammunition, and for the first time, women began serving as pilots.

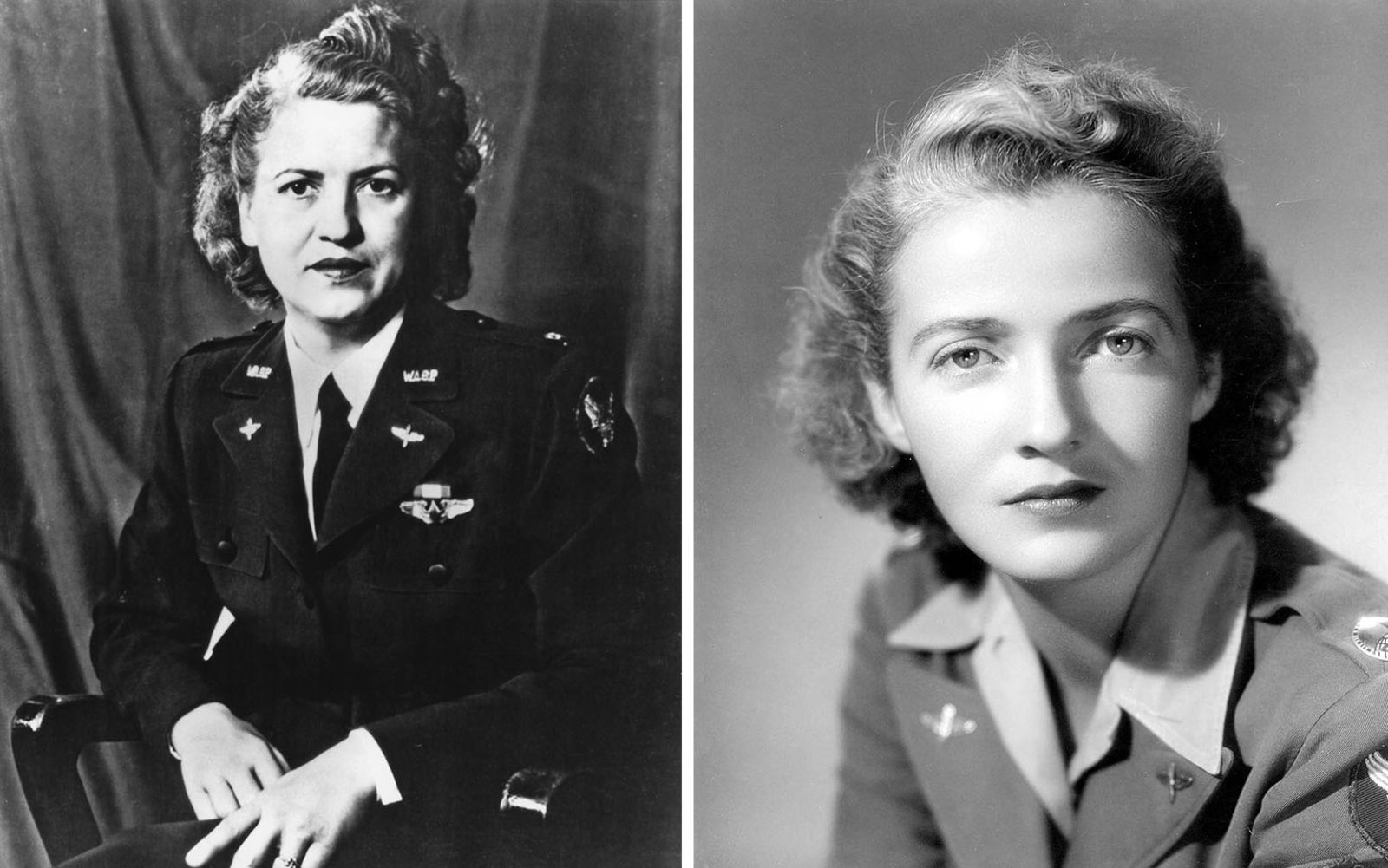

Before the war, pioneering aviators Jacqueline “Jackie” Cochran and Nancy Harkness Love each submitted a proposal to the Army to train women pilots to ferry aircraft from the factories where they were produced to their assigned bases, or to points of embarkation for shipment overseas. They argued that every woman who flew an airplane stateside would free up a male pilot for combat flying in Europe or the Pacific. Despite the lobbying efforts of First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, their requests were denied. Undaunted, Cochran traveled to England where she joined the British Air Transport Auxiliary and became one of the first American women to fly a military aircraft. In 1942, Love oversaw the creation of the Women’s Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron (WAFS), which began by ferrying US Army Air Forces trainers and light aircraft, but eventually transitioned to fighters, bombers, and large transports. Cochran returned to the US as the WAFS started flying and, with approval from General Henry “Hap” Arnold, she oversaw the formation of the Women’s Flying Training Detachment (WFTD) in the summer of 1942. The two groups worked independently and well until they were merged into the Women Airforce Service Pilots in 1943 under the direction of Cochran to codify training and operational standards. Though more than 25,000 women applied for the program, only 1,074 earned their wings. Primary training took place at Avenger Field in Sweetwater, Texas, and graduates not only ferried aircraft but also carried out test flights and towed targets for gunnery practice.

However, while women were doing the same work as their male military pilots, the Army still resisted allowing them to become pilot officers. Cochran continued to put pressure on the Army Air Forces to grant the WASPs a commission into the USAAF, but Arnold refused. Finally, Cochran issued an ultimatum: give the WASPs a commission or disband the group. Faced with a glut of pilots and trainees, the Army chose to disband the unit in December 1944 rather than create women officers. At the time the WASPs were disbanded, they had delivered 12,650 aircraft around the country and suffered 38 fatalities due to accidents. Despite giving their lives in service to their country, the Army did not afford any military honors at the funeral of a fallen WASP pilot. The pilot’s body was shipped home at family expense, and the family was not allowed to drape the American flag on the coffin. After the war, WASP veterans were barred from the honor of burial at Arlington National Cemetery until legislation was signed by President Barack Obama in 2016 which reversed the policy.

Though the WASPs opened the door for women military pilots, 30 more years would pass before Barbara Allen Rainey earned her wings in 1974 and became the first woman commissioned as a pilot in the US armed forces. She served in the US Navy until she lost her life in a training accident in 1982. The US Air Force followed suit in 1978 when it accepted its first female pilot, but women were still officially barred from combat roles until 1993.

August 6, 1945 – The United States drops the Little Boy atomic bomb on the Japanese city of Hiroshima. With the American victory in the Battle of Midway in June 1942, the tide of battle in the Pacific turned decisively to the United States and its allies. The methodical island hopping campaign began, with Allied forces capturing strategic islands for the construction of air bases while bypassing large groups of entrenched Japanese soldiers on other islands and cutting off their flow of supplies. By August 1944, the capture of Guam, Saipan, and Tinian meant that the US now had bases close enough to begin flying Boeing B-29 Superfortresses on strategic bombing missions against the Japanese home island. But even the most modern bomber in the world could only be so accurate from high altitude, and with so much of the Japanese war production spread throughout the cities and into people’s homes, the bombing wasn’t terribly effective. Even after General Curtis LeMay changed tactics in 1943 to the firebombing of Japanese cities, which resulted in huge loss of life, Japan fought on. It appeared that an invasion of the island would be the only way to end the war.

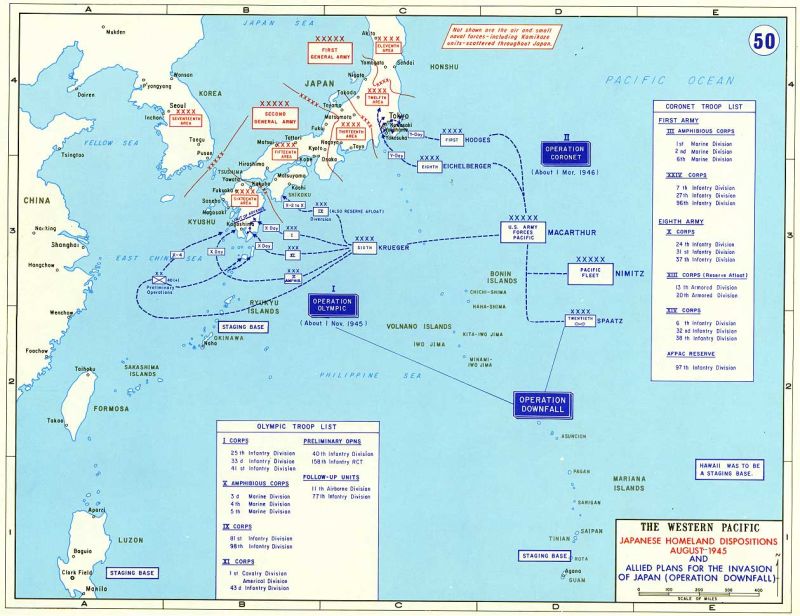

In the largest amphibious assault of WWII, the US secured the island of Okinawa on June 22, 1945 to serve as a launching point for the planned Operation Downfall, a two-part invasion of Japan that was slated to begin on November 1, 1945. American war planners knew that an invasion would be costly, with initial estimates predicting 130,000-220,000 Allied casualties. Once it became clear that the Japanese were preparing defenses at the intended landing sites, casualty estimates leapt to 1.7-4 million, with 400,000-800,000 dead. The US went so far as to produce a half million Purple Heart medals in preparation for the invasion. But would it be possible to end the war without an invasion? Could the Americans strike such a devastating blow that the Japanese would finally capitulate?

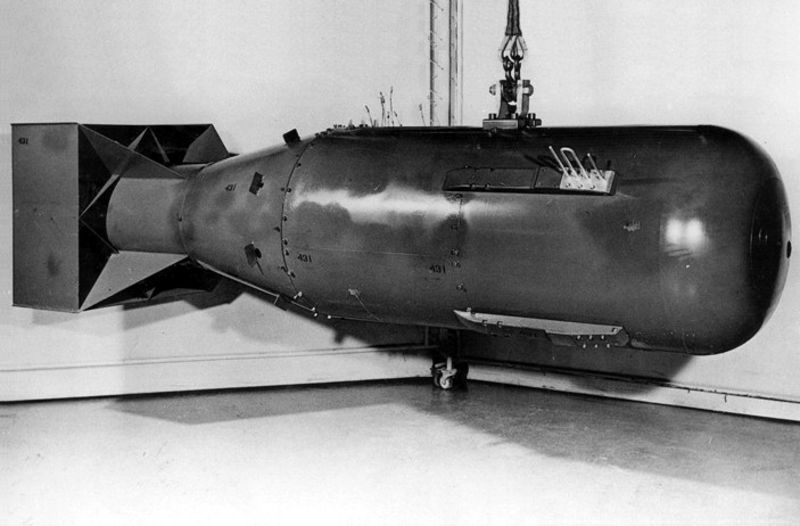

Development of a nuclear bomb in the US began before the war, when scientists who had fled Nazi Germany came to America with dire warnings of German advances in atomic science. In 1939, the Americans began working on their own bomb to counter the perceived German threat, with Berlin as a potential target. But work on the bomb progressed slowly, and the first successful test was not carried out until July 1945, after the war in Europe had ended. The organizational effort to create the group of pilots and planes that would drop the atomic bomb had begun the previous year with the formation of the 509th Composite Group under the command of Colonel Paul Tibbets at Wendover Army Air Field in Utah. The 509th flew the Silverplate B-29 Superfortress, which was structurally modified to carry the new bombs and was fitted with fuel injection, reversible pitch propellers, and special bomb bay doors that opened and closed quickly. To save weight and carry more fuel, all defensive armament was removed, along with all armor plating. The US now had a working bomb, and the means to carry it to Japan.

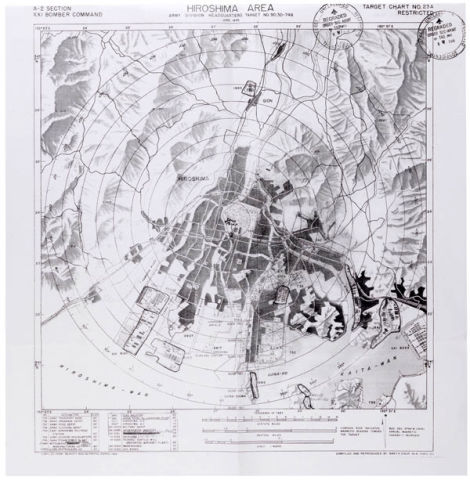

On July 26, 1945, the Allies issued the Potsdam Declaration which called for the unconditional surrender of Japan and threatened “prompt and utter destruction” if they did not comply. The Japanese, who had already shown their fanatical desire to fight to the death time and time again throughout the Pacific, rejected the Allies’ call for surrender. The US, faced with the inevitability of a costly invasion, decided to drop the atomic bomb on Japan. After considering numerous cities, Hiroshima was chosen as the first target because of its large military base, but also because the Americans wanted a target that was visible enough to have a psychological impact on the Japanese population.

Early in the morning of August 6, Tibbets and his crew departed Tinian in their Silverplate B-29, named Enola Gay after Tibbets’ mother, for the six-hour flight to Hiroshima. Over Iwo Jima, Enola Gay was joined by two other B-29s. The first was named Great Artiste and was loaded with instruments to measure the explosion. The second, an unnamed B-29, served as a photo ship. Thirty minutes from the target, mission commander Captain William Parsons armed the atomic bomb, codenamed Little Boy. Tibbets started the bombing run completely unopposed over the unsuspecting city, and released the bomb at 8:15 am (Hiroshima time). The massive explosion killed 70,000-80,000 people in the city, both soldiers and civilians, roughly 30% of the population. More than 70,000 were injured, and 4.7 square miles of the city were destroyed as massive fires engulfed the wooden buildings in the city. Those residents who survived the blast suffered horrifying burns, radiation sickness, and a host of other maladies.

The next day, President Harry S. Truman gave an address to the nation, and offered Japan a grave warning:

We are now prepared to obliterate more rapidly and completely every productive enterprise the Japanese have above ground in any city. We shall destroy their docks, their factories, and their communications. Let there be no mistake; we shall completely destroy Japan’s power to make war. . . . If they do not now accept our terms they may expect a rain of ruin from the air, the like of which has never been seen on this earth. Behind this air attack will follow sea and land forces in such numbers and power as they have not yet seen and with the fighting skill of which they are already well aware.

Despite Truman’s threat, and the suggestion that more nuclear attacks were on the way, the Japanese government remained silent, and did not surrender. So Truman made good on his word. Three days after the bombing of Hiroshima, a second atomic attack, this time on the city of Nagasaki, was carried out by a Silverplate B-29 nicknamed Bockscar. It was only after this second atomic bombing, which killed as many as 80,000 civilians, that the Japanese government finally agreed to an unconditional surrender on August 15, 1945, bringing an end to the Second World War.

Short Takeoff

August 6, 1996 – The first flight of the Kawasaki OH-1, a military scout and observation helicopter developed for the Japan Ground Self-Defense Force and the first helicopter entirely produced in Japan. Nicknamed Ninja, the OH-1 was created as a replacement for the Hughes OH-6 Cayuse light observation helicopter (LOH or “Loach”) and entered service in 2000. The OH-1 is powered by two Mitsubishi TS1 turboshaft engines which provide a maximum speed of 173 mph, and is fitted with an asymmetric Fenestron tail rotor that reduces noise and vibration. Development also included an attack variant that was rejected in favor of the Boeing AH-64 Apache.

August 6, 1945 – The death of Richard Bong, one of the United States’ most decorated fighter pilots and the highest-scoring American ace of WWII. Bong was born in Superior, Wisconsin on September 24, 1920 and received his wings in January 1942. During the war, Bong flew the Lockheed P-38 Lightning exclusively, and made the first of his 40 victories on December 27, 1942. For his service, Bong was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor in 1944 and was sent home to help sell war bonds. Following the war, Bong became a test pilot for Lockheed, but was killed when the fuel pump of his Lockheed P-80 Shooting Star malfunctioned during takeoff. Bong ejected, but was too close to the ground for his parachute to open fully.

August 7, 1990 – Operation Desert Shield begins. Following the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait on August 2, 1990, US President George HW Bush deployed US forces to Saudi Arabia to protect America’s strategic ally from further aggression by Iraqi President Saddam Hussein. Air assets of the US Air Force and US Navy teamed with aircraft from Saudi Arabia, Great Britain and France, and eventually formed a coalition of 48 nations resolved to oust Saddam from Kuwait. Five months of air operations to protect the buildup of 120,000 soldiers saw Operation Desert Shield become Operation Desert Storm, with the Coalition invasion to liberate Kuwait beginning on January 17, 1991 in what came to be known as the First Gulf War.

August 7, 1963 – The first flight of the Lockheed YF-12, a two-seat interceptor variant of the Lockheed A-12 reconnaissance aircraft. The YF-12 was developed in response to an Air Force requirement for an interceptor to replace the Convair F-106 Delta Dart that would be capable of speeds up to Mach 3. Following the cancelation of the North American XF-108 Rapier, Lockheed’s Kelly Johnson proposed version of the A-12 that would be fitted with the Hughes AN/ASG-18 fire control system and armed with Hughes AIM-47 Falcon missiles, specially modified to be fired by the YF-12 from internal missile bays. The Air Force ordered three prototypes and, during flight testing, the YF-12 set speed and altitude records for an interceptor of 2,070 mph and 80,257 feet. The YF-12 program was canceled in 1968, though the prototypes served as NASA test aircraft until 1979.

August 7, 1951 – The first flight of the McDonnell F3H (F-3) Demon, a single-seat fighter and interceptor developed for the US Navy as the successor to the McDonnell F2H Banshee. Unlike other fighters that were swept-wing variants of earlier sraight-winged aircraft, the Banshee was designed from the start with swept wings in an effort to counter Soviet fighter aircraft, though it was not capable of supersonic flight. Problems with engines plagued the Demon throughout its service life, and it was retired before it could serve in the Vietnam War. Despite difficulties with the Demon’s development, it ultimately served as the basis for the design of the McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom II, which replaced the Demon in Navy service.

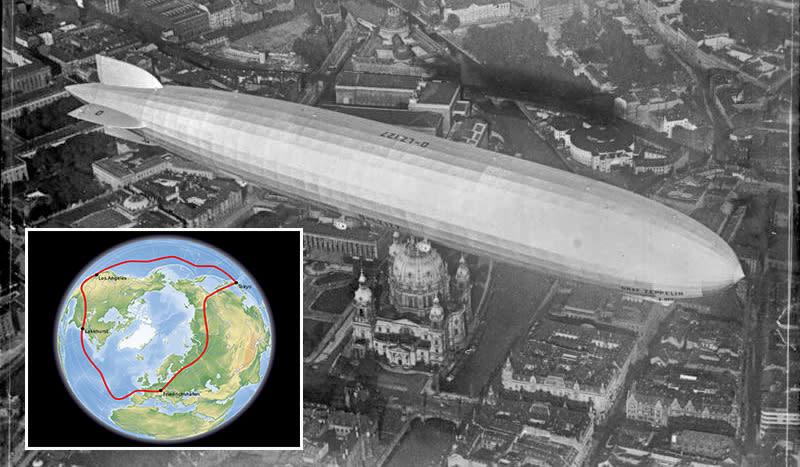

August 7, 1929 – The Graf Zeppelin (LZ-127) begins the first circumnavigation of the world by air. Before the arrival of ocean-spanning airliners in the 1930s, Zeppelins were the primary means of intercontinental air travel. Graf Zeppelin took its maiden flight on September 18, 1928, and completed its first flight to the United States the following month. At the urging of US newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst, the Graf Zeppelin began its eastward flight around the world by leaving Lakehurst, New Jersey and flying for Friedrichshafen in Germany before heading across the Soviet Union, Siberia, Japan, and then across the Pacific Ocean and back to New Jersey. The circumnavigation took 12 days to complete and covered 21,000 miles. On board was Hearst reporter Lady Grace Drummond-Hay who became the first woman to travel around the world.

August 7, 1928 – The first fight of the Curtiss Robin. Following the end of WWI, aviation transitioned from a purely military undertaking into the civilian sector, and designers sought to supply simple, relatively low-cost aircraft for the flying public. Making use of surplus Curtiss OX-5 90hp engines, Curtiss designed a high-wing monoplane with a wooden wing and tube frame fuselage that had room for a single pilot and two passengers. By the time production ended, Curtiss had built 769 Robins, and they served in almost every conceivable function, from personal use to carrying airmail to serving as a small airliner to carrying cargo. It also served as a platform for daredevils, including Dale “Red” Jackson, who performed over four hundred slow rolls without stopping in 1929. Later, Jackon teamed with Forrest O’Brine and set an endurance record by flying a Robin nonstop for 27 days. Douglas “Wrong Way” Corrigan also piloted a Robin on what he claimed was an accidental flight from New York to Ireland in 1938.

Connecting Flights

If you enjoy these Aviation History posts, please let me know in the comments. You can find more posts about aviation history, aviators, and aviation oddities at Wingspan.