Welcome to This Date in Aviation History, getting of you caught up on milestones, important historical events and people in aviation from September 2 through September 4.

September 2, 1937 – The first flight of the Grumman F4F Wildcat. The Grumman Corporation has a rich history of building rugged fighter aircraft for the US Navy, a tradition that can be traced all the way back to the days before WWII. Their penchant for making reliable aircraft that could take a pounding and still bring their pilots home earned the company the nickname “Iron Works,” and one of the first aircraft to truly live up to that name was the F4F Wildcat, the first in a long line of Grumman Cats.

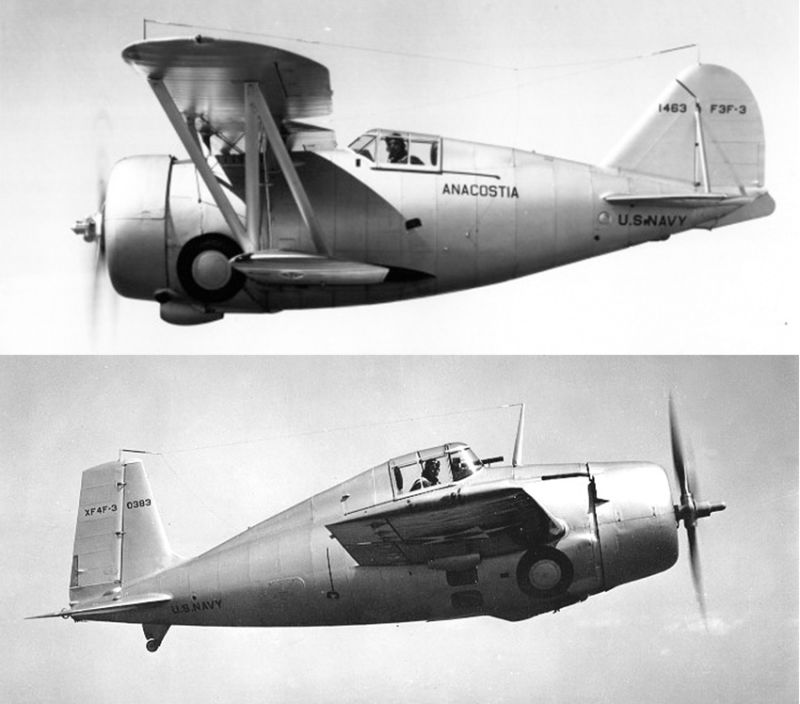

The Wildcat traces its lineage back to the first biplane fighter that Grumman produced for the Navy, the FF, which was notable for being the first carrier-based fighter to feature a retractable landing gear. Grumman continually developed their tubby fighter, first with the F2F, then the F3F. Though both of those iterations were biplane fighters, the classic F4F high-backed fuselage began to take shape. Even as the F3F was undergoing flight testing, Grumman was looking ahead to their next fighter, which was planned as another biplane. But by that time the Navy had made the decision to adopt a monoplane fighter in the Brewster F2A Buffalo. Still, the Navy placed an order for Grumman’s newest biplane, the G-16, in case the Buffalo didn’t fulfill their needs. The G-16, soon to be called the XF4F-1, turned out to be inferior to the Buffalo, so Grumman went back to the drawing board and redesigned their new fighter as a monoplane with improved wings and tail. They also beefed up the power with a supercharged Pratt & Whitney R-1830 Twin Wasp radial engine. This aircraft was known as the XF4F-3, and the classic Wildcat was born.

Both the US Navy and France placed orders for the new fighter but, when France fell to Germany in 1940, those aircraft were sent to England. There they were initially known as the Martlet, and what was to become the iconic US Navy fighter of the early Pacific War actually saw its first combat with the Royal Navy’s Fleet Air Arm. When war broke out in the Pacific in 1941, the Buffalo, which had been chosen over the Wildcat, proved to be nearly useless against modern Japanese fighters, and it was quickly withdrawn in favor of the Wildcat. Though the Wildcat was also no match for the Japanese Mitsubishi A6M Zero head-to-head, it was still better than the woefully underperforming Buffalo. The Wildcat’s strong construction, armored cockpit, and self-sealing fuel tanks allowed it to absorb punishment from Japanese fighters and stay in the fight while bringing its pilots home. Special tactics such as the Thach Weave helped keep the Wildcat effective until the more powerful Grumman F6F Hellcat arrived in the Pacific in 1943.

By the end of the war, and despite the Zero’s greater maneuverability, better climb rate, longer range, and effective tactics, the Wildcat—and her well-trained pilots—enjoyed an almost 7:1 kill ratio over the enemy. The Wildcat served the Navy and Marine Corps throughout the war and, with the arrival of the larger Hellcat, Wildcat operations were shifted to smaller escort carriers, with Wildcat pilots providing air cover for amphibious assaults. By the end of production in 1945, nearly 8,000 Wildcats had been built, and it was retired at the end of the war.

September 4, 1949 – The first flight of the Bristol Brabazon. History tends to remember the great planes, the ones that broke records, helped win wars, or made the world a smaller place. But oftentimes, aircraft that failed to enter widespread production are as fascinating as those that do. Planes like the Hughes H-4 Hercules, better known as the Spruce Goose, may not have been commercially viable, but their story is one that is worth telling, an tale of thinking on a grand scale that was every bit as impressive as it was impractical.

During WWII, the British government entered into an agreement with the United States whereby England would focus their efforts on the development of bombers and other military aircraft while the US provided them with transport aircraft. By the middle of the war, and looking to the future, the British government faced the unfortunate situation of having no significant transport aircraft under development to fly passengers after the war. In fact, many of the first postwar British airliners were converted bombers such as the Avro Lancastrian, which was developed from the Avro Lancaster strategic bomber.

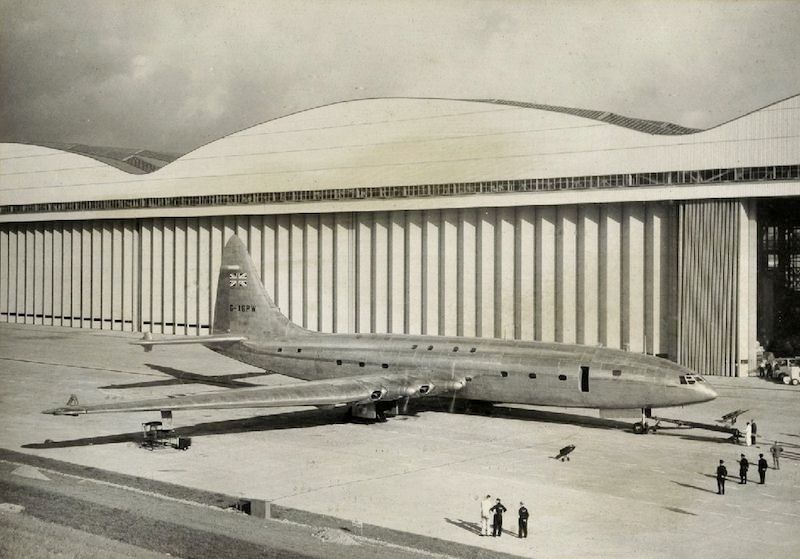

In 1943, the Brabazon Committee, led by John Moore-Brabazon, 1st Baron Brabazon of Tara, was assembled to address the vacuum in British aircraft design left by the absence of passenger aircraft development. The committee set to work identifying and categorizing England’s postwar aviation needs, and the report filed by the committee settled on four different aircraft types that would feature different levels of range, capacity, and propulsion. Type I called for a large, transatlantic airliner intended to serve the routes between London and New York, a 12-hour flight at the time. Bristol had already been working on what was called a “100 ton bomber,” one that found its closest parallel in the American Consolidated B-36 Peacemaker. However, development was halted when such a large bomber was deemed unnecessary. So when the call came for a large airliner, Bristol returned to the huge bomber and instead developed it into the Brabazon.

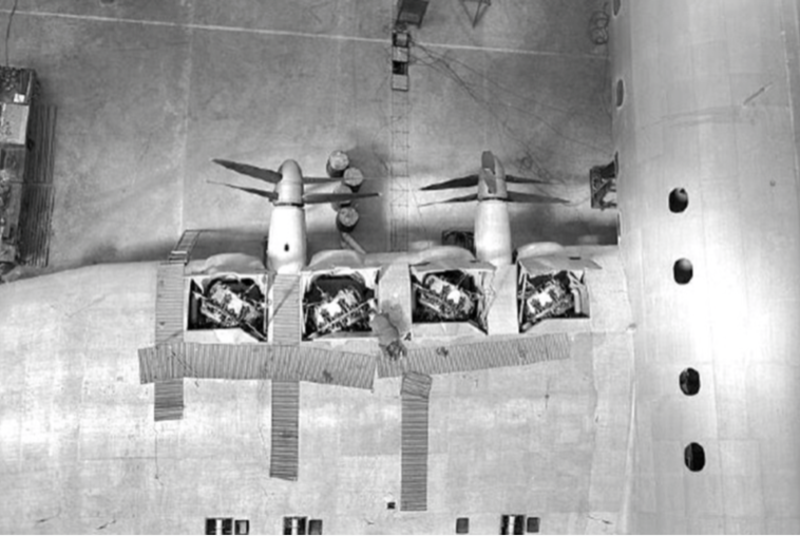

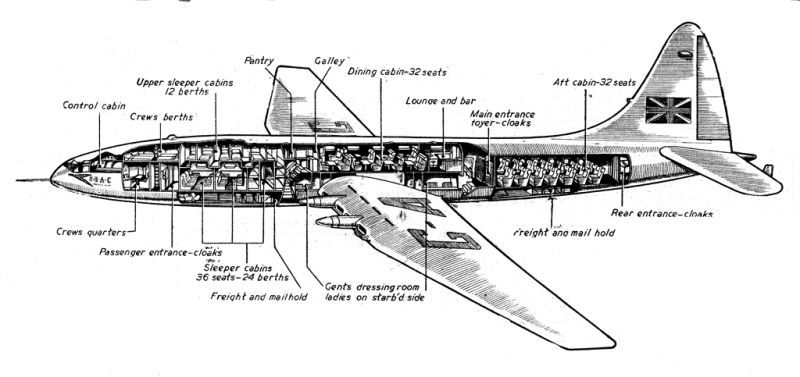

To pull such a large aircraft through the sky, the Brabazon featured four sets of contra-rotating propellers. But where many aircraft of this design used one engine to turn both propellers, the Brabazon used two, one for each prop. The Brabazon was powered by a total of eight Bristol Centaurus 18-cylinder engines, each providing over 3,000 horsepower to one prop. Cruising speed was 250 mph, with a range of 5,500 miles flying at 25,000 feet. The Brabazon was an enormous aircraft, almost as large as a modern Boeing 767, and its size would lead one to believe it could carry hundreds of passengers. However, the Brabazon only accommodated 100 passengers. Instead of row upon row of seats, it had sleeping berths, a galley, a 32-seat dining cabin, and a lounge with a bar. Bristol hoped that such an arrangement would appeal to big money travelers who could afford such accommodations. But carrying so few passengers in such grand style hearkened back more to transcontinental train travel than transatlantic passenger flight, and the arrangement was not appropriate for the burgeoning passenger market, where making money meant carrying as many passengers as possible.

One protoype was constructed, but the airlines had no stomach for such a large, expensive airplane that carried so few passengers. After millions of pounds were spent in development, the Brabazon was canceled in 1953. Though the Brabazon itself was deemed a failure, Bristol benefited from what it learned building the huge airliner, knowledge that they put to use developing the more traditional (and much more successful) Bristol Britannia. And the British aviation industry as a whole benefited from the increase in manufacturing infrastructure and techonological development that went along with the Brabazon and the rest of the work of the Brabazon Committee. Following its cancellation, the single Brabazon was broken up for scrap in 1953, along with the second uncompleted prototype, which would have been powered by turboprop engines. The Brabazon, despite its size, was relegated to relative obscurity.

Short Takeoff

September 2, 1998 – The first flight of the Boeing 717, a twin-engine, narrow-body commercial airliner first developed by McDonnell Douglas as the MD-95, the final variant of the venerable Douglas DC-9 line. Following the merger of McDonnell Douglas and Boeing in 1997, the MD-95 was rebranded as the Boeing 717, though Boeing had already used 717 as the internal designation of the military version of the Boeing 367-80 that entered service as the C-135 Stratolifter and KC-135 Stratotanker. The 717 entered service in 1999 with AirTran Airways (formerly ValuJet Airlines) as a medium-range airliner for the 100-seat market. When production ended in 2006, a total of 156 had been produced.

September 2, 1949 – The first flight of the de Havilland Venom, a single-seat turbojet-powered fighter-bomber developed from the de Havilland Vampire. The twin-tail boom configuration allowed for a shorter tailpipe behind the engine that took advantage of as much power as the early de Havilland Ghost turbojet could offer. Like the Vampire, the Venom was still built from a composite of wood and metal, but a thinner wing allowed greater speeds, while wingtip fuel tanks increased range. The Venom was introduced in 1952 and was the first British fighter to be fitted with an ejection seat. The Venom served the RAF until 1962, and with the Swiss Air Force until 1983.

September 2, 1942 – The first flight of the Hawker Tempest, an improved version of the Hawker Typhoon fighter-bomber. The Tempest benefited from a more powerful engine and a new laminar flow wing to become a formidable attack aircraft. The Tempest was one of the most powerful fighters of the war, and possessed particularly good low-level performance. It was powered by a single Napier Sabre liquid-cooled 24-cylinder engine that developed around 3,000 hp, had a top speed of 432 mph, and was armed with four 20mm Mark II Hispano cannons and up to 1,000 pounds of bombs or rockets. Introduced in January 1944, just over 1,700 Tempests were produced, and it was retired following the war.

September 2, 1925 – The crash of the rigid airship USS Shenandoah, the first of four rigid airships purchased by the US Navy. Shenandoah (ZR-1) was based on the German Zeppelin LZ 96 and was the first airship to be filled with helium rather than more flammable hydrogen. The airship took its maiden flight on September 4, 1923 and performed the first transcontinental flight in July 1924. On September 2, 1925, Shenandoah set out from Lakehurst, New Jersey for a promotional flight across the Midwest. While flying through a line of thunderstorms over Ohio, the airship was lifted by a violent updraft above the pressure limits of its gas bags and broke apart. Fourteen members of the 29-man crew were killed. Thousands of Ohioans came to view the crash site, and widespread looting of the hulk took place, with critical instruments stolen that could have helped with the investigation into the accident. Nevertheless, the crash led to changes in operating procedures, better weather forecasting, and the strengthening of future airships.

September 2, 1910 – Blanche Stuart Scott makes the first solo airplane flight by a woman in the United States. An adventurer at heart, Scott was the second woman to drive an automobile across the United States, and her notoriety led to an offer of flying lessons from American aviation pioneer Glenn Curtiss. Scott went on to become a professional pilot and made her debut with the Curtiss exhibition team as the first woman to fly at a public event, earning her the nickname “Tomboy of the Air.” After gaining fame as a stunt pilot, Scott was the first American woman to make a long-distance flight of 60 miles, and also became a test pilot for Glenn Martin. She retired from flying in 1916 because she was upset by an American public that seemed obsessed with air crashes rather than flying achievements, as well as the lack of opportunity for women pilots.

September 3, 2017 – Astronaut Peggy Whitson returns to Earth after setting an endurance record for American astronauts. Whitson made her first trip to the International Space Station (ISS) in 2002 and stayed for 184 days, then returned in 2008 for a 191-day stay. On her third trip she spent 289 days in space. With the culmination of her third long-duration mission aboard the ISS, Whitson ran her total number of days spent in space to 665, breaking astronaut Jeff Williams’ previous record of 534 days of total time in space. Whitson is the world’s oldest spacewoman when she flew at age 57, and the first to command the ISS twice. She has spent more then 53 hours performing spacewalks, the most of any female astronaut. In 2009, Whitson became the first woman to be appointed chief of the astronaut office, a position she held until 2012. While Whitson’s record is for accumulated days in space, the record for the longest single stay in orbit belongs to cosmonaut Valeri Polyakov, who spent 437 days on the Russian space station Mir.

September 3, 1982 – The first flight of the Beechcraft 1900, a 19-passenger twin-turboprop regional airliner and one of the most popular small airliners ever produced. The 1900 was developed from the Beechcraft Super King Air and was designed with all-weather flight capabilities, as well as the ability to operate from short runways. Power comes from a pair of Pratt & Whitney Canada PT6 turboprops which give the 1900 a top speed of 518 mph. When production ended in 2002, Beechcraft had built nearly 700 aircraft, and it remains in service with over 80 civilian operators and numerous military operators, including the US Air Force, where it is known as the C-12J.

September 3, 1981 – The first flight of the British Aerospace 146, a short-haul regional airliner manufactured from 1978-2001 by British Aerospace. The 146 is powered by four Textron Lycoming ALF 502 turbofan engines mounted on pods under a high cantilever wing and can accommodate up to 112 passengers depending on configuration. The 146 entered service in 1983 and became very popular at city airports, where it took advantage of its short-field performance and relatively quiet operation. Nearly 400 copies of the 146 were produced, and it continues to serve worldwide as an airliner and cargo aircraft, including some that have been converted for aerial firefighting duties.

September 3, 1948 – The loss of Silverplate Boeing B-29 Superfortress The Great Artiste. The two Silverplate Boeing B-29 Superfortresses that dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the Enola Gay and Bockscar, are well known to history. But they weren’t the only aircraft of that type to make those historic flights. On each mission, the bombers were accompanied by two other Silverplate B-29s, one with photographers and the other with measuring instruments. The Great Artiste (44-27353) was the only B-29 to fly on both atomic missions. Built at the Glenn L. Martin Plant, The Great Artiste flew conventional bombing missions before the nuclear raids of August 1945, but during a polar navigation training mission after the war it developed engine trouble after takeoff from Goose Bay, Labrador, overran the runway on landing and was seriously damaged. Despite its historical significance, The Great Artiste was scrapped in 1949.

September 4, 1957 – The first flight of the Lockheed JetStar, the first dedicated business jet to enter service and, with accommodations for up to ten passengers, the largest in its class at the time. Unlike most bizjets of the era, the JetStar had four engines rather than two, and was originally powered by four Pratt & Whitney JT12 turbojets. Later production aircraft received quieter, more fuel-efficient Garrett TFE731 turbofan engines that gave it a top speed of 547 mph. Not only did it serve as Kelly Johnson’s personal jet, the JetStar entered US military service as the C-140 and also served as President Lyndon Johnson’spersonal aircraft, which he nicknamed Air Force One-Half. Just over 200 were produced from 1957-1978.

September 4, 1936 – Louise Thaden becomes the first woman to win the prestigious coast-to-coast Bendix Trophy Race. At a time when aviation was dominated by male pilots, Louise Thaden shocked the world when she and her copilot Blanche Noyes won the Bendix transcontinental race. The pair set a new world record time of 14 hours 55 minutes flying a Beech C17R Staggerwing. But that was only the first of Thaden’s accomplishments. She set a altitude record of 20,260 feet for woman pilots in 1928, an endurance record of over 22 hours in 1929, teamed up aviatrix Frances Marsalis to set a record time of 196 hours in the air, and was a founding member of the Ninety-Nines organization for woman pilots. Though she retired from racing in 1938, Thaden served with the Civil Air Patrol during WWII, and died in 1979.

September 4, 1933 – The death of Florence Gunderson Klingensmith, an American aviatrix active during the Golden Age of Aviation and one of the first to participate in air races against male pilots. Klingensmith became interested in aviation after Charles Lindbergh visited her hometown of Fargo, North Dakota, and she began her flying career as a performing skydiver in exchange for flying lessons. She acquired her first airplane by going door to door to solicit funds, and she set a world record in 1931 by completing 1,078 loops in succession. Taking up air racing, Klingensmith was the first woman to enter the Frank Phillips Trophy Race in 1933 flying a Gee Bee Model Y Senior Sportster. While flying in fourth place at over 200 mph, the airplane began to disintegrate, and Klingensmith was killed while attempting to bail out. Her death led to a ban on women participating in air races. Klingensmith was 29 years old.

Connecting Flights

If you enjoy these Aviation History posts, please let me know in the comments. You can find more posts about aviation history, aviators, and aviation oddities at Wingspan.