Welcome to This Date in Aviation History, getting of you caught up on milestones, important historical events and people in aviation from November 11 through November 13.

November 11, 1956 – The first flight of the Convair B-58 Hustler. The Nuclear Age dawned on August 6, 1945 when the United States dropped the first atomic bomb on the Japanese city of Hiroshima, followed by a second bomb three days later on the city of Nagasaki. Fortunately for the world, no other nuclear bombs have ever been dropped in anger, but development of nuclear-capable bombers continued after the war, and the problem facing the US Air Force was how best to deliver a nuclear weapon deep into enemy territory, specifically the Soviet Union. In the era before the intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) and the surface-to-air missile (SAM), conventional wisdom held that the only way to successfully complete a nuclear bombing mission was to fly at high altitude above enemy fighters and at the greatest possible speed.

In 1949, the Air Research and Development Command (ARDC) issued a Generalized Bomber Study for which numerous aircraft manufacturers submitted proposals to build a new jet-powered bomber for the Strategic Air Command. The Air Force chose Boeing and Convair to proceed. Boeing proposed their XB-59 supersonic medium bomber, while Convair proposed an aircraft known as the MX-1964. In 1952, the Air Force selected Convair as the winner, and the new bomber received the designation XB-58.

Based on experience with their XF-92 interceptor prototype, Convair’s offering was a fully delta wing aircraft and was powered by four General Electric J79 axial flow afterburning turbojets each housed in a long slender pod beneath the wings. The Hustler was capable of carrying five nuclear weapons, with four of them carried on external pylons under the wings and a fifth housed in a large pod under the fuselage that also contained fuel. The Hustler had no internal bomb bay.

To keep the fuselage as slender as possible, the B-58's three-man crew was seated one behind the other, and later models featured a clamshell-like ejection capsule that also included the control stick, meaning that the pilot could continue to fly the plane even when “turtled up,” ready for ejection at a moment’s notice. The escape system could safely eject the crew at 70,000 feet and at speeds as high as Mach 2, and the ejection capsule could also double as a life raft.

The choice of Hustler for the B-58's nickname turned out to be an apt moniker, as the B-58 was the first supersonic jet bomber and could fly as fast as Mach 2. Depending on the payload, the Hustler could climb at nearly 46,000 feet per minute with a light load, and it set 19 world speed records during its career, including a transcontinental flight of just over two hours. But as fast as the Hustler was, it was expensive to produce and, when compared to the much larger Boeing B-52 Stratofortress, the B-58 carried a relatively light bomb load and had a shorter range. Following the introduction of Soviet SAMs, the Hustler’s mission changed to low-level penetration which further limited its range. And the fact that it was designed exclusively as a nuclear bomber meant that it could not carry conventional weapons, further limiting its mission capability. After a relative brief 10-year career, the Hustler was retired in favor of the General Dynamics FB-111A, which could match the B-58 in speed and could carry a far more flexible weapons load, including nuclear bombs. The Hustler was retired in January 1970 and, of the 116 Hustlers produced, eight survive today as display aircraft.

November 12, 2001 – The crash of American Airlines Flight 587. In the Hollywood blockbuster movie Top Gun, an accident claims the life of Goose, Maverick’s best friend and Radar Intercept Officer, when their F-14 flies through the “jet wash” of the fighter ahead of them. In the unstable air, Maverick loses control and the Tomcat goes into a flat spin. The pair ejects, but Goose is killed. The story was written by Hollywood, but the scenario is very real. However, the phenomenon that caused Maverick to lose control is actually called wake turbulence, because jet engines have nothing to do with creating the turbulent air. By the 196os, aerodynamicists finally understood that it wasn’t the air coming out of the jet engines that caused turbulence, it was the wingtip vortices. These horizontal tornadoes of air generated by the wings of an aircraft can wreak havoc on those airplanes following behind, and all pilots are trained to deal with wake turbulence. Air traffic controllers routinely advise aircraft during landing or takeoff to be aware of wake turbulence from aircraft in the pattern ahead. Crashes caused by wake turbulence are rare, but perhaps the best known, and most tragic, was the crash of American Airlines Flight 587.

AA587 was a regularly scheduled flight from New York’s John F. Kennedy International Airport to the Dominican Republic. Shortly after takeoff, the Airbus A300 (N14053) flew into the wake turbulence left behind by a Japan Air Lines Boeing 747. In an effort to maintain control, the first officer initiated a series of hard, complete deflections of the rudder. These actions, lasting approximately 20 seconds, placed twice the amount of stress on the vertical stabilizer than Airbus had designed it for, and caused the entire stabilizer to break away from the fuselage. Without the yaw control from the stabilizer, the airliner entered a flat spin, and the stresses on the airframe caused both engines to shear off the wings. The airliner came down in a Queens, New York neighborhood, killing all 260 passengers and crew plus five people on the ground. It was the second deadliest crash in New York state history, and the second deadliest accident involving an A300.

Coming just two months after the September 11 terrorist attacks on New York City and Washington, DC, immediate speculation focused on another act of terrorism. However, National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) investigators quickly ruled that out, and focused instead on the joint where the composite tail structure attached to the aluminum fuselage. They found that the titanium bolts and composite lugs were sufficiently strong, so attention turned to the first officer’s rudder deflections as the likely cause of the stabilizer separation. American Airlines blamed Airbus for making the rudder pedals too sensitive, and Airbus blamed American for faulty pilot training, saying that its pilots were trained to handle wake turbulence in an overly aggressive fashion. Ultimately, the NTSB investigation determined that, while both parties shared some responsibility, it was the first officer’s “unnecessary and excessive rudder pedal inputs” that caused the structural failure leading to the crash. In light of those findings, American Airlines modified its wake turbulence training program.

November 12, 1952 – The first flight of the Tupolev Tu-95. At the close of WWII, the best bomber the Soviet Union had in their arsenal was the Tupolev Tu-4 (NATO reporting name Bull), a down-to-the-last-rivet copy of a captured American Boeing B-29 Superfortress. The Tu-4 was a fine bomber (after all, it was a clone of the B-29), and the Soviets built nearly 850 of them. But what the Soviet Air Forces lacked was a truly intercontinental bomber that could make a round trip attack on the United States. Tupolev first addressed this deficiency with the Tu-85 (NATO reporting name Barge), the ultimate development of the Tu-4, and the significantly larger and heavier Tu-85 had an unrefueled range of nearly 7,500 miles. But the Tu-85, powered by massive compound radial engines, was an anachronism in an era when jets and turboprops were becoming the engines of choice, and only two were ever built. Additionally, American experience with the B-29 in the Korean War showed that piston-powered bombers were vulnerable to the new breed of jet fighters.

The Myasishchev Design Bureau began work on the M-4 (NATO reporting name Bison), but its four thirsty turbojet engines limited its range and it was never able to fulfill the transoceanic bombing mission. Tupolev, however, had begun work on a turboprop-powered bomber, similar in many ways to the Boeing Model 464, an early design concept that eventually led to the jet-powered B-52 Stratofortress.

Designated Tu-95 (NATO reporting name Bear), the bomber’s 35-degree swept wing housed four massive Kusnetsov NK-12 turboprops, the most powerful turboprops ever built. Each provided 14,800 shaft horsepower and turned enormous 18-foot diameter contra-rotating propellers whose tips moved at supersonic speeds. The resulting noise made the Tu-95 one of the loudest aircraft ever built, but all that noise also made for a very fast bomber. When the Americans first encountered the Bear, they were chagrined to find that the Tu-95's top speed of 575 mph was faster than the early straight-winged fighters in service over Korea.

The Tu-95 entered service in 1955, and immediately caused great consternation in the West. Not only was it faster than many fighters of its day, its 9,400-mile range put it easily within reach of North America. It was also capable of delivering the RDS-220 hydrogen bomb, nicknamed the Tsar Bomba, the most powerful nuclear weapon ever detonated. Future variants were armed with air-to-ground missiles such as the Raduga Kh-20 nuclear cruise missile, the Kh-22 anti-ship missile designed to destroy American aircraft carriers, or up to eight Kh-101/102 cruise missiles housed on underwing pylons. Reconnaissance variants became a common sight along the Pacific Ocean borders of the United States and Canada, where the Soviets tested the reaction of NORAD air defenses. Bears were also a constant shadow to US and NATO fleets the world over.

Over 500 Tu-95s were built from 1952-1993, and even in an age of supersonic intercontinental jet bombers, the turboprop Tu-95 remains in service with the Russian Air Force. The original Bear was subsequently developed into the Tu-142 maritime patrol and anti-submarine warfare variant, as well as Tupolev Tu-114 Rossiya civilian airliner, which set no less than five world records for speed and range, some of which weren’t surpassed until the arrival of the Boeing 747SP. The Rossiya remains the fastest propeller-powered airliner in history, a record it has held since 1960.

Short Takeoff

November 11, 1983 – The first flight of the CASA/IPTN CN-235, a medium-range transport and cargo aircraft developed as a joint venture between Spain and Indonesia. Powered by two General Electric T700 turboprop engines, the CN-235 was originally designed for the military for use in maritime patrol and surveillance, but it also serves as a civilian regional airliner. Turkey is the largest international operator of the CN-235, flying 50 examples, along with the militaries of 25 other nations. The US Air Force operates a small number for use with special forces, and it is also flown by the US Coast Guard as the HC-144 Ocean Sentry.

November 11, 1946 – The first flight of the Sud-Ouest Triton, the first jet-powered aircraft to be built in France. Development of the Triton by SNCASO (Société nationale des constructions aéronautiques du sud-ouest), which later became known as Sud Aviation, began in 1943 as a clandestine program hidden from the Germans who had occupied France. The first Triton was powered by a Junkers Jumo 004 turbojet engine, and later aircraft received the Rolls-Royce Nene centrifugal compressor turbojet. Only five Tritons were produced before the project was abandoned. Note the air intake under the nose, which passed through the cockpit and between the pilots.

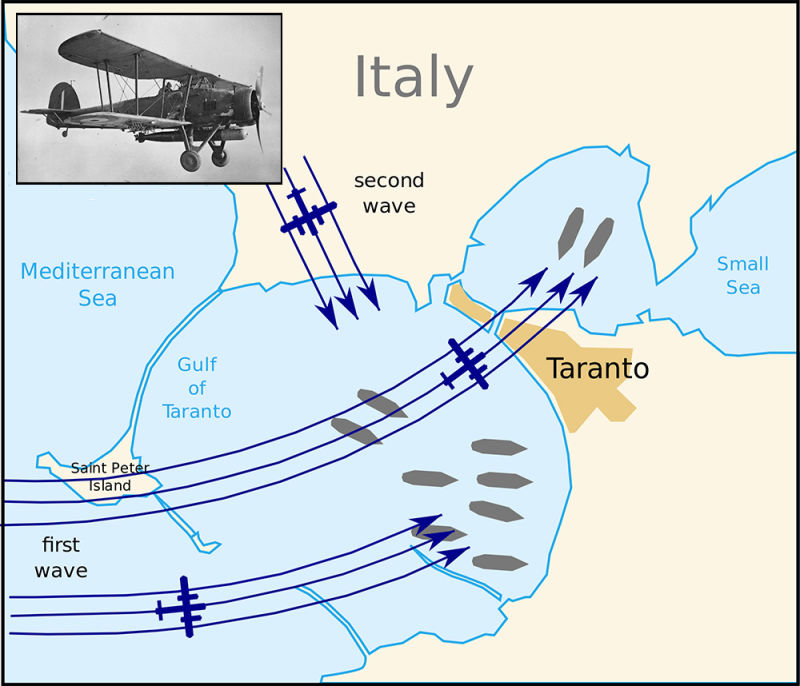

November 11-12, 1940 – The Battle of Taranto. The location of a powerful Italian fleet in the port of Taranto on the heel of Italy created significant problems for the British who sought to ply the Mediterranean Sea and supply its troops in North Africa. Plans to eliminate the fleet had been drawn up even before the war began, and a pause in Italian operations in North Africa afforded the opportunity for a British strike. In an audacious nighttime raid, a naval task force built around HMS Illustrious (87) attacked with obsolete Fairey Swordfish biplanes armed with either torpedoes or bombs and managed to sink one battleship and seriously damage two others. Three other ships were also damaged and 59 Italians were killed, against the loss of two British aircraft with two airmen killed and two captured. Though it was hoped that the Italian Navy would cease to be a force in the region, this was not the case. However, the attack was the first naval engagement carried out entirely by aircraft, and it signaled the ascendancy of the airplane over the battleship as the most powerful weapon for the future of naval warfare. It is also likely that the British attack heavily influenced the Japanese in their plans for a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor one year later.

November 11, 1918 – World War I ends. World War I was the first war in which 20th century technology came to the battlefield. The machine gun, which was believed to be so fearsome a weapon as to make war unthinkable, decimated armies as they tried to advance from trenches, and the tank made its first appearance on the battlefield in an attempt to break the stalemate of trench warfare. Beginning just 11 years after the Wright Brothers’ first flight, WWI also saw the first widespread use of aircraft in battle. At first, observation planes, known as scouts, reconnoitered enemy lines, and opposing pilots passed with a friendly wave. That soon gave way to small arms carried aloft, and eventually dedicated fighters and bombers. By the end of the Great War, the British, French, and Americans had suffered roughly 20,000 air crew casualties (killed, wounded, missing, or POW), while the German Air Service suffered over 15,000. The airplane had found its place as an indispensable part of modern warfare.

November 12, 1996 – A Saudi Arabian Airlines Boeing 747 collides in midair with a Kazakhstan Airlines Ilushin Il-76. Saudi Arabian Flight SVA763, a Boeing 747 (HZ-AIH), was flying from Delhi to Jeddah with a stop in Dhahran, while a chartered Kazakhstan Airlines Ilyuishiun Il-76 (UN-76435) was operating from Chimkent to Delhi. The 747 had taken off from Delhi, while the Il-76 was descending to land at Delhi and was ordered to hold at 15,000 feet. Both aircraft were on the same flightpath and under the direction of the same controller. However, the crew of the Kazakhstan Airlines plane descended below 15,000 and continued to drop, and when the controller called to warn him of the approaching 747 the planes had already collided. Both aircraft crashed shortly after the collision, killing all 312 passengers and crew on the 747 and all 37 on board the Ilyushin. It remains the world’s deadliest mid-air collision, and the worst accident to occur in India.

November 12, 1981 – The launch of Space Shuttle Columbia on STS-2, the second Space Shuttle mission, the second flight of Columbia. The mission marked the first time a spacecraft was reused and returned to orbit. It was also the first mission to utilize the robotic arm developed for the Shuttle by Canada. Officially called the Remote Manipulator System but popularly known as the Canadarm, the manipulator was used to maneuver payloads out of and into the Shuttle’s cargo bay. STS-2 was originally envisioned as a boost mission to push the Skylab space station into a higher orbit, but delays in the Shuttle program made that impossible, and Skylab fell to earth in 1979, two years before the the launch of STS-2.

November 12, 1932 – The first flight of the de Havilland Dragon. Building on the success of the single-engine de Havilland Fox Moth, de Havilland responded to a request by Hillman’s Airways for a larger, twin-engine design. Using the same engine and construction techniques of the Fox Moth, the Dragon had capacity for a pilot and 6 to 10 passengers, with a maximum speed of 128 mph. Though production had stopped before WWII, the Dragon re-entered production to serve as a navigational trainer for the Royal Australian Air Force. A total of 2,002 Dragons were built, and it was subsequently developed into the larger and more powerful de Havilland Dragon Rapide.

November 12, 1921 – The first air-to-air refueling is completed. While the 1923 aerial refueling via a long hose strung between two Airco DH.4 biplanes is considered the first official and even remotely practical aerial refueling of an airplane, a wing-walking daredevil named Wesley May laid claim to the actual first refueling when he strapped a five-gallon can of gas weighing approximately 40 pounds onto his back and climbed from a Lincoln Standard biplane in flight onto a Curtiss Jenny flying alongside. This stunt was clearly not meant to be a practical solution, but barnstorming was never about being practical.